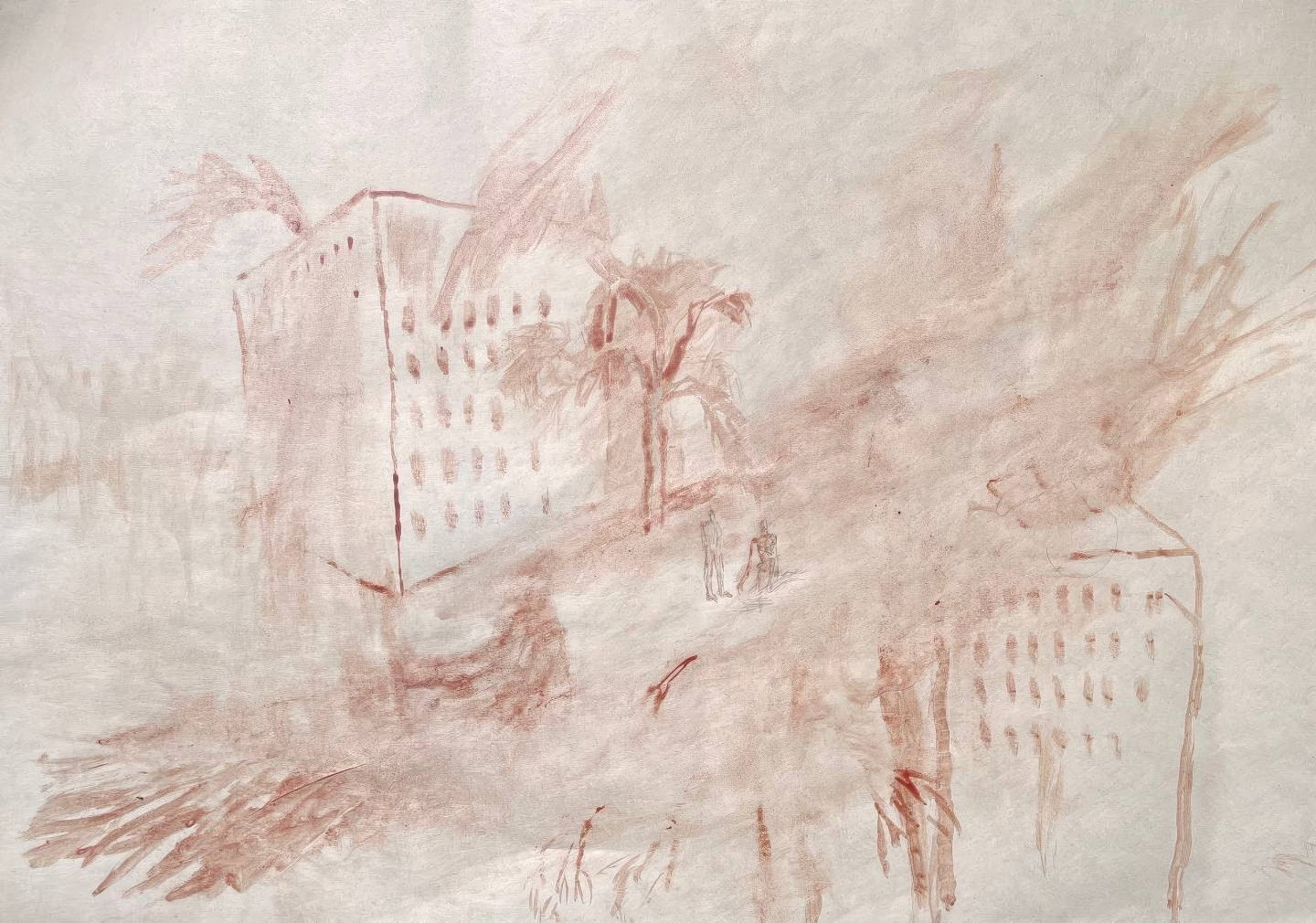

Still from Olha Zhurba, Songs of Slow Burning Earth (2024).

It would not be an overstatement to say that, after three years of full-scale war, it is becoming increasingly difficult for Ukrainian film festivals to survive. Among the few that have managed to withstand both the external blows of war and internal economic struggles is the International Human Rights Film Festival Docudays. Its twenty-second edition gathered seventy-one films from thirty-one countries, yet the attention of local audiences was directed mainly towards national cinema. Perhaps surprisingly, Ukrainian viewers exhibit a deep interest in war documentaries, despite experiencing countless narratives of war in their daily lives. On the opening night of the festival, Russia launched a massive drone and missile attack on Kyiv. After spending the night in shelters and even cynically joking that these were fireworks for the opening, the audience embarked on eight days of viewings.

