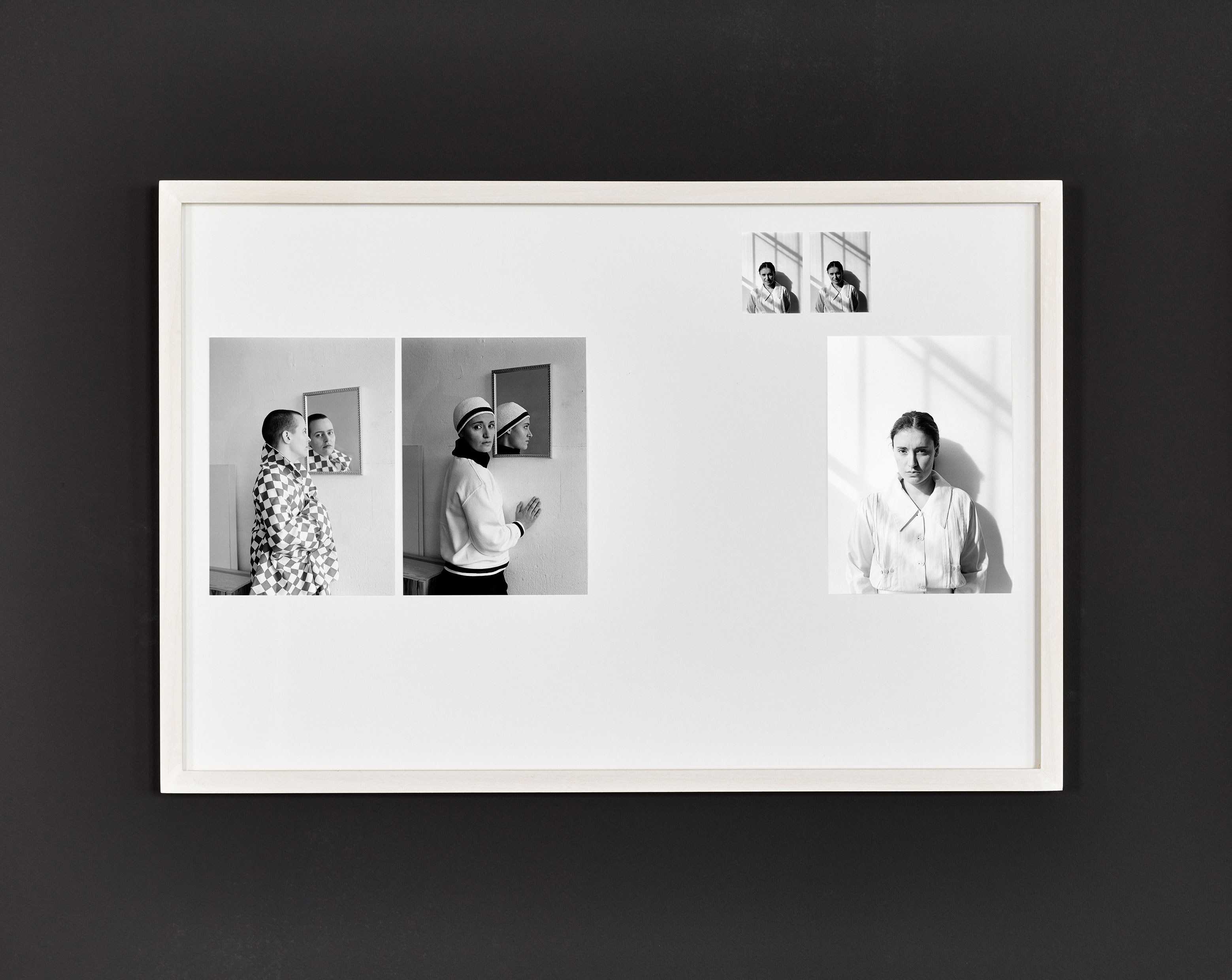

But what does vulnerability actually mean? Is it being able to acknowledge a state of pain or insecurity, embracing the feeling of coming undone? I feel that it’s something I’ve tried to hide from others and from myself. At the cost of headaches, a bloated stomach, the inability to articulate a sentence. A mental-physical feeling of paralysis. I now suspect that people spend a lot of time and effort hiding in this way. Could I overcome my terror of falling apart if I allowed myself to rely on others, on you? Or should I be a “cruel optimist” and create hopeful and positive attachments, in full awareness that they will not work out?

