The Iranian rock climber Elnaz Rekabi participating in the final of the Asian Climbing Championships in Seoul, October 16, 2022, wearing a black headband rather than a hijab. Rhea Kang/International Federation of Sport Climbing via AP.

This essay is part of an e-flux Notes series called The Contemporary Clinic, where psychoanalysts from around the world are asked to comment on the kinds of symptoms and therapeutic challenges that present themselves in their practices. What are the pathologies of today’s clinic? How are these intertwined with politics, economy, and culture? And how is psychoanalysis reacting to the new circumstances?

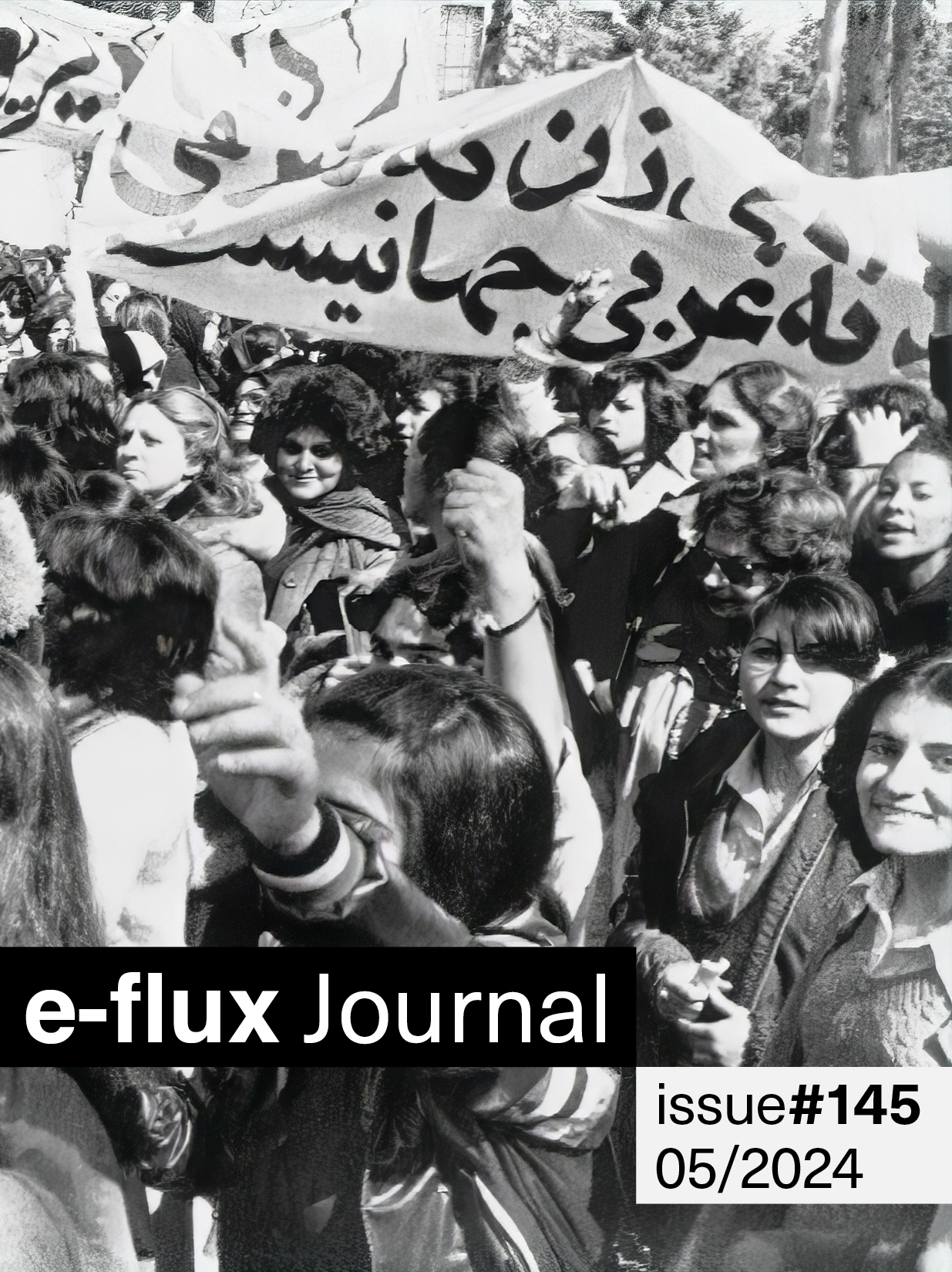

An ongoing series of protests and civil unrest began in Iran on September 16, 2022 as a reaction to the death of Mahsa Amini, after she was arrested by the morality police for wearing an improper hijab in violation of Iran’s mandatory hijab laws.