In this report, I want to focus on two of the festival’s categories: the national competition, which presented artistic auteur-driven documentaries, and the “Ukraine War Archive.” The material in the latter category did not claim the status of film as an art per se, but it participated in an unofficial dialogue about the concepts, methods, and functions of wartime documentary and its representation of truth and testimony. Together, these categories upheld the conflict in Ukraine as the most documented war, and, consequently, as a remarkable cinematic phenomenon of modernity.

Only five films were included in the national competition. They highlighted the observational approach that has become a common language among Ukrainian filmmakers, as an almost existential struggle against the relativistic worldview gaining traction today. When the boundary between fact and fiction is constantly contested, when Russian propaganda offers a counter-truth to every fact, this struggle is essential. This approach is embedded in an intention to capture reality as it is, counterbalancing the rapid, edited images from news and social media that carry the aggressive indexicality of hyper-truth.

Kateryna Gornostai’s Timestamp is a vivid example of how a Ukrainian documentarian can adeptly select a niche subject for static, distant camera observation under the overarching reality of war. Gornostai, previously known for her coming-of-age school drama Stop-Zemlia, enters into a beautiful intra-authorial dialogue by producing a grand documentary about the education system during wartime. Chaotically moving across Ukraine, she captures astonishing accounts of extreme adaptability: from first-graders in Kharkiv attending an improvised school in a metro station, to pupils from occupied territories tragically graduating online. Amusing and harrowing scenes are accompanied by an experimental choir that sounds like both a cry and an inquisitive exclamation, while the storyline is rigorously contained within the boundaries of a full academic year. Thus emerges a collective portrait of the Ukrainian schoolchild—one that reveals the tragedy of mental lability as both a new reality and the foundation of a new generation. It’s particularly notable how Gornostai filmed on a large Alexa camera. Understanding that she cannot be a “fly on the wall,” she intentionally includes moments where the children curiously look into the lens. This approach reflects the director’s awareness of the observer’s dominant power over the vulnerability of children—and, as a result, avoids adopting the stance of a detached gaze.

Another film that seeks to express the human capacity for adaptability is the TABOR Collective’s Militantropos, whose philosophical concept is inscribed in the portmanteau of its title: “milit” (warrior), and “antropos” (human.) The synthesis of two ancient etymologies becomes a representation of a persona adopted by humans when entering a state of war. The TABOR Collective has spent over twelve years documenting the transformations of militarized Ukraine. Yet in their new film Yelizaveta Smith, Simon Mozgovyi, and Alina Horlova aim to instead depict a static condition. The film opens with footage from the onset of the full-scale invasion but quickly shifts to portraying militarization as an established, deeply rooted state of affairs, juxtaposing footage from the front lines and the rural realm. Yet the film lacks the emotional and temporal resonance needed to fully convey the condition it represents. The film proves more compelling in the way its raw registration of fields of rubble and its tightly filmed artillery operations are processed photographically. The frontline hyperrealism, characteristic of TABOR’s aestheticizing approach, produces an effect of horrifying beauty. For instance, when soldiers go on the offensive, the screen mimics the lens of a thermal camera. Though this visual effect is realized in postproduction, it serves as a reminder that observation is always mediated, and that the aestheticization of raw material can sometimes offer a more layered truth. Militantropos acknowledges that emotional and perceptual authenticity may necessitate a certain degree of artistic intervention.

In Olha Zhurba’s Songs of Slow Burning Earth, the central protagonist is the process of “normalization” itself—an invisible yet acutely felt phenomenon. Beginning on the first day of the full-scale invasion, the film opens with a frantic image of emotional terror: tight close-ups, a sharp audiovisual synchronization, and abrupt editing. But as the film progresses, it gradually drifts into prolonged abstraction: the frames become more distant, image and sound begin to desynchronize, and the camera deliberately turns away from the suffering. Zhurba once said to me that she had succeeded in documenting her own feeling of war normalization. Though her presence remains off camera, her personal sensibility becomes palpable in the brilliance of the editing. Through the composition of shots and the rhythmic logic of the tragic song cycle referenced in the film’s title, she manages to convey the drawn-out process of psychological deformation. Here, the film’s overt poeticism is a form of fictionalization that creates a sensation of reality that feels almost too surreal to be believed.

The emphasis on observational filmmaking in Ukraine points to the validity of Erika Balsom’s assertion that in silent observation and the distanced gaze, a vital trust in reality as such is rehabilitated.1 The national competition jury’s support for observation, poetics, and the richness of polysemic imagery—signaled by its awarding of the top prize to Songs of Slow Burning Earth—gives hope not only for the rehabilitation of faith in the documentary gaze, but also for the restoration of images to a position of trust, rather than merely being objects of critique and suspicion.

