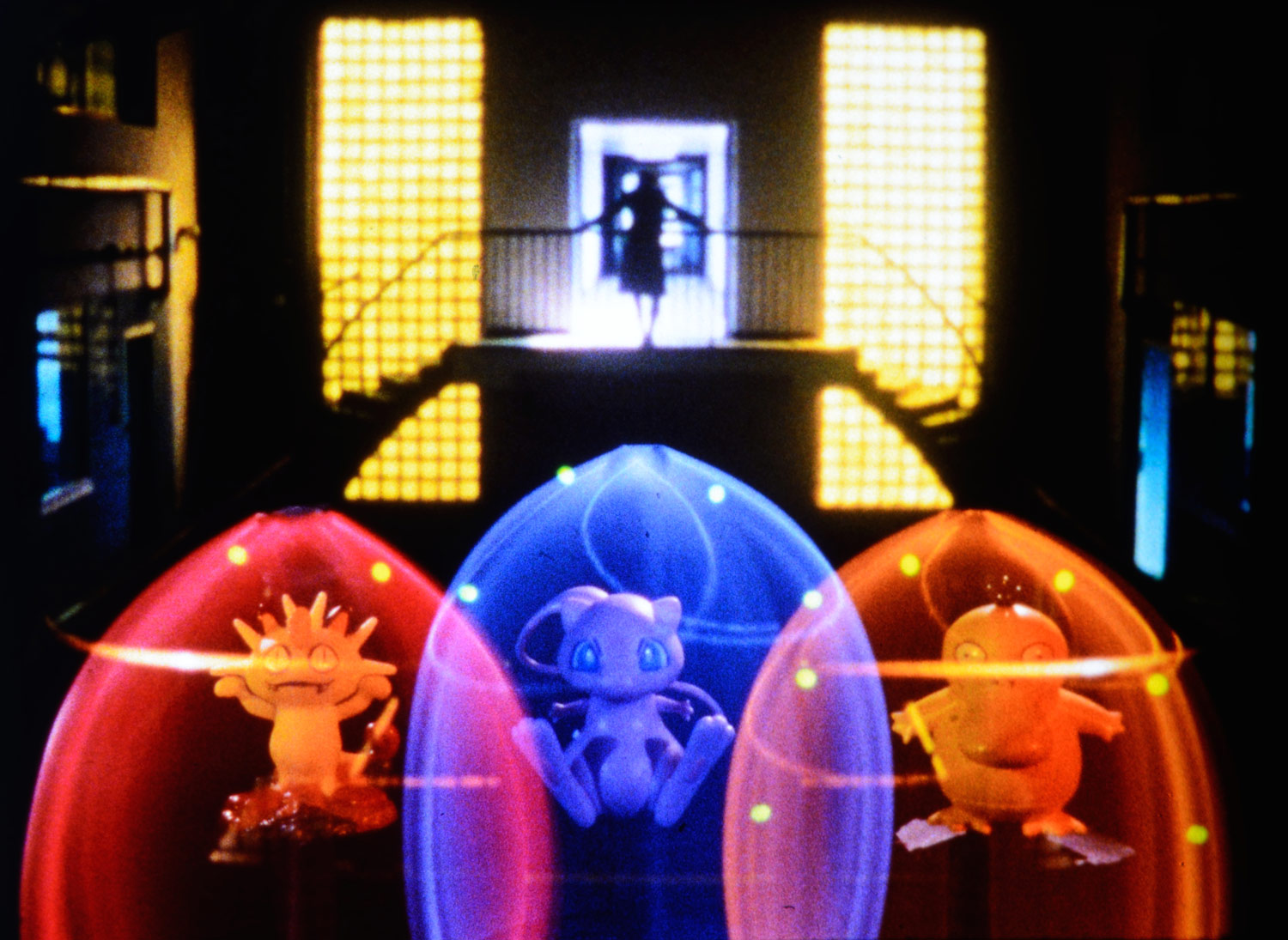

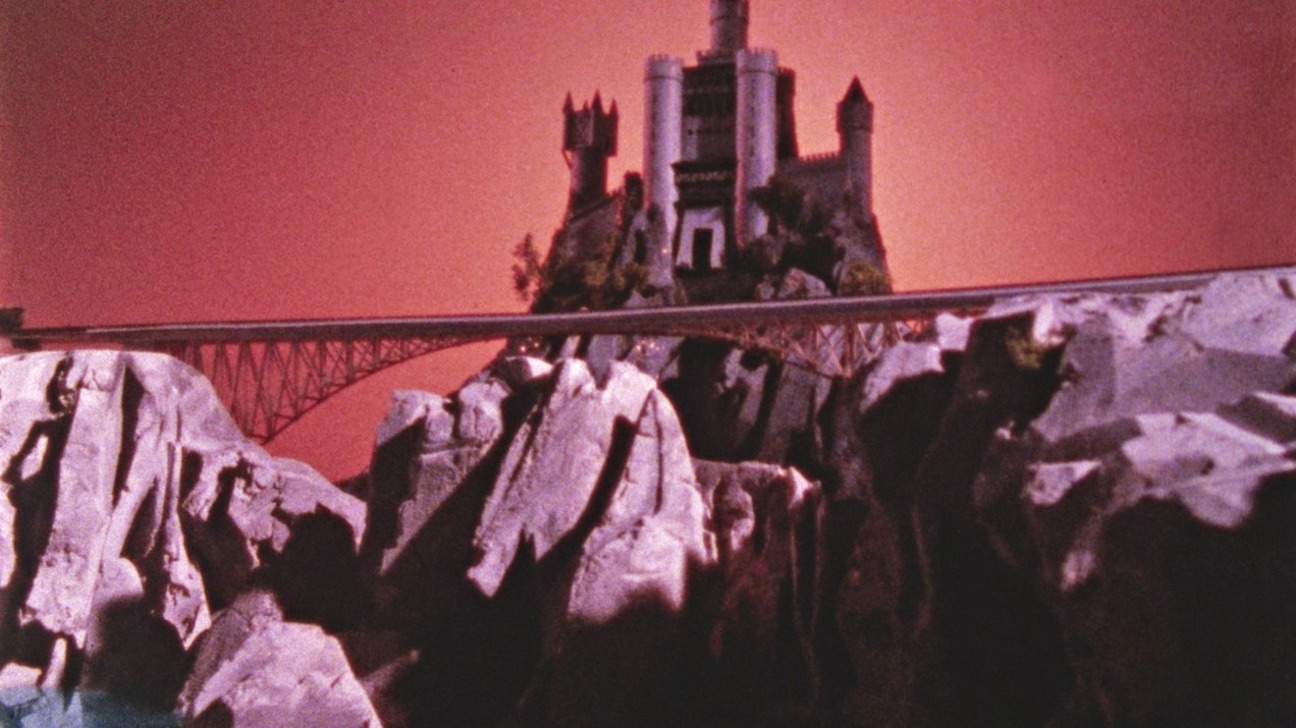

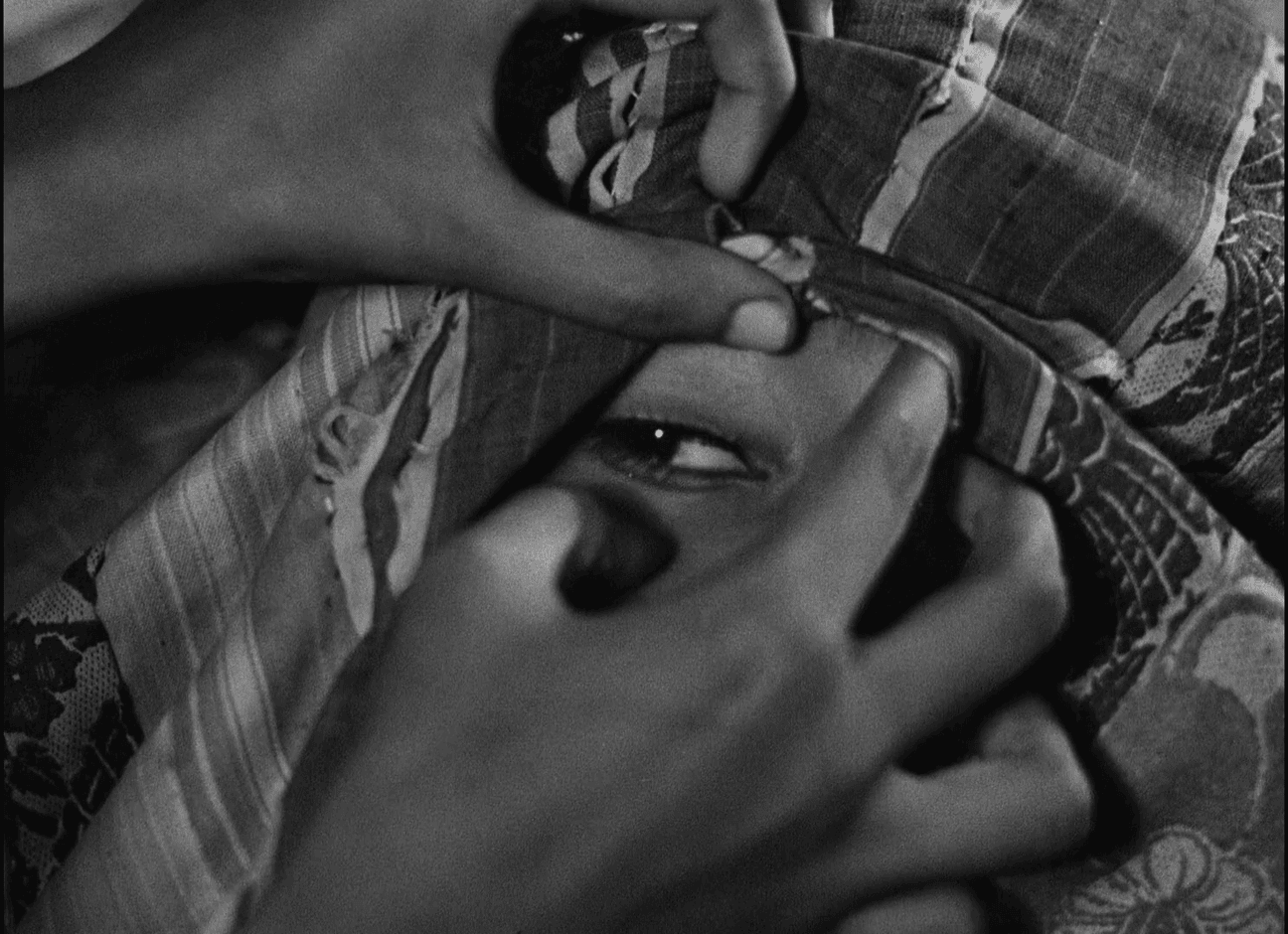

Film still from Jia Zhangke, Caught by the Tides (2024).

Read Pt. 1 here

The average adult blinks fifteen to twenty times per minute, which means about fifteen to twenty thousand times per day. If we did not blink at this rate, our eyes would dry out and in the long run we would risk becoming blind. In order to see, we need to not only open our eyes, but also close them. To be able to look, we need darkness as well as light: we need the absence of images as well as their presence. Today—as Leos Carax tells us in his beautiful video-essay It’s Not Me, presented at Cannes Première—the flow of images is so massive that even this minimal act of distancing has become impossible: we are more and more exposed to images, but are increasingly incapable of looking at and processing them. A quote from Paolo Cherchi Usai’s The Death of Cinema comes to mind: “A civilization that is prey to the nightmare of its [absolute] visual memory [author’s note: of a complete recording of every event, as happens with cell phone pictures and videos] has no further need of cinema. For cinema is the art of destroying moving images.”1 Cinema is not only the art of the persistence of phantasms of the past in the present, of their afterlife. It is also a practice of the destruction of images (every time they pass through a projector, they take one more step toward their death). It is a practice of becoming aware of the ephemeral and transient nature of images, which, subjected to the mechanical temporality of projection, tend to gradually disappear, and, after a certain amount of time, are also forgotten by the viewer. No technological apparatus can promise eternity. (It is yet to be proven that the zeros and ones of the digital universe will guarantee a longer life than the flammable nitrate of silent cinema.) Cinema consists of the decision to preserve some images and not others, to slow down the path to death for some while speeding it up for others. It is a decision about what to see and where to place our eyes. This is why, structurally, cinema has to do with desire: it is the act by which one selectively decides that I want to look here, and not there. It is ultimately an erotica: an act of selection within the visual of what we think re-gards us.

