Photo by Pyotr Nosov, USSR, 1980s

Keti Chukhrov: One of the weirdest things to observe in the recent opposition between pro-Western liberalisms and pro-Kremlin oligarchies was that leftist organizations and parties (even the left in the West), in their ardent confrontation with neoliberalism, were not sufficiently critical towards Putinism (Habermas, Chomsky). Interestingly, the oligarchies with their immense surplus wealth count as less unjust for a certain post-socialist or even Western left than law-abiding democracies.

Boris Groys: I do not think that Habermas or Chomsky have any sympathies with Putin’s regime. They are simply worried that the increasing confrontation between NATO and Russia could lead to a nuclear war. In this sense they just continue the politics of the Western peace movement from the period of the Cold War.

KCh: To my mind such a standpoint ignores the difference between the advantages of “democracy” (even with its hypocrisy and flaws) and the harsh forms of autocracy. Can we say that Western neoliberalism and the autocratic deviation of capitalism are merely two sides of the same coin, or are these social formations drastically different? I ask this question because sometimes the left, in their critique, envisages post-Soviet autocratic oligarchies as something conceptually less vicious than neoliberal capitalism. Whereas it is the other way around.

BG: The point is not capitalism but American domination of the contemporary global world. There is a certain anti-American ressentiment in many countries and political and cultural circles. One should not forget that all the countries that participated in World War I were capitalist countries. Capitalism creates a field of competition—and competition among countries often leads to war. Characteristically, the conflict between capitalist West and socialist East remained a cold conflict—because this conflict was an ideological conflict and not a real conflict of interests.

KCh: Yes indeed, yet certain leftists erroneously associate anti-American initiatives with anti-capitalism. Quite a considerable part of the unprivileged and oppressed layers of Russian society voted for Putin, and supported the war. Moreover, the so-called progressive wing of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (KPRF) supported the war with Ukraine. Might this be seen to a certain extent as the failure of the cultural left and intellectuals, who haven’t managed to produce a connection with the so-called “deeper people” (glubinny narod)?

BG: The movements that led to the end of Communism were nationalist movements. In all the former Soviet republics and Eastern European states, nationalism is an all-embracing ideology that unites the population of these states, from the right to the left. In all these countries there are small groups of intellectuals who still profess internationalism. But for the absolute majorities inside Eastern European nations, internationalism is associated with the Communist past—and, accordingly, is automatically rejected. That is true also for Russia. The KPRF is as nationalist as every other Russian political party.

KCh: You mentioned in a recent interview that the idea of “the Russian world” is incomprehensible and unconvincing, which is definitely true.1 Indeed, those who remember the evolution of Putin’s presidency can confirm that ideas like “sovereign democracy” and “liberal empire” were created by educated liberals who have worked as political technologists since the 2000s—Vladislav Surkov, Gleb Pavlovsky, Mikhail Remisov, even Stanislav Belkovsky and many participants in the Valdai Club. Suffice it to mention the recent notorious text by Timofey Sergeytsev.2 In that case, why do these “incomprehensible ideas” resonate with “the people”?

BG: Well, the Russian imperial government, as well as the Soviet leadership, were always afraid of nationalism, including Russian nationalism, because Russia consisted and still consists of many different ethnicities, religious communities, etc. Russia is an extremely heterogeneous country. Thus, any kind of nationalism presents a danger to its unity. At the same time, a certain form of nationalism is required to keep the Russian population united against dangers from abroad. So official Russian ideology tries to find formulas that are nationalistic and non-nationalistic at the same time. This is, yes, an impossible task. The attempts to fulfill it look awkward—and must fail.

