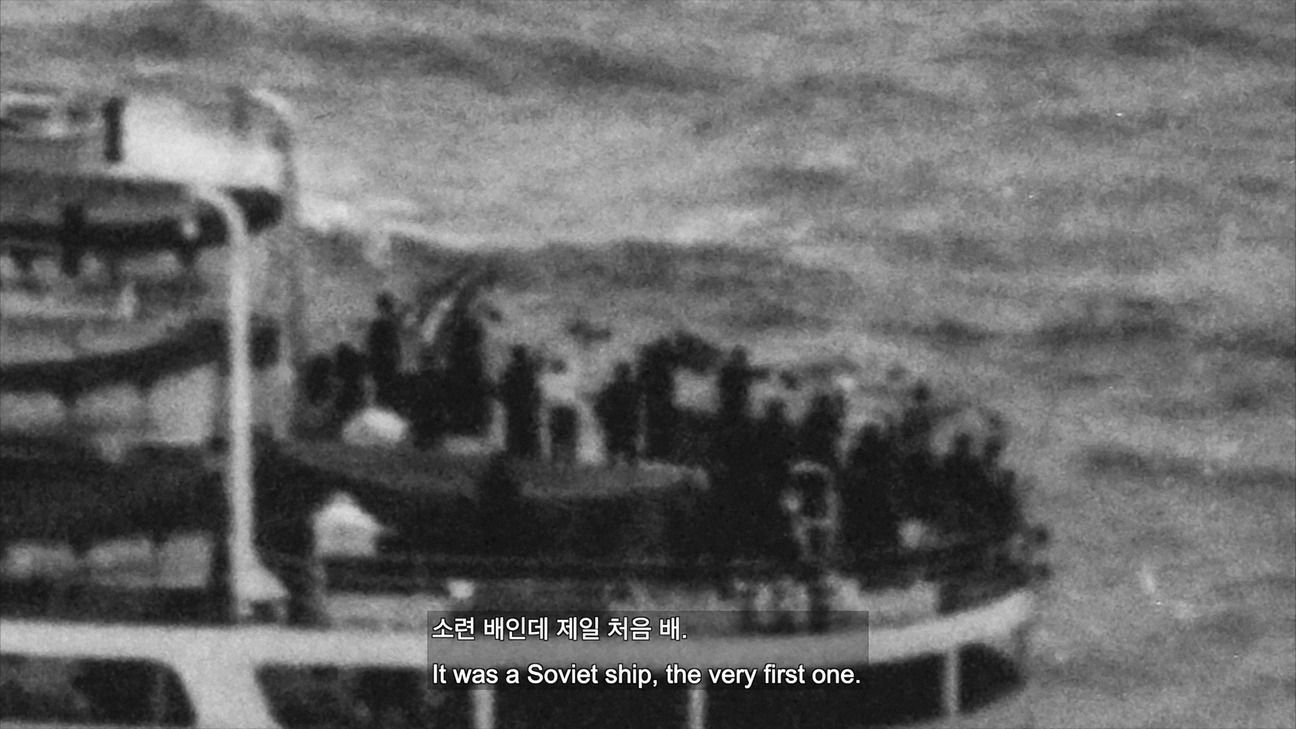

Nam Hwayeon, Coréen 109 (still from single-channel video), 2014. Courtesy the artist.

We are pleased to publish Adeena Mey’s contribution to Film Notes, in which he reflects on the moving image practice of the prominent Korean artist Nam Hwayeon through the notion of a "choreography of thought." The text considers how Nam’s works navigate the complexities of archival memory, embodied knowledge, and the shifting geographies of inter-Korean and inter-Asian histories.

Choreography Against Cartography

Nam Hwayeon characterizes her work as a “choreography of thought,” a term that refers to both her methodology and to the subjects she explores and that are figured in her work, through single channel moving image works, video installations, or archival displays.1 The choreographic, in Nam’s work, not only covers the term’s more restricted understanding as the transcription of dance and what makes it legible but also emerges as a kinetic and epistemological force that informs her methodology of “artistic research.”2 Many of the archives Nam investigates speak to the knotty narratives of Korean histories, fraught with claims to truths and positive knowledge. In this regard, through the choreographic, Nam reinscribes the body as the site of an expanded agency able to convey and articulate narratives that escape through the cracks of the officialdoms of the Japanese colonization of Korea, of Pan-Asian histories, of the division of the Korean peninsula, and of its place within transnational dynamics.

