Viktor Timofeev, Alice, Bob, Carol and David (still), 2024.

On May 27, 2025, e-flux Screening Room presented a screening of select works by Viktor Timofeev that was followed by a conversation between Timofeev and Ericka Beckman and by a Q & A with the audience. The transcript of this conversation was edited for the present publication.

Ericka Beckman (EB): To begin, I want to say how wonderful it was to see your latest film Alice, Bob, Carol and David (2024) projected on a large screen, especially with the accompanying soundtrack: the amplified sound, graphics, color, movement, and overall composition were remarkable. When you first shared this film with me I immediately had a strong reaction. I was intrigued by how it adopts the premise of a game yet deliberately avoids direct gameplay. Instead, it functions almost as a narrative blueprint—it sets up conditions and suggests possible outcomes, but intentionally leaves out explicit character development and a concrete plot. By presenting only behaviors, constraints, and movements, it creates a fertile space for imagining multiple stories. It even struck me that the format of ABCD as an overhead schematic of David’s struggles to influence and gain attention of the other characters could actually be used as a pitch for developing a full narrative script—as a graphic plot outline—although that’s clearly not your intention. I’d like to return to the topic of narrative shortly, but perhaps first, Viktor, you could share a little about your background and what led you to use game engines in your artistic practice.

Viktor Timofeev (VT): Thank you, Ericka. Before I respond, I want to quickly say that it’s genuinely an honor to speak with you—your work has profoundly influenced mine. I am from Riga, Latvia, and have most recently been living in New York. My current practice evolved through several stages, initially rooted in drawing, which I still deeply appreciate and engage with. At some point, however, drawing alone stopped feeling like the right medium for me. I shifted towards experimental performances, sound-based projects, and nonlinear websites, exploring labyrinthine digital structures that allowed open-ended and ambiguous navigation. When I encountered game engines, I immediately recognized their potential to engage directly with the concept of agency, something I was particularly interested in exploring. At the time, I was experiencing episodes of chronic pain, and game engines allowed me to communicate this feeling of loss of control I felt over my own body. I couldn’t identify another medium capable of addressing this idea as effectively.

EB: To clarify the chronology—I initially assumed you started primarily with game engines and then moved into drawing, but it was actually the other way around!

VT: Exactly. Initially, I was deeply invested in drawing. In fact, my first aspiration was to become an architect.

EB: That makes sense—architectural influences clearly show in your work.

VT: Yes, certainly. But architecture didn’t ultimately work out for me. I was particularly drawn to visionary architectural ideas rather than practical design, which I am not very good at.

EB: I’d like to discuss your creative process because your work clearly emerges from observation-based studio work. For example, your use of mechanical toys involves observing their behaviors, reflecting on them, and then constructing barriers to challenge these behaviors—as if designing for a three-dimensional environment. You also have extensive experience with drawing, painting, and other studio practices that have evolved alongside these explorations. Could you speak about the progression from the Hexbugs experiments (2016) through Continuum (2017) and ultimately to Alice, Bob, Carol and David?

VT: Regarding the progression, it initially began casually—I wasn’t necessarily thinking about exhibitions or films. I found these vibrating mechanical toy bugs called Hexbugs which have this one fundamental behavior: when they encounter a barrier, they turn either left or right. When I placed several together in a confined space, their behavior became surprisingly complex and somehow also relatable. It fascinated me how simple rules could lead to intricate interactions, and how the human mind can assign meaning to observed behavior, especially when dealing with something it doesn’t fully understand.

Viktor Timofeev, Hexbugs (still), 2016.

Regarding the Hexbugs, I began experimenting with creating flexible, irregular barriers for them, filming these interactions initially just for myself. I was interested in seeing how slight variations in boundaries could influence group behavior—how a critical mass of bugs could collectively shift the entire structure that contained them in a new direction. This exploration eventually turned into an exhibition at Jupiter Woods in Vienna, partially documented in the Hexbugs video. During the three-hour-long exhibition opening, the bugs’ batteries gradually depleted, providing a kind of natural narrative arc from liveliness to near immobility.

