For a critique of the modern subject as autocratic, in the context of a Latour- and Stengers-inspired curatorial project, see Susanne Karr, “We Have Never Been Alone: The Continuing Appeal of Animism,” Springerin →.

In contrast to his later critics, Greenberg himself rarely (if ever) used the term; however, his “Kantian” definition of modernism in terms of “the use of the characteristic methods of a discipline to criticize the discipline itself, not in order to subvert it but in order to entrench it more firmly in its area of competence” is of course a definition of Modernist art’s autonomous self-development. Clement Greenberg, “Modernist Painting” (1960), in The Collected Essays and Criticism 4: Modernism With a Vengeance, 1957–1969, ed. John O’Brian (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1993), 85.

Theodor W. Adorno, Aesthetic Theory (1970), trans. Robert Hullot-Kentor (London: Bloomsbury, 2013), 7.

Die Freiheit und die Institution was broadcast on WDR television on June 3, 1967, presented by Alexander von Cube. While the debate’s title uses the term “freedom,” Adorno does at one point recast the issue as being one of autonomy, of self-determination. A recording of this broadcast has been posted online with a 1965 date (possibly due to a confusion with a famous 1965 radio debate between Adorno and Gehlen, “Ist die Soziologie eine Wissenschaft vom Menschen?”), which a number of recent German academic publications have erroneously taken for a fact. Right at the beginning of the broadcast, the reference to the dissolution of the Provo movement (which happened on May 13, 1967) should make it patently clear that 1965 cannot be the year of this debate. The footage shown is from Louis van Gasteren’s 1966 film Omdat mijn fiets daar stond, which documents police violence against people (Provos and others) who had just attended the opening of an exhibition that documented and criticized police actions during the wedding of Princess Beatrix and Claus von Amsberg.

In 1962, Grootveld witnessed an evening of “Parellele Aufführungen neuester Musik” organized by Wolf Vostell, and including contributions by Dick Higgins, Alison Knowles, and Nam June Paik; the evening of events became a model for Grootveld’s happenings when Vostell attempted to perform a décollage action outside, on the street, and the police intervened. According to a report published by the weekly Haagse Post at the time, Grootveld tried to convince the remaining attendees that Amsterdam was to become a magic center. See Ludo van Halem, “Parallele Aufführungen neuester Musik. Een Fluxusconcert in kunsthandel Monet,” Jong Holland 6, no. 5 (1990): 26 (quoting from Haagse Post, October 13, 1962).