Functioning as a topic that traverses most of her work, the body—our actual corporeality as well as the multiple metaphors the term supports—populates her work under various guises. The bodies of the dancers, choreographers, singers and performers; the bodies of knowledge that she surveys, themselves often seen as being passed and transformed through the corporeal bodies that carry them; and the body politic and its claims to ownership, truth, and objectivity over information that Nam examines. These bodies each have their corresponding institutions—the theatre and the museum, the library and the archive, and the state. Official, sanctioned, conventional, or normative forms of knowledge production operate according to a logic of border that names, classifies, and categorizes. In this sense, such knowledge is cartographic. But Nam, like the histories and the people she has been examining and is in dialogue with, is a border crosser. If there exists an anamorphic relationship between normative ideals of the body, knowledge produced from the archive, and the state-form, then what about choreography? What type of body enables it and what body of knowledge does it produce? What kind of relationship is there between corpus and thought?

A corpus is a body—un corps, if we follow its etymology and French philosopher and musicologist Peter Szendy’s ruminations on the term. “For Szendy, a corpus carries an organic quality—a certain homogeneity—and organology, traditionally embodied in the rhetorical figure of effictio, is the discourse that describes a body from head to toe, rendering its shape intelligible through words. This exhaustivity is deceptive and is in fact the mark of the very limit of describing head to toe and the drive for complete capture that subtends it. Therefore, for Szendy, the very notion of a corpus should be rethought. In Phantom Limbs: On Musical Bodies (Fordham University Press, 2015), he does so by drawing on music history, closely examining Thelonious Sphere Monk playing the piano, Bach’s fingers multiplying as he performs, and the hybridization of musicians with their instruments, among other sonic phenomena. These moments reveal the limits of conventional organology and of perspectives based on a corpus that they repress or are unable to grasp, namely what “effictions” actually do, that is creating “bodies made of fictions”; for Szendy, it is what he calls a “general organology” that renders such effictions legible.3 In this regard, with her choreography of thought, Nam expands general organology, not only accounting for effictional organisms, but also for their movements towards the fictional, the virtual, and multiplicity.

Nam’s methodology also invites us to rethink our understanding of geo-bodies, of conventional maps and of cartographic and border thinking. Actual maps and diagrams do appear in her work. The single-channel video essay Coréen 109 (2015) is composed mostly of still images with a voice over narrating Nam’s research into the Bibliothèque nationale de France holdings. In Coréen 109, these stills include a hand drawn map of the library’s neighborhood and a colonial map of Africa. In Imjingawa (2017), Nam investigates the lives of the song Imjingawa—composed in the 1950s in North Korea to evoke the longing for reunification, and adapted in 1968 by the Japanese band The Folk Crusaders into a hit that was quickly banned due to political sensitivities. Among direct documentary-style footage shot in Japan, interviews, and archival images, she introduces a map of Shinjuku metro station, inserted as a metonymy for the locations evoked.

The three-channel video installation Throbbing Dance (2017) brings together a North Korean music video with scenes from a dance rehearsal. The latter makes uses of diagrams drawn on the floor of dance studio for a piece to be performed, serving as visual aid for the South Korean performers. Yet such visualizations remain on the level of the representational. The navigation across gaps between the latter and the new spatial configurations emerging from the whole of an edited work choreograph new geographies beyond actual geo-bodies. Subjects referencing inter-Korean, inter-Asian or transnational histories are recurrent in Nam’s oeuvre. They include Zainichi Koreans (long-term ethnic Korean residents of Japan, many of whom are descendants of Koreans who migrated or were brought there during Japan’s colonial rule over Korea between 1910 and 1945) and the life and legacy of famed twentieth-century Korean dancer and choreographer Choi Seung-hee’s project of an “inter-Asian dance.” In Against Waves (2019), Han references Choi’s life and the significance of her writings on the hybridization of traditional dance with Western dance aesthetics in scenes featuring Zainichi choreographer Kyunghee Lee—seen both performing and interviewed—interspersed with archival imagery. Against Waves and other works reflect Nam’s interest in geo-political formations largely shaped by the imperial project of Pan-Asianism and of the question of “Asia” itself.4

Nam Hwayeon, Against Waves (still from single-channel video), 2019. Courtesy the artist.

