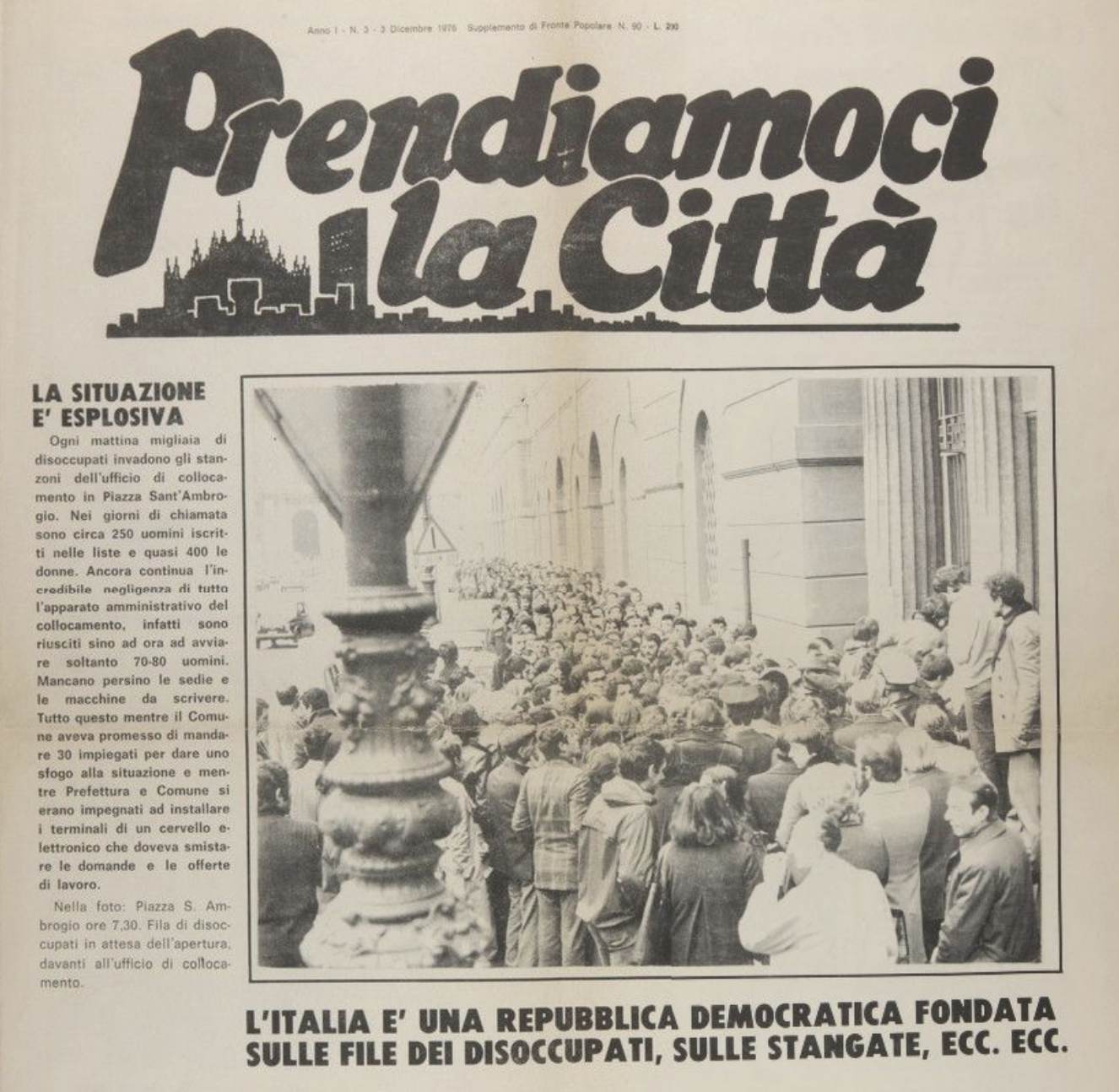

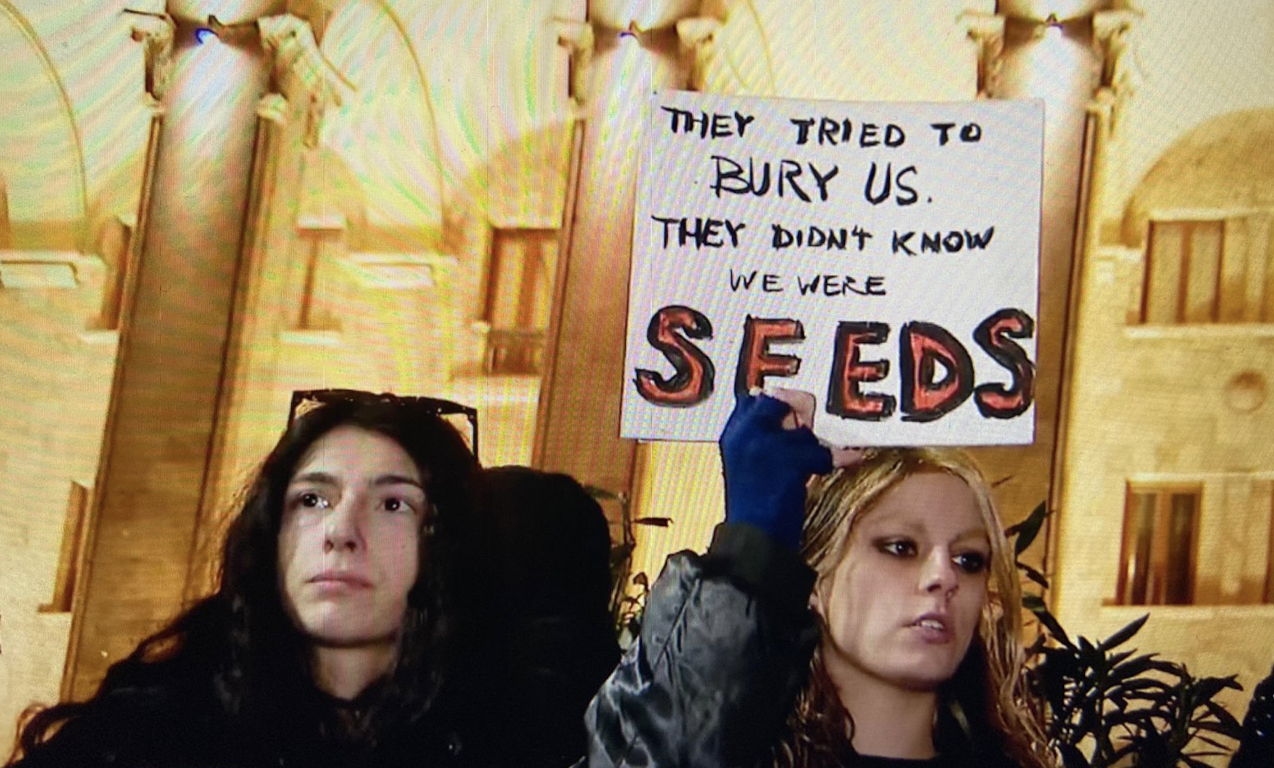

Protesters in Tbilisi, Georgia, March 2023

The Political Background of the March 7–9 Protests

When, in 2012, the Georgian Dream party, headed by the oligarch Bidzina Ivanishvili, took over from the United National Movement (UNM) founded by Mikheil Saakashvili, it was already clear to some that pro-Kremlin forces had won in Georgia. I was among those few. Yet too many people, including former Soviet and post-Soviet shadow businessmen—“thieves in law” who were influential in Eduard Shevardnadze’s time and who returned to Georgia from exile after the victory of Ivanishvili—supported this change. The grassroots electorate voted for Ivanishvili too, because Saakashvili’s policy of accelerating the construction of “Western democracy” and “civilized sociality” in Georgia—with its transparent economic and civil institutions that had to cut ties with the Soviet regime, including with politicians and intellectuals involved in the post-Soviet government of Shevardnadze—scared away a considerable part of the population. As for the pro-Western intelligentsia, which also voted against Saakashvili, their reason was that they had reservations about his dirigisme and meritocratic strategy. This strategy focused on excellence in education, political management, and social production—a stance that could not integrate all layers of society into a program to rapidly catch up with the “civilized” liberal democratic West.

Moreover, in some post-Soviet countries corruption has often been considered a more humane way to govern the impoverished layers of society. It’s cheaper to donate through charity or bribe the police than comply with the requirements of transparency in taxation, allowances, and payments. Indeed, it is a paradox that in post-Soviet societies, populist support for conservative values or mild corruption is often seen as more democratic than the work of legitimate democratic institutions. This is the reason why, similar to the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, which supports most of the decisions of the Kremlin, the Georgian post-Soviet left is often more inclined to side with oligarchic autocracies than pro-Western liberal democratic governments. Therefore it’s no surprise that during Saakashvili’s presidency, a considerable part of society, regarded as unskillful or unreliable, was either removed from active social construction or unable to access meritocratic social uplift.

