Grigoriy Myasoyedov, The Road in the Rye, 1881

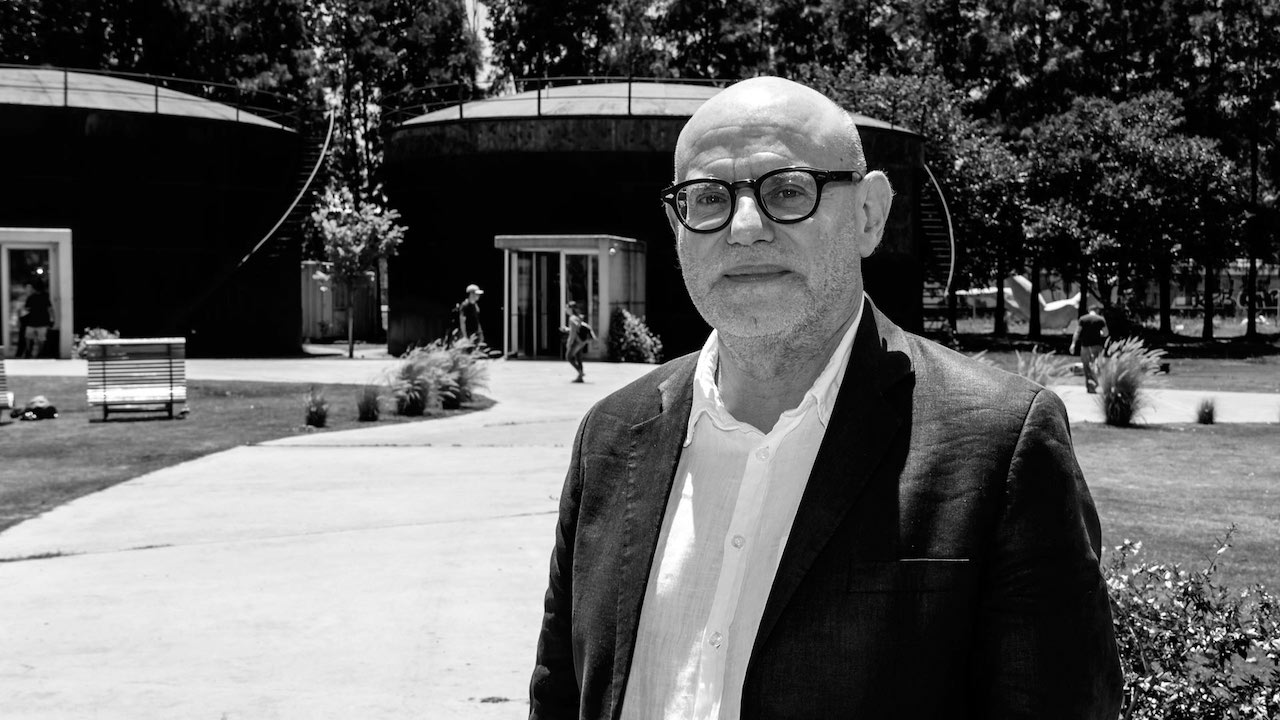

Boris Groys is a professor of Russian and Slavic studies at New York University, a philosopher, a cultural critic, and one of the world’s foremost thinkers on the nexus of art and politics. When his book The Total Art of Stalin was published, thirty-five years ago, it changed how we viewed the Soviet avant-garde and its relationship with the totalitarian regime by defining the state as an artwork produced with blood. Historian Sergei Bondarenko spoke with Groys about how the war in Ukraine will affect art and public thought and what awaits Russia after its defeat.