To bring the metaphor of the organism in this again in its capacity to make sense of space and geography this time with regards to Asia, one should be reminded of the association of a notion of organicity with grand civilizational and panregionalist imperialist projects. As Japanese scholar Naoki Sakai has noted, “what is at stake in this persistent endeavor to distinguish Europe or the West from Asia is the very identification of the West, for its identity is in fact anxiety-ridden.” He continues: “What must be kept in mind under the climate of fascist populism is that anthropological difference, the very distinction of European humanity and Asian humanity, is essentially and in final analysis a figure of ressentiment. However, as a matter of fact, the derivative character of the first statement in relation to the second is inherent in the designation of ‘Asia’ itself.”5 Centering subjects with multiple or no clear origins who interfere with the laws of land and identity and amplify cracks, polyphony and paradoxes, Nam’s choreographies reveal the phantom limbs of geo-bodies without borders.

Keepers of Knowledge?

In her work, Nam traverses the interstices between official knowledge and its institutional agents, and the spaces where such sanctioned knowledge is unsettled, resisted, or exceeded.

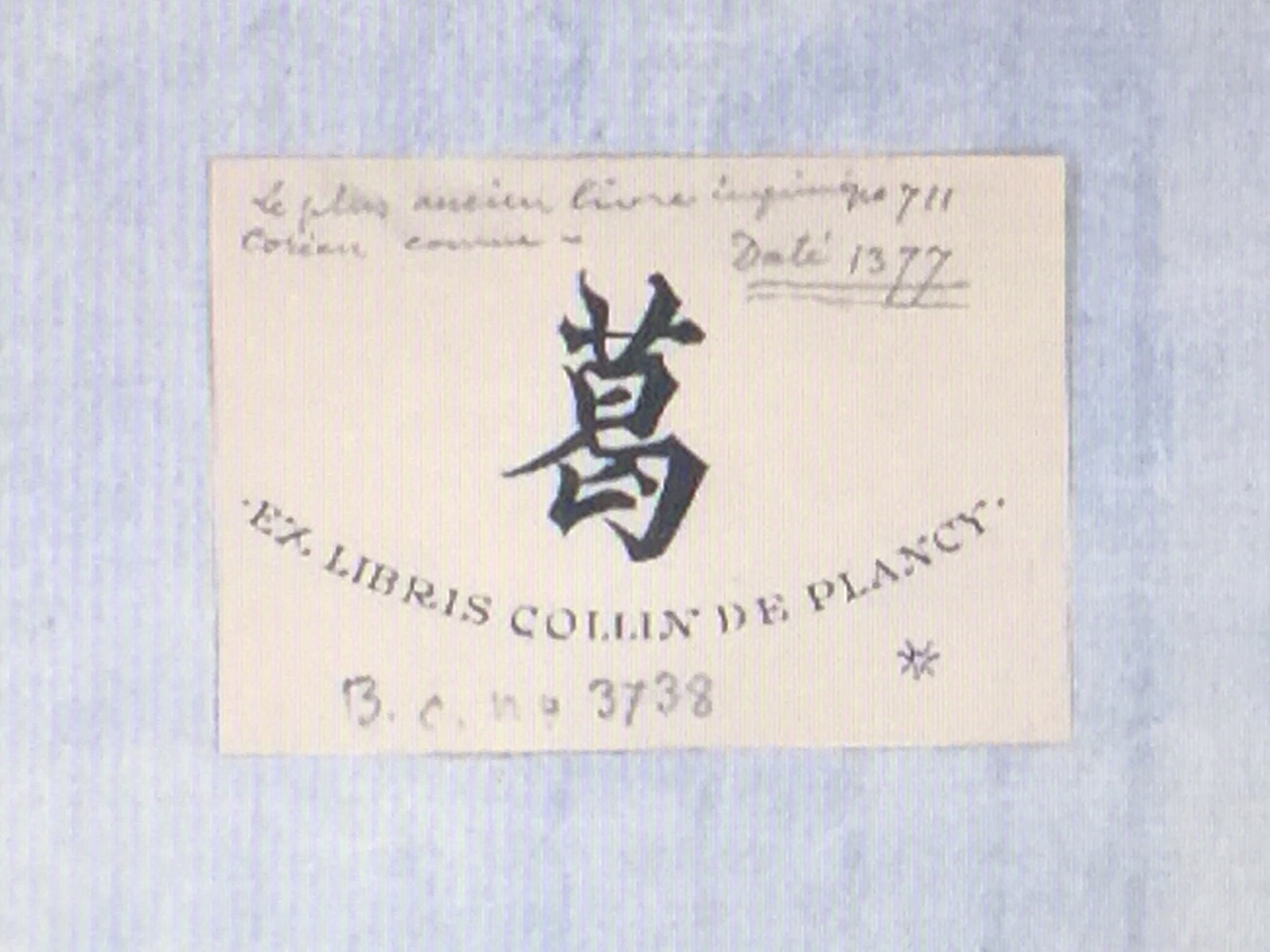

The objects she investigates do not have stable identities and signal the limits and limitations of official, sanctioned, or simply common conceptions and understandings of a phenomenon. One of the most compelling examples of Nam’s interstitial surveys can be found in Coréen 109. “Coréen 109” is the archival reference for Jikji which, according to its descriptor in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France’s catalogue where it is held, is “the oldest Korean book printed in characters [scratched illegible] melted 1377,” that is, the first book known to have been printed using movable metal type.6 Containing a collection of seminal Zen Buddhist sermons, dialogues, and letters compiled by Monk Baegun that predates Gutenberg’s printing of the bible by seventy-eight years, this first edition of the Buddhist anthology is a cornerstone in nationalist claims about Korea’s contribution to intellectual and printing history. Indeed, as Korea only possesses a version printed with wood blocks produced a year later, in 1378, several organizations have been demanding the restitution of the metal type printed edition to its country of origin, specifically the Early Printing Museum in the city of Cheongju, whose mission is to “widely promulgate the significance of Jikji” and which even features a Jikji pavilion in