It is important to know that corruption and kleptocracy in post-Soviet states persists not only through voluntary adherence; with the institutional system regarded as beyond reform, this shadow logic—both in the sphere of the economy and in political rhetoric—often becomes the only viable method to distribute resources and opportunities. For example, in December 2021 the Georgian government, unofficially ruled by pro-Kremlin oligarch Bidzina Ivanishvili, did not accept a financial contribution from the EU of 250 million euros simply because the government had not provided an account of a previous tranche and failed to prepare for the distribution of the new donation. Such systems embezzle money because they do not have the levers to properly utilize and invest it. Georgia has yet to confirm its adherence to the twelve points required for EU candidacy (which Ukraine and Moldova already confirmed). Ivanishvili’s government not only lacks the will but also the skills and systemic levers to implement the necessary reforms. The twelve compulsory steps for EU candidacy are the following: to avoid political polarization, guarantee the functioning of independent institutions, reform the judiciary system to make it independent, strengthen anti-corruption agencies, implement de-oligarchization, protect the human rights of vulnerable groups, enhance gender equality, involve civil society in decision-making, and incorporate European Union Human Rights judgments into Georgian courts. The recent policies of the Georgian Dream party move in the opposite direction: they discriminate against gender minorities, safeguard Ivanishvili’s oligarchic clan, destroy independent institutions, and manipulate court decisions.1

The biggest mistake of the Saakashvili government was to exceed its punitive authority in relation to post-Soviet corruption and criminal activity. This is why Georgian citizens belonging to the previous shadow infrastructure—or affiliated with it in some way—have persistently refused to support the UNM. Although capitalism is associated with liberal democracy and the free market, the systemic shift from the dismantled Soviet economic system to the globalized capitalist one would require unpopular measures, such as getting rid of the former Soviet bureaucracy and intelligentsia and reining in financial corruption. Saakashvili and his government publicly acknowledged their mistakes and apologized for them after their electoral defeat in 2012.

Soon after the elections it became clear that not only was Georgian Dream failing to fulfill its own policy promises; it was also rapidly dismantling the civil institutions built by the Saakashvili government between 2003 and 2012. In the 2018 election there was no winner in the first round; the head of the UNM, Grigol Vashadze, and Ivanishvili’s protégé, Salome Zourabichvili, faced each other in the second round. The results were falsified in favor of Zourabichvili. This is when the political crisis starts in Georgia: since 2018 the majority of Georgian citizens have voted against Georgian Dream, the party in the pocket of Ivanishvili.

Ivanishvili’s sympathies for the Kremlin, although they are evident, should not be overestimated. It is clear that billionaire Ivanishvili needs to protect his property, which he partly sold and “laundered” before running for the presidency. Yet the reason for his subservience to the Kremlin is not only his Gazprom shares, which many assume he still holds; nor is it his ownership of Georgian businesses oriented towards Russia. Rather, he may have received the same instruction from Moscow as Badri Patarkatsishvili, a Georgian oligarch who allegedly ran for president in 2008 at Moscow’s behest. Patarkatsishvili lost the election and mysteriously died a few days later. Ivanishvili, on the other hand, managed to win his election in 2012. This was to a considerable extent due to the fact that Kremlin was said to have invested up to a billion dollars to defame Saakashvili and his government.

A Brief History of Recent Georgian Protests

Starting in 2019, the following events in Georgia led up to the current protests against the proposed Law on Transparency of Foreign Influence:

1. So-called “Gavrilov’s night” (June 20, 2019), when MP Elene Khoshtaria (Droa party) disputed the invitation of Sergei Gavrilov, a member of the Russian Duma, to Georgia’s parliament. Gavrilov is a pro-Kremlin member of the Russian Communist Party. Khoshtaria’s intervention was followed by fierce protests, during which the government used rubber bullets against protesters.

2. The raiding of Rustavi 2, a TV channel representing the opposition. Afterwards, the channel’s head, Nika Gvaramia, founded Mtavari TV.

3. In the November 2020 parliamentary elections, Georgian Dream falsified its votes to receive 43 percent support. After this, the coalition of opposition parties announced a boycott of parliament, but when other opposition MPs and smaller parties started to gradually return to parliament, the boycott lost its force and dissolved.

4. On July 5, 2021, anti-LGBTQ gangs, instigated by the government, attacked the organizers of the Pride parade. Later, on July 11, a rally against the cancellation of the Pride parade ended with fifty journalists injured, including serious injuries to Lekso Lashkarava, a TV-Pirveli cameraman, which led to his death.

