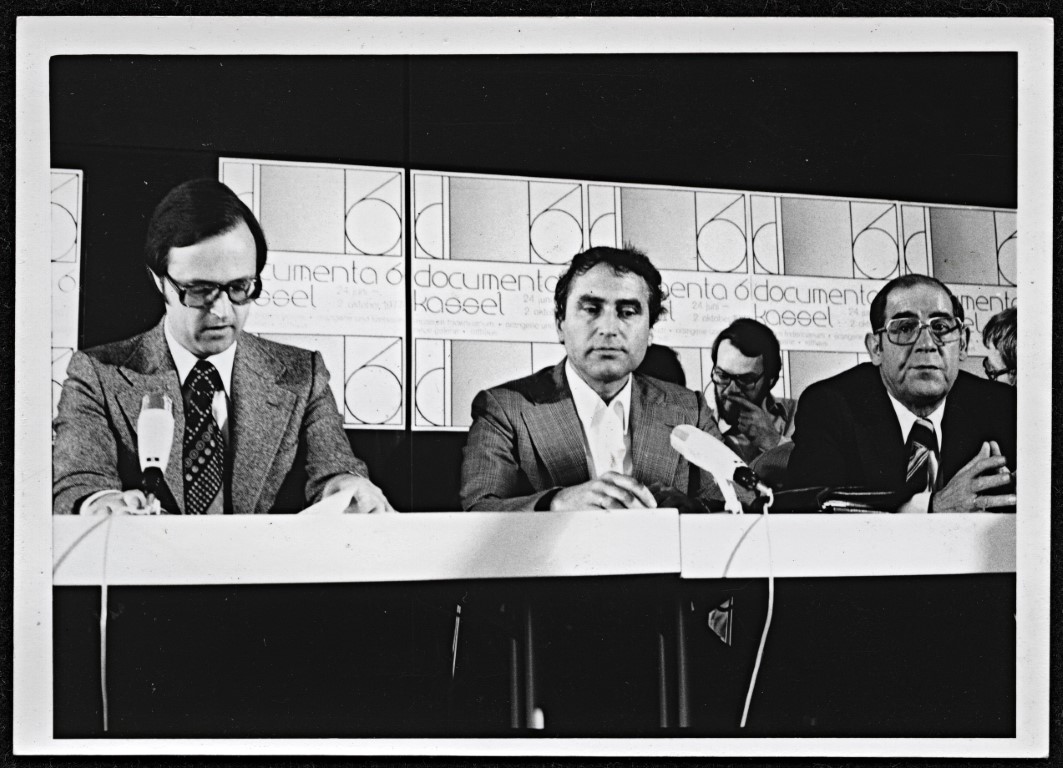

Bertolt Brecht, journal (detail), August 24, 1940. Courtesy the Bertolt Brecht Archive, Akademie der Künste, Berlin (BBA 0277/037).

Every intellectual in exile is mutilated, wrote Theodor W. Adorno in California during World War II. Adorno’s Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life, published in 1951, explores how life is fragmented by fascism, bourgeois society, and capitalism: “Private life asserts itself unduly, hectically, vampire-like, trying convulsively, because it really no longer exists, to prove it is alive.”1 In processes of fragmentation, truth vanishes. Capitalist ideology conceals this falseness with images that mimic life.

Another German in California exile, the playwright and poet Bertolt Brecht resisted mutilation with scissors and glue. Collage became Brecht’s operating theater in transit. His materialist dialectics, unfolding in a body of hundreds of fragments, sought to restore truth. Strikingly topical today, Brecht’s collages came to light only recently, with the largest exhibition of his visual work currently at Raven Row in London. Curated with the Brecht Archive in Berlin, the show gathers a vast selection of his newspaper clippings, multimedia storyboards, and photomontages, many of which have never been shown before.

One of Brecht’s albums (BBA 1198) contains large-scale collages documenting war, global financial crisis, and the rise of fascism. Dissecting Nazi propaganda, Brecht zooms in on the theatricality of collective gestures: The Wall Street Crash of 1929 is glued next to a crowd cheering Mussolini. Mourning mothers are pasted side by side with portraits of Nazi leaders. A snapshot of Bonnie and Clyde is juxtaposed with Hitler and Goebbels—they even wear the same hats! “Bonnie good girl gone wrong, mother says,” goes the heading for the bandits’ “bullet-riddled automobile.” Below, the Führer donates “for the suffering population in the Reich.” The collage suggests that capitalism and dictatorship are two sides of the same coin.

