See Quentin Meillassoux, Après la finitude. Essai sur la nécessité de la contingence (Paris: Seuil, 2006)

Miguel Carid, Yawanawa: da Guerra à Festa, MA dissertation, PPGAS / UFSC (1999), 166, quoted in Oscar Calavia, “El Rastro de los Pecaríes. Variaciones Mí́ticas, Variaciones Cosmológicas e Identidades É́tnicas en la Etnología Pano,” Journal de la Société des Americanistes 87: 161–76.

Orlando Calheiros, Aikewara: Esboços de uma Sociocosmologia Tupi-Guarani, PhD Thesis, PPGAS / Museu Nacional do Rio de Janeiro (2014), 41.

Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, “The crystal forest: notes on the ontology of Amazonian spirits,” Inner Asia 9 (2) (2007): 153–72.

With some improvement in the moral field, literal cannibalism, for instance, becomes objectively unnecessary, since, with the advent of the cosmological era, animals and plants adequate for human nourishment appear.

See Davi Kopenawa and Bruce Albert, La Chute du Ciel: Paroles d’un Chaman Yanomami (Paris: Plon, 2010); Bruce Albert, Temps du Sang, Temps des Cendres: Représentation de la Maladie, Système Rituel et Espace Politique chez les Yanomami du Sud-Est (Amazonie Brésilienne), PhD thesis (1985), Université de Paris X (Nanterre).

Gerald Weiss, “Campa Cosmology,” Ethnology 9 (2) (1972): 169–70. “Many, if not all categories”— compare this to the Aikewara exception concerning tortoises in the characterization of the pan-human state of pre-cosmological reality. These provisions are important because they highlight an essential dimension of Amerindian mythocosmologies: such expressions as “nothing,” “everything,” or “all” function as qualifiers (not to say “quasifiers”) more than as quantifiers. We cannot delve deeper into this discussion here, but it carries obvious implications as to the adequate comprehension of the indigenous concepts of cosmos and reality. Everything, including “the Everything,” is only imperfectly totalizable: the exception, the remainder, and the lacuna are (almost always) the rule.

Claude Lévi-Strauss, La Potière Jalouse (Paris: Plon, 1985), 190–92.

Edward Schieffelin, The Sorrow of the Lonely and the Burning of the Dancers (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1976), 94.

That statement requires nuancing and differentiating in regard to several Amerindian cosmologies, not to mention the occasional exception to it. There is an ongoing debate on the extension and comprehension of this mythophilosopheme regarding a primordial or infrastructural humankind in indigenous America, a debate that is tied with another one around the concepts of “animism” and “perspectivism,” which we will not explore here.

See Günther Anders, Le Temps de la Fin (Paris: L’Herne, 2007), 75: “the pre-human region whence we came is that of total animality.”

“Ethnographic present” is what anthropologists call, nowadays almost always with a critical intention (although Hastrup has raised an important objection to that), the discipline’s classic narrative style, which situates monographic descriptions in a timeless present more or less coetaneous with the observer’s fieldwork. This style pretends to ignore the historical changes (colonialism, etc.) that allowed precisely for ethnographic observation. We shall use the expression, however, in a sense doubly opposed to that, so as to designate the attitude of “societies against the state” in regard to historicity. The ethnographic present is therefore the time of Lévi-Strauss’s “cold societies,” societies against accelerationism, or slow societies (as one speaks of slow food or slow science—see Isabelle Stengers), for whom all cosmopolitical changes necessary for human existence have already taken place, and the task of ethnos is to secure and reproduce this “always already.” See Kirsten Hastrup, “The Ethnographic Present: A Reinvention,” Cultural Anthropology 5/1: 45–61; Isabelle Stengers, Une Autre Science Est Possible! Manifeste pour un Ralentissement des Sciences (Paris: La Découverte, 2013).

An Amazonian metaphysician could call this the argument of “human ancestrality” or “the evidence of the anthropofossil.”