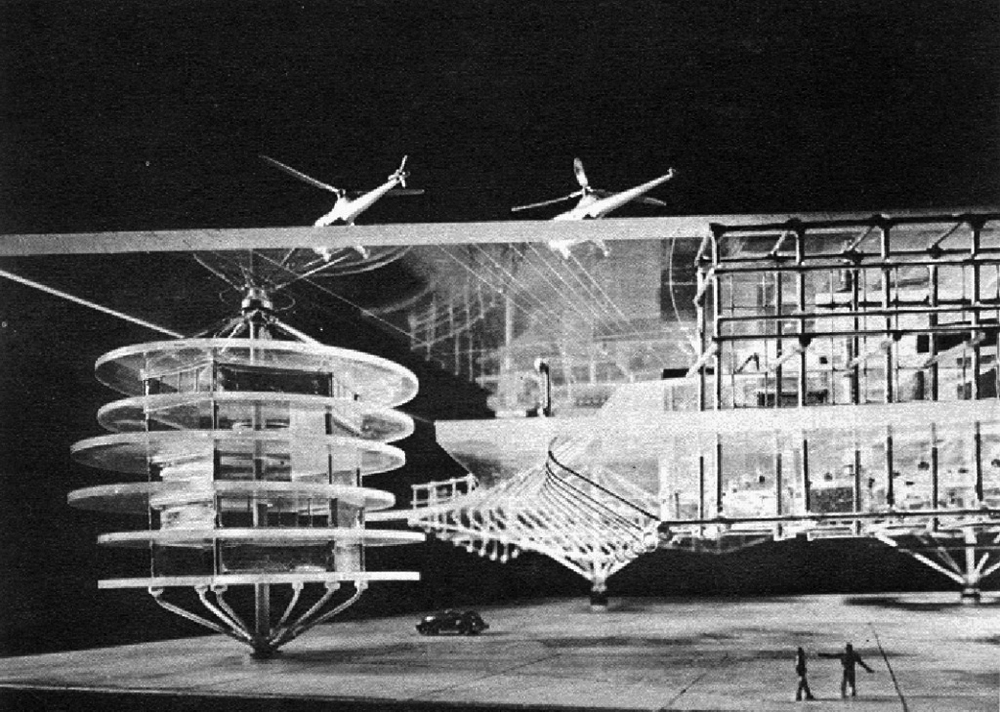

Constant and New Babylon were fêted in Provo 4 (October 1965).

In this sense, any mention of “aesthetic autonomy” should come with immediate qualifications; otherwise the result will be a conceptual fetish that negates a core quality of the aesthetic itself. On “aesthetic autonomy” in relation to “artistic autonomy,” see also Aesthetic and Artistic Autonomy, ed. Owen Hulatt (London: Bloomsbury, 2013).

Terry Eagleton, The Ideology of the Aesthetic (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1990), 9.

For Rancière, see “The Aesthetic Revolution and Its Outcomes: Emplotments of Autonomy and Heteronomy,” New Left Review 12 (March–April 2002), 133–51.

Herbert Marcuse, A Study on Authority (1936), trans. Joris de Bres (London: Verso, 2008), 7–8.

Ibid., 8.

Georg Lukács, “Reification and the Consciousness of the Proletariat,” in History and Class Consciousness (1922), trans. Rodney Livingstone (London?: Merlin Press, 1971), 124.

Peter Osborne, “Theorem 4: Autonomy. Can It Be Part of Art and Politics at the Same Time?,” Open 23 (2012), 116–26.

On praxis and labor see also Josefine Wikström, “Practice Comes Before Labor: An Attempt to Read Performance through Marx’s Notion of Practice,” Performance Research: A Journal of the Performing Arts 17, no. 6 (2012). DOI: 10.1080/13528165.2013.775753

The term was key to Charles de Brosses’s Enlightenment theory of “primitive” African (but implicitly also Catholic European) religion in Du culte des dieux fétiches (1760).

See, of course, the famous section on the fetishism of commodities from Capital, vol. 1 (chapter 1, section 4) →.

Stewart Martin, “The Absolute Artwork Meets the Absolute Commodity,” Radical Philosophy 146 (November–December 2007): 23.

Theodor W. Adorno, In Search of Wagner, trans. Rodney Livingstone (London: Verso, 2005), 72.

Raniero Panzieri, “Relazione sul neocapitalismo,” in La Ripresa del Marxismo-Leninismo in Italia (Milan: Sapere Edizioni, 1972), 212, quoted in Pier Vittorio Aurelli, The Project of Autonomy: Politics and Architecture Within and Against Capitalism (New York: Tenple Hoyne Buell Center/Princeton Architectural Press, 2008), 27.

Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Volume I, trans. Ben Fowkes (London: Penguin, 1990), 255.

See for instance Das automatische Subjekt bei Marx, eds. Hans-Georg Bensch and Frank Kuhne (Lüneburg: Gesellschaftswissenschaftliches Institut Hannover 1998); in recent art theory, see Kerstin Stakemeier, for instance “Art as Capital—Art as Service—Art as Industry: Timing Art in Capitalism,” in Timing: On the Temporal Dimension of Exhibiting, eds. Beatrice von Bismarck et al. (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2014), 15–38.

Hal Foster, Design and Crime and Other Diatribes (London: Verso, 2002).

Jonathan Crary, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep (London: Verso, 2013), 46.

See Byung-Chul Han, Psychopolitik. Neoliberalismus und die neuen Machttechniken (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer, 2014).

