Évariste Vital Luminais, The Sons of Clovis II, 1880. Collection: Art Gallery of New South Wales. License: Public domain.

This is a lightly edited excerpt from Benjamin Noys’s Envisioning the Good Life: The Limits of Contemporary Vitalism, published by Edinburgh University Press.

In response to the crisis of Covid-19, and the ways in which that crisis revealed various aspects of the endemic crises of the present, issues of care, healthcare, and the need to preserve life have become more urgent. These issues never went away and it has been a luxury for some that they have become a mere background. We not only have the crisis of Covid-19 but also the ongoing and inevitable crises caused by global warming and the aftereffects of the global capitalist crisis of 2008 to 2009. There are also signs of increasing inter-imperial rivalry and instability that makes past prognostications of a new peaceful global order look naive. How do we imagine the good life while living in bad times?

The question of the good life is central to philosophy. My aim here is not to explore the various ways this question has been posed throughout the history of philosophy. Instead, I focus on the twenty-first-century moment of the thinking of life and offer a critical analysis. This is not a clear demarcation of thought, as the thinkers I examine have their lineages, particularly in the nineteenth and twentieth century. My concern is with what I call contemporary vitalism, which I treat as a broad category of those who invoke a force of life that exceeds determination. These thinkers imagine life as a power or force that resists containment and discipline. It is a force that is rebellious and disruptive, and it is in this force that the good life can be found. This is an envisioning of the good life as a mythic escape from our fallen reality into a life lived in all its immediacy and power.

It is not surprising that such a notion of life should become prevalent and not surprising that it should be attractive. A life beyond the limits of our crisis-wracked present, which would transcend the forms of historical suffering, is a powerful vision. This image also recalls the Christian vision of life as saved and redeemed in a new kingdom that would spell the end of earthly powers and dominions. I do not want to suggest that this vision of a transfigured life that would realize freedom is simply to be cynically derided or dismissed as a religious illusion. Instead, my point is that these vitalist thinkers cannot deliver on this vision of the good life and that they also mirror and maintain some of the very features of the present that prevent the realization of the good life. I wish to analyze why this is and to suggest an alternative image of the good life that does not give in to despair. The vitalist vision of life overflowing all determinations, while optimistic and celebratory, can encourage a sense of despair by its failure to realize the good life it promises.

Vitalist thinking is so capacious that it can absorb the worst fates of life. Alongside the celebration of life as beyond determination there is also an allied concern with life as exposed and damaged. If life is to be transformed into the good life then life as suffering must also be redeemed. We can see this clearly in the work of Giorgio Agamben, who is best known for his analysis of life as abandoned to its subjection to power. This analysis of bare life, made in the 1990s, would be acutely prescient of the modes of power of the war on terror: new camps belonging to no obvious legal authority; privatized and mediatized forms of torture; and new modes of mass surveillance and discipline. Agamben was also concerned with a redemptive project of realizing a utopia beyond bare life. This would involve a new political good life operating beyond state and capitalist violence. While Agamben is often seen as a pessimistic thinker he also promises a realization of the good life that would redeem bare life. This kind of movement is key to this book. Vitalist thinking not only suggests the power of life, but it also traces that life in its fallen forms and tries to redeem it. These visions are powerful, but I want to dispute their capacity to truly grasp and deliver to us an actual experience of the good life.