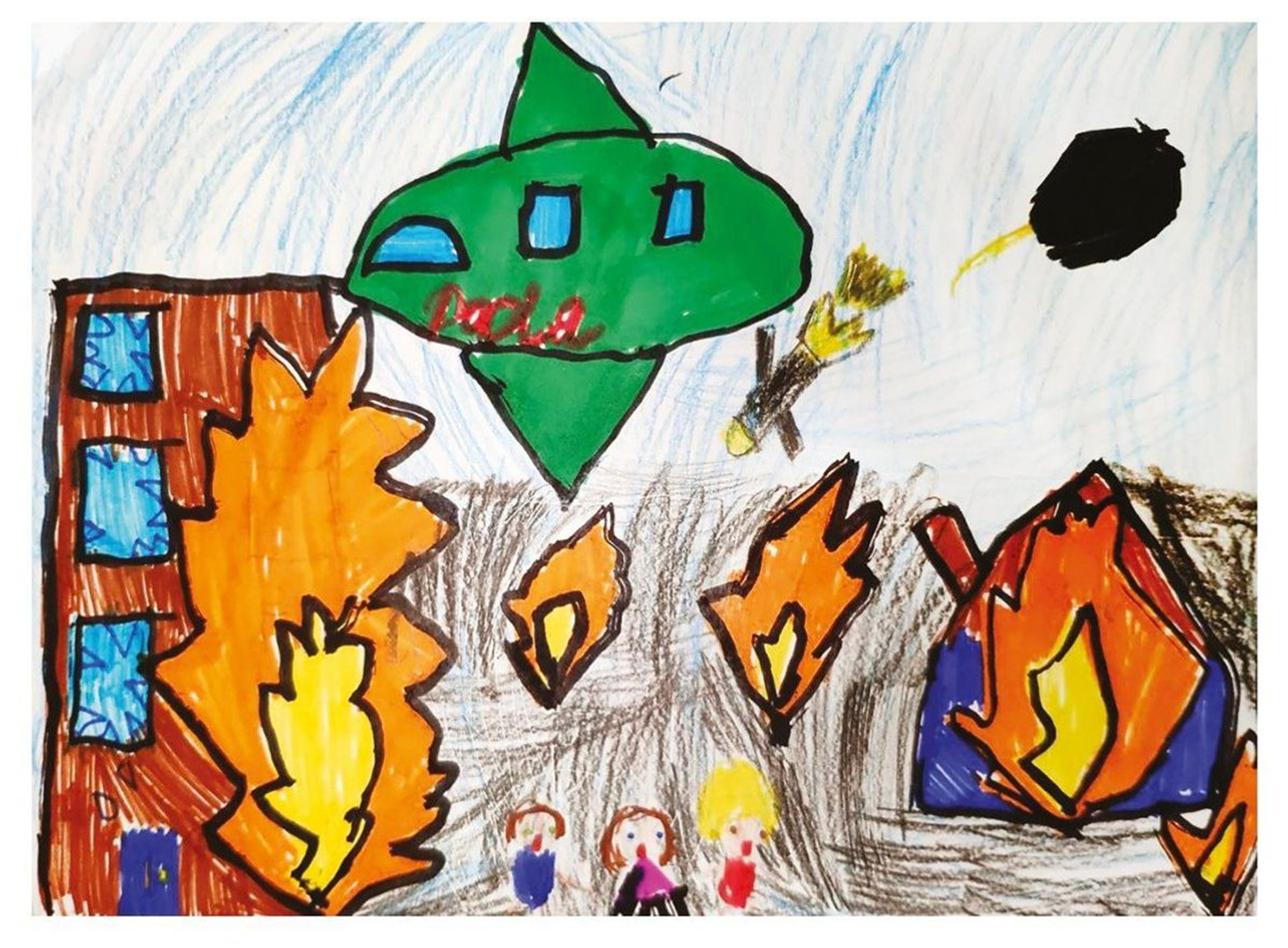

Sergei Bondarenko: How do you think art has been coping with the war? Is a new anti-war art now emerging?

Boris Groys: History shows that, in warring countries, art is usually heavily influenced by patriotic public sentiment. The same can be said about art during the First and Second World Wars. In these circumstances, anti-war art is practiced only in neutral countries, such as Switzerland. We might recall the French and German emigration to Switzerland during those wars, including writers such as Hermann Hesse, say, and artists of Dadaism and other avant-garde trends.