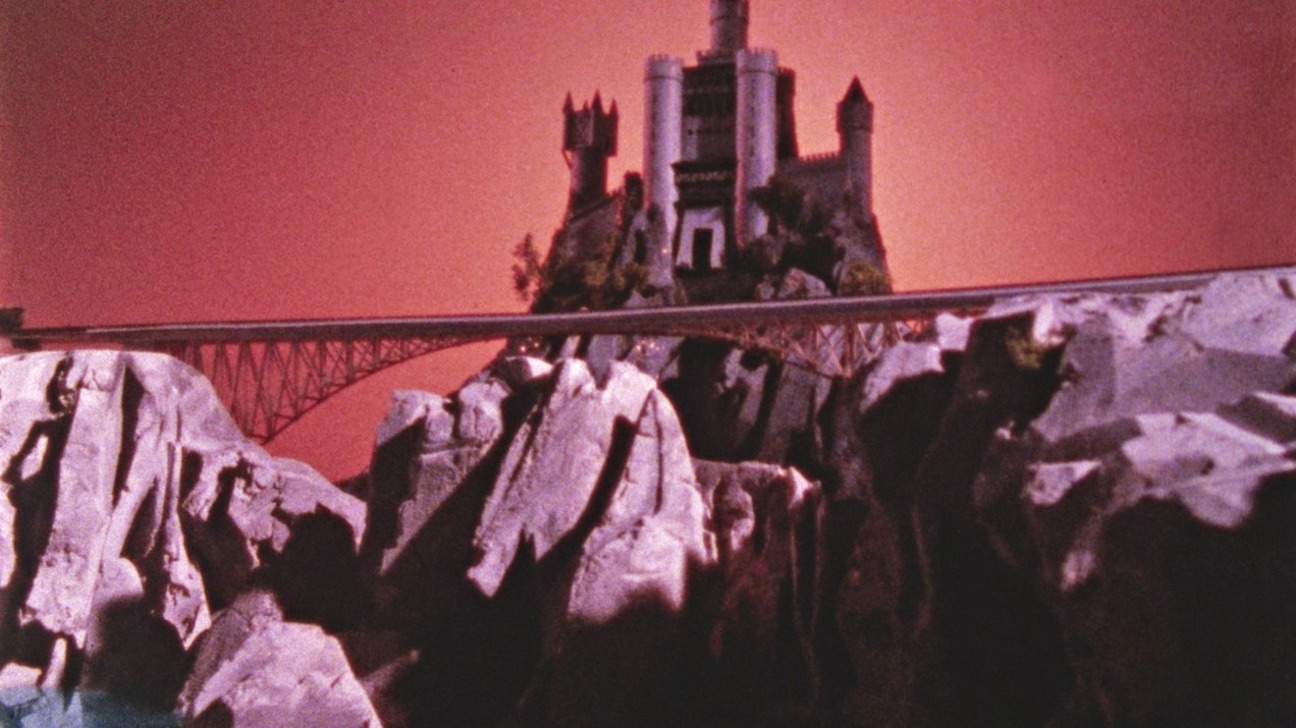

From there, my experiments evolved digitally. Working in a game engine, I programmed virtual cockroaches that expanded on the mechanical bugs’ behavior. They would either turn left, right, or turn around when encountering an object, all with degrees of probability and variety. They would also pause occasionally to “think.” I put a bunch of these virtual cockroaches in an empty environment and started filming them in the same way I approached the Hexbugs—waiting for something interesting to emerge. I filmed them using an orbiting, virtual camera, something akin to a God’s-eye view. Months of this kind of play eventually wound up sowing the seeds for Continuum. While I was looking through my footage, the story started writing itself—who was doing the observing in this environment? Who was operating the virtual camera? The virtual camera that was looking down at the world became the second character, a drone. The basic premise became this switching of perspectives between the two characters. It was all “shot” from their first-person point of view, alternating between them, the ground and the sky, the observer and the observed. Continuum is my first film made using a game engine.

Afterwards, I reused the cockroach assets to develop a VR game about cockroaches, partly to confront my personal fear of them—interestingly, spending significant time with virtual cockroaches did help alleviate that fear.

These experiences, particularly playing around with first-person points of view of the cockroaches and spending so much time in VR, ultimately led me to giving each virtual cockroach its own subjective environment—their own virtual virtual realities, or worlds only they could perceive. I designed a system where their movements and interactions responded to these hidden stimuli, their internal worlds. Gradually, I replaced these insect-like entities with humanoid characters, resulting in the creation of the four characters—Alice, Bob, Carol, and David. Their basic movements, in fact, trace directly back to those initial mechanical Hexbug experiments. More experimentation and several versions later led to the final film, Alice, Bob, Carol and David, that we screened here today.

EB: I’d like to discuss how you script movement. I’m not a coder, but my assumption is that you translate physical movement directly into code—is that correct?

