See Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press, 2003); Huey Copeland, Bound to Appear: Art, Slavery, and the Site of Blackness in Multicultural America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013); Kobena Mercer, Discrepant Abstraction (London: Institute of International Visual Arts, 2006); Kellie Jones, “‘It’s Not Enough to Say ‘Black is Beautiful’: Abstraction at the Whitney 1969–1974,” in EyeMinded: Living and Writing Contemporary Art (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011): 397–427; Adrienne Edwards, Blackness in Abstraction (New York: Pace Gallery, 2016)

See Angela Y. Davis, “Afro Images: Politics, Fashion, Nostalgia,” Critical Inquiry, vol. 21, no. 1 (Autumn 1994): 37–45; David Marriott, On Black Men (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000); Richard Powell, Cutting a Figure: Fashioning Black Portraiture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008); Krista Thompson, An Eye for the Tropics: Tourism, Photography, and Framing the Caribbean Picturesque (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006); Leigh Raiford, Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare: Photography and the African American Freedom Struggle (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011).

See Sylvia Wynter, “Sambos and Minstrels,” Social Text 1 (Winter 1979): 149–156; Hortense Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” Diacritics, vol. 17, no. 2 (Autumn 1987): 64–81; Fred Moten, In the Break; Fred Moten, “Blackness and Nothingness,” South Atlantic Quarterly, vol. 112, no. 4 (Fall 2013): 779; Frank Wilderson, “Of Grammar and Ghosts: The Performative Limits of African Freedom,” Theatre Survey, vol. 50, no. 1 (May 2009): 119–125; Hannah Black, “Fractal Freedoms,” Afterall 41 (2016): 4–9.

Adrienne Edwards, “Blackness in Abstraction,” Art in America, vol. 103, No.1 (January 2015): 62–69.

Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, trans. Charles Lam Markmann (New York: Grove Press, 1967), 112.

For a global visual history of the raised fist, please see art historian Lincoln Cushing’s work-in-progress “A Brief History of the Clenched Fist Image” →.

As Danny Widener has noted, during his time in Los Angeles, Hammons worked closely alongside Social Realist Charles White, which undoubtedly influenced Hammons’s work in Southern California.

Richard Powell, Black Art and Culture in the 20th Century (London: Thames and Hudson): 152–154.

See Kellie Jones, “Interview with David Hammons,” Real Life Magazine 16 (Autumn 1986): 249.

Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, 112.

For more on the relationship between surface and print, see David Joselit, “Notes on Surface: Towards a Genealogy of Flatness,” Art History, vol. 23, no.1 (March 2000): 19–34.

I am grateful for Nicole Archer’s insights on Hammons’s use of his own skin during the process of impression in his Body Prints series.

Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 111.

Ibid., 120.

There is much to be said about the relationship between Hammons’s works and the historical European avant-garde. Indeed, Hammons himself was compelled by Yves Klein’s Anthropometries works, and many of the prints created aesthetically recall and depart from avant-garde abstraction. For more on the relationship between black abstract or conceptual practices and the historical avant-garde, see the insightful works of Adrienne Edwards, Hannah Black, and Adam Pendleton: Adrienne Edwards, Blackness in Abstraction (New York: Pace Gallery, 2016); Hannah Black, “Fractal Freedoms”; Adam Pendleton, Black Dada Manifesto, 2008. For more on the subterranean, underground, and covert possibilities of black radical insurgency, see Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study (New York: Minor Compositions, 2013).

