Wassily Kandinsky, “Rückblicke” (1913), in Theories of Art 3: From the Impressionists to Kandinsky, ed. Moshe Barasch (Routledge, 2000), 296.

Lázslo Moholy-Nagy, Moholy Malerei Film (Albert Langen, 1927), 66–68, 70.

Akira Mizuta Lippit, Atomic Light (Shadow Optics) (University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 30–60.

Peter Galison, Image & Logic: A Material Culture of Microphysics (University of Chicago Press, 1997), 464.

Gÿorgy Kepes, The New Landscape in Art and Science (Paul Theobald and Co., 1956), 200–203.

Galison, Image & Logic, 65–141.

Galison, Image & Logic, 143–60.

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (1980), trans. Richard Howard (Hill and Wang, 1981), 80.

Tom Gunning, “What’s the Point of an Index? or, Faking Photographs,” in Still Moving: Between Cinema and Photography, eds. Karen Beckman and Jean Ma (Duke University Press, 2008), 26.

“Das ist die Dialektik des Index: Er brüllt aus der Wirklichkeit, sagt aber erstmal nichts.” Diedrich Diederichsen, Körpertreffer: Zur Ästhetik der nachpopulären Künste (Suhrkamp, 2017), 19.

Carter Stone and Wolfgang Paalen, “During the Eclipse” in Wolfgang Paalen, Form and Sense (Problems of Contemporary Art, no. 1) (Wittenborn, 1945), 21.

See Wolfgang Paalen, “The Dialectical Gospel,” in Dyn, no. 2 (July–August 1942), 54–59. This issue also contains Paalen’s famous “Inquiry on Dialectic Materialism,” 49–54.

Wolfgang Paalen, “Art and Science” (1942), in Form and Sense, 64.

Wolfgang Paalen, “On the Meaning of Cubism Today” (1944), in Form and Sense, 30.

Letter from Paalen to Gordon Onslow Ford, August 26, 1945, quoted in Annette Leddy, “The Painting Aesthetic of Dyn,” in Farewell to Surrealism. The Dyn Circle in Mexico, eds. Annette Leddy and Donna Conwell (Getty Research Institute, 2012), 33.

As Andreas Neufert puts it in his biography of Paalen: “Paalen wiederum schlug sich mit Einwänden und Skrupeln gegen Matta herum, der von Hiroshima und Nagasaki einfach gestrickte Rückschlüsse auf seine Malerei ziehen wollte.” Neufert, Auf Liebe und Tod: Das Leben des Surrealisten Wolfgang Paalen (Parthas, 2015), 527.

Wolfgang Paalen, “Brief Outline,” part of the unpublished typescript of The Beam of the Balance (1946). I am grateful to Andreas Neufert for making this script available to me.

Bartnett Newman, “The New Sense of Fate” (1948), in Selected Writings and Interviews, ed. John O’Neill (University of California Press, 1990), 165.

Newman, “The New Sense of Fate,” 169.

Kurosawa’s I Live in Fear (1955) is an example of a film that addresses the social and psychological fallout of the threat (and, for Japan, the memory) of nuclear war.

Newman, “The New Sense of Fate,” 169.

See also Stephen Petersen, “Explosive Propositions: Artists React to the Atomic Age,” in Science in Context 17, no. 4 (2004): 579–609.

Günther Anders, “Tagebuch aus Hiroshima und Nagasaki” (1958), in Hiroshima ist überall (München, 1982), 64.

“Dass diese verspätete offizielle Vorliebe für Zerstörung von Gegenstandsformen in der Kunst (bzw. die Propaganda für den Genuss an dieser Zerstörung und die Verhöhnung derer, die diesen Kunstfortschritt nicht mitmachten) mit der effektiven Zerstörung der Welt synchronisiert aufgetreten ist, war kein Zufall. Und ebensowenig ist es ein Zufall, dass die Zerstörung der Welt, für die hier in Hiroshima die Generalprobe abgehalten wurde, ihr Monument in einem ‘non-objective object’ gefunden hat.” Anders, “Tagebuch aus Hiroshima und Nagasaki,” 65. Author’s translation.

On both movements, see Petersen, “Explosive Propositions.”

Beniamino Dal Fabbro, “Definition of the Nuclearists” (1953), in Arte Nucléaire, ed. Tristan Sauvage (Arturo Schwarz) (Éditions Villa, 1962), 207.

Asger Jorn, unpublished article quoted in Sauvage, Arte Nucléaire, 36.

