Compulsion

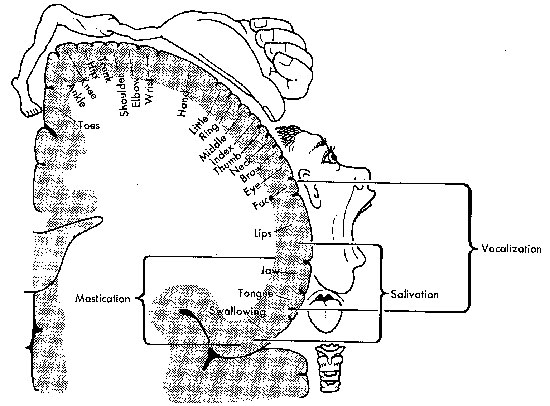

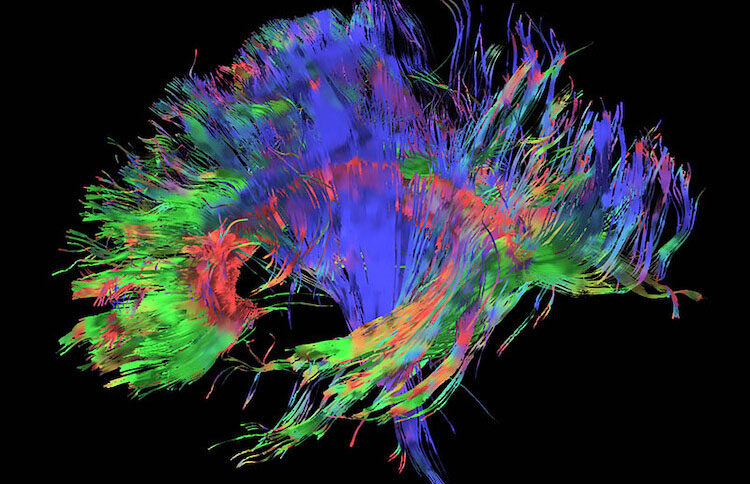

Medieval chronicles describe several episodes of an inexplicable epidemic running across Europe, with hundreds of people dancing involuntarily and unstoppably, sometimes for months. Considered at the time to be driven by supernatural forces, the dance plague is understood today as a form of mass hysteria or collective mania, a bodily expression of distress in the flesh of the laborers, following outbursts of black death and famine that were too deadly to be dealt with rationally. These phenomena speak of the known role of trauma and pose questions on the still unclear consequences of the current pandemic on mental health.

In this impersonal multiplicity, there is no one. What does this “no one” mean? It means a structural impossibility for “one” to be. A comrade is never alone—not in the trivial sense that there is always someone else around, but in the more radical sense that you are always many. You are Legion. This is how you succeed in “the fine art of not getting arrested,” persecuted, or burned alive by the inquisitors of your age. When you are many, you turn your back to the police officer and disappear. Comradeship creates a shield against the witch hunters who will try to catch us one by one, but who will never destroy the whole set of alliances that make up the Great Sorcery International. You know what I mean.