5. Saakashvili returned to Georgia on October 1, 2021 and was immediately arrested. On October 14, fifty thousand people rallied in support of him.

6. Nika Gvaramia, the head of Mtavari TV, was arrested in May 2022.

7. Sixty thousand people rallied in the support of Georgia’s EU membership on June, 20, 2022.

8. In December 2022, an international council of independent physicians confirmation the poisoning of Saakashvili. In the same month, a Hague court acquitted Saakashvili of initiating military actions in South Ossetia during the war in 2008, and a rally was held in the support of his temporary release for medical treatment. President Salome Zourabichvili denied pardons to Saakashvili and Gvaramia.

Those who participated in these protests felt exhaustion and apathy after their failure, and hoped that every new attempt would bring about a better result. What was disappointing about these previous protests was that while they started with a unified opposition and a readiness to fight to the end, this fervor soon faded or devolved into internal disputes. The government used these cracks to dismantle the unity of the opposition. According to some unconfirmed reports, certain opposition leaders might even have been bribed by Ivanishvili to either leave their parties or give up the boycott against parliament. The two most destructive moves within the opposition after 2018 were: 1) the hesitation of smaller parties to consolidate around the biggest opposition party (the UNM, with its 25 percent of votes), which undermined the initially unified decision of the opposition coalition to boycott parliament in 2020; and 2) the inability of the opposition to rally around the release of Saakashvili to facilitate his recovery after the poisoning.

As Mtavari TV presenter Nanuka Zhorzholiani has claimed, people did not show sufficient enthusiasm to liberate Saakashvili. UNM leaders were reluctant to do so for various reasons. Although Saakashvili himself was disappointed by such reluctance, he never mentioned his discontent publicly, knowing the political crisis that Georgia was facing. Indeed, Nika Melia, the former head of the UNM party—which was recently taken over by Levan Khabeishvili after an internal party election—was blamed by supporters for his insufficient efforts to free Saakashvili. According to Zhorzholiani, the rally for Saakashvili’s liberation that she personally coordinated with Saakashvili was not financially supported by the party or attended by party members.

This is to say that starting in 2018, oscillations between the necessity to mobilize and the subsequent withering of this necessity were exhausting for Georgian civil society. Indeed, during my last visit to Tbilisi in September 2022, I could not help feeling some opportunistic consensus in the air: until liberal values and tolerant relations with the democratic West come about, more explicit solidarity with Ukraine, the liberation of political prisoners, and the resignation of the pro-Kremlin government can be indefinitely postponed. Many tacitly believe that it’s more profitable to stay in the gray zone between Russia and the EU, without making any explicit decision, because this would require too many political, social, economic, and emotional transformations. This turns the rhetoric of resistance into a process without results, where the opposition and its public allies are satisfied by the process alone without any real consequences. As Nika Gvaramia, now a political prisoner, said in an interview with Tavisupleba radio: “Unlike classical dictatorships, contemporary autocrats, instead of forcefully suppressing protests, which creates the potential for resistance in response, tactically aim for the protest’s evaporation, its emotional exhaustion.”2

The cultural middle class and students have mostly stayed away from the main political parties and their conflict, declaring that they are neither with Georgian Dream nor with the UNM. Young people who have joined the protests since 2018 have demanded not to be allied with any party, be it governmental or oppositional. (Unfortunately, such neutrality only helps Ivanishvili.)

Two tactical moves made by Ivanishvili turned out to be quite successful: 1) before February 24, 2022, Georgian Dream sought to demonize Saakashvili’s nine years in power; 2) after February 24, Georgia’s straying from the European path and reluctance to fully support Ukraine were justified by the menace of a second Russian front, this one on Georgian territory. Georgian Dream was sure that the protests against the foreign influence law would end up like previous protests, the initial fervor fading into mild resistance. With the fatigue of the opposition, the tensions within the UNM, and general political apathy in society, Georgian Dream thought it was a good moment to introduce the law, which was a copy of one passed in Russia. The law facilitates the stigmatization and exclusion of the majority of critical media, journalists, NGOs, and noncommercial or cultural institutions. If the law had been passed, things wouldn’t have gotten as bad as they are is Russia now, but Ivanishvili and Georgian Dream allegedly needed the law in order to get rid of critical media and Western NGOs before the 2024 elections. In addition, the law would have appeased Georgia’s Kremlin benefactors.