Surrealist Intrusion in the Enchanters’ Domain, eds. André Breton and Marcel Duchamp (D’Arcy Galleries, 1960), 40–41; André Breton, “Enrico Baj” (1963), in Le Surréalisme et la peinture (Gallimard, 1965), 395–400. The comment on Baj’s Lucretius illustrations (a portolio of thirty-six prints published in 1958) is on 398.

“Matta a toujours été attiré par les travaux des physiciens modernes sur la propagation des ondes et les radiations, et par les transformations gigantesques que les savants viennent de faire subir à la matière.” Robert Tenger, “Note de l’éditeur,” in Denis de Rougemont, Lettres sur la bombe atomique (Brentano’s, 1946), 11. Translations from the French by Michael Andrews for my article “World History and Earth Art,” e-flux journal 49 (November 2013), on which this discussion of de Rougemont is based →.

See last page of “On the Survival of Certain Myths and on Some Other Myths in Growth or Formation,” in First Papers of Surrealism, eds. André Breton and Marcel Duchamp (Coordinating Council of French Relief Societies, 1942), unpaginated.

André Breton, “Prolegomena to a Third Manifesto of Surrealism or Else (sic)” in VVV no. 1 (1942): 18–26. Matta selected preexisting images but also used one of his own drawings of Les Grands Transparents. On Breton, Matta, and the cultural context in which Les Grands Transparents emerged, with a focus on fantastic fiction and sci-fi, see also Gavin Parkinson, Futures of Surrealism: Myth, Science Fiction and Fantastic Art in France 1966–1969 (Yale University Press, 2015), 19–36.

Christian de Maussion, “Mythomattaque: Entretien avec Matta,” L’Autre journal 9 (1986): 39.

Louis Pauwels and Jacques Bergier, Morning of the Magicians: Secret Societies, Conspiracies, and Vanished Civilizatons (1960), trans. Rollo Myers (Destiny Books, 2009), 393.

Pauwels and Bergier, Morning of the Magicians, 393.

Planète no. 1, undated (1961): quotations from 8, 131, 75.

Pierre Guérin, “Hypothèses sur les mondes habités,” Planète no. 1: 30, 32.

Parkinson, Futures of Surrealism, 167.

A blurb by Olivier Surel on the back cover of The Quadruple Object of Philosopy.

Internationale Situationniste no. 7 (April 1962), which opened with an attack on nuclear bunkers and the “geopolitics of Hibernation,” also contains a kind of attack ad about Planète (46), with the header “Si vous lisez ‘Planète’ à haute voix, vous sentirez mauvais de la bouche!” (“If you read Planète out loud, your mouth will hurt!”); further down, there’s a reference to the mutation motif in the style of a Pauwels/Bergier subheading: “Et s’il le faut, mutons ensemble!” (“Let’s mutate together if we must!”)

Leslie A. Fiedler. “The New Mutants,” in Partisan Review 43, no. 4 (Fall 1965): 505–25.

The Realists (Henry Flynt), “Overthrow the Human Race!,” in Happening & Fluxus, ed. H. Sohm (Kölnischer Kunstverein 1970), unpaginated; see also Branden W. Joseph, Beyond the Dream Syndicate: Tony Conrad and the Arts after Cage (Zone Books, 2008), 210, 419 (note 135). Joseph notes that Flynt founded his “party,” The Realists, in 1968, and dates the “Overthrow” manifesto as “ca. 1969.”

In the third issue of Planète, on 124, we encounter speculations on Nazis founding a secret order, “cosmonazism” (helpfully illustrated with a photo of a rocket), after the war, one that would allow them to subdue not just earth but other planets, employing more subtle methods than the crude means used the first time around.

Robert Jungk, “L’Intelligence prend le pouvoir,” in Planète no. 1: 15–17.

Oddly enough, in a move that no doubt would have pleased Pauwels and Bergier, in one of the book’s footnotes Jungk gives credence to the “Nazi UFO” myth still beloved by esoteric (and neofascist) conspiracy theorists. Robert Jungk, Brighter than a Thousand Suns: A Personal History of the Atomic Scientists (1958), trans. James Cleugh (Harcourt, 1986), 87.

As is evident from the title, Breton presents science as a lost cause altogether, rather than defending it against its instrumentalization, against its reduction to Zweckvernunft. This is a symptom of Breton’s progressive withdrawal into esotericism. See André Breton, “Démasquez les physiciens, videz les laboratoires!” (1958) →.

José Pierre (et al.), Les Fausses cartes transparentes de Planète, published as Le Petit Écrasons 3 (1965). See also Parkinson, Futures of Surrealism, 171.

