Ursula K. Le Guin, “Vaster Than Empires and More Slow,” in Buffalo Gals and Other Animal Presences (New York: Plume, 1987), 97.

Ibid., 113.

Ibid., 118.

Ibid., 122.

Ibid., 127.

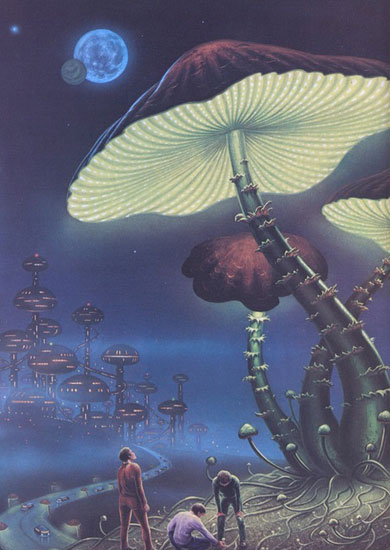

In the 1987 introduction to the story, Le Guin does not mention Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis explicitly but does refer to “Deo, Demeter, the grain-mother, and her daughter/self Kore the Maiden called Persephone” as ancient mythological paradigms for envisioning humans’ relationship to the plant world. See ibid, 83.

Ibid., 115.

For detailed analyses of this rhetoric, see Greg Garrard, Ecocriticism (London: Routledge, 2004), 85–107; Lawrence Buell, The Environmental Imagination: Thoreau, Nature Writing, and the Formation of American Culture (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1995), 280–308; Jimmie M. Killingsworth and Jacqueline S. Palmer, “Millennial Ecology: The Apocalyptic Narrative from Silent Spring to Global Warming,” in Green Culture: Environmental Rhetoric in Contemporary America, eds. Carl G. Herndl and Stuart C. Brown (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1996); and Frederick Buell, From Apocalypse to Way of Life: Environmental Crisis in the American Century (New York: Routledge, 2003), 177–208.

Rachel Carson, Silent Spring (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1962), 3.

Killingsworth and Palmer, “Millennial Ecology,” 41.

Edward Abbey, The Monkey Wrench Gang (New York: Perennial, 2000), 167, 172. Shell and IG Farben also figured prominently in Pynchon’s vision of corporate conspiracy in Gravity’s Rainbow, published only two years before The Monkey Wrench Gang.

Buell, From Apocalypse to Way of Life, 177–208.

For a more detailed summary of the debates about the notion of human and/or economic development that surround these terms, see Patrick Hayden, Cosmopolitan Global Politics (Hants, England: Ashgate, 2005), 121–51.

See T. V. Reed, “Toward an Environmental Justice Ecocriticism,” in The Environmental Justice Reader: Politics, Poetics, and Pedagogy, eds. Joni Adamson, Mei Mei Evans, and Rachel Stein (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2002), 151.

Julie Sze, “From Environmental Justice Literature to the Literature of Environmental Justice,” in The Environmental Justice Reader, 168.

Zygmunt Bauman, Postmodern Ethics (Oxford: Blackwell, 1993, 217–18.

Ibid., 219.

Arne Naess, “Identification as a Source of Deep Ecological NAttitudes,” in Deep Ecology, ed. Michael Tobias (San Diego: Avant Books, 1985), 268.

Naess, Ecology, Community and Lifestyle, trans. David Rothenberg (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 144.

Ibid.

Kirkpatrick Sale, Dwellers in the Land, 2nd ed. (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2000), 53.

This opposition to modernity as a general sociopolitical structure is also clearly articulated by some environmentalist thinkers who draw on more leftist traditions of thought. British philosopher Mick Smith argues that “radical environmentalism is engaged in a fundamental critique of modernism; its alternative culture challenges modern life to its very core.” (Smith, An Ethics of Place: Radical Ecology, Postmodernity, and Social Theory (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2001, 164–65). Yet in Smith’s thought, “place” is quite deliberately used as an ambiguous concept that sometimes refers to actual localities (as in his discussion of the British antiroads movement) and sometimes to a more general reliance on the concrete rather than on abstract categories.

Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 183–86.

Janet Biehl, “‘Ecology’ and the Modernization of Fascism in the German UltraRight,” in Society and Nature 1 (1993): 131–33; Janet Biehl and Peter Staudenmaier, Ecofascism: Lessons from the German Experience (Edinburgh: AK Press, 1995); Anna Bramwell, Blood and Soil: Richard Walther Darré and Hitler’s “Green Party” (Bourne End, Buckinghamshire, England: Kensal Press, 1985).

Arif Dirlik, “Place-Based Imagination: Globalism and the Politics of Place,” in Places and Politics in an Age of Globalization, eds. Roxann Prazniak and Arif Dirlik (Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 2001), 35–42; Timothy Brennan, At Home in the World: Cosmopolitanism Now (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1997), 44–65.

Fredric Jameson, “Notes on Globalization as a Philosophical Issue,” in The Cultures of Globalization, eds. Fredric Jameson and Masao Miyoshi (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1998), 74–75.

Dirlik, “Place-Based Imagination,” 23–24.

Le Guin, “Vaster Than Empires and More Slow,” 123.

Ibid., 127.

This text is an edited excerpt from the chapter “From the Blue Planet to Google Earth: Environmentalism, Ecocriticism, and the Imagination of the Global” in Ursula K. Heise, Sense of Place and Sense of Planet: The Environmental Imagination of the Global (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008). © the author and Oxford University Press.