Meanwhile, the pro-Western democratic coalition faces a problem. In the political arena, its opposition to the autocratic, post-socialist, corrupt government is quite evident. But in daily life, in the realms of consumption and ownership, in the distribution of wealth and privileges, the pro-Westerners and the autocrats are not so opposed: there is a kind of tacit agreement between them about mutual profits. This is because neither of these political factions is fully faithful to their credos. The autocrats, who stand for the church and traditional values, educate their children in the West. The children of numerous anti-Western MPs were born either in the EU or the US, with the aim of gaining citizenship in those countries. Many of these MPs even own property abroad. This means that the autocrats wield repressive governing mechanisms for purely instrumental reasons—in order to keep the population in the grip of religious, statist, and conservative beliefs, since this guarantees their predictability in the voting booth. Likewise, the democratic pro-EU opposition and their electorate criticize the autocratic pro-Kremlin government and demand the liberation of political prisoners. But when it comes to concrete—judicial, social, media-based—acts, they dither, since such acts threaten their comfort and lifestyle. In a small society where politicians on opposite sides of the barricades are often descendants of families that are friendly to each other, or even distant relatives, or are intertwined in business, the radical splitting of nepotist bonds is very difficult. I was often surprised to find that numerous arts and culture officials who claim to critique the autocratic government collaborate with Georgian Dream media. The situation is even worse in the realm of commerce: it’s difficult to boycott Ivanishvili when the country’s food and medical supplies, or digital infrastructure and even natural resources, are mostly in his hands.

The Fate of Georgian Presidents No. 1 and No. 3

Saakashvili, along with the former prime minister Zurab Zhvania and the first president Zviad Gamsakhurdia, is one of the few Georgian politicians who coherently followed his declared platform and convictions. He set out to build a post-socialist capitalist democracy in a newly established nation-state, to make Georgia a member of NATO, and to follow a pro-EU path. This would first and foremost mean bidding farewell to shadow businesses and money laundering, implying the eradication of corrupt arrangements and gray economic zones and the disempowerment of former elites. However, Georgian society, which for years manifested a desire for Western-style capitalism, proved to be unprepared for such a full-fledged transformation—not only in the early 1990s during the presidency of Zviad Gamsakhurdia, but also during the presidency of Saakashvili, to say nothing of the present socioeconomic situation. The biggest difference between the Western and the post-Soviet progressive intelligentsias after 1989 was that left-liberal Western intellectuals did not support capitalism even when they did not explicitly side with social democracy, whereas post-Soviet intellectuals, with few exceptions, believed anti-capitalist discourse was associated with the socialist past and was therefore unviable.

According to prominent social historians Zaal Andronikashvili and Giorgi Maisuradze, the main feature of late-socialist and post-socialist Georgian society was homeostasis. It aspired to freedom of speech and open elections, but the establishment of legal transparency, civil equality, and economic accountability, and the cutting of business ties with Russia, were tacitly rejected by the early post-Soviet Georgian elite.3 In 1991–92, the Georgian intelligentsia supported the coup d’état in which former Communist Party general secretary and foreign affairs minister of the USSR Eduard Shevardnadze took power instead of Zviad Gamsakhurdia, without waiting for the next election. Back then, Gamsakhurdia had wide support across the country, but the so-called “red” intelligentsia preferred to retain the late-Soviet-style shadow social infrastructure rather than follow the path of systemic transformation. Part of the Georgian intelligentsia then participated in getting rid of Gamsakhurdia by means of a coup led by the informal military squadrons of Jaba Ioseliani and Tengiz Kitovani, and supported by the former mafia, with Shevardnadze bringing in Russian troops to assist. Whether the post-Soviet institutional transformations were properly implemented by Gamsakhurdia is another issue; what is clear, however, is that there would have been no war between Georgia and Abkhazia if Gamsakhurdia had remained in power and if Shevardnadze had not sent his semi-legal troops to western Georgia and Abkhazia to punish Gamsakhurdia’s supporters.4

Saakashvili attempted to overcome this homeostasis, whereby Georgia assures the West that it aspires to join its orbit while simultaneously convincing Russia that it will remain within its zone of influence. Shevardnadze was a virtuoso in such double-bind tactics, which proved to be ineffective; neutrality didn’t prevent him from ultimately falling from grace with the Kremlin. The nine years of Saakashvili’s administration confirmed that once the socialist system was rejected, building an efficient capitalist system required moving towards the democratic West without equivocation. There’s simply no third way in real politics after the demise of historical socialism: the choice is between Western democratic capitalism or autocratic, corrupt, feudal quasi-capitalism.