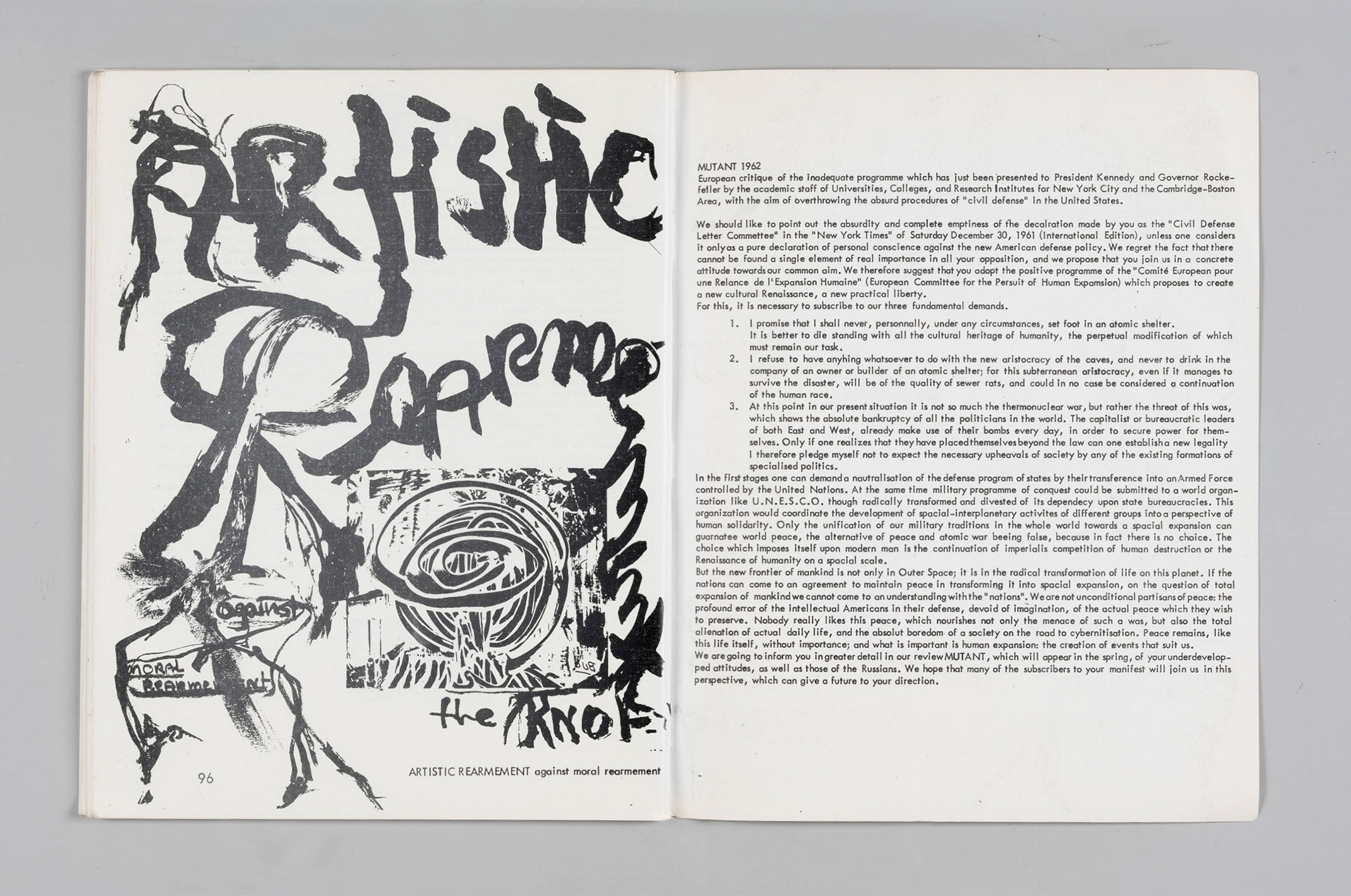

Guy Debord and Asger Jorn, “Mutant” (“European Critique of the Inadequate Program that has Just been Presented to President Kennedy and Governor Rockefeller by the Academic Staff of Universities, Colleges and Research Institutes for New York City and the Cambridge-Boston Area, with the Aim of Overthrowing the Absurd Procedures of ‘Civil Defense’ in the United States”) (January 1962), in Consmonauts of the Future: Texts from the Situationist Movement in Scandinavia and Elsewhere, eds. Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen and Jakob Jakobsen (Nebula/Autonomedia, 2015), 65.

