Alexandra Peers, “Charities Draw Younger Donors With Hip Events and Door Prizes,” Wall Street Journal, April 25, 1994.

“Joseph Kosuth and Felix Gonzalez-Torres: A Conversation,” Art & Design 9, no. 1–2 (1994): 76.

Tim Rollins, Felix Gonzalez-Torres (A.R.T. Press, 1993), 20.

Kevin Gray and Susan Francis Gray, Elements of Land Law, 5th ed. (Oxford University Press, 2009), 12–13. I thank Emma Waring for this reference.

Hans Ulrich Obrist, “Gonzalez-Torres, Felix,” Hans Ulrich Obrist, Interviews 1 (Charta, 2003), 311.

Miwon Kwon, “The Becoming of a Work of Art: FGT and a Possibility of Renewal, a Chance to Share, a Fragile Truce,” in Felix Gonzalez-Torres, ed. Julie Ault (SteidlDangin, 2006), 295.

Aldon Accessories Ltd. v. Spiegel, Inc., 738 F.2d 548 (2nd Cir., 1984).

Community for Creative Non-Violence v. Reid, 652 F. Supp. 1457 (D.D.C, 1987).

Community for Creative Non-Violence et. al. v. Reid, 490 U.S. 730 (1989).

Kwon, “The Becoming of a Work of Art,” 308.

The issue of the service provider and the presumptive psychological toll of fulfilling services contracted is poignantly illustrated in Employment Contract (on Felix Gonzalez-Torres), a twenty-two-minute film by Pierre Bal-Blanc, who performed as a dancer in Gonzalez-Torres’s Untitled (Go-Go Dancing Platform) in 1991. For a discussion of the film see Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (Verso, 2012), 235. The final shot of the film shows the artist physically running away from the museum.

Oral history interview with Elaine Sturtevant, July 25–26, 2007. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution →.

Susan Tallman, “The Ethos of the Edition,” Arts 61, no. 1 (September 1991): 14.

Kwon, “The Becoming of a Work of Art,” 304. The wording is from the certificate accompanying “Untitled” (Portrait of the Cincinnati Art Museum), 1994 (ARG #GF 1994-9).

Kwon, “The Becoming of a Work of Art,” 304.

A comparable situation might be when a wrapped Christo work is unwrapped. The unwrapping might constitute an unlawful alteration, although such incidents have occurred only by accident.

Quoted in David Deitcher, “Contradictions and Containment,” Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Catalogue Raisonné (Cantz, 1997), 106.

Clara Hemphill, “Is It Art, Or Is It Candy?,” New York Newsday, April 18, 1995.

Two sheets from Untitled (Somewhere better/Nowhere better) (1990) were sold on eBay in October 2015 for $44.25 →.

Andrea Rosen, “‘Untitled’ (The Neverending Portrait),” Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Text, ed. Dietmar Elger, exhibition catalog (Cantz, 1997), 46–47.

Estelle Schwartz, letter to James Demetrion, March 17, 1994. The work referred to the paper stack Untitled (1989/90). Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 05-072, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Dept. of Public Programs/Curatorial Division, Curatorial Correspondence, 1987–1994, box 1.

Philippe Ségalot, letter to James Demetrion, May 16, 1994. “As the particular white beads this work is partly composed with are impossible to find anymore, the work (Untitled (Chemo)) couldn't be identically replaced should it be damaged during the show and this is why I have indicated its market value.” Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 05-072, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Dept. of Public Programs/Curatorial Division, Curatorial Correspondence, 1987–94, box 1.

Andrea Rosen Gallery, Felix Gonzalez-Torres Stacks, undated. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 05-072, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Dept. of Public Programs/Curatorial Division, Curatorial Correspondence, 1987–94, box 1.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, quoted by Bruce Ferguson, Rhetorical Image (New Museum of Contemporary Art, 1990), 48.

Barbara MacAdam, “Sweet Horrors,” Art News 94, no. 5 (May 1995): 40.

“Exhibition copy” was used by institutions; they were also called “extra copies.” Letter from Amada Cruz to Philippe Ségalot, September 12, 1994. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 05-072, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Dept. of Public Programs/Curatorial Division, Curatorial Correspondence, 1987–94, box 1.

Amada Cruz, untitled note to registrar Barbara Freund, May 13, 1994. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 05-072, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Dept. of Public Programs/Curatorial Division, Curatorial Correspondence, 1987–94, box 1. Hirshhorn staff expressed great concern over how to replace crushed beads, a problem that meant asking what constituted an acceptable substitute to the lender to whom the museum owed a legal responsibility via the loan agreement.

Jack Balkin and Sanford Levinson, “Interpreting law and music: Performance notes on ‘The Banjo Serenader’ and “The Lying Crowd of Jews,” Cardozo Law Review 20 (1999): 1513–72.

Hans Ulrich Obrist, “KünstlerInnenporträts – Auszüge: Felix Gonzalez-Torres,” Der Standard, January 10, 1996.

Richard Marshall, letter to Richard Gagliano, April 12, 1991; Registrar Memorandum to Public Education and Security, April 21, 1991. Whitney Museum of American Art, Frances Mulhall Achilles Library, Exhibitions 1931–2000 Archives, “1991 Biennial,” Box 155.

Letter from Cora Rosevear to James Demetrion, April 28, 1994. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 05-072, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Dept. of Public Programs/Curatorial Division, Curatorial Correspondence, 1987–94, box 1.

17 U.S. Code §106A (c)(2)

Jo Ann Lewis, “‘Traveling’ Light: Installation Artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres Shines at the Hirshhorn,” Washington Post, July 10, 1994. Terms of the MoMA installation were set forth in a letter from Cora Rosevear to James Demetrion, April 28, 1994. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 05-072, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Dept. of Public Programs/Curatorial Division, Curatorial Correspondence, 1987–94, box 1.