With the UNM in government, Georgia was considered one of the most successful cases of exiting the Soviet system with stable institutions and a relatively transparent economy. However, there were officials in the West who demanded softer measures from Saakashvili’s government. Until February 24, 2022, certain figures in the EU were even content with the return of the homeostatic “gray” policy of Georgian Dream, which had taken over from Saakashvili in 2012. Unlike Saakashvili, who was a constant nuisance with his confrontations with Russia, Ivanishvili tried to avoid such confrontations at all costs and downplay the issue of occupied territory. Then when the life of the poisoned Saakashvili was literally ebbing in front of Georgian citizens, a considerable number of them sneered that the former president was simulating his poisoning. Interestingly, the situation was similar in 1992. Back then, the first Georgian president, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, became an exile in the wake of the coup organized by the pro-Kremlin Shevardnadze. After refusing to leave Georgia for Chechnya, Gamsakhurdia was forced to move from one Megrelian village to another without shelter or food, fleeing Shevardnadze’s squadrons, which planned to arrest him. Gamsakhurdia was found dead on December 31, 1993 in the village of Dzveli Khibula and declared to have committed suicide. It was not until 2011 that his death was confirmed to be an assassination. Before that, in 2007, he was reburied at the Mtazminda pantheon, where famous cultural figures and national symbols are buried. Similar to the present sneers towards Saakashvili, back then, well-known members of the cultural elite celebrated Gamsakhurdia’s defeat. Like Shevardnadze and his supporters who managed to make Gamsakhurdia a pharmakon, Georgian Dream and Ivanishvili have managed to make a pharmakon out of Saakashvili. As a result, not only does President Zourabichvili refuse to release or pardon Saakashvili, but a large swath of Georgian society feels no sympathy at the sight of his deplorable condition, which might prove fatal.

The New Poetics of the March 7–9 Protests

With the foregoing in mind, it is easier to answer the question of how the present protests are different from the previous ones. Why precisely did the proposed Law on Transparency of Foreign Influence provoke such rage, when other burning issues—like the corrupt courts and election system, political prisoners, and an economy rife with nepotism—did not?