An absorbing montage in Brecht’s Bilderatlas fuses two photos: a small Hitler glued on top of a larger shot of a schoolboy. Both clinch their fists in a desperate attempt to show authority. It is a simple setup rich with symbolism. The photos persistently distort one another; their scale matters. Mimesis and doubling amplify the montage’s meaning: as above, so below. Who imitates whom? Is Hitler just a little boy asserting sovereignty? Brecht’s collage draws the gaze to a gesture oscillating between desire and drill. In miniature, Brecht captures the genesis of the fascist body immortalized by the soldiers in Klaus Theweleit’s Male Fantasies.

The images speak through their captions. Text is the architectonic framework of Brecht’s visual works—it transforms the page into a stage. Through the first caption, the viewer enters a German classroom in 1939: “His is the voice they hear over the radio. His the will they must obey.” A totalitarian eroticism of pure power. Young Karl Ernst, in the second caption, “repeats the lesson of the day,” towering over a Nazi newspaper. Every image is a mise en abyme, a myth of truth. Brecht loved clash and shock; he used to glue photos of sports cars and East Asian paintings onto his Luther bible. Collage operates at the sticky surface of images where new imaginative chains are released.

Encountering Chinese theater during a trip to Moscow in 1935, Brecht coined his famous concept of “Verfremdungseffekt.” In Mei Lanfang’s cross-gender performance, Brecht found a type of gesture that consciously reveals its own artificiality. Gleaned from the Russian formalists, Verfremdung is an operation of estrangement. Inspired by the Beijing opera, Brecht’s collages orchestrate and distort gestures. The truth of the image is its undisguised artifice—the mask never slips.

Epic theater, like a collage, is gestural and fragmented, fusing disjointed actions and imitations of action. Walter Benjamin wrote about his close friend’s theater that it “stretches” history through gesture. Epic theater does not develop action but mirrors reality by making it strange (Verfremdung). Brecht’s theatrical images and captions, on the other hand, aim at “exorcizing their sensationalism.”2 If theater was to show reality, Benjamin concludes, “then historical events would be, on the face of it, the most suitable.” History became the raw material of all of Brecht’s works.

On the day after the Reichstag fire in February 1933, Brecht left Nazi Germany, embarking on an odyssey through Prague, Paris, London, and Moscow to Svendborg, Denmark. Benjamin stayed with Brecht over the summer, chatting and playing chess. On July 24, 1934, Benjamin noted: “On a beam which supports the ceiling of Brecht’s study are painted the words: ‘Truth is concrete.’ On a window-sill stands a small wooden donkey which can nod its head. Brecht has hung a little sign round its neck on which he has written: ‘Even I must understand it.’”3 Similarly playful and bizarre, his collages aimed to restore concrete truth.

The exiled playwright became an obsessive collector, cutting out and collaging photos from newspapers. Brecht rearranged and glued the images, many of them war-themed, into a typewritten collage-diary known as Arbeitsjournal (1938–55). The London exhibition displays pages from Arbeitsjournal that montage text with drawings and found images—a permanent work-in-progress freezing the “waste products and blind spots that have escaped the dialectic.”4 An entry on William Wordsworth is illustrated by an image of soldiers in gas masks (BBA 0277/037). “One criterion for a work of art,” the text reads, “can be whether it can still enrich an individual’s experience.” On the opposite page he fixed a fragment on Greek epigrams paired with the cockpit of a bomber pilot.

Roland Barthes described Brecht’s work primarily as “a critique of the continuum.” Epic theater and collage are made up of discontinuous series of “cut-up fragments.” Deriving from the Latin “fragmentum,” “a piece broken off,” the fragment is a ruin that embodies and sublates rupture. In the German Romantic tradition, the fragment is at once isolated and interconnected. The Brechtian fragment is dialectical, for it “opposes reification (Verdinglichung)” and “refuses to affirm individual things in their isolation and separateness.”5 It is a paradoxical unity of opposite pairs, simultaneously moving and resting in a “dialectics at a standstill” (Benjamin).

Brecht’s anti-fascist photo-collages bring to mind Dada and surrealism. In the 1930s, Brecht was friends with the artists Georg Grosz and John Heartfield. They worked together for the socialist newspaper Arbeiter-Illustrierte Zeitung. In his famous stories of Mr. Keuner, Brecht wrote: “If newspapers are a means to disorder, then they are also a means to achieving order.”6 The operation of cutting, rearranging, and gluing newspaper clippings retrieves truth by deforming reality.

Passage from Bertolt Brecht, “On Restoring the Truth,” trans. Tom Kuhn, October, no. 160 (Spring 2017).