I believe that what we are observing in Iran, as I write this, is one of the most significant and subversive feminist movements of our times, and as Slavoj Žižek reminds us in a video message he sent to the Iranian people, it is not enough to support this uprising from a superior position. One must rather learn from it. This feminist movement is one that does not exclude; it does not exclude men, for in this geography it has become blatantly clear that the emancipation of men and women are inherently intertwined.

This subversive revolt is also not about identity politics; although Mahsa was Kurdish, it is not her Kurdishness that is emphasized. I think the Kurdish separatist movement in Iran has never before felt that they belonged with Iran and Iran with them. Now they have seen that if one of their daughters gets killed, everyone goes to the street, for she is a daughter of Persia. This movement does not exclude veiled women, although we hear less about that in Western media as it does not quite fit their mainstream narrative. Veiled women are included in this uprising, which is about an ethics of life; it is an invitation, a hospitable invitation towards cohabitation, towards finding a way to be with different parts of oneself and others. Various social classes and ethnicities are included in this uprising, which is mainly comprised of women, but clearly not just women, and it is not even age-specific, though it is predominantly composed of very young people, mostly born between 1995 and 2010, so-called Generation Z.

This subversive feminist revolt is the scene of the return of the repressed. We know from Freud that the repression of femininity is a remarkable feature of the psychic life of human beings, equally applicable to both sexes. We are observing the return of the repressed female body that refuses to be covered symbolically, and that says: face the fetishistic/phobic cause of your desire, and look at me, in my ordinariness, in my hunger for an ethics of women, life, and freedom. It is a hospitable invitation towards disturbance and an integration towards an ethics of life.

We have a myth in Iran written by Ferdousi in The Book of Kings, the main reference of Iranian mythology and one of the world’s longest epic poems. This particular story is that of Rudabeh and Zal. Rudabeh, Rapunzel-like, loosens her lovely locks of dark hair that cascade down her tower to Zal, her lover who climbs up the tower using not her hair but a rope in order not to hurt Rudabeh. Upon that lovers’ union a child is born, a baby boy named Rostam, who becomes the main epic hero of Iranian mythology, defending this land and helping it prosper with a sense of ethics, courage, and hospitality.