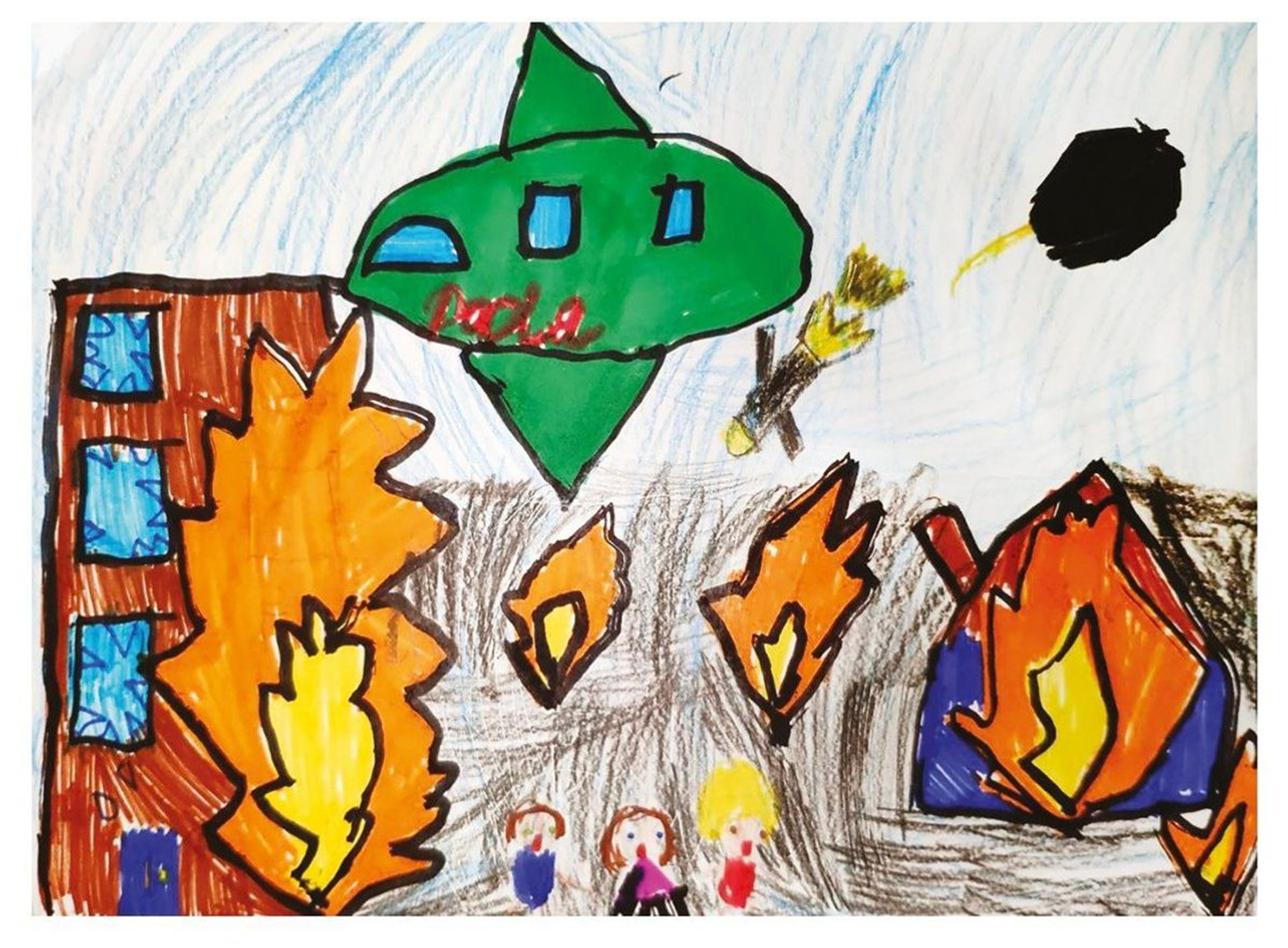

It was plain to see that this time it was not the opposition parties or their leaders who were the main participants in the protest. Instead, it was students between the ages of seventeen and twenty-five, who were not so visible in former uprisings. These protesters were not directed by any party and did not sympathize with any of the established powers. They managed to organize themselves without any external management. The so-called zoomer generation coordinated mutual care through horizontal arrangements—something that was not done so efficiently at party-based rallies in the past. Medical students provided treatment for the protesters, couriers brought food and water, and the youth quickly improvised defenses against tear gas and water cannons.

What was at stake this time was not only a concrete political issue, but the existential condition of each Georgian citizen—their education and healthcare, their well-being, their future, their career opportunities, all of which are of particular concern to younger generations. In Georgia, many NGOs, noncommercial organizations, media outlets, trade unions, cultural initiatives, hospices, and eco-movements are funded almost completely by Western money. Western funds support numerous institutions and initiatives that the state does not. Not only would this law “put its hand” into the pocket of each citizen; it would also control their travel, health, education, cultural production, creative practice, consumption, and leisure—life in general. Consequently, the law would jeopardize most noncommercial and nonpolitical civil initiatives that engage young people, to say nothing of the many Georgians doing low-wage work abroad to support their families.

What was completely new during the recent rallies was that the state security services, which previously were well informed about the organizational structure of domestic revolts, were caught off guard, precisely because the protests were decentralized and spontaneous. It also became evident that the carceral system was not able to detain an endless number of people. The spontaneity and energy of the protests were exhausting for the riot police and the state repressive apparatus. As some participants said in interviews, they are the generation that can dance through the night and go to lectures the next morning. Indeed, the audacity, sarcasm, humor, grace, playfulness, poetry, and even joy with which the youth confronted the repression hadn’t been seen before. The girls handing roses to the riot police or putting heart stickers on their shields; the teens, as they were sprayed by water cannons, holding up posters that said “Let’s splash”; the protesters humorously declaring, “If we wanted sirens and smoke, we would go to a dance club”—all these acts of defiance formed a collective political subject, which, despite the unequal struggle with the police, continued to resist courageously.

What is crucial in the formation of a political subject is the crossing of an invisible threshold. When this threshold is crossed, insurgents shift from fearing possible failure to courageously ignoring it and developing a condescending pity towards those whom they deem to be on the wrong side of history. At this juncture, the forces of authority no longer seem so powerful. The resistance comes to dominate the space of confrontation, making the punitive machine look exhausted and obsolete. The latter, it has to be admitted, was not as cruel in Georgia as it has been in Russia and Belorussia. Indeed, many wondered why the proposed law was withdrawn so quickly. Was it due solely to the protests, or were other circumstances at play, such as calls from the US and EU to Prime Minister Garibashvili and President Zourabichvili; Ivanishvili’s worries about the sanctions awaiting him and the fate of his frozen $600 million in a Swiss bank; or the fear that the Kremlin might cut off military aid if the protests did not end?

