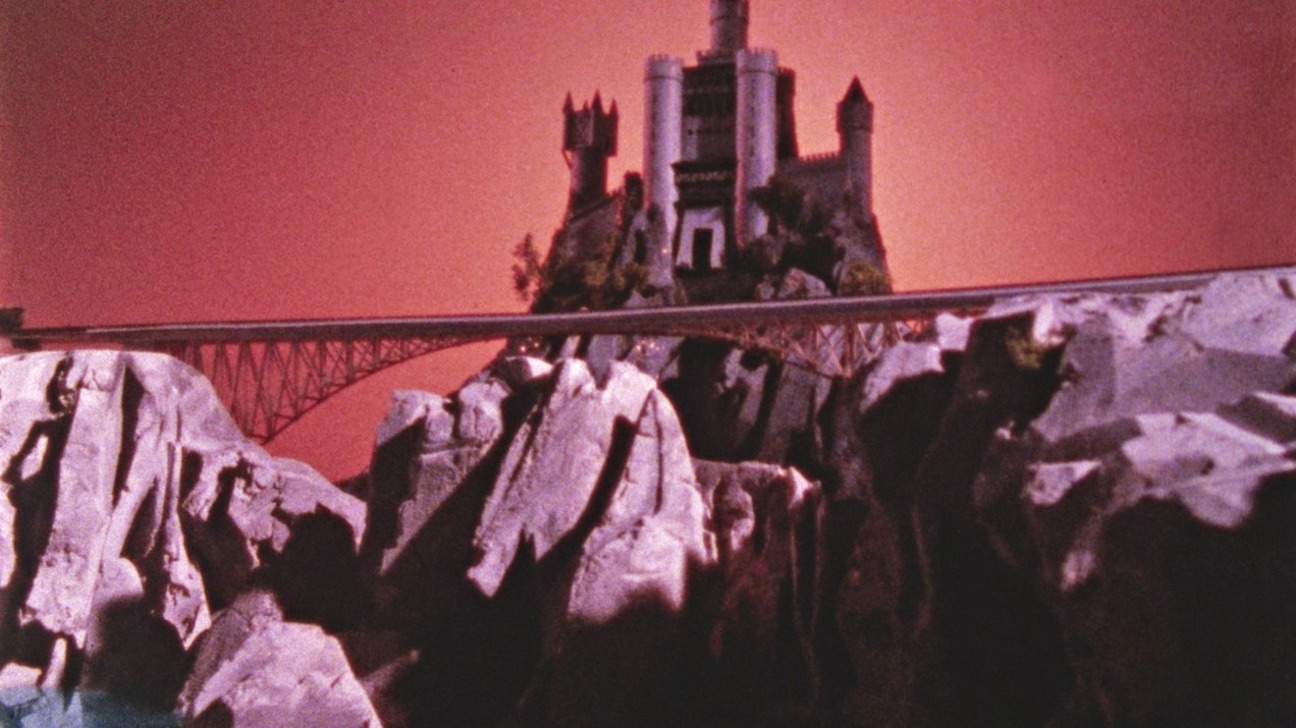

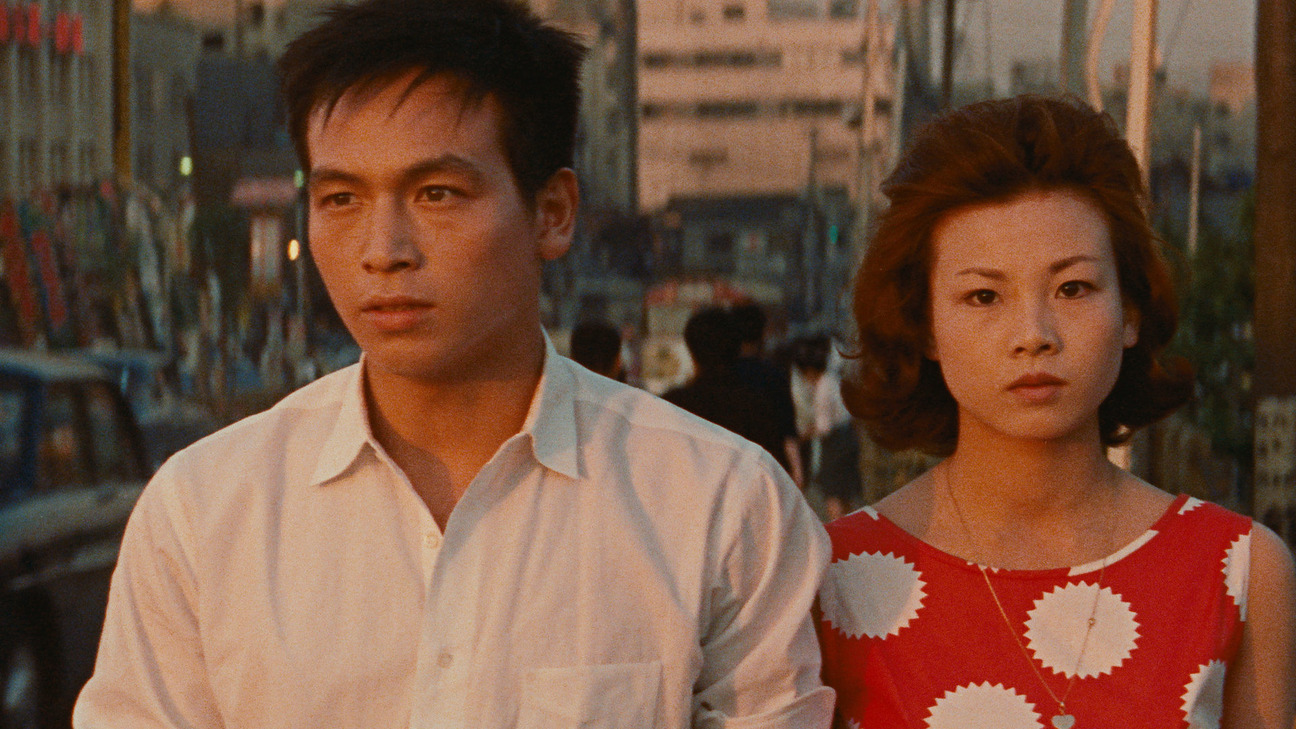

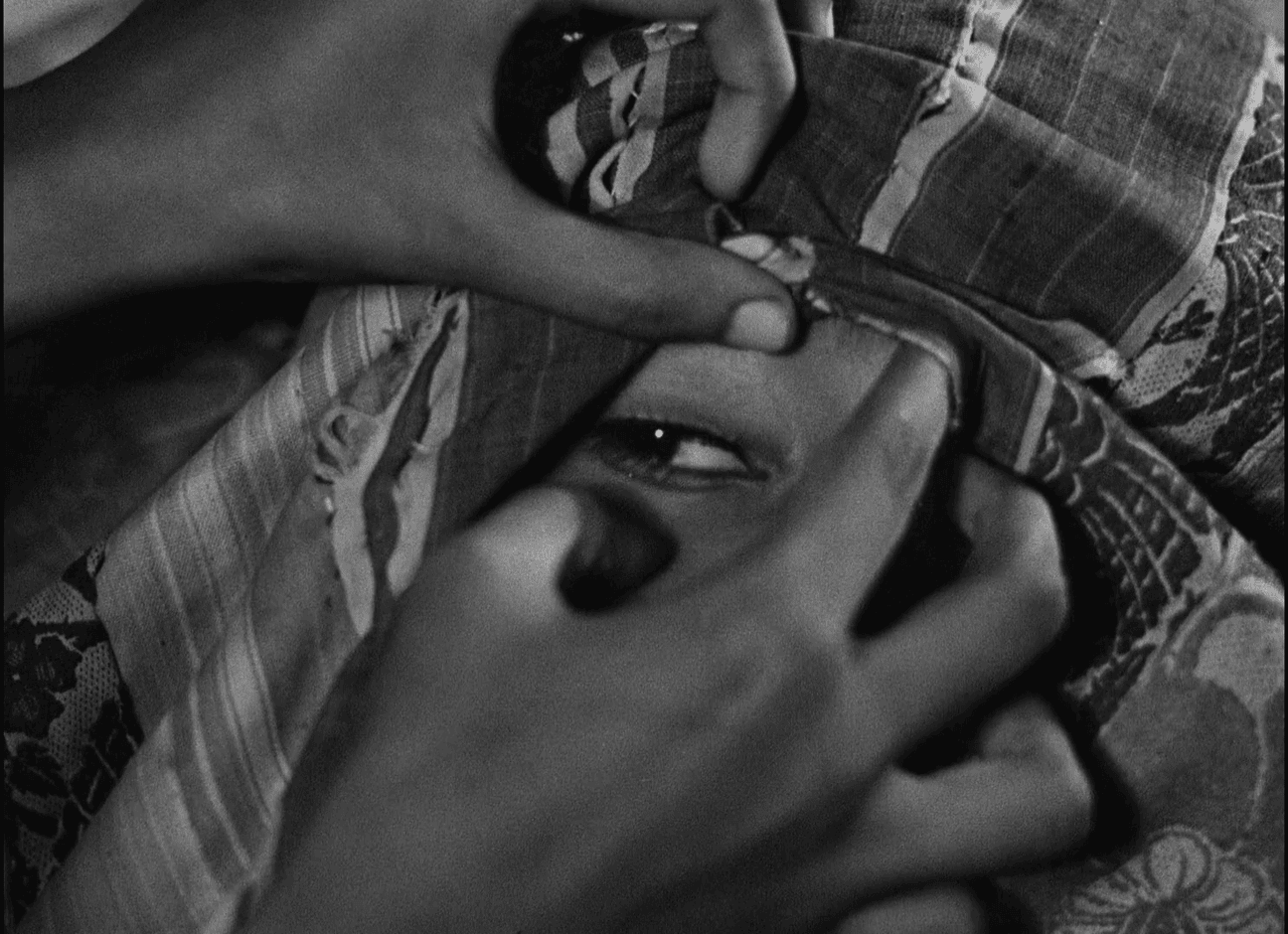

Still from Basim Magdy, 13 Essential Rules for Understanding the World (2011)

Last year we presented several works by Basim Magdy at the e-flux Screening Room. The screening was followed by a conversation between the artist, Lukas Brasiskis, and the audience. The transcript of this conversation was edited for the present publication.

Question: I would like to start by discussing your transition to filmmaking. How did you come to filmmaking from painting, and how do you perceive the importance of the film medium compared to painting? 1

BM: I studied painting, and at some point, I realized I needed the paintings to move. When I came across a Super 8 camera, I knew I had to make films. I watched a lot of YouTube tutorials on how to use it because I was too lazy