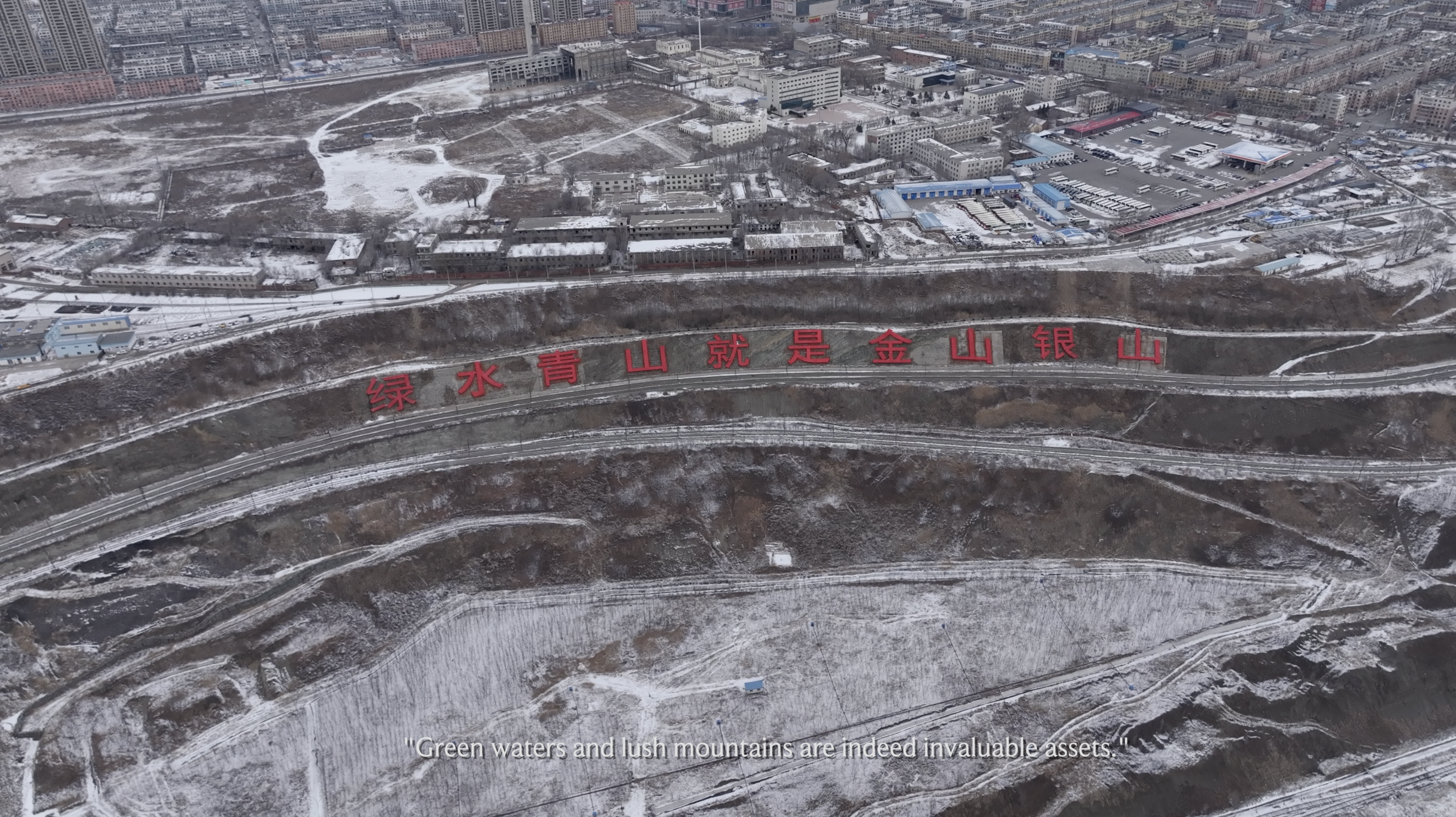

KCh: In recent explications of the war, certain pro-Kremlin analysts (e.g., Andrey Bezrukov3) have shifted from the rhetoric of “denazification” to “decolonization,” justifying the war as the liberation of Russia from its colonial dependence on the West. Allegedly, this is the result of consulting with Kremlin intellectuals, who try to inscribe Russian military policy—despite its aggressive character—within postcolonial discourse, making it side with the Global South. In this way, the war in Ukraine is claimed to be a “liberation” from pro-Western colonization, while the colonial appetites of the Russian Empire are, conveniently, not discussed. To my mind, ascribing the role of a classical “colony” to Russia is historically wrong. Even though Russia might have been provincial within the European context, it has never been the West’s colony in the sense that Latin America, India, or Africa have been.

BG: It seems to me that many people in Russia, including in artistic circles, experienced the 1990s as a time of the colonialization of Russia by the West, especially by the US. The decolonization discourse is a part of the discourse about overcoming the legacy of the nineties and the national humiliation that Russia allegedly experienced at that time. I could never understand this discourse but I can attest that I often heard it during my visits to Russia already in the nineties.

KCh: I was very much impressed by your book Philosophy of Care (Verso, 2022). Amidst the general tendency to treat care as an all-encompassing emancipatory framework for any cultural or social work, you make a distinction between being cared for as an object and the act of caring as a subject. You consequently emphasize that care can also be understood as subjugation, confining existence to the management of sickness, as you put it, from which the world has been subtracted. Could we say that contemporary democratic currents, even in their artistic and critical instantiations, are more a space for therapy than for vita activa?