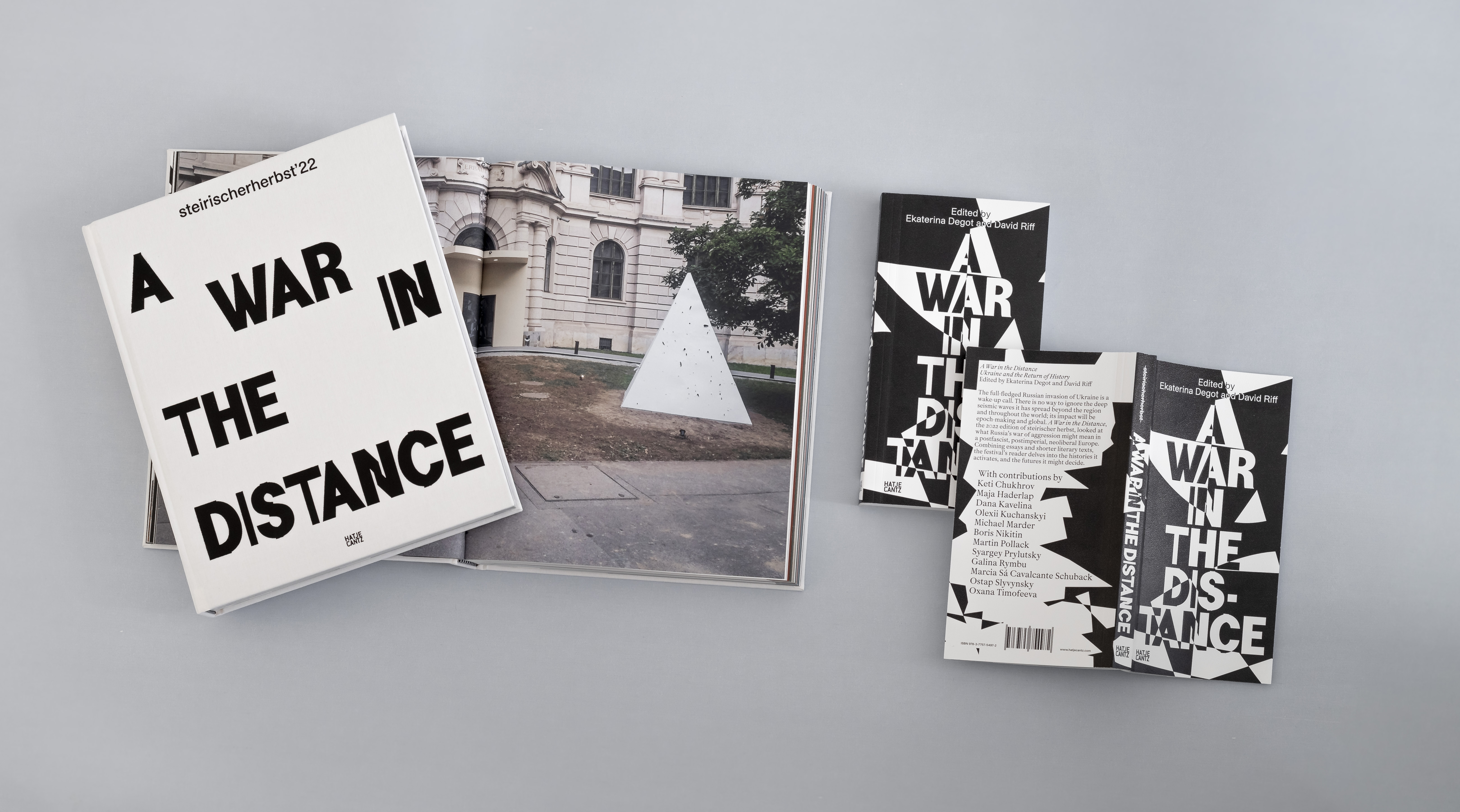

A more plausible explanation for the government’s abrupt change of course was the hitherto unseen unification of Georgian society around the EU and NATO path. Eighty percent of the Georgian population supports it. Georgians showed with these protests that those twelve stars on the blue banner are not simply a formal symbol. They have an existential value. Ukraine and Georgia make it evident that the ideas of the EU and NATO, even though they need critical reconsideration, are more relevant now than ever before.

A relevant question here is whether Putin backpedaled on his aspiration to join NATO in 2000 after he realized that a whole series of strict reforms would have to be imposed on the country’s ruling elite and social system.

Radio Tavisupleba, February 23, 2023 → (in Georgian).

Zaal Andronikashvili and Giorgi Maisuradze, “Gruzia – 1990: Filologema Nezavisimosti ili Neizvlechonniy Opit” (Georgia – 1990: The Philology of Independence, or the Unlearned Lesson,” NLO, no. 76 (2007) → (in Russian).

See Zviad Gamzakhurdia’s open letter to Eduard Shevardnadze, April 19, 1992 →.