In the warring countries, anti-war art—in literature, primarily in poetry—emerged only after the war. For example, there were the novels of Hemingway, Remarque, and Céline, and, of course, German expressionism. And Picasso produced Guernica while in exile in France.

So, emigration is quite a good option for contemporary art in wartime. In emigration, you are not in a confrontation, in a situation of “for or against,” a confrontation which in warring countries only becomes radicalized over time.

SB: City streets have, seemingly, now become venues for anti-war art in the shape of graffiti, stickers, performances, and pickets.

BG: To repeat: I don’t think there is anything fundamentally new about this. Good old Malevich produced the Black Square as part of the production of the opera Victory Over the Sun, which was conceived as a mystery play on the Neva River in Petersburg. Khlebnikov said that the sun, unfortunately, did not go out—probably because the Neva does not possess sacred power. Maybe it would have worked on the Nile. The futurists did demonstrations and happenings on Petersburg’s main drag, Nevsky Prospekt, while the Cabaret Voltaire of the Dadaists, organized by Hugo Ball in Zurich, was also a public space. If you imagine, for example, that classical formalism was any different in this respect, think again. Kandinsky dreamed all his life of working in the theater and staging an opera. He wrote the theatrical piece Yellow Sound and began producing it in 1914. None other than Ball served as his assistant. Again, only the war prevented them from finishing it.

So no, the city has long been a space for art. Marinetti rated the efficacy of his performances by the number of mentions they garnered in the morning newspapers. Artists have always appealed to public space. Yes, the mass media have changed, but the principle itself has not. Only the amplification and signal propagation have been ramped up.

SB: How has the ongoing mobilization in Russia affected all these processes?

BG: I don’t see a genuine psychological mobilization of the Russian populace. The country has formally been mobilized, but a large percentage of people are living their ordinary lives. However, the rationale of war always consists in ratcheting up mobilization, including the psychological equivalent.

I once talked to an extremely elderly lady who told me how she was once riding a tram on Petersburg’s Petrograd Side (I also rode the same tram: the tram routes in Petersburg are quite stable) when she suddenly saw that someone was giving a speech from the balcony of the ballerina Mathilde Kschessinska’s mansion. She thought about getting off and going over to have a listen but decided she had more important things to do and stayed on the tram. Of course, that person on the balcony was Lenin. But the thing is that, at the time, even a person passing by on a tram could have failed to notice him. A year passed, then another year—and the situation changed radically. Mobilization also becomes more visible over time.

SB: Is this inertia?

BG: People’s reactions change gradually. This can be researched sociologically. Psychologically, however, we feel this change as it manifests itself more and more. That is art’s role, if you will. Psychological processes are difficult to describe objectively, so only when a war is ending does art take on this function of describing people’s personal psychological reactions. And not just isolated reactions, but typical, more or less common, reactions.

I remember quite well how the Soviet and Western populaces were mobilized differently during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Almost no one paid attention to it in the Soviet Union, and I noticed it only because I regularly read foreign newspapers and listened to foreign radio. In America, half of the population began building bunkers for themselves. The socio-psychological differences between the West and the East are quite great. The Western psyche is highly unstable: it gets terrified and mobilizes very quickly. Nietzsche nicely described this state of constant terror, the feeling that everything is now on the verge of collapse. This feeling still does not exist in Russia. In this sense, it is gradually, quite slowly becoming a Western country.

SB: I wanted to ask you about the psychological experience of artists working under duress. You lived among such artists in the 1970s. Is it possible to somehow compare their experience with what people in Russia who oppose the war are experiencing now?

BG: After Stalin’s death, many Soviet artists believed it was possible to insinuate the modernist tradition into local culture and affirm individual artistic freedom. They had such examples before their eyes: in Poland, Hungary, and Yugoslavia, this had meshed quite well with a certain type of provisionally socialist political regime.