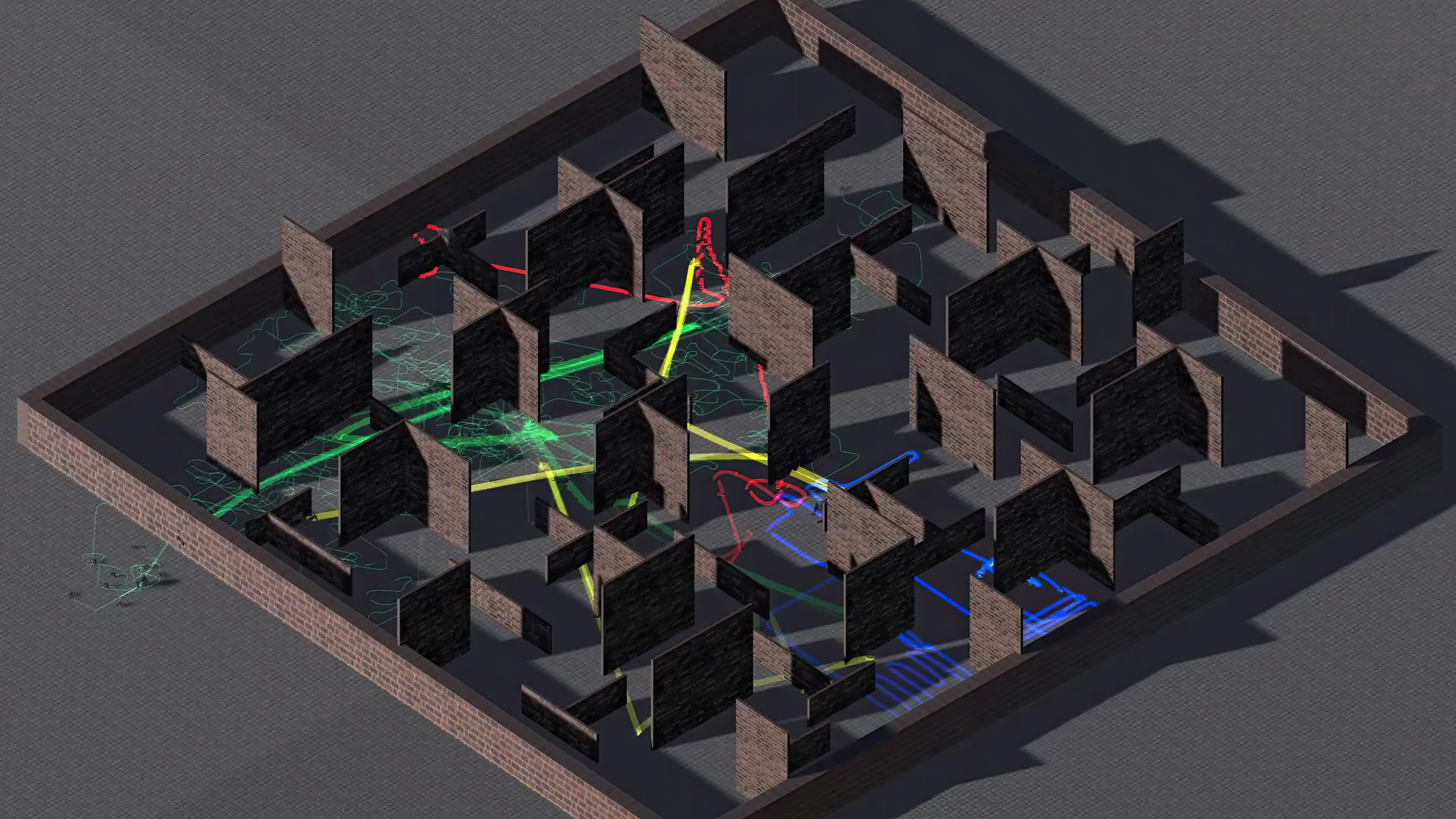

VT: Yes, exactly. Movement became central in Alice, Bob, Carol and David, where the four characters together create a kind of choreographed chaos. Each character moves differently—one strictly at 90-degree angles, another at 45-degree angles, a third that follows alternate versions of itself to form more organic, fluid paths, and a fourth character combines elements from all of the others. Collectively, their movements become a dynamic collective drawing in space, orchestrated purely through behavior. Each movement has its own distinct logic and intention.

This became more obvious once I visualized the characters’ paths in space, assigning a different color to each one.

EB: You mentioned earlier that certain movements strongly resonated with you personally. When observing the Hexbugs, you selected movements you identified with or felt connected to. Beyond analyzing timing and spatial positioning, is there another language—abstract or otherwise—that you translate these movements into, perhaps something that could later evolve into another form?