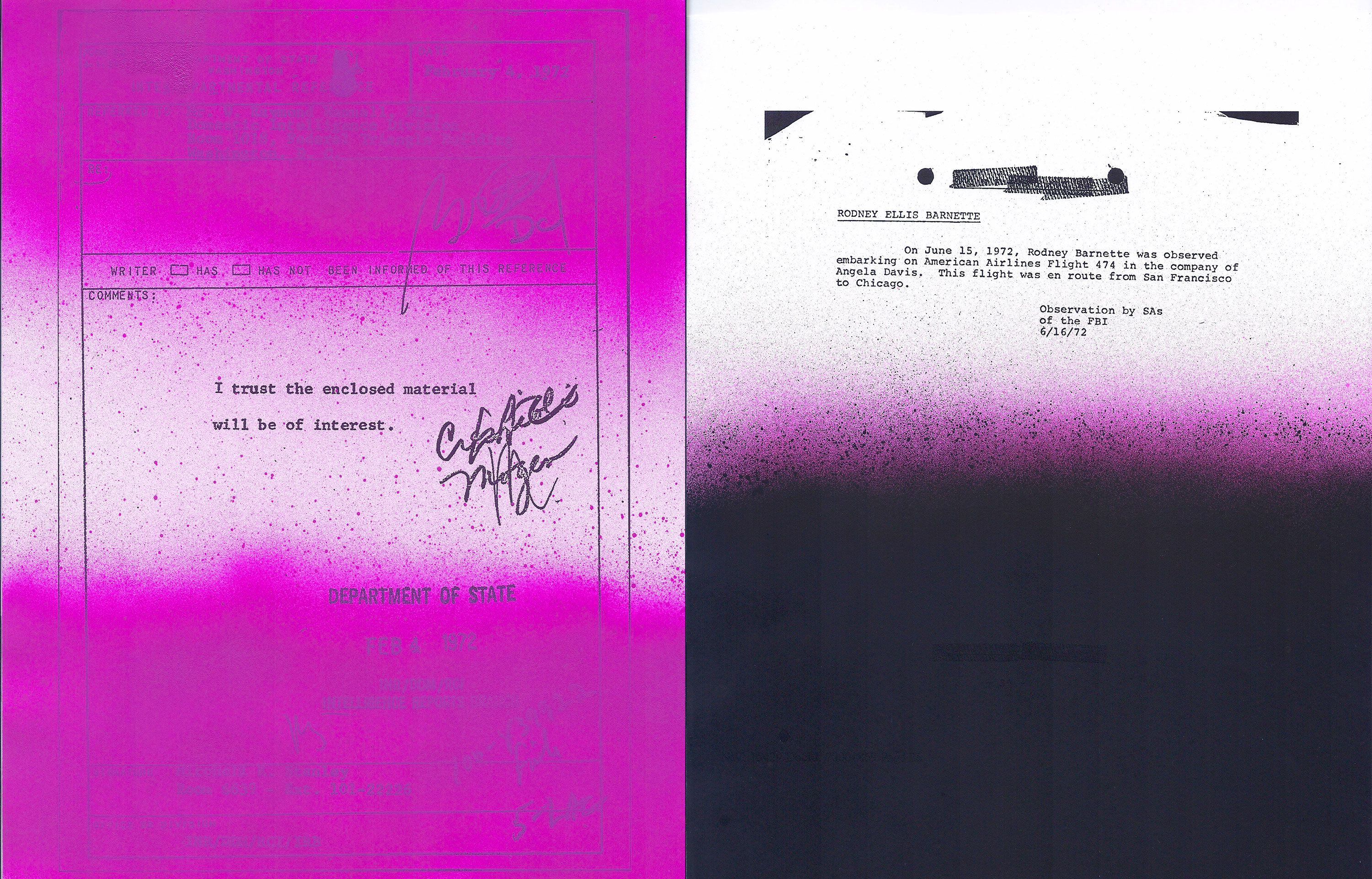

COINTELPRO effectively destroyed radical social movements in the US by engaging in infiltration, sabotage, arrest, false imprisonment, and, in some cases, murder. The impacts of this program are lasting, from radicals who are still imprisoned based on COINTELPRO operations, to the many communities who were psychologically traumatized due to infiltration and police terror. In addition to these immediate and very material impacts, COINTELPRO advanced and expanded state intelligence programs, and indeed legitimated surveillance, policing, and the criminalization of political activists, thus justifying the suspension of legal protections and the expansion of governmental power. Part and parcel of this program was the production of a jaw-dropping amount of documentation of these operations, often organized around individual political activists in an attempt to discredit and criminalize their political work. For more, see Jim Vander Wall and Ward Churchill, Agents of Repression (Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2002); Andres Alegria, Prentis Hemphill, Anita Johnson, and Claude Marks, 2012, “COINTELPRO 101,” DVD, San Francisco: Freedom Archives.

Maria L La Ganga, “Black Panthers 50 years on: art show reclaims movement by telling ‘real story.’ The Guardian, October 8, 2016 →.

Angela Davis, Angela Davis: An Autobiography (New York: International Publishers, 1988), 360.

Rodney and Sadie Barnette, “A Panther’s Story Becomes Art: A conversation between artist Sadie Barnette and her father and former Black Panther Rodney Barnette,” Oakland Museum of California blog, November 4, 2016 →.

There is a potentially dynamic relationship here to South Asian and Arab diasporic artists who also work through the politics of redaction in relationship to the prolonged War on Terror. As several scholars have noted, COINTELPRO piloted and advanced state intelligence programs and provided the groundwork for the post-9/11 PATRIOT ACT. Scholars like Anjali Nath, Ronak Kapadia, and Sara Mameni have noted how contemporary South Asian and Arab diasporic artists have all manipulated the redaction into an aesthetic form in their practices. For more, see Anjali Nath, “Beyond the Public Eye: On FOIA Documents and the Visual Politics of Redaction,” Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, vol. 14, no. 1 (2013): 21–28; Ronak Kapadia, “Kissing the Dead Body: US Military Imprisonment and the Evidence of Things Not Seen,” in “Transnational Visual Cultures,” ed. Kasturi Ray, special issue of South Asian Diaspora, vol. 7, no. 1 (March 2015); Sara Mameni, “Dermopolitics and the Erotics of the Muslim Body in Pain,” in “Sentiment and Sentience: Black Performance Since Scenes of Subjection,” eds. Sampada Aranke and Nikolas Oscar Sparks, special issue of Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory, vol. 27, no. 1 (forthcoming March 2017).

See Natsu Taylor Saito, “Whose liberty? Whose security?: The USA PATRIOT Act in the Context of COINTELPRO and the Unlawful Repression of Political Dissent,” Oregon Law Review, vol. 81, no. 4 (2002): 1051–1131.

Krista Thompson, Shine: The Visual Economy of Light in African Diaspora Aesthetic Practice (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), 225.

Rodney and Sadie Barnette, “A Panther’s Story Becomes Art.”

For a brilliant study on the uses of photographic technology (vis-à-vis the mugshot) in the expansion of state power, see Allan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive: the use and classification of portrait photography by the police and social scientists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries,” October 39 (Winter 1989): 3–64. For a lucid study on the relationship between the black freedom struggle’s uses of photography, see Leigh Raiford, Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare: Photography and the African American Freedom Struggle (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011).

Sadie Barnette’s work is indeed an extension of Zora Neale Hurston’s notion of “the will to adorn” as a “notable characteristic” of black American literary aesthetics. See Zora Neale Hurston, “Characteristics of Negro Expression,” 1934. Reprinted in The Gender of Modernism: A Critical Anthology, ed. Bonnie Kime Scott (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990), 176, 178.

For more on the relationship between blackness and current debates in new materialisms, see Huey Copeland, “Tending-toward-Blackness,” October 156 (Spring 2016): 141–144.

I am grateful and indebted to Nikolas Oscar Sparks for his insightful and suggestive use of the phrase “black life matter” in our conversations about this article, and Hammons’s and Barnette’s respective works more generally.