By the early 1970s, when I myself was already quite heavily involved in this art scene, all the people I knew were utterly disappointed: their hopes had been crushed. I must say that I hadn’t entertained any such hopes. I took the disappointment of expectations for granted—I just didn’t pay it any mind. The people who worked [in art] in the 1970s and early 1980s reacted to this disappointment by creating their own independent world. The press and public life were under the state’s control, but its control over everyday life and private life was rather flabby.

It was a period when there was a loss of social gravitation. A realm of fairly independent artistic activity was created, but I don’t think this situation will happen again. The pressure from the regime had weakened, while market pressures had not yet arisen. By the mid-1980s, however, it had become clear that there was a big difference between people who had money and those who didn’t have it. This gave rise to a lot of pressure: either you competed on the market, or you simply perished. But the 1970s were a period when, in fact, no pressure—neither ideological nor economic—was exerted on Soviet individuals.

The level of economic pressure on the individual is now quite high in Russia. When I read Russian articles here in the West in the early 1990s to the effect that freedom would increase there with capitalism’s advent, I was very surprised, to put it mildly. With the growth of capitalism, people begin to fear for their money. And if you don’t stay in the fairway, you will sure as hell lose money. I think that, in Russia, the link between prosperity and traveling in the fairway is the main transmission belt that keeps society functioning.

The creation of alternative structures is possible under these circumstances, but it is less likely than it was in the 1970s, when people lived amid the informal culture and, importantly, the informal economy. It was this that kept people from hitting rock bottom. I now have the impression that, as things go on, it will be less and less able to keep them afloat. While the mainstream, the drive belts linking economic well-being and public loyalty will only intensify.

SB: This past summer, you argued that Russia’s purpose in the war was to isolate itself, to cut itself off from the West. What will happen to culture and cultural institutions? Will they be able to restore informal ties with the outside world? Or will there really be a rupture, a comprehensive internal restructuring?

BG: This is quite difficult to foresee. But I will say this. Even back in the early 1990s, when I would go to Russia to give lectures, I would see the local progressive scene, and people from it would very often say to me, “What is this Western art to us? We have our own context.” They had already taken a defensive position against the West at that time. They saw the West as a colonial force that imposed its own criteria and points system. The defense mechanisms emerged immediately: it was already noticeable during perestroika, during the Soviet Union’s final years. So, I am of two minds about the current situation. Yes, it’s a pity that ties are being broken. But I think that they are being broken not only because the official policy has gone in this direction. These defense mechanisms, which have always operated, basically, have simply intensified. And they will continue to intensify, it seems to me.

Many people—consciously, subconsciously, semi-consciously—savor the feeling of isolation. For a long time, they were annoyed that success in Russia was largely measured in terms of success in the West. The colonial nature of Russian culture thus made itself felt. Now that has gone. Success in the West is impossible. Success in Russia is the only criterion left. And I think this satisfies many people, even if they wouldn’t admit it.

We will understand this period of Russian history only when it is over. It will be over in a couple of years—that is understood. It won’t last long. When that happens, we shall see which people in Russia made money off the departure of Western companies from the country and how much they made. The West mainly regards this departure as a blow to the Russian economy. But on the inside, it seems to me, it is regarded as a chance to redistribute property in their favor. Isolation has given rise to many people who have a stake in it. And it is not just the state—it is private interests too.

SB: It seems that this is just one of many examples of how the same situation is evaluated differently in Russia and in the West.

BG: In Europe and the West as a whole, the principal confrontation is between globalism and nationalism. Western society is split between those for whom globalization is an opportunity and those for whom it is a threat. In this sense, the United States is maybe even more divided than other countries. We will see the same split in Russia, where it will be formulated even more clearly. It will be a split between people who want to reglobalize Russia and those who want to make money and be successful in a deglobalized Russia.

This is a period of war. War has its own rationale that dictates when it ends. We know that wars end when both sides are exhausted. Russia now thinks that the West will be worn out sooner. The West thinks the same thing about Russia. In this scenario, the war will continue. But when everyone finally realizes that they are exhausted, the war will end. There will be a change of regime in Russia afterwards, because Russian regimes cannot survive after losing wars. And the war is already lost. It’s a matter of a couple of years.