BG: We are living in a society that privileges creativity, which is the production of new things. And this society considers care as an activity of low value because its goal is the maintenance of old things. Care has a low value because it is “unproductive.” But if institutions of care didn’t exist, the products of creativity would disappear soon after they emerged. Thus creativity would become impossible. Meanwhile, mankind has begun to better understand the role of care. Many people have started to care about nature, local cultures, etc.—all those things that can disappear if we do not care about them. Of course, such an extended society of care can be experienced as limiting our possibilities, and even as totalitarian, but, in fact, total care is impossible: at a certain moment old things die anyway and give way to new things.

One should also keep in mind that our relationship to institutions of care is contradictory. These institutions turn us all into patients and in this sense make us sick—even if we feel that we are healthy and full of energy. That is the reason for the resentment that people feel in relation to institutionalized care, including the protests against vaccination that we recently experienced in the case of Covid. On the other hand, these same people turn to medical institutions when they feel weak or unhealthy. So, for the mass of people, the feeling of being healthy is decisive. But this feeling can be deceptive.

KCh: Being quite skeptical about democratic institutions of care, you find the idea of public space insufficiently transformative or political. In fact, modernism and the avant-garde were critical of these institutions too, finding them homeostatic politically and artistically. Recall Adorno’s critique of the social and political agency of the middle class, and the standpoints of George Bataille and many other figures in radical art who were mistrustful of “public space.” This public dimension has more recently became crucial for thinkers like Chantal Mouffe in claiming the agency of the democratic “agon.”

In this context, how should we understand socialist societies of the post-avant-garde years—let’s say after the 1950s? How were the ethics of care organized in those societies? Were they organized as “care for the other” or as “self-care”?

BG: If we now speak about the application of care to living human beings, then of course, they are treated by the medical system as mere things—analogous to machines that have to be repaired in order to continue to function. And our bodies are such things, indeed. Our bodies are transcendent to us: we cannot see and investigate them from outside. We cannot know them. We can only “feel” them “from inside.” But this feeling does not give us any knowledge of them. Only medical institutions have this knowledge. Of course, physicians ask us from time to time, Do you have pain? How do you feel? We answer these questions—but only physicians are able to analyze and interpret our answers as “symptoms” of our condition. In this sense care by medical institutions is always a care by others.

In this respect Soviet institutions of care were not so different from other similar institutions. They applied to the bodies of patients some standardized medical knowledge that these patients could not have. At the same time, as in the case with all medical systems, it was the personal decision of the patient to appeal or not to appeal to medical institutions—one had to “feel unwell” and go to a doctor to start the process of medical examination and treatment. Of course, I mean here a “regular case”—not emergencies or catastrophes. And one should not forget that also in Soviet times one could find many alternatives to official medicine—healers with exceptional capabilities, yogis, traditional medicine using herbs of different kinds, etc. So one could decide what kind of treatment one preferred. Thus, the Soviet case was like any other case: a combination of self-care and institutional care.

KCh: You emphasize Heidegger’s view on the functionalization of production, which steals the existence of Dasein. However, if there were no infrastructure of production and if no one had organized economic distribution in the absence of a market, many people who lived under socialism would have remained homeless and hungry. They needed to be cared for in certain spheres of life. For example, peasants had to be cared for in terms of getting an education equal to that of higher social layers. When the demand bears on the common good, is it possible to remain in the sphere of self-care?

BG: Well, Heidegger looked at this problem not from the perspective of the common good but from the perspective of the individual Dasein. And Heidegger rejected the notion of life because to understand humans as “living beings” means to take an external position with respect to humanity and to put humans on the same level as animals and plants. Dasein cares not about its life but about its world.

It has angst that its world disappears. The disappearance of the world can mean that Dasein dies but it can also mean that Dasein loses its world and becomes a mere object in the world of others. In this sense, for Heidegger there is no ontological difference between death and becoming a patient of medical institutions. In both cases humans become mere things. In other words, the self-care that Dasein is practicing is also—and even primarily—directed against care by others, against institutions of care, against the biopolitical state that treats humans as animals.

However, as I indicate in the book, Heidegger shares the ideology of creativity. In his “The Origin of the Work of Art” he speaks, not unlike Nietzsche, about the impulse of energy given to the artist by Being, which is easy to associate with the energy of Life. And then Heidegger writes that creation presupposes preservation. He is skeptical, though, about museums, galleries, and other art institutions. He rather believes that this preservation must be done by the people to which the artist belongs. In other words, Heidegger is not interested in the education of humans, including peasants, but rather in their ability to manifest the experience of their Dasein.

