Fred Moten, from “all topological last friday evening,” The Little Edges (Wesleyan, 2016).

To Pip Day.

Leanne Simpson, Islands of Decolonial Love (Arbeiter Ring Publishing, 2013), 45.

Maggie Nelson, The Argonauts (Greywolf Press, 2015), 101–2.

Nellie Bowels, “Human Contact Is Now a Luxury Good,” New York Times, March 23, 2019 →.

Mandy Mayfield, “California Gov. Jerry Brown to protesters during climate speech: ‘Let’s put you in the ground,’” Washington Examiner, November 11, 2017 →.

“AMLO envía cartas a Felipe VI y al Papa Francisco: pide se disculpen por abusos cometidos en la Conquista,” Proceso, March 25, 2019 →.

Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 1–40.

Alain Badiou, In Praise of Love, trans. Peter Bush (The New Press, 2012), 53.

Tuck and Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor.”

Leanne Betamosake Simpson with Edna Manitowabi, “Theorizing Resurgence from within Nishnaabeg Thought,” in Centering Anishinaabeg Studies: Understanding the World through Stories, eds. Jill Doerfler, Niigaanwewidam James Sinclair and Heidi Kiiwetinepinesiik Stark (Michigan State University Press), 279–93.

cheyanne turions, “Woodland School: Kahatènhston tsi na’tetiátere ne Iotohrkó: wa tánon Iotohrha,” cheyanneturions.wordpress.com, January 16, 2017 →.

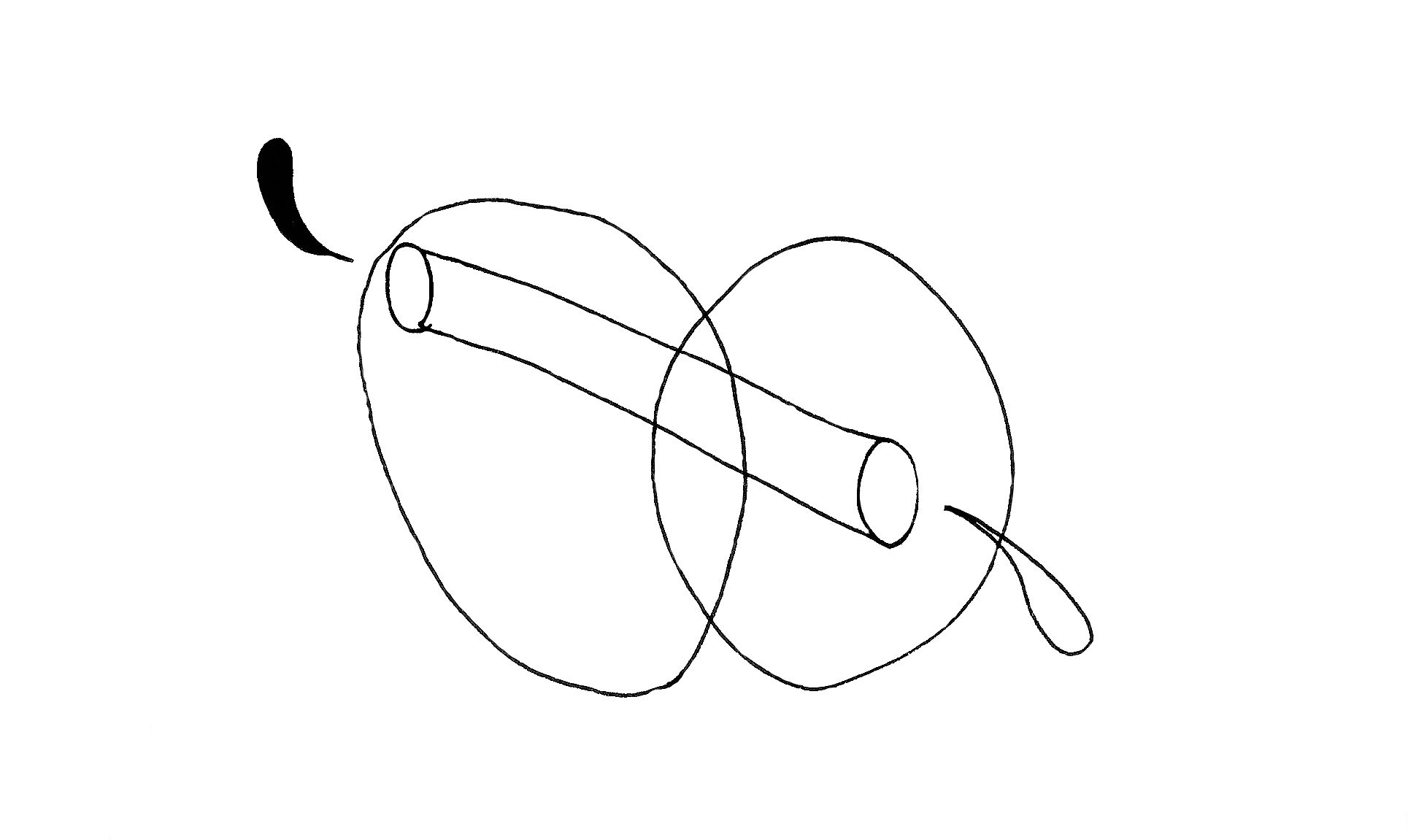

All paper and ink illustrations by Montserrat Pazos (2019).