Whether through the vocabulary of alienation or that of deracination, Francophone criticism has probably conceptualized this process of the “exit from oneself ” best. See in particular Aimé Césaire, Discourse on Colonialism, trans. Joan Pinkham (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2000); Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, trans. Charles Lam Markmann (New York: Grove, 1967); Hamidou Kane, Ambiguous Adventure (London: Heinemann, 1972); Fabien Eboussi Boulaga, La crise du Muntu: Authenticité africaine et philosophie (Paris: Présence Africaine, 1977); and Fabien Eboussi Boulaga, Christianity without Fetishes: An African Critique and Recapture of Christianity (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1984).

This applies in particular to Anglophone work in Marxist political economy. See, for example, Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, rev. ed. (Washington, DC: Howard University Press, 1982); or the works of authors such as Samir Amin, Le développement inégal: Essai sur les formations sociales du capitalisme périphérique (Paris: Minuit, 1973).

On falsification and the necessity to “re-establish historical truth,” see, for example, the work of nationalist historians: Joseph Ki-Zerbo, Histoire de l’Afrique noire, d’hier à demain (Paris: Hatier, 1972); and Cheikh Anta Diop, The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality, trans. Mercer Cook (New York: L. Hill, 1974).

On the problematic of slavery as social death, see Orlando Patterson, Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982).

Foucault, The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978–79, trans. Graham Burchell (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 64, 66.

Ibid., 67.

Tocqueville, Democracy in America: Historical-Critical Edition of “De la démocratie en Amérique,” ed. Eduardo Nolla, trans. James T. Schleifer (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2012), 516–17.

Ibid., 517–18.

Ibid., 549, 551.

Ibid., 552.

Ibid., 555, 566.

Ibid., 572, 578.

On the centrality of the body as the ideal unity of the subject and the locus of recognition of its unity, its identity, and its value, see Umberto Galimberti, Les raisons du corps (Paris: Grasset, 1998).

On this point and those that precede it, see, among others, Pierre Pluchon, Nègres et Juifs au XVIIIe siècle: Le racisme au siècle des lumières (Paris: Tallandier, 1984); Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu, De l’esprit des lois, vol. 1 (Paris: Garnier/Flammarion, 1979); Voltaire, “Essais sur les moeurs et l’esprit” des nations et sur les principaux faits de l’histoire depuis Charlemagne jusqu’à Louis XIV,” in OEuvres complètes (Paris: Imprimerie de la Société Littéraire et Typographique, 1784), vol. 16; and Immanuel Kant, Observations sur le sentiment du beau et du sublime, trans. Roger Kempf (Paris: Vrin, 1988).

Thomas R. Metcalf, Ideologies of the Raj (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994).

The most developed institutional form of this economy of alterity was the apartheid regime, in which hierarchies were of a biological order. It was an expanded version of indirect rule. See Lucy P. Mair, Native Policies in Africa (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1936); and Frederick D. Lugard, The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa (London: W. Blackwood and Sons, 1980).

See the texts gathered in Henry S. Wilson, Origins of West African Nationalism (London: Macmillan, 1969).

See, for example, Nicolas de Condorcet, “Réflexions sur l’esclavage des Nègres (1778),” in OEuvres (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1847), vol. 7.

Edward W. Blyden, Christianity, Islam and the Negro Race (Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 1994); and Edward W. Blyden, Liberia’s Offering (New York: John A. Gray, 1862).

See, for example, the texts gathered in The African Liberation Reader, 3 vols., eds. Aquino de Bragança and Immanuel Wallerstein (London: Zed, 1982).

See Immanuel Kant, Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View (Chicago: Southern Illinois Press, 1978).

On this point, see L’idée de la race dans la pensée politique française contemporaine eds. Pierre Guiral and Emile Temime (Paris: Editions du cnrs, 1977).

You can see the centrality of this theme in Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks; Césaire, Discourse on Colonialism; and, in a general sense, the poetry of Léopold Sédar Senghor.

W. E. B. Du Bois, The World and Africa: An Inquiry into the Part Which Africa Has Played in World History (New York: International Publishers, 1946).

To this effect, see the final pages of Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks.

This is the thesis of Léopold Sédar Senghor, “Negritude: A Humanism in the Twentieth Century,” in Colonial Discourse and Postcolonial Theory: A Reader, eds. Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman (New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1994), 27–35.

In this regard, see the critique of the texts of Alexander Crummell and W. E. B. Du Bois in Kwame Anthony Appiah, In My Father’s House: Africa in the Philosophy of Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), chaps. 1 and 2. See also Kwame Anthony Appiah, “Racism and Moral Pollution,” Philosophical Forum, vol. 18, nos. 2–3 (1986–1987): 185–202.

Léopold Sédar Senghor, Liberté I: Négritude et humanisme (Paris: Seuil, 1964); and Senghor, Liberté III: Négritude et civilisation de l’universel (Paris: Seuil, 1977).

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Reason in History, trans. Robert S. Hartman (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1953).