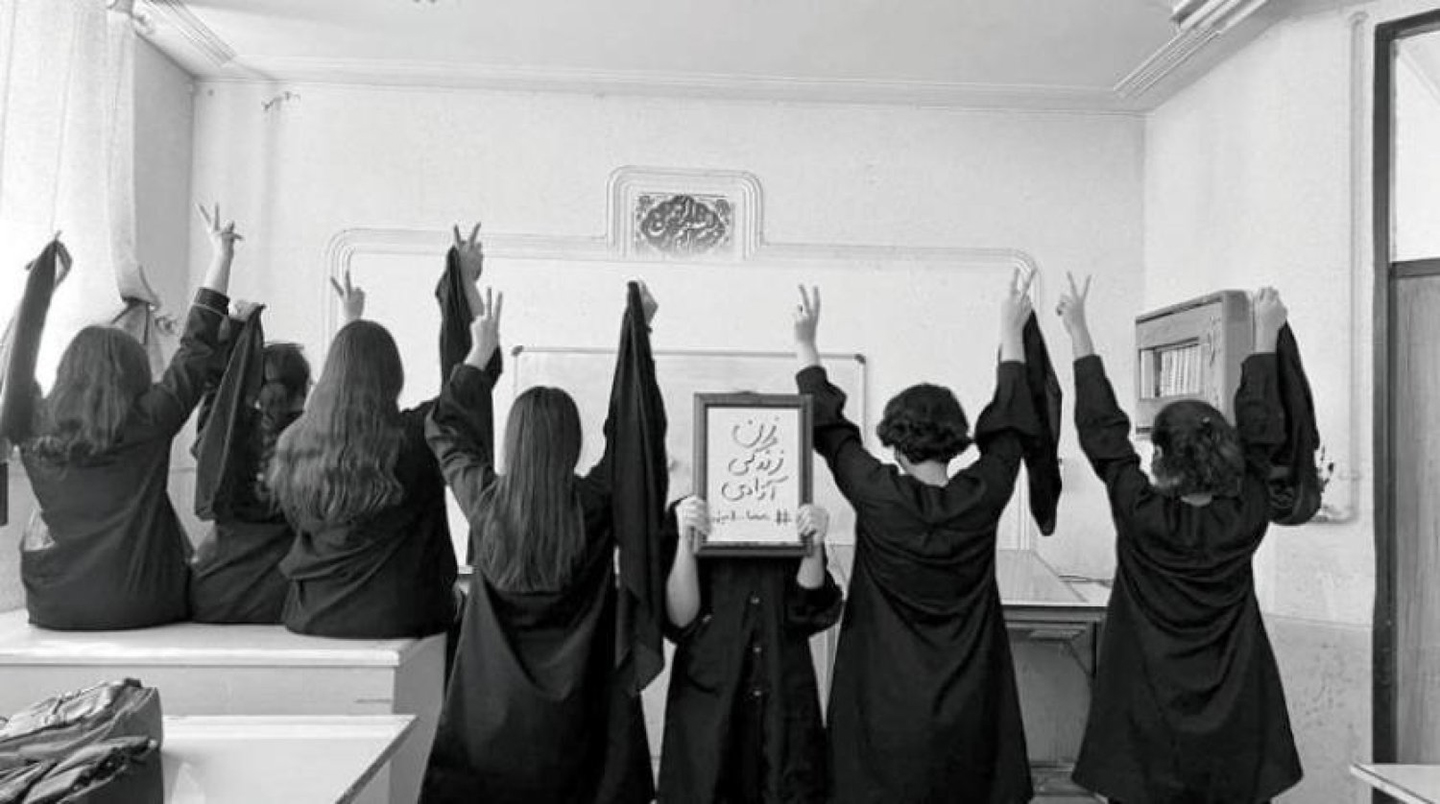

Can we attempt to retell this story as we do in psychoanalysis? Aren’t the daughters of Persia doing that exact retelling with the signifier of hair, more relevant than ever? I think the story they are retelling is the birth of Rudabeh’s daughter, who was never born. They are letting their hair down, and from this new union a baby girl is being born, one I have no right to name, one we must find a name for together—and we have to be careful, for we know the significance of names.

A new female epic hero is born. It is a birth that has been long overdue but years in the making. We know this well as psychoanalysts, that such a significant event doesn’t suddenly happen; rather, this event of the birth of a new subject is a process, and women have been the face of political resistance for years in Iran. We are observing the birth of Rudabeh’s daughter: she has let her hair down, and a new epic hero, a feminine epic hero is being born, one who is showing a sense of creativity, courage, resilience, and most importantly a hospitality towards cohabitation, which is part and parcel of “Thinking,” of the birth and becoming of a thinking subject. An event has happened and whatever happens now there will be a before and an after. Rudabeh’s daughter will transform this land and I look forward to her “becoming(s).”

This feminist revolution is subversive because it is disturbing various chains of significations: social, political, personal, public and private, external and internal, the very discourse of subjectivity. This revolt demonstrates that we are linked together and any movement in any geography that ignores this is bound to fail. This birth is about difference and not sameness; for we know as psychoanalysts that our need for sameness is the very death of the subject.

A fascinating aspect of this event is the new formation of groups. As Freud has magnificently elaborated in Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego, groups need leaders, but this new uprising in Iran shows that they are fed up with leaders in all their shapes and forms, for they are each a leader. There is a leader in every single one of them. They are also more intelligent together as opposed to each one of them separately—again the opposite of what Freud tells us and what we have known to be a fact of group formations throughout history. Hence we are observing the formation of a new structure of the group, as opposed to what has been previously witnessed. They are not impulsive, they are thoughtful, patient, and practical. We are observing an essential function of the life drive, the objectilizing function of the drive à la André Green, where the protesters are capable of transforming structures into objects, even when the object is no longer directly involved. In the very fabric of the saying “women, life, freedom,” there is a clear connection to life, binding, creativity, and sublimation. They are not saying we want to die for freedom, they are saying we want to live for freedom. Certainly at times there is a great price to be paid, we have seen that, but an attempt is being made to use the power of nonviolence, activity, and subjectivity, and choosing to tolerate passivity when necessary. We could go as far as to say that this is the only possible mode of an invitation for cohabitation, for thinking.

Are we not hearing even a possible remedy to the crisis of the Subject?