KCh: You say that the person who cares for artworks in the museum—even without knowing what they are about—recalls the avant-garde artists’ expansion of care when they become bureaucrats of art production. In what way is this type of care different from democratic forms of care, which is “care for objects” instead of “care on behalf of subjects”?

BG: Art institutions are not necessarily democratic—art care, like care in general, is practiced by specialists. However, it is also true that the notion of art is permanently expanding and includes more and more objects that previously were considered “low” and thus unworthy of conservation. In this sense, one can indeed speak about the democratization of art.

KCh: In the latest theories of care understood as an emancipatory tool of democracy, one of the functions of care for others—the labor of care workers, underpaid nurses, even sex workers—is associated with freedom, as it is considered to have a noncapitalist, non-monetized attitude to those in need of it (see David Graeber). But there’s a paradox here: something that keeps one a patient is seen as emancipatory. Convalescence is treated as utopian.

BG: In modernity, care is practiced by care institutions. And care workers (even sex workers) are paid by these institutions, or else privately. The unpaid work of care was practiced mostly by women inside traditional families. But this is precisely what is now being increasingly abolished by the feminist movement. Traditional family structures are dissolving. Today one can expect only institutional care. And yes, of course, care workers should be paid much better.

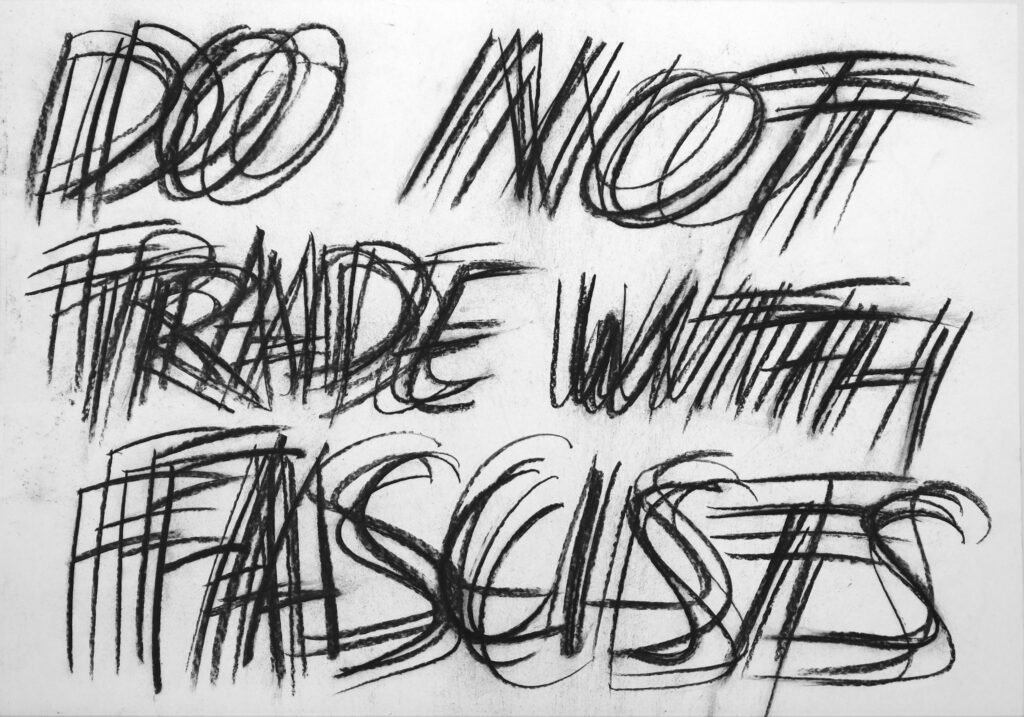

KCh: My last question is about the present documenta curated by ruangrupa. In the beginning my expectation was that the curatorial concept of the group would focus on explicitly non-Western practices, reshaping the art-as-institute with activities that come from rural or untranslatable non-modern frameworks. But as a matter of fact, lumbung activities do not differ from the protocols of socially engaged art and discussions; even the decision to publish theory in the newspaper for the homeless is a continuation of the strategy of documenta 14—“instead of uplifting the subaltern, let’s pretend to be them.”

BG: I think it is naive to expect that one can find in Indonesia some indigenous, “non-Western” art. Today the whole world is globalized, everybody has access to the internet, cities are growing, rural areas are becoming abandoned. And of course, everywhere the same questions are discussed. However, in different countries one finds different attitudes and perspectives on these questions, and one should be attentive to these differences.