VT: Early in my experimentation—around the time of the cockroach projects—I saw an inspiring exhibition by Yvonne Rainer at Raven Row in London that featured her 1970s performances. I was mesmerized and kept trying to decode the choreographic scores, but I never fully managed it until right before each performance ended. It became clear that Rainer’s choreography involved complex layers of call-and-response and chance, elements I wanted to understand and incorporate into my own practice. What struck me profoundly was watching performers follow hidden instructions or cues—almost as if they responded to an invisible reality. This concept, together with Rainer’s drawings of movement paths, deeply influenced my thinking. I sought to capture a similar quality in my own work: movements motivated by an invisible logic. I did also make quite a lot of abstract drawings playing around with meandering lines as speculative paths guided by rules, both in anticipation and in response to the Alice, Bob, Carol and David film. Eventually, I’d love to work on a live action choreography—maybe an operatic piece, complete with elaborate costumes—that brings these ideas into a physical performance. This is still in development, but translating these virtual choreographies into tangible, performative scores is an ongoing fascination.

EB: Do you keep some sort of log or notebook of movements that resonate with you personally, something you’d like to explore further?

VT: The movements that Alice, Bob, Carol and David perform outside of pure locomotion are sourced from their main function: they are actually zombie game characters. I bought them readymade and they already came with these sets of zombie-like movements. I assume their main intention was to be used in some kind of survival or horror game. But once I removed them any props they came with from that context, the movements became ambiguous and pretty strange. I made a chart of all of their “non-zombie” behaviors and combined these together until something interesting started to happen, and that became the choreography that underpins the film.