to read the manual. Eventually, I made my first film, Turtles all the Way Down, in 2009. I couldn’t articulate my desire to present the idea as a film but there was something about working with the passing of time as a medium that felt immensely enjoyable.

Along the way, I realized I needed to figure out how to edit the film myself, so I watched more YouTube tutorials to learn how to edit. The same happened with sound editing. This was also cheaper than working with professional editors. But more importantly, I enjoyed doing all these things myself because the film’s direction would change as I worked on editing its components. I had an idea of what I wanted, but accidents happened, and bits of footage and sound started to fall into place beautifully and unexpectedly. If someone else were doing this, it wouldn’t have happened the same way. It would have become a different film.

It took me several films to get to the point where I understood why I wanted to make films in the first place. Making films allows me to talk about things with a different complexity from what painting and photography allow. Film is a sequence of fleeting moments that create meaning through sound, image, narrative, and time. The complexity of the layers within these elements and the variable relationships between them is where the magic is. Photography captures and freezes a moment, allowing for longer periods of contemplation, while painting lets you create a world from scratch. They complement each other, but filmmaking offers me a lot more because it evolves as I work on it. For example, when making New Acid (2019), I couldn’t write a script, so I built it day by day as I generated the text messages and pasted them onto the footage of the characters. The film developed very organically.