Brian Holmes, “Artistic Autonomy and the Communication Society,” Third Text 18, no. 6 (2004): 548 →.

“Self-determination is the right to choose your dependencies”; Vivian Ziherl quoted by Jonas Staal in “To Make a World, Part II: The Art of Creating a State,” e-flux journal 60 (December 2014) →.

Theodor W. Adorno, “Marginalien zu Theorie und Praxis” (1969) in Kulturkritik und Gesellschaft II (Gesammelte Schriften 10.2) (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2003), 760–82 (quotation from 776). In his attacks on “actionism,” Adorno here himself uses the impoverished and undialectical notion of praxis (as antithetically opposed to “theory”) that he accuses his opponents of employing.

Rudi Dutschke, in Uwe Bergmann, Rudi Dutschke, Wolfgang Lefèvre, and Bernd Rabehl, Rebellion der Studenten oder Die neue Opposition (Reinbek: Rowohlt, 1968), 63.

Rosenberg launched the term “action painting” with his 1952 essay “The American Action Painters” (in ARTnews 51, no. 8 (December 1952), 22–23, 48–50), which was widely supposed to be based on Jackson Pollock’s practice, although Rosenberg did not mention a single artist’s name and was much closer to De Kooning. See also my History in Motion: Time in the Age of the Moving Image (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2013), 223–32.

Allan Kaprow, “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock,” ARTnews 57, no. 6 (October 1958), 24–26, 55–57.

It should also be noted that the term came with a specifically German pedigree, as Franz Pfemfert’s legendary 1911–32 magazine had been called Die Aktion. Starting out as an expressionist periodical, Die Aktion became progressively politicized during and after WWI.

On the Subversive Aktion and its links to the SI, see Aribert Reimann, Dieter Kunzelmann: Avantgardist, Protestler, Radikaler (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2009), 49–122.

Karl Marx, “Theses on Feuerbach” (1845) →.

On April 2, 1968 the Anti-Theatre group of Horst Söhnlein, Andreas Baader, and Thorwald Proll (alongside Gudrun Ensslin) set fire to two department stores in Frankfurt—a key moment in the formation of the RAF.

Thomas Schmid, “Facing Reality: Organisation Kaputt,” Autonomie. Materialien gegen die Fabrikgesellschaft 1 (October 1975): 16–35.

The pun “Krautonomie” can be found in the correspondence of the editorial group of the neue Folge of Autonomie, which lasted from 1979 to 1986. The archive is at the IISH in Amsterdam (ARCH02930).

Karl Heinz Roth (with Elisabeth Behrens), Die “andere” Arbeiterbewegung (Munich: Trikont, second edition, 1976), 83. See also Steve Wright, “The Historiography of the Mass Worker” →.

Roth, ibid., 229.

Walter Gunteroth, “Kritik der Marxorthodoxie, Autonomie 1, 46–58, esp. 39.

Karl Heinz Roth, “Nichtarbeit, Proletarisierung,” in Autonomie. Materialien gegen die Fabrikgesellchaft 5 (February 1977): 40–42.

For a defense of Tronti and critique of Negri, see Aureli, The Project of Autonomy, 39–48.

Autonomie 1, 22.

Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, 7.

Hanns Eisler (and Theodor W. Adorno), Composing for the Films (New York: Oxford University Press, 1947), 45–61.

Ibid. In addition to Composing for the Films, see his late essay “Transparencies on Film” (1966): “There can be no aesthetics of the cinema, not even a purely technological one, which would not include the sociology of the cinema.” Adorno here stressed the photographic and “objective” nature of film. “Transparencies on Film,” trans. Thomas Y. Levin, New German Critique 24/25 (Autumn 1981–Winter 1982): 202.

See Max Weber, Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Religionssoziologie I (1920) (Tübingen: Mohr, 1988), 536–73.