One of the first texts Brecht wrote after leaving Nazi Germany was “On Restoring the Truth” (1934), which emphasized the exploitative and dehumanizing nature of totalitarian language. In times of terror and deception, Brecht argued, it is the intellectual’s task to rectify falsehood. In the left-hand column he quotes Göring, to then “correct” his speech by juxtaposition. Brecht’s method of materialist critique operates through fragment and shock, not continuity and succession. His collages are a visual “seismology” of political gestures. Barthes suggested that Brecht’s critique operates as a process of surgical slicing:

“To unveil” is not so much to draw back the veil as to cut it to pieces; in the veil, one ordinarily comments upon only the image of that which conceals, but the other meaning of the image is also important: the smooth, the sustained, the successive; to attack the mendacious text is to separate the fabric, to tear apart the folds of the veil.7

As a trained doctor, Brecht felt immunized against ideology. Visual-textual fragments, one single torso being operated on, are the organs of his dialectics. Collaging is like sculpting with scissors: “Instructive for dialecticians, in fact something oddly good emerges at the end: the head is allowed to keep its contradictions unresolved,” as Brecht described the practice of the Swedish sculptor Ninnan Santesson, who hosted his family and other refugees.8 Collage is a sensuous form of critique that defers the resolution of contradictions.

Transiting through Moscow and Vladivostok, in 1941 Brecht boarded a ship for California: “Almost nowhere has my life ever been harder than here in this mausoleum of easy going.” In the same year, Adorno and Horkheimer arrived in Los Angeles, where they wrote Dialectic of Enlightenment. Attracted and repelled by their vicinity to Hollywood, the Frankfurt theorists reworked their theory of the image:

The senses are determined by the conceptual apparatus in advance of perception; the citizen sees the world as made a priori of the stuff from which he himself constructs it. Kant intuitively anticipated what Hollywood has consciously put into practice: images are pre-censored during production by the same standard of understanding which will later determine their reception by viewers.9

Film studios and the advertising machinery in the 1940s spit out their products factory-like: “The montage character of the culture industry,” Horkheimer and Adorno continued, “predisposes it to advertising: the individual moment, in being detachable, replaceable, estranged even technically from any coherence of meaning, lends itself to purposes outside the work.”10 Hollywood films impressed Brecht for their capacity to manipulate ways of seeing on a large scale—what Adorno and Horkheimer have called the mass deception of the “culture industry” which promises a flight from everyday existence.

Having worked in film before, Brecht tried his luck as a screenwriter in Hollywood. Though he wrote the script of Fritz Lang’s Hangmen Also Die! (1943), Brecht did not break into the industry. His collages, however, heavily borrowed from film editing and advertisement, often repurposing visual strategies. Word and image become paradoxical tools of revolutionary disruption. Montage techniques migrated into Brecht’s scriptwriting process. Under the shadow of Hollywood, he developed new ways of writing.

Rather than self-contained plays, Brecht produced a laboratory of performative miniatures. His storyboards are multidirectional, open, and mobile. Fragments of visually animated text can be endlessly recomposed and recycled. His unfinished play Fatzer, written between 1926 and 1930, tells the story of a tank crew who desert the army during the First World War (they write “we are done” on their tank). Fatzer’s refusal of war feels explosive and liberating today. The Fatzer fragments consist of poems, photographs, and diagrams, typed, drawn, and glued on scraps of paper. Brecht’s script is a multimedia work-in-progress.

Bertolt Brecht, from The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui manuscript, 1941. Courtesy the Bertolt Brecht Archive, Akademie der Künste, Berlin (BBA 0174/042).