Q: You work primarily with analog film. How does this influence your vision, especially regarding the film’s ability to imprint time? Some, like Rosalind Krauss, argue that using analog film in contemporary art produces nostalgia. However, this doesn’t seem to be the case in your works…

BM: Each of my films is surrounded by personal circumstances and memories, but one thing I am aware of is that I try to confuse the sense of time in my films. I do not fully understand how time functions, but I know it passes and I am getting older. I often decide not to show the films in chronological order because I do not want to see the chronology of my life, or to limit the understanding of my films as such. Instead, I like to think of time as bringing the past, present, and future into a locked room to see what happens as they engage in a game of musical chairs.

Film, for me, is not about nostalgia. I did not grow up with film cameras. I came across my first camera fifteen years ago. When I discovered film, I became fascinated by its tangibility and what I could do with my hands—dipping it in acid to change colors, punching holes in it, leaving fingerprints. Its materiality and the fact that it almost died out with the abrupt advent of video, and then digital, made me feel that there was unexplored potential. This tangibility and materiality are crucial to my work, reflecting how humanity evolves in unexpected ways.

Q: Your work often presents a satirical and melancholic view of the possibility of utopia, acknowledging its unattainability while still exploring its remnants or flickers amidst the broader disillusionment and critique of modernist and Western-centric ideas of progress. How do you navigate this balance between critique and fleeting hope in your films, and what message do you hope to convey to the audience?

BM: If I could answer in one word, it would be the most underrated layer of reality: absurdity. There is an unmistaken sense of both failure and hopefulness—delusions of make-believe utopias and missed opportunities of capturing a truly hopeful moment—in most of my films. I make films about absurdity being a critical element of understanding and accepting reality. Things almost never go as planned, but they go somewhere, and we work with the new direction they take. This constant struggle to make sense of human lives and dreams is what creates hope. As long as there is a struggle, people find ways to create progress, both individual and universal. I think there is a lot of optimism in my films. You only get to see it if you allow yourself to accept absurdity as an integral part of reality.

I see everything I do as an expanded version of my medium—expanded cinema, expanded photography. I’m also currently working on creating what I see as expanded painting. This unquenchable desire to experiment with a medium beyond what it was intended to do is a reflection of my attempt to rearrange reality and make sense of it in new ways. Ultimately, I hope that people feel something when they experience my work, and hopefully this will lead to finding new ways of rationalizing what doesn’t make sense.

Q: Do you write scripts for your films? If so, can you describe the process writing them?

BM: It depends on the film. Most of the time, I start with an idea, write a little bit, and then begin filming. The filming usually happens in different places while I am traveling for exhibitions. I started filming that way, and eventually, I began going to specific places to film. But a lot of it is spontaneous—I find myself somewhere in front of something with a camera, and I just film it because I instinctively know I will use it in a film.

Basically, I keep going back and forth. I shoot a lot of footage in various places, get it processed, look at it, and start responding to it. Then I realize I need more footage, so I go back and film more. This back-and-forth process continues until I feel like I have enough material. I then start making the script more coherent and put it together. Often, things change during editing because some parts are too long or I lack footage for certain sections. The sound happens while I am editing. Before that, I am constantly recording things on my phone or sound recorder, but it all gets composed and constructed like a collaged tower of ideas during editing. I never really know exactly what will happen to the idea of a film until I start editing it.

Q: How do the limitations of Super 8 and 16 mm film, in terms of time constraints, affect your process?

BM: It is hell, I hate it. I wish I could film more. It is difficult, but it makes me think differently, and I like this process of thinking outside the box of abundance and availability. When I am filming, I am always counting in my mind, trying not to go beyond a certain number unless what I am seeing is really great and I know I need to keep filming. I am also constantly aware of the cost while filming. But after making a few films, you learn to trust yourself and know that regardless of how long or short the footage is, you will make it work in the editing.

Almost everything you see in my films is not staged. I find myself in places where people are doing really unusual things. For instance, in FEARDEATHLOVEDEATH (2022), there is a long scene with a man wearing a mask and holding a prop human head. I just happened upon this situation and felt compelled to film it until it felt right to stop. Knowing when to start and stop and which filter to use becomes intuitive. However, this intuition is grounded in experience—it comes from learning what works and what doesn't.

Q: Your films are quite wordy, yet you say you make films because you cannot express certain things in words. Why do you use subtitles instead of voiceover?