anticipation of the artifact's long-awaited return.7For artists working today whose work attempts to reflect on issues of cultural heritage, the currency of decolonial discourse within the contemporary art field and the acknowledgement of the necessity of repatriating objects appear as a paradoxical ally both offering a convenient conceptual shortcut for what they try to convey while at the same time short-circuiting and overriding their aims by simplifying it. In a recent conference about the restitution of African objects held in Western museums, Senegalese philosopher Souleymane Bachir Diagne reminded us that “we live in a Westphalian world, which means that we have nation-states. This implies that when we discuss restitution, whether it takes place within the framework of UNESCO or another setting, we are talking about international relations.”8 As put by Nam herself, “Coréen 109 was first shown in an exhibition on Korean print culture held by the Korean Cultural Center UK and the Korean Publishers Association.” In the film, she wanted “to approach the Jikji in a way that didn’t deal with questions of cultural property and their return.”9

As the story of Jikji goes, during the interval marked as the Korean Empire (1897–1910), the book was extracted from Seoul, its locus of origin, by the French diplomat Victor Collin de Plancy. Removed and re-inscribed into a different archive, it would eventually come into the hands of jeweler and Asian antiques collector Henry Vever and was later donated to the Bibliothèque nationale de France in 1950. Forward to the 2000s: when requesting to view Coréen 109 at the BnF, the institution referred Nam to the digitized document available online, the physical copy being accessible to “researchers only.” Faced with this obstruction, the artist set to retrace the journey of the book, a boundary object as it were, investigating the many gaps—temporal, spatial, conceptual—that shape its various modes of existence, as both physical object out of reach and as virtual one, omnipresent. As she put it herself, by retracing its trajectory, Nam “thought of collecting the time related to the book and its surroundings.”10 Notwithstanding the fact that recent research has demonstrated that other books printed with movable metal types have been found to predate Jikji, here, again, a choreography of thought provides an alternative paradigm. Nam does not offer a solution to the problem of provenance and repatriation. Collected, catalogued, and classified, Jikji-Coréen 109 also appears to be lost in preservation. Safeguarded, it remains suspended as spectral body, caught between the right to return and the right to remain a memory.