They want to live, they are not apologetic for their hunger, they don’t feel mad, bad or sad; this return of femininity, the return of the repressed is not here in a hysterical manner, it’s not here in a voyeuristic, exhibitionistic way, it is not here in the name of need but of desire. Rudabeh’s daughter is born and she is magnificent and I recommend we embrace her with a non-humanitarian hospitality, for she is wounded but has decided not to heal her wound but to display it, to inscribe it, and to name it. A new feminine epic hero is born and we can learn a great deal from her in your geography and mine. Let’s encounter her, for I guarantee this encounter will be transformative for all.

Maybe Rudabeh’s daughter, who will be Rostam’s sister, will aid her epic brother; side by side they will defend this land and help it prosper, not to its old glory but towards a new becoming, under the inevitable shadow of its ambivalent history. Maybe Rostam was in need of a feminine epic hero all along; maybe with the help of his sister he would not have unknowingly killed his son. Maybe Rudabeh’s daughter was needed all along, this feminine discourse of thinking was needed to prevent nonsensical and tragic killings. For the faith of Rostam, just like that of Oedipus, comes from the desire to know, though at times without the tools for thinking—the desire for remembering what they knew all along but could not face. A new epic hero is being born, a new feminine epic hero and whether we like it or not, this lovers’ union has happened. Rudabeh has put her hair down and we are hearing the screams of her daughter, who will transform this land and with the power of nonviolence oppose any authoritarian discourse, any authority that comes without responsibility and any responsibility that comes without authority.

I do not believe we have seen anything like this subversive feminist movement before. It has disturbed us in a revolutionary, magical, carnivalesque manner. The people who have taken to the streets are mourning together, celebrating together, and they want to dance, sing, and live. We are observing the magical resurrection of the witches. It is a fight for life not death; it is an ethics of life: the only possible psychoanalytic ethics. In the final analysis of love, away from the shadow of Antigone and her incestuous beginnings but inspired by her courage, this revolution in its singular collectivity marches not towards death but towards life. It is a feminine uprising not in the name of need but desire.

We saw you, we heard you, you disturbed us, you are the return of the repressed of the feminine, and the way you have come back is the way we never allowed ourselves to know you, to be hospitable to you, you are here to show us, to disorient us, you are the voice of the underground, of the carnival, of magic, and I am glad to have been alive at this moment and to have heard you, to have encountered you. You are glorious and you have forever changed the way women, social movements, femininity, bodies, uprisings, linkings, group formations, and hospitality are viewed. You have imagined and reformulated a new discourse of maternity, of the relationship between women in our geography and elsewhere. You have demonstrated an ethics of life, and of pleasure with all its inevitable troubles and disturbances.

You do not have to be here on the ground to be disturbed. Rudabeh’s daughters are born and in their singular collectivity they have disturbed you. From this geography that the International Psychoanalytic Association used to call “the rest of the world,” her daughters are heard all over the world, in my geography and in yours. This new epic heroine is not only born but she has said the unsayable, she has spoken, she has arrived, and what a welcome arrival it is. Let’s welcome her with our non-humanitarian hospitality, for her arrival encapsulates the resurrection of life, women, and freedom. Whatever happens now, nothing will be the same after, for an “event” has taken place. To start with, Iranian women will not be viewed solely as the victims of a patriarchal system nor will they be viewed as eroticized oriental objects. The daughters of Persia have spoken and shown the world that they are not only a lot more than that, but a plethora of archetypes that refuse to be spoken for. Rudabeh’s daughter is not representative of imprisoning binaries, she is a subject on the edge of desire.

Let me leave you with the image of Elnaz Rekabi, the Iranian rock-climbing champion who arrived a few nights ago in Tehran after appearing without her scarf in international competitions in South Korea. This was the first time since the Iranian revolution that a female athlete representing Iran broke the mandatory hijab laws. She was greeted by a huge crowd outside Tehran International Airport at 3:30 in the morning, to give her a hero’s welcome, with flowers and huge cheers for their newly arrived symbol of resistance. Yet another first in this uprising of many firsts.

There is no more perfect symbol of this uprising than the picture of our heroine rock climber, putting her hair down and disturbing yet another layer of signification by climbing up the tower herself, towards her own becoming.

Elnaz said in an interview with Iranian state television upon arrival that her hijab fell off “unintentionally.” Subsequently, Twitter was bombarded with people saying, “We love you, however intentional you get!” Welcome home Elnaz and keep on climbing.