The visual universe of the digital has shaped a world where this decision is less and less binding. Different screens coexist with each other: one plays video games on a computer while at the same time watching a YouTube video on an iPad; one watches a movie, but from time to time checks social media on one’s cell phone. This also means that different worlds, different canons, and different communities can exist separately from each other. Decisions are less and less exclusive and differences are allowed to coexist. Cinema, with its modern practice of a desiring “selection”—“One screen is enough!,” as the public announcement used to go before Directors’ Fortnight screenings—is out of this world. It is a practice of choosing one screen at the expense of others. Cinema divides: it temporarily throws other screens into darkness to focus on only one. The digital visual, on the other hand, tends to dazzle us with too many screens, too many images, too many objects, too much light. Our eyes are blinded and can no longer “blink,” as Leos Carax says. And no longer being able to choose, we risk not being able to see anything at all.

In the context of this problem—an epoch-defining question concerning the anthropology of our vision, which no one who makes films today (filmmakers, critics, programmers, industry workers, etc.) can avoid addressing—David Cronenberg’s The Shrouds has something of a testamentary quality. It is a film that takes seriously the absolute visibility of the digital and brings it to its extreme consequences. Death, one of the last blind spots of our culture, is brought to full visibility. The resonance with Paolo Cherchi Usai should not be missed: if cinema is the art of the death of images, a post-cinematic world is not only timeless, but also deathless. Karsh, the film’s protagonist (played by Vincent Cassel), is a widowed entrepreneur who develops an app to observe in real time the decomposition of corpses inside their coffins. But even more than in the narrative, it’s in the film’s images that the absolute visibility of the digital appears: hyper-illuminated, flat, and deprived of any shadow, chiaroscuro, or texture. Everything is before us and everything is visible. And when images are so blindingly transparent, the only way out of this claustrophobic world is paranoia, i.e., the fantasy that someone is pulling the strings of our world even though we do not see them. Paranoia is the last frontier of resistance in a world that has become so prosaic that any possible transgression or conflict has disappeared. And even the proverbial emphasis on the flesh of bodies that is so typical of Cronenberg’s aesthetic appears in this film only in the form of dreams. In reality, everything is so anonymously abstract as to be turned into speech. The Shrouds is in fact also an incredibly verbose film, where speech spins around in circles in an endless and pointless discourse.

The post-cinematic nature of contemporary visibility appeared in the most interesting films at Cannes this year—including the ones that implicitly addressed the crisis of the cinematographic apparatus through a self-referential form. The result was a cinema that talked more and more about cinema and adopted the point of view of a spectator of itself, sometimes with fascinating results. Leos Carax’s It’s Not Me moves in this direction with a Godardian video-essay in the style of the Histoire(s) du cinema, made by recontextualizing film fragments (both Carax’s own and ones taken from film history) and by composing and decomposing bits of speech and impromptu reflections. A similar gesture, albeit in a less theoretical and more personal style (some have said: less Godardian and more Truffautian), was made by Arnaud Desplechin in Filmlovers! In this tribute to cinephilia, the French filmmaker combines references to early cinema and film history, anecdotes of contemporary moviegoers, disorganized personal reflections on cinema (particularly insightful is the part on Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah), and fictional scenes shot specifically for the film—we see again the typical habit of Desplechin’s male characters to neurotically use cinema as an excuse to avoid the sexual encounter.