BM: The first part of your comment touches on something important. When I write for a film, I am writing specifically for that film. The script alone would not make sense to me. It only makes sense with the images, sound, and narrative. If I play my films without a soundtrack, they are boring and nonsensical. These elements have to work together. If I read the script out loud in conversation, you would think I was crazy. They need to exist together as layers of something more complex to create meaning.

As for the subtitles, it started with The Dent (2014). It is a film about an anonymous town with no identified characters, just people, a circus owner, a mayor, and an elephant. I wanted to keep everything anonymous. Using my voice or having someone read it would add certain connotations like gender and accent. I want to keep a door open for everyone to connect to it on some level, without creating a sense of foreignness or otherness. Relying on the English language still adds a layer that I would prefer not to impose, but at some point, you hit the limitation of not being able to use telepathy.

Q: What part of your work do you enjoy the most?

BM: It is always fun. I would not do it if it were not. I mean, it is pointless otherwise. I do a lot of other things in my daily life that are not fun. The filming, the editing—where the film becomes a film, putting all the pieces together—it is like entering a state of trance for days or even a month. There are always wow moments when you realize you can combine pieces of footage with sound or words that initially do not make sense but then start to. I enjoy all of it—painting, photography, writing poems—it is all fun.

Q: Your films often explore themes of death and limbo state between life and death. Does the question of life and death influence every project?

BM: It is in the background of everything I do because I am aware of it, and it is perhaps the one thing I cannot do anything about. In 13 Essential Rules for Understanding the World (2011), I played devil’s advocate, trying to be funny or sarcastic. But the sincerest rule was: “Think of death and the dead every day. Death will still take you by surprise, but you’ll be more prepared than others.” Eleven years later, I made FEARDEATHLOVEDEATH about the absurdity of death, embracing instead of understanding it and playing with this failure. The film is divided into chapters that do not make sense alone, but start to make sense when seen together in a sequence. The film is suspended in a state of limbo throughout its duration. It’s the limbo of seeing fragments of life that are about death.

Q: Can you talk about the influence of poetry on your work and its relationship with the handmade cinema techniques you use, like applying acid to film?

BM: When I was a teenager, I wrote really horrible poetry, like most teenagers. I stopped at 22 when I realized it was not good. Over 10 years later, when I started making films, I started writing the script for A Film About the Way Things Are (2010) and what I wrote came out poetic. I realized poetry does not have to be in poem form. It is about making sense of meanings and thoughts that can only be expressed in words. For me, filmmaking is about creating poetry through layering image, sound, and narrative together.

A few years ago, I started writing poems again. They are better now because I am older and hopefully more mature, and I learned to be less pretentious and to embrace failure better. I mostly just post them on Instagram and do not take myself too seriously.

Regarding film techniques, I started “pickling” rolls of film around 2013. Pickling is an existing process where you expose the film to different solutions to alter the colors of the image. I developed my own method where I expose my film rolls to household chemicals, mostly acidic solutions. When I pickle and shoot a film roll, I often know about 80 percent of the visual outcome. The rest is mostly pleasant surprises. I use this for my photography work and I’ve tried it with 16 mm film, where it creates what looks like an animated layer of dancing liquid on top of the subject I filmed. In FEARDEATHLOVEDEATH there is an animated sequence of punched holes and abstract marker drawings dancing to the soundtrack of a layered electronic musical composition—a sort of homage to Stan Brakhage. Both my daughters contributed ideas, sounds, editing, and an invented language to that film. Asking them to contribute somehow kept the film real.

Q: You are very open to your surroundings—even your children are allowed to contribute to your work—yet it seems to me that there is a certain sense of solitude in the way you make your films. How do you balance this solitary process of filmmaking with your emphatic engagement with the world?

BM: I am glad you see this. A lot of it is not intentional—it is an outcome of curiosity and a strong desire to do something about it. I am not trying to understand everything I am curious about; I am trying to rearrange things to find new ways of looking at what is familiar, to create an openness to different ways of understanding the enigmatic. I am happy this translates as empathy because empathy is extremely important. As I get older, I realize its importance more, especially after having children. Empathy and seeing the world from different perspectives are crucial. Let us say it starts with curiosity and ends with empathy.

You can watch the artist’s films on his personal website.