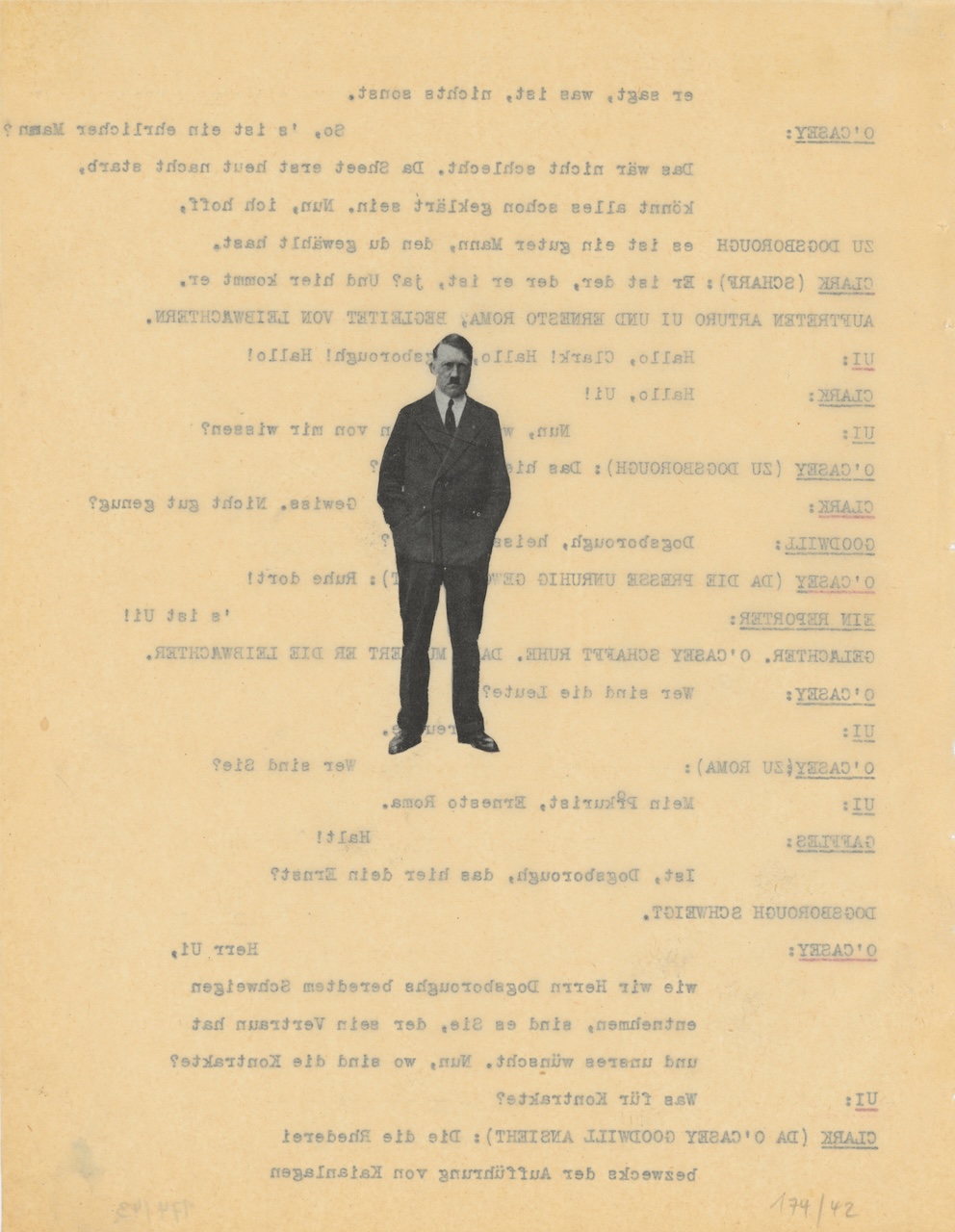

The script of his “parable play” The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui (1941), about a cauliflower racketeer in Chicago, is typed on transparent paper, heavily illustrated with cutout paper dolls, including Hitler in a suit. Working through the fragments of Arturo Ui, Brecht began to read Marx “and for the first time, my own scattered practical experiences and impressions really came to life.”11 Similar to Marx’s Capital, Brecht’s collages create a morphology of capitalist political economy, based on the logic of contradiction.

Brecht’s dialectical method came to full fruition in his famous War Primer (Kriegsfibel), first published in 1955. Raven Row exhibits some original “photo-epigrams” from the anti-war album, capturing the Blitz, exhausted soldiers, desperate refugees, and blinded children. Its shocking micro-poetry equals Goya’s Disasters of the War: “Those you see lying here, buried in mud / As if they lay already in their grave— / They’re merely sleeping, are not really dead / Yet, not asleep, would still not be awake.”

Brecht’s collages tell history not from the standpoint of the victor, the ruling class, but from that of the defeated, from below. They lend their voice to the forsaken, minor, oppressed. His collages spark revolutionary hope: “Don’t start from the good old things,” as he liked to say, “but the bad new ones.”12 And if only for one sticky moment, damaged life has proved that it is alive.

Theodor W. Adorno, Minima Moralia: Reflections on a Damaged Life (Verso, 2005), 33.

Walter Benjamin, “What is Epic Theatre? (Second Version),” in Understanding Brecht (Verso, 1998), 16.

Benjamin, “Conversations with Brecht,” in Understanding Brecht, 108.

Adorno, Minima Moralia, 151.

Adorno, Minima Moralia, 71.

Bertolt Brecht, Stories of Mr. Keuner (City Lights Books, 2007), 65.

Roland Barthes, The Rustle of Language (University of California Press, 1989), 216.

Bertolt Brecht, Journals 1934–1955 (Bloomsbury, 1993), 36.

Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments (Stanford University Press, 2002), 65.

Horkheimer and Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment, 132.

Brecht, Journals, 4.

Cited in Benjamin, “Conversations with Brecht,” 121.