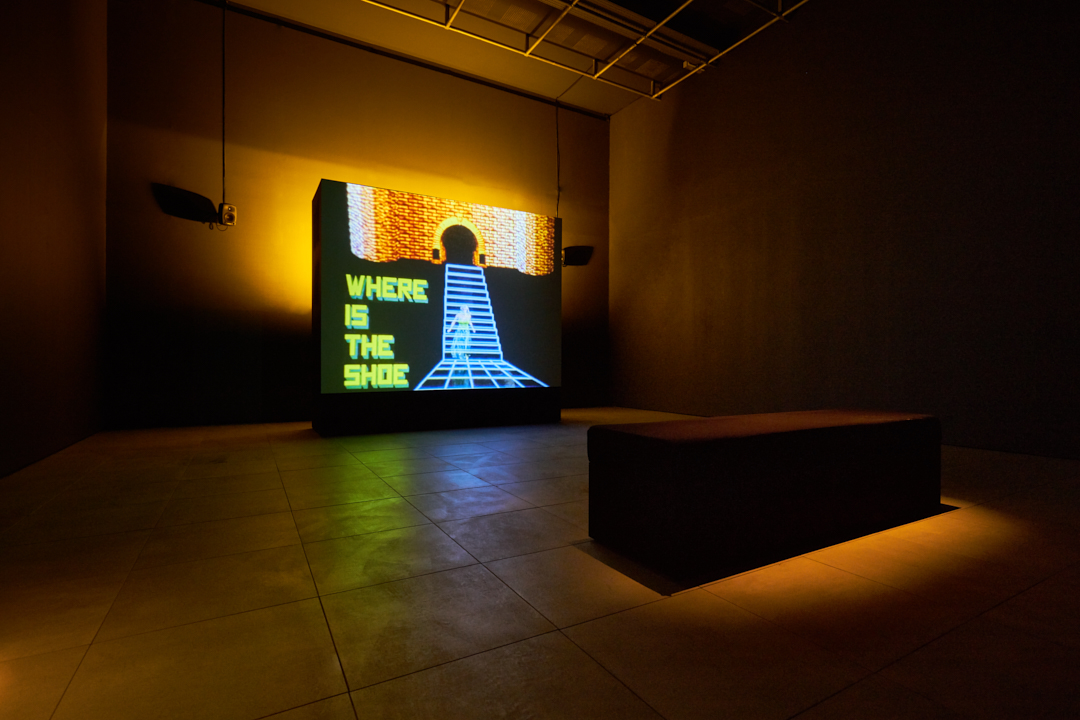

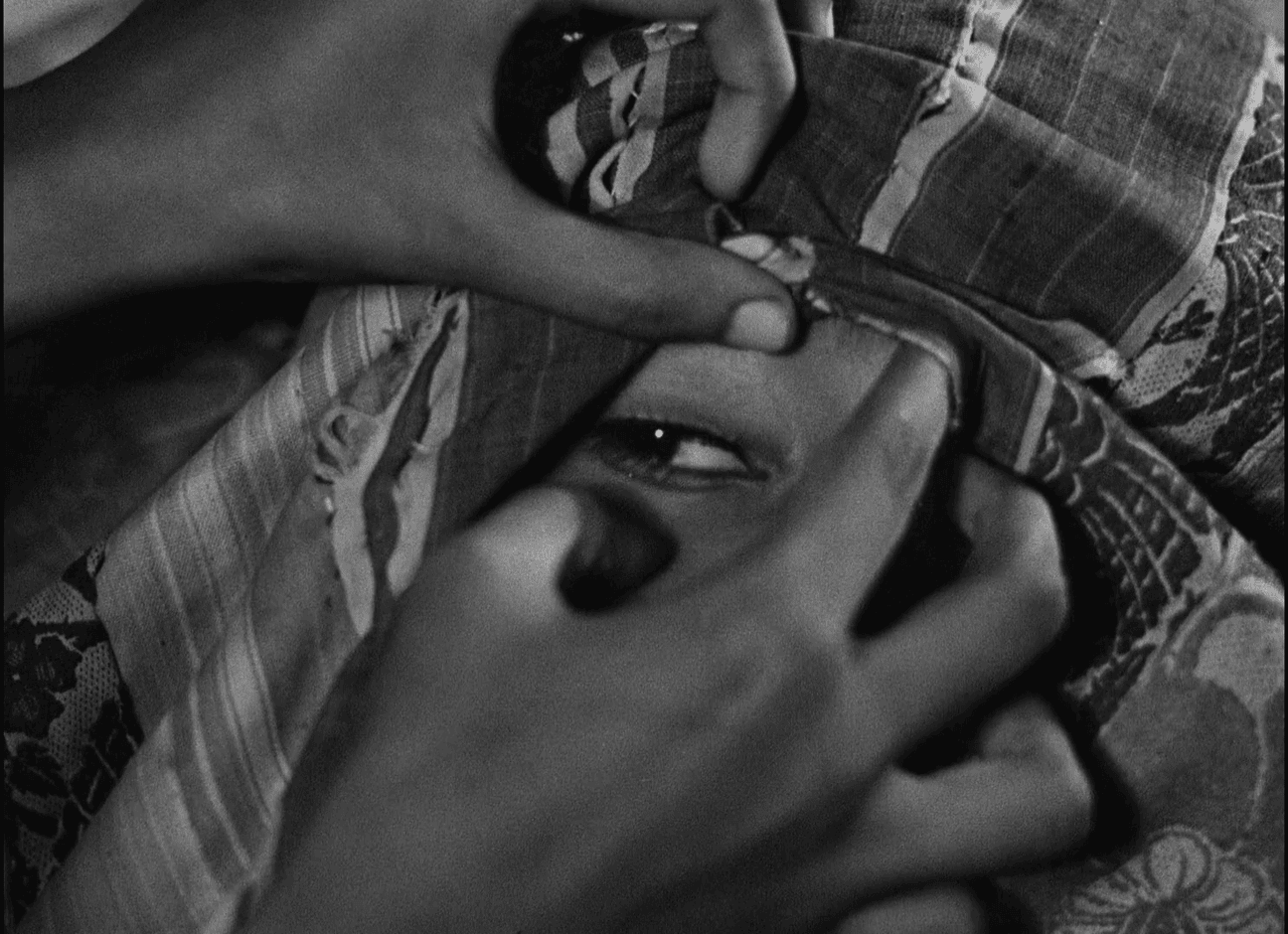

EB: You mentioned earlier your fascination with creating alphabets and languages. Could you elaborate on how these experiments evolved into your recent piece, Chat (2021)?

VT: The Chat piece evolved from a larger installation at Interstate Projects in New York that included a mural, drawings, and a three-channel video component. I’ve been developing the alphabet concept behind Chat for about eight years now. Initially, I wanted to create my own writing system—not just random shapes, but something systematic and fluid, unfolding over time. An alphabet that exists in time. I imagined it as observing language evolution from a geological timescale, capturing how letters and associated meanings mutate and transform.

Early experiments involved systematically scrambling parts of individual letters or blending fragments of multiple letters together. When I first showed these experiments to friends, each person associated them differently—some saw Japanese, others Russian, and others imagined fictional languages or even alien scripts. This hybridization, situated between language and chance, resonated deeply with my personal experience of language. Speaking English, Russian, and Latvian myself, I’ve become increasingly aware of how each language evokes a distinct sense of identity, almost a different personality. This trilingual combination is typical of my generation in the post-Soviet Baltics. I’m still exploring how language constructs identity, so abstracting and “othering” familiar alphabets feels both personal and universally intriguing.