The Choreographic, Expanded

The intersection between dance as a medium, statecraft, the body politic, and the politics of the body constitutes a major terrain of investigation for Nam. Works like Throbbing Dance and Against Waves foreground propaganda, cultural identity formation, how choreography operates as a tool for nation-building, and how specific dance pieces act as political performance. Presented as a three-channel video installation, Throbbing Dance (약동하는 춤, yagdonghaneun chum) stages what seems to be the rehearsal of a contemporary dance performance in a dance studio. The piece is made of alternating shots of each of the three young female dancers performing specific moments of a choreography with sequences in which they dance together. Interspersed with these contemporary scenes is historical footage of a television dance show. Pixelated and at times unfolding in freeze-frames and emitting audible beeps, the interaction between the contemporary and archival footage progressively reveals that the former is a response to the latter. But this historical piece, as the soundtrack signifies, is a remake, the song the dancers perform to being none other than the 1980s pop hit Flashdance… What a Feeling (1983), cowritten and performed by Irene Cara. The version in the pixelated found footage was from a TV broadcast by North Korean musical ensemble Wangjaesan Light Music Band, known for its frequent media appearances where it mostly performed gyeongeumak (경음악) or “light music” in English and which in North Korea consisted in blending traditional Korean melodies with modern instrumentation. As scholars of the Democratic People’s Republic of Kora have noted, the hermit kingdom is a theater-state that stages its status, power, and governance through mass performances, public spectacles, art, film, museums, and monuments. Public culture serves as a tool of both propaganda and political indoctrination, reinforcing authority through orchestrated displays and repetitive narratives.11 In this regard, Throbbing Dance does more than trace processes of transcultural adaptation and appropriation. It interrogates how bodies participate in the making of state power and how identical or similar movements can be re-inscribed with opposing ideological meanings.

As curator Hyunjin Kim aptly observes, “while choreography usually is seen in terms of stage directions and movements within the genre of dance, we could have a ‘choreographic’ mode in an expanded sense.”12 Indeed, in Nam’s practice, the Korean, Asian, and World histories she explores unfold in their diversity and sensoriality. Finally, while state narratives lead to an organology of supposed total intelligibility, Nam’s choreography of thought articulates an organology of fragments and gaps, choreographing spaces where multiplicity, memory, and speculation are (re-)set in motion and rhythm, never quite staying in place.

A shorter version of this text was previously published under the title “Choreography Against Cartography: Three Movements on Nam Hwayeon” to accompany the exhibition ‘Hwayon Nam: Ripple’, 15 March–13 April 2025, Centre d’Art Neuchâtel, Switzerland. The author would like to thank Nam Hwayeon, Kyung Roh Bannwart and the team at CAN.

Jihoon Kim, “Inter-Asian Dance as Method, Artistic Research as Method: Nam Hwayeon’s Work on Choi Seung-hee.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 23, no. 4, 2022, 526–39.

As Peter Szendy writes: “I cannot, however, stop myself from lending an ear to other meanings in the name of this outdated figure: I also understand effiction as the contraction into one word of fiction and its power, of its efficacy.”[footnote Phantom Limbs: On Musical Bodies (New York: Fordham University Press, 2016) 15.

Choi’s dance practices were rooted in her innovative integration of Korean traditional forms with influences from Japanese, Chinese, and Western modern dance. Her career spanned complex geopolitical contexts, including colonial Korea, Japan, and post-war China and North Korea. She was accused of self-orientalizing her performances for a Western audience; of political alignment with North Korea, where she defected in 1946; and, having performed for Japanese audiences during the Japanese occupation of Korea, of imperial sympathies. For a discussion of Nam’s project about Choi, see: Jihoon Kim, “Inter-Asian Dance as Method, Artistic Research as Method: Nam Hwayeon’s Work on Choi Seung-hee.”

Naoki Sakai, “What Is Asia? On Anthropological Difference” in Mayumo Inoue and Satoru Hashimoto (eds.), Beyond Imperial Aesthetics: Theories of Art and Politics in East Asia (Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press, 2019), 201–18.

“Coréen 109. 백운화상초록불조직지심체요절. 白雲和尙抄錄佛祖直指心體要節. Päk un hoa sañ čʹorok pulčo čʹikčʹi simčʹe yočōl (1377)”, Bibliothèque nationale de France, →

“Cheongju Early Printing Museum,” →

Souleymane Bachir Diagne, “Objets africains ‘mutants’ et la question de la restitution,” YouTube video, 1:07:32, published by Musée d’ethnographie de Genève, 30 May 2023, →. My translation.

Hyunjin Kim and Hwayeon Nam, “Conversation with the Artist,” in Hwayeon Nam: Time Mechanics (Seoul: Arko Art Center, Arts Council Korea, 2015), 181.

Hyunjin Kim and Hwayeon Nam, “Conversation with the Artist.”

John Connell, “Tourism as Political Theatre in North Korea,” Political Geography, no. 68, 2019, 34.

Hyunjin Kim and Hwayeon Nam, “Conversation with the Artist,” 185.