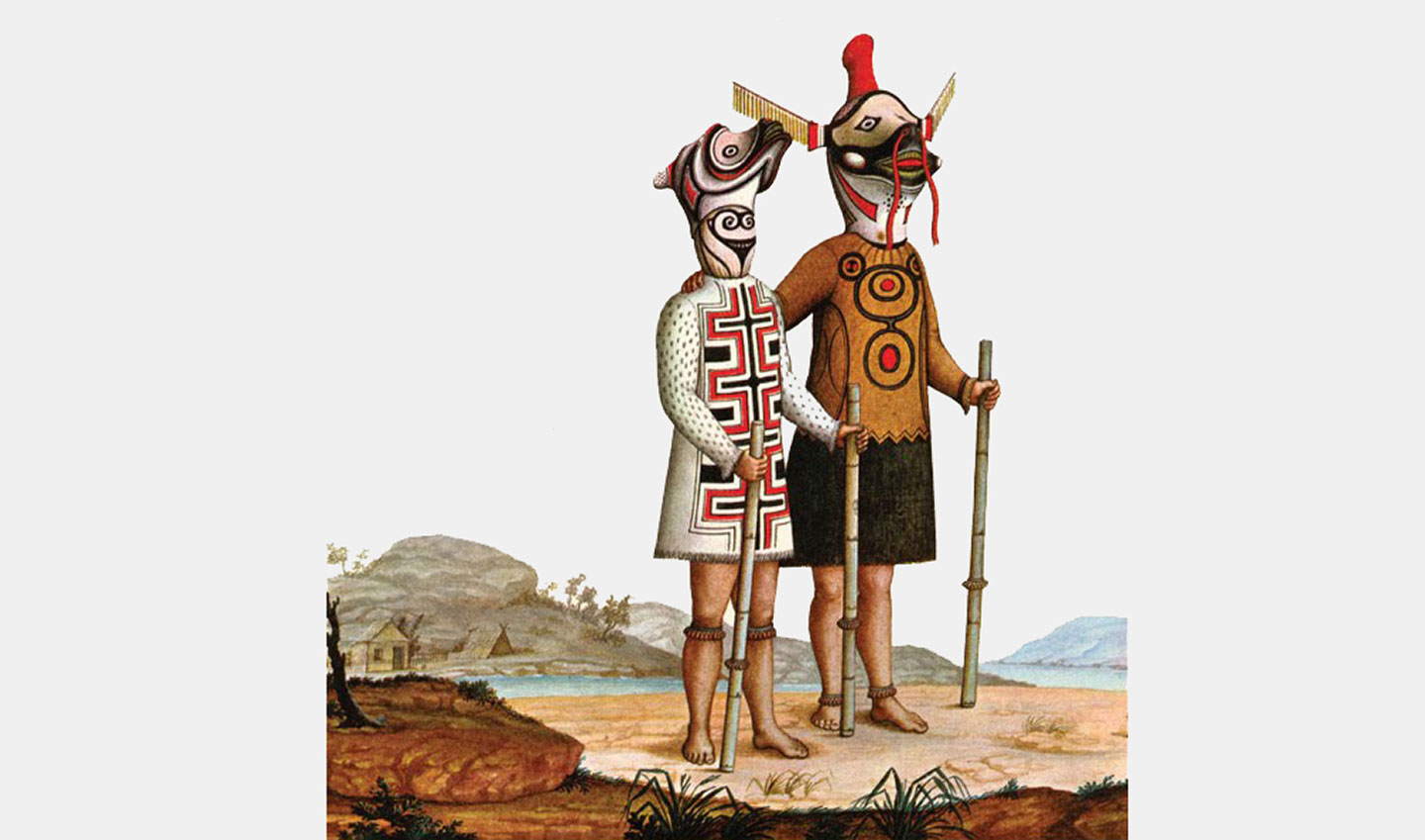

Those beings in indigenous cosmologies that we classify under the heteroclitic category of “spirits” generally tend to be entities that have preserved the ontological lability of the originary people, and which, for that reason, characteristically oscillate between human, animal, vegetable, etc.

Viveiros de Castro, 1996.

The difference between animism and totemism is, in this regard, pace Philippe Descola and with Marshall Sahlins, not very clear and possibly not very meaningful. See Descola, Par-Delà Nature et Culture (Paris: Gallimard, 2005); Sahlins, “On the Ontological Scheme of Beyond Nature and Culture,” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 4/1 (2014): 281–90.