The Foundation takes a role by providing loan guidelines, or sample loan agreements upon request, although owners are not obligated to do so.

Jennifer Flay, letter to James Demetrion, March 17, 1994. Flay was conveying the wishes of Marcel Brient, the owner of Untitled (Blood) (1992), which the Hirshhorn borrowed. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 05-072, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Dept. of Public Programs/Curatorial Division, Curatorial Correspondence, 1987–94, box 1.

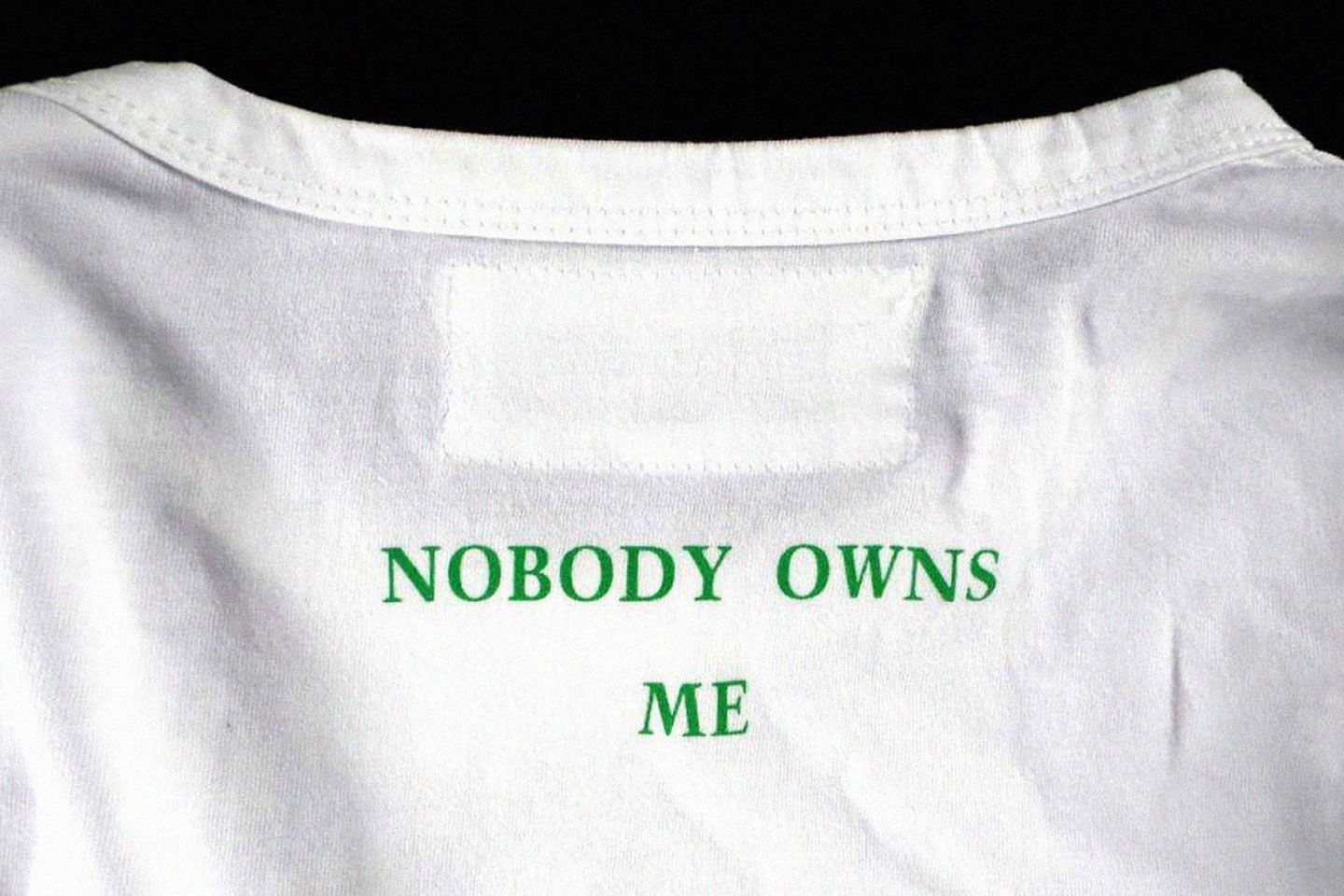

John Tain, “The Things You Own End Up Owning You: Art in the 1990s,” unpublished symposium comments, University of Michigan, October 24, 2015.

As quoted in Kwon, “The Becoming of a Work of Art,” 308. From the certificate for Untitled (1989) (ARG-#GF 1989-20), 4.

Emma Waring, email communication with the author, November 11, 2014.

Kathy Watt, memorandum to Amada Cruz, January 11, 1993. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 05-072, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Dept. of Public Programs/Curatorial Division, Curatorial Correspondence, 1987–94, box 1.

Letter from Amada Cruz to Philippe Ségalot, April 4, 1994. Accession 05-072, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Dept. of Public Programs/Curatorial Division, Curatorial Correspondence, 1987–94, box 1.

Keith N. Hylton, Tort Law: A Modern Perspective (Cambridge University Press, 2016), 262.

Obrist, “KünstlerInnenporträts – Auszüge: Felix Gonzalez-Torres.”

Rollins, 13.

Rollins, 13.

Jim Lewis, “Master of the Universe,” Harper’s Bazaar, January 1995, 133.

Maurice Berger, “The Crisis of Civil Rights,” Civil Rights Now (Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art, 1995), 46.

This text is excerpted from Joan Kee, Models of Integrity: Art and Law in Post-Sixties America, forthcoming from University of California Press in March 2019.