In the Francophone world, see in particular the works of Diop and, in the Anglophone world, the theses on Afrocentricity offered by Molefi Kete Asante, Afrocentricity (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1988).

See, among others, Théophile Obenga, L’Afrique dans l’Antiquité: Égypte pharaonique, Afrique noire (Paris: Présence Africaine, 1973)

Paradoxically, we find the same impulse and the same desire to conflate race and geography in the racist writings of White colonists in South Africa. For details on this, see John M. Coetzee, White Writing: On the Culture of Letters in South Africa (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1988). See especially the chapters on Sarah Gertrude Millin, Pauline Smith, and Christiaan Maurits van den Heever.

They must “return to the land of (their) fathers and be at peace,” as writes Blyden in Christianity, 124.

Africa as a subject of racial mythology can be found as much in the works of Du Bois as those of Diop or else Wole Soyinka; for the latter, see Soyinka, Myth, Literature, and the African World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976).

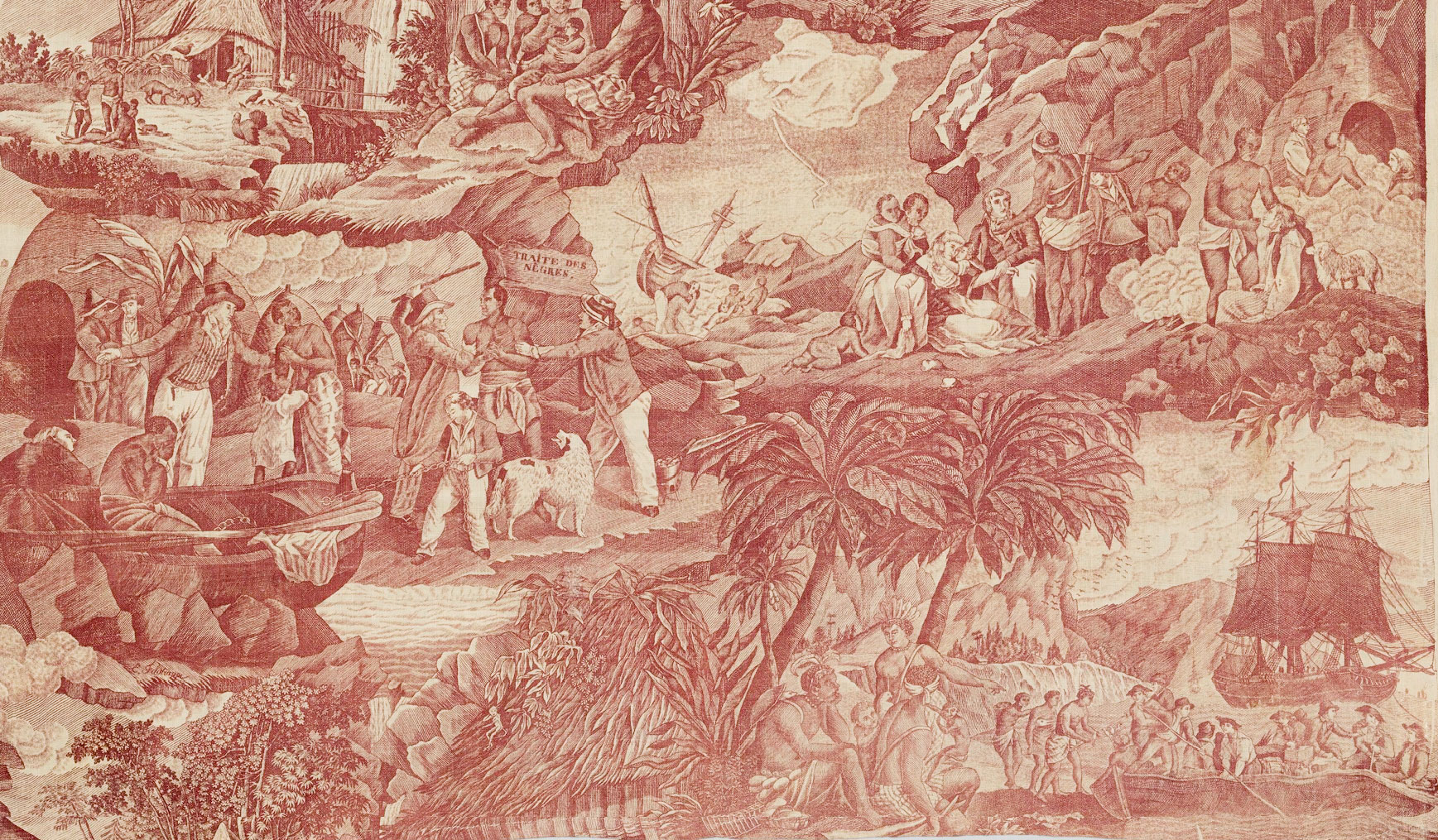

Joseph C. Miller, Way of Death: Merchant Capitalism and the Angolan Slave Trade, 1730–1830 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1988).

This text is an excerpt from Critique of Black Reason by Achille Mbembe, translated by Laurent Dubois and published by Duke University Press in March 2017.