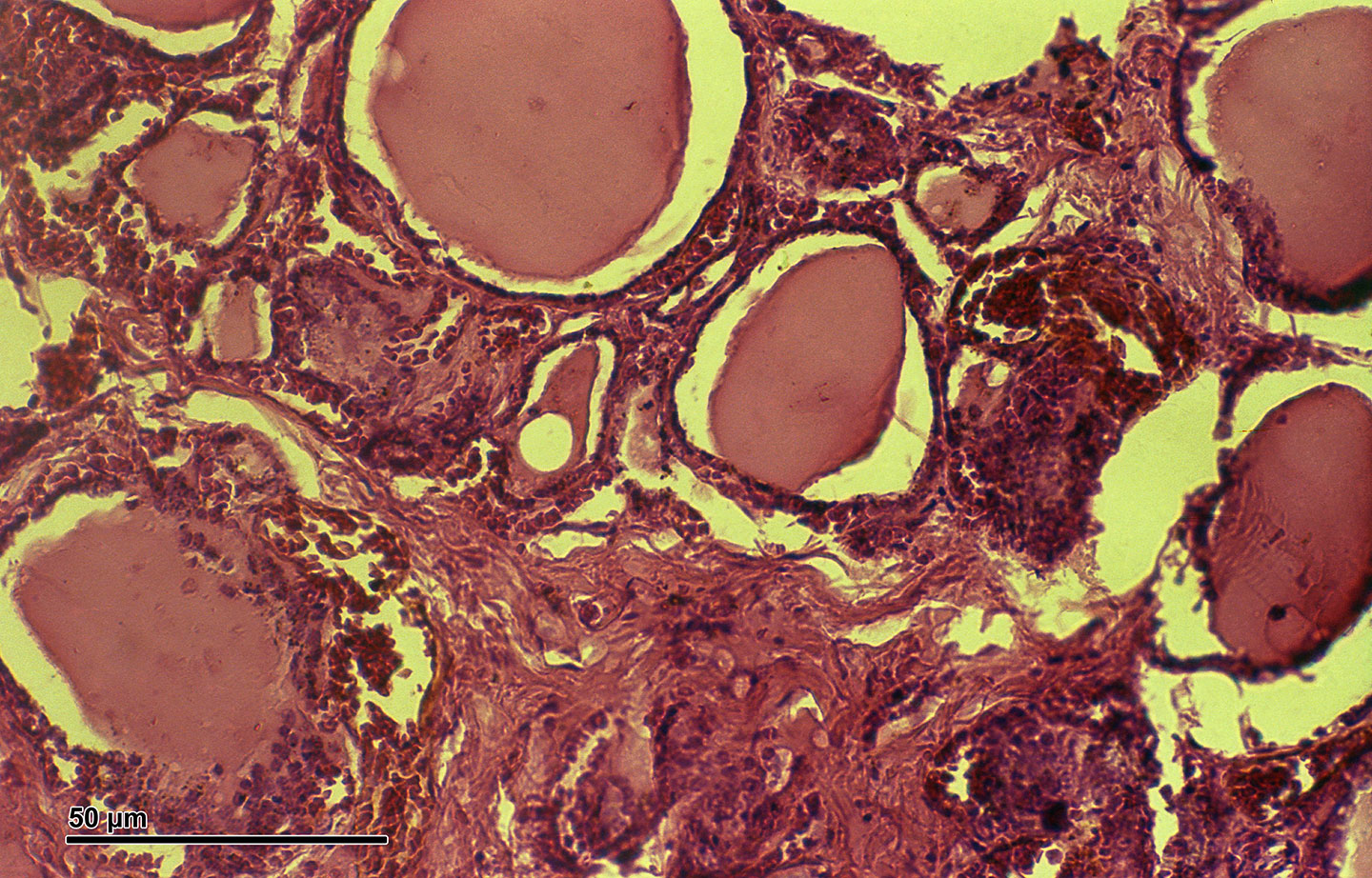

To return to the pandemic, Agamben has attracted controversy because of his resistance to measures of state control, especially lockdowns, as the means to deal with Covid-19. The biopolitical model that Agamben in part derives from Foucault has been antagonistic to methods of disease control that aimed to preserve life through various forms of restriction. This revealed troubling features of the biopolitical thinking of life beyond control. The pandemic lockdowns could be disputed as methods of dealing with the virus and they did have deleterious effects. Agamben’s thinking, by associating all such measures with control, neglected the dimensions of control that not only protected life but which also had popular support. The biopolitical opposition of life to control was not equal to a mass biopolitics which demanded the preservation of life, especially of some of the most vulnerable in our society, the elderly.

I want to explore life as part of the totality of nature and society rather than as excess. My aim is not to extract a concept of the good life as something excessive and indeterminate but rather to suggest that the good life lies in a collective experience integrated into the totality of social being and the totality of nature. In the context of Covid-19 such thinking can help us understand how this disease emerged and spread—from our impinging on nature and so creating new vectors for viruses to emerge, to our need for a collective and coordinated global response to deal with the disease. In practice, such an understanding was limited, and this is part of the problem. Our failure was to not understand and act on a vision of life as integrated, precisely due to the fragmentations imposed on life in the present. My aim is to find this vision of integrated life, rather than to elaborate a life separate from the fallen present or a new myth of redeemed life. This vision of the good life involves the work of joining in the connected experience of life. It lies in a mass biopolitics that does not simply oppose life to power, as vital force to oppression, but also demands that life be sustained and cared for beyond and before power. Thinking life in this integrated fashion is not simple or easy to achieve. To find this concept of life involves a patient working through of the limits of vitalist thinking and moving beyond these limits.

Vitalism has been concerned with providing not so much the truth of life but a galvanizing myth of life, linking life to the power of myth as a motivating force. The difficulty is not only with the vision of the good life as excess, but also that this vision becomes a myth that replaces reality and becomes an end in itself. This is why I do not aim to provide a new myth of the good life or to suggest the imagination of the good life as an end in itself. Today, we are often told we lack the capacity to imagine a better future and a better life. That might be true, to an extent, but I think it is more important that we start to imagine what dimensions of the good life we have now and how we can globalize them. It may be that we know already, often at an unspoken level, what the good life is. I hope to help in the articulation of the good life we already know.