In the single-channel version of Chat that we saw tonight, the English alphabet continuously mutates, shaping the dialogue between two figures. The dialogue is written using the same dynamically changing letters, so the work presents both the cipher and the ciphertext at once. This interplay underscores my interest in the fluid boundaries between language and perception.

EB: This reminds me of our earlier conversation about your experiences moving between the US and Latvia, both as a child and as an adult. I’m particularly fascinated by your use of clocks in your work. Clocks regulate our lives collectively, providing a shared orientation point. We use time to mark where we are in space. But your work abstracts this concept, altering the familiar relationships between major and minor dials and translating those changes into texts we can’t decode. The viewer, confronted with this abstraction, naturally begins projecting personal meanings onto the shifting symbols. Your clock series seems to move beyond the psychological into more philosophical territory. Could you elaborate on where you’re taking this idea next?

Viktor Timofeev, Chat (still), 2021.

VT: Certainly. To provide some context first—I emigrated with my family from Latvia to the US, then moved back to Europe, studied there, and eventually returned to New York. Now I am spending more and more time in Latvia again. Latvia has always held special significance for me; regularly exhibiting there has been particularly meaningful. Recently, I had a solo show at the Latvian National Museum featuring a clock-based installation, which is currently still on view.

Regarding the clock work itself—initially, I experimented with many ways of arranging the alphabet, including grids and lines, but none were fully satisfying. When I positioned letters onto a clock face, it instantly created a relatable form that albeit is also kind of unfamiliar. Given that my alphabet is continuously moving and evolving, the clock became a natural and symbolic format.

Over the past few years, I’ve created many versions of the alphabet clock. Inspired by the endless variety of clock faces in the world, I’ve experimented with different shapes, typefaces, pacings, and evolution mechanics. The most recent version, made for the Malmö Art Museum, was a “kid’s version” that focused on just the first four letters—A, B, C, and D. It combined mural painting and video, which started to move into sculptural territory. That feels particularly exciting and I would love to get deeper into this route—I’m thinking clocktowers!

Looking forward, I’m also interested in exploring handwritten interpretations of these evolving letters. I’ve experimented by asking friends to quickly sketch the fleeting forms, capturing them as they rapidly shift. Everyone has a different take because everyone has a different bias. There is something potent about this misinterpretation that feels like interesting territory. Because these letters maintain horizontal symmetry, they appear letter-like yet remain elusive and fluid. My recent exhibition in Latvia integrates a handwritten letter using these abstracted alphabets. Viewers might briefly decode the letters by mentally “freezing” the shifting forms, though complete decoding remains practically impossible. Still, observers intuitively sense an underlying grammar or structure, which I think is equally important as the letters themselves. I want to keep exploring this direction—moving further into performative and theatrical territory.

EB: Your clock pieces suggest interactivity or at least hint toward interactive possibilities. Historically, there have been artists who disrupted language or created new languages to alter how communities communicate—I’m thinking particularly of the Lettrist group from France in the 1950s. They created a new spoken language across performance, film, and writing to change the politics of interaction. I am also thinking of Guy de Cointet in the ’70s, who wrote in code and used performance to break it down for the audience. In both cases the idea was to subvert dominant narrative structures. Does your work aim for something similar?

VT: To some extent, yes. I’ve staged performances where instructed performers “translate” an encrypted text. For a set period of time, they write out tables of semi-abstract letters on gallery walls or even on their own limbs, consulting an ever-changing alphabet clock in the process. I thought of these performances as a kind of mediated interactivity: the audience is offered a guide to how the system works in real time. My hope was that viewers could later engage with it themselves—a form of interactivity similar to reading time from a clock.

Your question also reminds me of a 2015 show in Riga—the first time I tried making an interactive installation and told myself I’d never do it again. I wanted to provide written instructions but struggled with the language: English felt inappropriate, Latvian risked excluding Russian speakers, and trilingual instructions seemed cumbersome. I settled on pictograms, and in the end, of course no one understood them. While I liked that everyone shared this confusion, I didn’t want it to seem like I alone held the key. To eliminate that hierarchy, I introduced randomness in the next generation of my alphabetic experiments, which later became my alphabet clock—making it impossible even for me to fully grasp the content. In that sense, the alphabet clock became my way of dealing with interactivity: a self-playing game that only exists when there’s an audience to witness it.