“Géopolitique de l’hibernation,” in Internationale Situationniste, no. 7 (April 1962), 6; quoted from English translation by Ken Knabb, “Geopolitics of Hibernation,” at →. This critical motif also plays an important role in Raoul Vaneigem’s “Banalités de base,” published in the same issue of Internationale Situationiste, which can be regarded as part of the SI’s anti-Planète offensive (see note 39 above).

Roel van Duijn, Energieboekje: over de energie-krisis en de oplossing daarvan door een alternatieve technologie (Bert Bakker, 1972).

“Weesp testgebied voor Philips-Duphars Zenuwgassen,” in De Paniekzaaier no. 1 (November 1971): 6. Author’s translation.

Jaime Semprun, La Nucléarisation du monde (Éditions Gérard Lebovici, 1986), 14, 38. Author’s translation.

These volumes are represented in the artist’s library as kept in the Sigmar Polke Archiv, Cologne.

Kathrin Rottmann, “Urangestein im Atelier,” in Alibis: Sigmar Polke 1963–2010, ed. Kathy Halbreich (MoMA/Museum Ludwig/Prestel, 2015), 60–61.

Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Duke University Press, 2007), 53.

Bruno Latour, “What Is Iconoclash? Or Is There a World Beyond the Image Wars?,” in Iconoclash: Beyond the Image Wars in Science, Religion, and Art, eds. Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel (ZKM/MIT Press, 2002), 16.

In his Fukushima Trilogy (2012–14), Rouy makes use of live cam and robot footage from the Fukushima plant.

Yves Klein, quoted in Petersen, “Explosive Propositions,” 599.

As Petersen puts it, “The Void, in its emptiness and its use of strategic annihilation, also made metaphorical reference to the emptiness of nuclear obliteration” (599).

One key difference is that Polke’s piece was about a mental exercise by the artist (“Polke stellt sich vor, dass ein Teilchen diesen Raum umkreist”), whereas Brouwn’s exhibition is an invitation to the viewer to experience walking through cosmic rays.

On Barry, see also Eric C. H. de Bruyn’s discussion of his use of a different kinds of “invisible waves” with his Telepathic Piece of the same year: de Bruyn, “Vanishing Acts: Notes on a Genealogy of Dematerialisation,” in DeMATERIALISATIONS in Art and Art-Historical Discourse in the Twentieth Century (Proceedings of a conference held in Tomaszowice, Poland, on May 14–16, 2017), eds. Wojciech Bałus and Magdalena Kunińska (2018).

See Susanne Kriemann, P(ech) B(lende): Library for Radiological Afterlife (Spector Books, 2016). This book contains a version of Susan Schuppli’s essay “Radical Contact Prints,” which discusses the Bikini Atoll autoradiographs of fish (133).

See Supplement—2: Exclusion Zones (Fillip, 2017), a booklet with text by Eva Wilson and images by Kriemann.

Barthes, Camera Lucida, 80–81.

For a general critical assessment of Simon’s work, see Robert Kulisek and David Lieske, “Husbands have Got to Die!,” in Texte zur Kunst no. 100 (December 2015), 172–97.

See Thomas A. Sebeok, “Communication Measures to Bridge Ten Millennia,” technical report for the Office of Nuclear Waste Isolation (April 1984) →.

Trevor Paglen, quoted from →.

Stefan Heidenreich, “Freeportism as Style and Ideology: Post-Internet and Speculative Realism, Part II, in e-flux journal no. 73 (May 2016) →.

Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Harvard University Press, 2011).

Semprun, La Nucléarisation du monde, 39.

Stewart Martin, “The Absolute Artwork Meets the Absolute Commodity,” in Radical Philosophy no. 146 (November–December 2007): 22.

René Riesel and Jaime Semprun, Catastrophism, Disaster Management and Sustainable Submission (Roofdruk, 2014), 12.

Galison, Image & Logic, 433–88.

Galison, Image & Logic, 692. See also Thomas Haigh, Mark Priestley, and Crispin Rope, “Los Alamos Bets on ENIAC: Nuclear Monte Carlo Simulations, 1947–1948,” in IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, July–September 2014, 42–63, who fill in gaps in Galison’s account; and James Bridle, New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future (Verso, 2018), 25–32.

See Joseph Masco, The Nuclear Borderlands: The Manhattan Project in Post-Cold War New Mexico (Princeton University Press, 2006), 90–96.

This text builds on the earlier article "Apocalypse (Not) Now" in the Nordic Journal of Aesthetics (2016), and on the seminar "Nuclear Aesthetics" I taught at the Vrije Universiteit in 2018, which will be the basis of an issue of the journal Kunstlicht.