Two other documentary films in the competition represent a different niche of documentary practice. My Dear Theo by Alisa Kovalenko and In Limbo by Alina Maksimenko are deeply personal diaries. The directors, who are the main protagonists in their films, construct reflective essays on their positions at the heart of the war. Kovalenko builds her film around the striking intersection of her social roles: she is a soldier, a mother, and a Ukrainian. She films herself on the front line and, in a voice-over, reads letters she wrote to her son Theo. By showing profound vulnerability, Kovalenko constructs an uncompromising model: such raw openness becomes a kind of coercive test of empathy, where any doubt or emotional detachment on the part of viewers toward the social roles she embodies would constitute not only an offense against the filmmaker, but also against all those who share these roles.

Maksimenko, in her film, presents herself as less heroic but no less emotional. She confronts the full-scale invasion with a cast on her leg, in the town of Irpin, near Kyiv. Miraculously escaping on one of the last evacuation convoys, she retreats to a nearby village where her parents live and begins her video diary. The domestic atmosphere gradually intensifies as Russians approach the village, yet her parents decide to stay in their home. Maksimenko films staged conversations with her mother and her father’s nervous breakdowns in a way that often feels uncomfortably intimate. In In Limbo, the very process of documentation becomes a way of existing within reality. In both films, truth does not function as a mirror but rather refracts reality through a deeply personal lens, leaving almost no room for distance or critical dialogue.

The other part of the festival—the Ukraine War Archive—expanded the dialogue around the boundaries of documentary cinema, both as an art form and as a document in its most literal sense. The Ukraine War Archive occupied one of the screening rooms—not on screen, however, but on a stage. Entering the room, visitors encountered eight booths with laptops that had access to a massive database of photos, videos, and audio recordings amounting to 280 terabytes. “When history is questioned—evidence answers,” declared the banner at the entrance. Opening the interface, users were offered filters to sort files by location, date, and type of media evidence (from CCTV to talking heads), or by an extensive menu of war crimes—many of which, like “sexual crimes” or “kidnapping,” are less visible crimes.

Overwhelmed by the sheer scale of the archive, I decided to go personal—I filtered for my hometown, Sievierodonetsk in Eastern Ukraine, occupied and almost completely destroyed in June 2022. While watching videos of the residential buildings on my street being bombed, I came across some unique recordings that were not accessible through Telegram channels. I found myself unable to look away—likely because I still cannot fully believe that this tiny peaceful town, which in my psyche had only positive connotations, has now been raped by the Russian invasion. It began to feel like this form of audiovisual documentation—so fragmented and of such low quality—was the most real and uncompromising of all. Precisely because of its (non-)accidental authorship, it carries the indexical trace of a collective tragedy, and thus one that is immeasurable. The Ukraine War Archive is also, perhaps, one of the most extraordinary databases available for the film industry. A volunteer explained to me that all rights to the files remain with their original providers, and the Ukraine War Archive serves as a mediator to facilitate access for filmmakers. This room contains an inexhaustible resource for multimedia cinema, adaptable to any storyline.

In parallel, the festival also presented an entire War Archive section; its status as an artistic exhibition was not sufficiently communicated by the festival, but it could contextually be interpreted as a demonstrative display of database cinema. These films often resembled journalistic OSINT investigations rather than traditional cinematic storytelling. One such example was Bucha. Yablunska, a sixty-four-minute film that in real time reconstructs war crimes committed by Russian soldiers as they advance along the main street of Bucha.2 Composed from phone footage and CCTV recordings that the Russian troops, through their own negligence, and to the benefit of Ukrainian intelligence, failed to disable, the film not only lays bare the full scale of these crimes but also identifies the perpetrators. Yet the invaluable resource that almost glows with its own aura is the bravery of the civilians who, with trembling hands and at great personal risk, captured war crimes on their phones. These “poor images,” to use Hito Steyerl’s term, carry enormous power, not because of their quality but in spite of it. The loss of visual clarity here takes on a political density, preserving the trace of an event whose truth is assembled from fragments, and whose communal nature once again renders the tragedy global.3

Technology here is not subordinated to the ideal of objective documentation, as in observational documentary, but rather reveals the potential of personal witnessing as a form of resistance—shifting the focus logically toward human rights. This, in essence, is the central theme of this year’s Docudays. And yet, all forms of witnessing—whether the silent observation of war, confessional self-reflection, or straightforward war-crime testimony—embody paradigms of truth that use every cinematic and emotional tool at their disposal to shape the beliefs of the viewer. Belief is essential for holding onto any sense of grounding amid this war, and is so urgently needed today, at a time when the war crimes committed against Ukrainians both behind and in front of the camera are at risk of being forgotten or devalued.