Closeness

The Covid-19 pandemic forces the human animal to practice isolation. In proximity, our bodies expose one another to the chance of perishing. To stay together, we must now remain apart. We will, to be sure, meet again. But what will closeness, relation, and community mean to us then? What, we begin to wonder, did they ever mean? As we distance ourselves from the social, perhaps we gain an opportunity to find out.

Let the following selection from the e-flux journal archive be a starting point for discussion.

View List

View Grid

9 Essays

One divides into two, two doesn’t merge into one. This was an old Maoist slogan from the 1960s. Despite its air of universal truth it has become dated, and I fully realize the danger of appearing dated myself by starting in this way. Nowadays, one can recite this slogan in front of a class full of students and none will have ever heard it or have any inkling as to its bearing or its author—it’s almost like speaking Chinese. The slogan combines an ontological statement, a mathematical theorem, an...

The night after Donald Trump won a long and ugly US presidential race, Alain Badiou entered a classroom at the University of California, Los Angeles, sat down, placed some notes on the table, and then explained that he had decided not to give his planned lecture, “Concerning Violence.” Instead, the most prominent French philosopher of our day would talk about Trump and what his success revealed about our current political, historical, and economic condition.

The resulting lecture, which ran f...

There are more pressing matters than this potentially touchy matter of pressing close. The following story isn’t so much an apology for intimacy or some kind of championing of it, but rather the modest suggestion that intimacy organizes our experience of space and especially of surfaces. As such, it is in fact not so trivial or delicate after all. These are notes towards a reconceptualization of intimacy in light of new ways in which we can think of the surface.

1. Iridescence

Iridescence ...

1.

Recently I found myself at the Clark Art Institute in Massachusetts, standing in front of an orientalist image. Together with a colleague I was looking at The Slave Market by Jean-Léon Gérôme, painted in 1866, only one year after the official abolition of slavery in the US. The caption of the painting said the following:

A young woman has been stripped by a slave trader and presented to a group of fully clothed men for examination. A prospective buyer probes her teeth. This disturbing...

This is a segment of conversation between the philosopher Bernard Stiegler and cultural theorist Irit Rogoff that took place on the occasion of Stiegler’s lecture series, “Pharmaconomics” at Goldsmiths in February, March 2010, as part of his current professorial fellowship. In this segment, we touch on a couple of Stiegler’s key terms in the development of his thought, such as “transindividuation,” “transmission,” and “long circuits.” In his three-volume work Technics and Time, Stiegler has argu...

For some time, I have been interested in developing an anthropology of the otherwise. This anthropology locates itself within forms of life that are at odds with dominant, and dominating, modes of being. One can often tell when or where one of these forms of life has emerged, because it typically produces an immunological response in the host mode of being. In other words, when a form of life emerges contrary to dominant modes of social being, the dominant mode experiences this form as inside an...

In Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, two men wait by the side of a country road for a man who never comes. If done right, that is to say, if done with humor, fortitude, and a whiff of desperation, the play is as contemporary, funny, precise, courageous, and unknowable as I imagine it was back in 1952, when the play premiered in Paris.

When I worked with others to stage Godot in New Orleans in 2007, we took many liberties to make it work at that place, for that moment in time. We set the ent...

And pairs that cannot absorb one another in meaning effects

Go backward and forward and there is no place

—Lisa Robertson, “Palinodes”

No one lives in the future. No one lives in the past.

The men who own the city make more sense than we do.

Their actions are clear, their lives are their own.

But you, went behind glass.

—Gang of Four, “Is It Love?”

Over the past few decades, it has often been said that we no longer have an addressee for our political demands. But that’s n...