Jürgen Habermas, “Modernity—An Incomplete Project,” in The Anti-Aesthetic, ed. Hal Foster (Seattle: Bay Press, 1983), 8–9.

Holmes, “Artistic Autonomy,” 548.

Andrea Fraser, “Autonomy and Its Contradictions,” Open 23 (2012): 111.

Ibid., 107.

The quotation is from Berardi’s The Soul at Work: From Alienation to Autonomy, trans. Francesca Cadel and Guiseppina Mecchia (New York: Semiotext(e), 2009) 33.

Services originated at the Kunstraum der Universität Lüneburg and subsequently toured other art spaces.

See for instance Haacke and Fraser’s obituaries of Bourdieu in October 101 (Summer 2002): 4–11.

Stakemeier, “Art as Capital,” 21.

Helmut Draxler, lecture at “Art and Its Frames: Continuity and Change,” symposium at the Kunstraum of Leuphana University Lüneburg, June 14, 2014.

August von Cieszkowski, Prolegomena zur Historiosophie (1838) (Hamburg: Felix Meiner, 1981), 150.

Jean-Paul Sartre, Critique of Dialectical Reason: Volume One, trans. Alan Sheridan-Smith (1960) (London: Verso, 2004), 228–52 inter alia.

Arnold Gehlen, “Über die Geburt der Freiheit aus der Entfremdung” (1952), in Studien zur Anthropologie und Soziologie (Munich: Luchterhand, 1963), 232–46.

Gerald Raunig, “Instituent Practices,” in Art and Contemporary Critical Practice: Reinventing Institutional Critique, eds. Gerald Raunig and Gene Ray (London: MayFly, 2009), 11.

“Langer Marsch durch die Institutionen” is a well-known phrase in Germany; for Dutschke’s original use, see Manfred Kittel, Langer Marsch durch die Institutionen? Politik und Kultur in Frankfurt nach 1968 (Munich: Oldenbourg, 2011), 6.

On the Council for Maintaining the Occupation, see René Viénet’s text from Enragés and Situationists in the Occupations Movement (1968) at →.

André Rottmann has focused on the transformation of the institution from site into network: “Networks, Techniques, Institutions: Art History in Open Circuits,” Texte zur Kunst 81 (2011), 142–44. Hito Steyerl writes about the “integration into precarity” in “The Institution of Critique” in Art and Contemporary Critical Practice, 13–19.

Fredric Jameson, “Culture and Finance Capital,” Critical Inquiry 24, no. 1 (Autumn 1997): 264, 265.

Armand Mattelart, “Communication Ideology and Class Practice” (Chile, 1971), in Communication and Class Struggle, Vol. 1: Capitalism, Imperialism, eds. Armand Mattelart and Seth Siegelaub (New York/Bagnolet: International General/IMMRC, 1979), 116. Armand Mattelart, “Introduction: For a Class and Group Analysis of Popular Communication Practices,” in Communication and Class Struggle, Vol. 2: Liberation, Socialism, eds. Armand Mattelart and Seth Siegelaub (New York/Bagnolet: International General/IMMRC, 1979), 28

Crary, 24/7, 36.

“Meaning and Perspective in the Digital Humanities: A White Paper for the Establishment of a Center for Humanities and Technologies,” eds. Sally Wyat (KNAW) and David Millen (IBM) →.

Matteo Pasquinelli, “Capital Thinks Too: The Idea of the Common in the Age of Machine Intelligence,” Open!, December 11, 2015 →.

Sarah Amsler, “Beyond All Reason: Spaces of Hope in the Struggle for England’s Universities,” Representations 116 (Fall 2011): 80.

Ibid., 68.

Vidya Ashram, “The Global Autonomous University,” in Toward a Global Autonomous University, ed. The Edu-factory Collective (New York: Autonomedia, 2009), 166. See also Gerald Raunig, Factories of Knowledge, Industries of Creativity, trans. Aileen Derieg (New York: Semiotext(e), 2013).

This article is based on the introduction to the Art and Autonomy reader, to be published by Afterall later this year.