SB: What do you make of the anti-globalist rhetoric employed by Russian officials? About their desire to lead some anti-Western coalition while simultaneously affirming Russia’s own “national” mode of existence?

BG: In America, this is not part of the discussion about Russia at all. Russia is seen here as a weak country that tries to take more than befits its rank and as such is dangerous. How it attempts to justify overstepping its rank is of no interest to anyone here. How do you explain that someone has more claims and grievances than actual capabilities?

As for your question about colonialism, it makes sense. I am currently writing an article about Russian imperialism and have been reading many real Eurasianist thinkers, who were writing in the early twentieth century, including Nikolai Trubetskoy, who was just a very good writer, unlike all the rest. Trubetskoy already had this idea that Russia should head the world anti-imperialist movement. The Eurasians of the 1920s also opposed the New Economic Policy (NEP). All of them argued that it would lead to Russia’s economic occupation by the west. They thought that political and cultural autonomy was the most important thing.

When people talk about Russia’s “special path,” they often overlook the fact that it already made its own special choice in the political sense—it chose communism. We should not forget that the Western countries somehow or another chose fascism. So, while the West has been negotiating fascism, Russia is now negotiating communism. These two processes are completely different. In Europe, nationalism is marked negatively [by the liberal majority]: it is associated with fascism. Throughout Eastern Europe, nationalism is positively marked because it represents resistance to communism. These two different markings of nationalism are the source of many ambiguities and much confusion in contemporary politics. When people here in the West talk about nationalism, they remember Hitler. In the East, when they say “nationalism,” they recall the heroic resistance to the KGB.

SB: It’s emancipatory nationalism.

BG: Yes, but not only. It is nationalism versus communism. That is, nationalism versus internationalism and cosmopolitanism. Which means that Eastern European nationalism in all its shapes is on the right of the political spectrum in Western terms. Note that there is no essential difference between communists, socialists, and liberals in the West; they, in fact, have merged into a single party. In America, they are just “the left,” and they cover the entire spectrum of globalist attitudes from liberal to communist. While “the right” consists of essentially anti-globalist parties, in which many people immediately see shades of Hitler. There is no such situation in Eastern Europe. There, too, liberal globalism is regarded as something like communism, which must be combated in the name of nationalism. This is clearly visible in Poland and Hungary.

There is a certain ideological ambiguity in Russia in this context. Russia, as you correctly say, is always trying to “lead.” The desire to “lead” is always a liberal/communist desire. In the modern world, the idea of “leading” always pulls you to the left. Two desires collide in Russia: “separating” (pulling it to the right) and “leading” (pulling it to the left).

SB: Maybe it should break away—thereby setting an example—and then lead those who subsequently break away.

BG: Yes, first separate, then lead. Like Lenin back in the day: he broke away from social democracy, and later took charge of the Revolution. The problem is that only the first part has been done—Russia has “separated.” I think that there will be no turning back even when peace comes. Russia has separated forever. It will be possible to make contacts, but nothing more. It will certainly not be possible to “lead.” The world has changed a lot, and Russia cannot lead anything. Future Russian politics will be quite traditionally split between those who will be glad to have separated and those who still aspire to “lead” something bigger. These will be the two poles of Russian cultural politics after the war. But right now, we are still far from that. We are not at that point yet. We can discuss this now because I am in New York, and you are in Berlin.

SB: It’s the classic setup.

BG: Yes, it’s the classic setup, and it should not be underestimated. When we now look back at the twentieth century, we see that very many things were evaluated, discussed, and identified in the emigration, outside of Russia itself. So, I don’t know. It seems to me that the situation is really extraordinary now, and if we speak from the position of a frightened Westerner, one had better not stick one’s nose in an extraordinary situation.

Originally published in Russian as “Two Desires Collide in Russia: Separating and Leading,” Holod, December 12, 2022. Translated by Thomas H. Campbell.