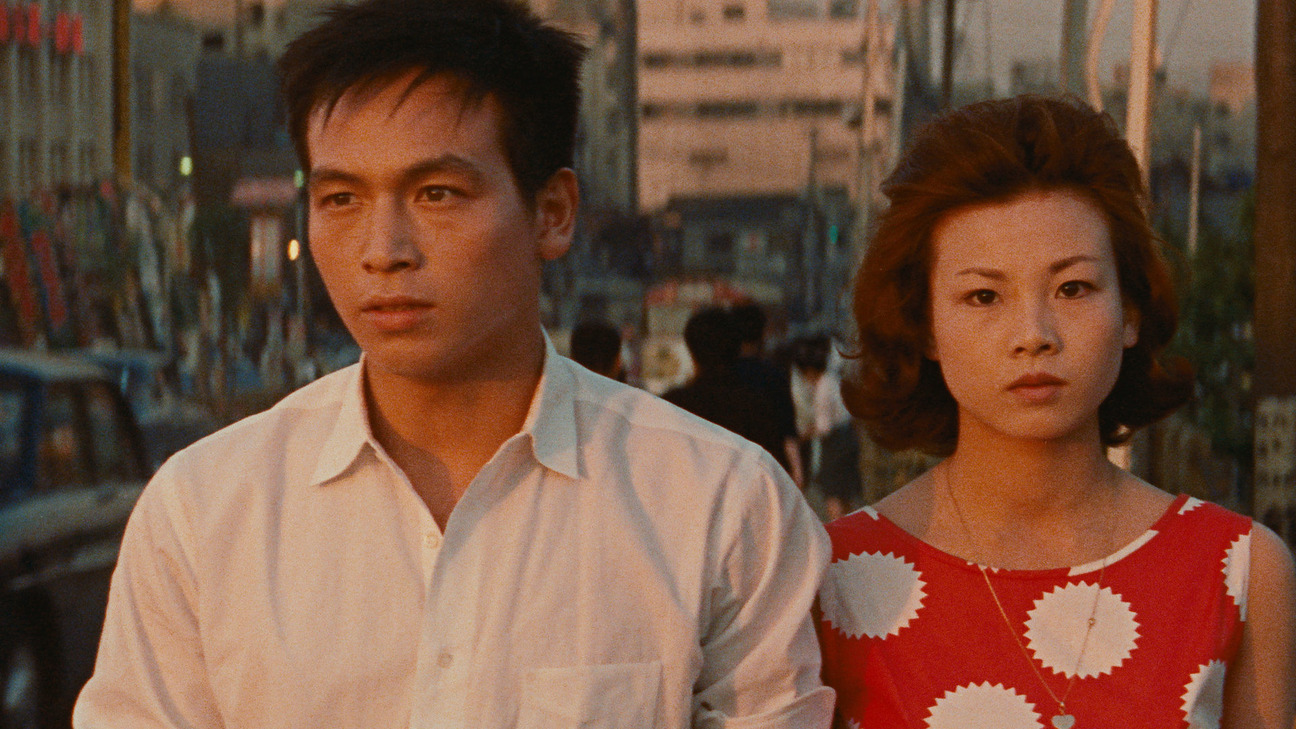

EB: I’d like to briefly return to Alice, Bob, Carol and David. Previously, you mentioned it was partially inspired by an early television play. Could you elaborate on that inspiration—perhaps your interest in Samuel Beckett’s work? Additionally, you described your studio process as very layered. In this piece, you gradually incorporated cinematic techniques—such as editing, voice narration, and altering the soundtrack. Did these cinematic elements emerge to enhance the final recorded gameplay, or were they influenced by your observations of character behaviors?

VT: The cinematic elements, especially voice narration, emerged toward the end of a long developmental process. The first version of Alice, Bob, Carol and David was a two-channel, infinite duration simulation, with two perspectives of the world side-by-side—a first-person and third-person view. In this version, the characters performed a randomized choreography in ten minute loops that was always different and also always kind of the same. But because randomness and probability were involved, there were some great moments but no guarantee that they would ever repeat, which was sometimes a bit frustrating.

When a friend invited me to document the choreographic score of the piece for rtru.org, an online platform, I filmed the whole “gameplay” from inside the game engine editor using a virtual camera, diagramming and annotating the interactions step by step and character by character. This process revealed a narrative clarity that felt very different from the original format. I gradually became much more interested in relating to the conventions of cinema rather than games or simulations. That led me to experiment with adding voiceovers by friends and family, assigning each character a personal dimension through these familiar voices—including my father and filmmaker Ken Jacobs, whom I assist. This step was crucial to humanizing a piece that previously felt overly mechanical. I think this tension between the inhuman and the personal was what connected me to Beckett—especially his television play Quad (1981), which reminded me of the mechanical toy Hexbugs.