Also in this year’s competition were several works with a strong meta-cinematographic approach. One of the most interesting films (which was, alas, completely ignored by the jury, as has often happened in Cannes with this director) was Caught by the Tides by Chinese filmmaker Jia Zhangke. In the film Jia recontextualizes several clips from some of his past films (notably Unknown Pleasures from 2002, Still Life from 2006, A Touch of Sin from 2013, and Ash Is Purest White from 2018), combining them with outtakes shot over more than two decades, and scenes shot in China during the pandemic. The film roughly sketches a melodrama in which two lovers from a provincial town in Northern China (we are in Shanxi, the region where most of Jia’s films take place) are separated because the man decides to immigrate to the big city. The woman later goes after him, though unsuccessfully, and when they finally meet again after many years, during the pandemic, it is too late. But if the narrative is basic to the point of triviality, what makes Jia’s film so fascinating is the dialectic between the characters and their historical context—or, one could say, between the foreground and the background. In the foreground we see the quotidian drama of the two protagonists, while in the background we see the development of Chinese history over the last thirty years (as well as of the economy and the world of production). From this repurposing and re-mediation of images shot by Jia over the span of a few decades emerges the awareness that the pro-filmic material of his films already represents the mark left by Chinese modernization on the film: a material testimony of what the plot then translates on a symbolic level. In revisiting fragments of old images from the early and mid-2000s, Jia does not only reflect on how Chinese development transformed (and often devastated) its landscape. He also inverts the relationship between foreground and background, where the details that had previously remained in the background in his older films now take center stage, reversing the internal relationships of the frame. If in the past Jia’s films had a particular story at the center and a universal historical-political context in the background, now our subjective position and gaze have shifted. We are driven to look first and foremost at Chinese history, and especially as how—from China’s entrance into the WTO in the early 2000s, to the Three Gorges Dam project, the Beijing Olympics, and the contemporary world of surveillance, loneliness, and artificial intelligence—a certain idea of the future was betrayed. The generation that believed Chinese industrial development and wealth would bring emancipation has become lost. With Caught by the Tides, it’s as if Jia is telling us that the core of his previous films was not the narrative structure but the long shots in the background. It was only a matter of positioning ourselves in the right place and adopting the right point of view.

There is also a lot of meta-cinema in Christophe Honoré’s effortlessly clever Marcello Mio, a film full of French movie stars who play themselves. The main character is Chiara Mastroianni, who, at the beginning of the film, on the set of a movie directed by a frustrated Nicole Garcia, is asked to be less “Deneuve” (her mother is Catherine Deneuve) and more “Mastroianni” (her father is Marcello Mastroianni). She takes this remark a bit too literally and starts to reconstruct her own identity based on the iconic image of her father. From that moment on, she will be Marcello Mastroianni: she will dress like him, talk like him, act like him (and this of course is facilitated by her extraordinary physical resemblance to her father). Marcello Mio thus develops ostensibly as a farce, somewhere between Pirandello and Freud, where the main theme is the paradox of identity and the performative dimension of one’s self-representation. And yet as the film goes on, as Chiara Mastroianni’s absurd imitation of her father is taken more seriously, a hint of anxiety emerges. For Marcello Mio is not only the story of a joke that goes too far. It is also a sequence of reenactments of Mastroianni’s old films (Visconti’s White Nights, Fellini’s La Dolce Vita and Ginger and Fred, and countless others). This series of references, rather than serving as light divertissements, become more claustrophobic as the film goes on. There are not only winks to the spectator and playful references to the history of cinema, but also an Escher-like construction where reality and fiction switch places in a theater of the absurd that constantly risks passing into the register of nightmare.

Meta-cinematographic referentialism was also found in Coralie Fargeat’s The Substance, one of the most polarizing films at Cannes this year (it nevertheless won Best Screenplay). In the wake of Julia Ducournau’s Titane (winner of the Palme d’Or in 2021), The Substance uses feminist detournement to subvert the cinema of some of the great masters of the past (De Palma, Cronenberg, Carpenter, Peter Jackson, but also Brian Yuzna’s Society), reflecting on Hollywood’s stigmatization of the aging female body. More or less explicit meta-cinematographic reflections also appeared in Paul Schrader’s Oh Canada, Jacques Audiard’s Emilia Pérez, and Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis, just to stay with the films in competition.

Perhaps that is why the jury, chaired by Greta Gerwig, decided to give awards to classically narrative, albeit beautifully made, films like Sean Baker’s Anora (which we will be hearing about for a long time) and Mohammad Rasoulof’s The Seed of the Sacred Fig (in which the feminist protests in Iran of recent years play a major role, along with the director’s flight from the country after being sentenced to eight years in prison for his opposition to the regime). These awards are perhaps the sign of an attempt—conscious or unconscious—to find a way beyond the crisis of the cinematographic form, a crisis whose causes are so deeply historic and so rooted in the new regime of the digital image that it does not promise to end anytime soon. This interregnum of profound uncertainty will no doubt continue to haunt future editions of the festival, as well as other places where the historical form of the contemporary image is discussed and reflected upon.

Usai, The Death of Cinema: History, Cultural Memory and the Digital Dark Age (British Film Institute, 2001), 7.