I worked with Miša Skalskis, a Lithuanian artist and composer, on the musical score, which added an overall arc to the whole thing, culminating in a very dramatic climax. I realized that it’s very hard to get people immersed in something that has an infinite duration. Maybe that sounds obvious but I suppose I had to arrive at that conclusion on my own time. I also owe a lot to my friend, artist and frequent collaborator Jaakko Pallasvuo, who strongly encouraged the whole piece, suggested working with Miša, and helped me edit the dialogue. We collaborated on the video drawing piece we screened tonight, Artificial Life and Death (2022).

EB: That’s fascinating—I haven’t approached computer-based work in that way myself. Did observing the autonomous gameplay inform your understanding of how these characters could interact more humanly?

VT: To some degree, yes. Initially the characters were just Character 1, 2, 3, and 4. As I gave them names, I started to get attached to them and to develop something like a backstory for each one—why they do what they do—even if I never made that public. Because the characters’ lifeworlds are a take on Maslow’s pyramid of needs, I wanted to make it easier for an audience to identify with them and relate to their worlds. As I captured, edited, and cropped the characters’ “performances,” a fixed duration and a focused edit became a much better way to tell this particular story. I started to think of it as if I was documenting one special rendition of a play and subsequently editing this documentation for an audience that couldn’t attend the performance.

EB: I remember feeling particular empathy for David. Poor guy—he seems overlooked.

VT: Yes, though actually, everything depends on David!

Audience member: Viktor, could you elaborate on the opera you mentioned you are working on—with an orchestra and performers?

VT: It’s still very much in progress. My original idea involved creating a live action play inspired by the alphabet clock piece, with twenty-six performers dressed as letters moving in choreographed patterns. The complexity of designing costumes and working in a medium I have never worked with has kind of stalled the project, but I hope that will change soon!

Audience member: Following up on Ericka’s earlier question about the voice actors in Alice, Bob, Carol and David: you mentioned your father was involved. Did you give him and the other participants room to interpret the characters, or did they strictly follow your script?

VT: They mainly read from the scripts I provided; it wasn’t deeply collaborative in terms of character development. For example, my friend Evita Vasiļjeva, who often discusses existential topics with me, naturally read Alice’s part. My father and Ken Jacobs, who I am helping produce his Eternalisms series, also contributed their voices, though we didn’t deeply workshop the texts together. The resulting ambiguity was somewhat intentional—I welcomed the personal interpretations the voice actors brought naturally to their roles.

Audience member: Your works we saw seem to repeatedly emphasize interaction—often ambiguous or incomplete. The clock piece has characters speaking without clear mutual comprehension, and earlier we saw figures failing to perceive each other, as well as mechanical insects briefly coupling before separating again. Does this reflect a broader perspective you hold on interaction—perhaps that connection is fleeting or inherently limited?

VT: That’s definitely a recurring theme. I’m drawn to setting conditions and observing what emerges naturally—whether it’s dropping toy bugs into an enclosed space to watch their spontaneous interactions or mixing letters into abstract shapes, trusting that complexity emerges from simple rules. I’m fascinated by how minimal guidelines can produce intricate behaviors and outcomes. Maybe it’s something of an obsession…

Audience member: Following up on that, I’m interested in how you position humanity in relation to the artificial or mechanical entities in your work. Often it feels like humans are constructed or constrained similarly to these other entities, following certain rules or game-like systems. Could you speak more about this?

VT: I think this connects directly to some of the inspirations behind my recent work, particularly Alice, Bob, Carol and David. I was influenced by the 1961 Twilight Zone episode “Five Characters in Search of an Exit,” itself derived from Luigi Pirandello’s play Six Characters in Search of an Author (1921). Both works depict characters searching for their identities and purposes. There is also something to be said about the comfort of systems. I think this is a bridge into my drawings and installations. I often work with constraints and self-imposed rules in order to harness the tension between order and disorder, improvisation and structure. I think this comes from a personal history of migration and a search for the feeling of home.

I’m intrigued by how many struggles people experience remain completely invisible to others—conditions like chronic pain, which I’ve dealt with myself. Art became my way of managing this hidden pain and ultimately led me to working with game engines. For me, games uniquely explore ideas of agency and unpredictability. I often imagined a game whose rules change randomly every minute, metaphorically conveying the uncertainty I experienced daily. I tried to channel this in Proxyah (2014–15), my first game, the playthrough of which we screened tonight. This idea—the hidden, internal worlds we inhabit and others can’t see—has profoundly shaped my practice.