In one of his treatises, Malevich writes about the difference between artists and physicians or engineers. If somebody becomes ill, they call a physician to regain their health. And if a machine is broken, an engineer is called to make it function again. But when it comes to artists, they are not interested in improvement and healing: the artist is interested in the image of illness and dysfunction. This does not mean that healing and repair are futile or should not be practiced. It only means that art has a different goal than social engineering.

Untimeliness

Transformative undertakings are more often than not untimely. Yet despite this problem of always starting in the middle of things, transformation is possible, and it is regardless necessary to fight against the determinism of the moment in which one lives. But there is another sense of untimeliness: having no place in the contemporary moment—a neither/nor. Such a negative position begs an a-teleological and de-instrumentalized understanding of time and place. Each dying moment must pass into the new, and those intent on fixing the hegemony of their age forever are destined to fail.

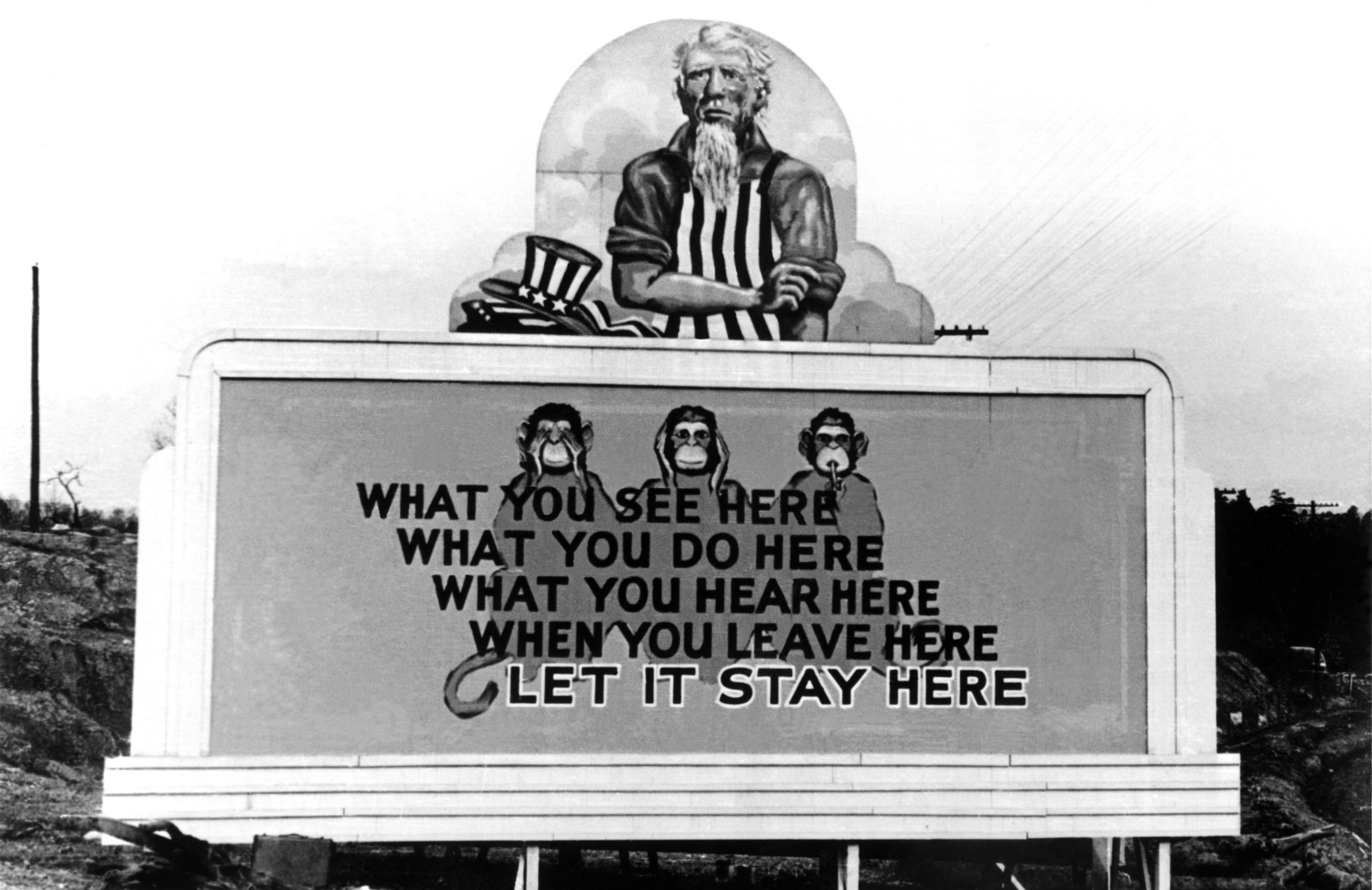

The day after I submitted my portfolio of afterwords, introduction included, George Floyd was murdered by a police officer in Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States of America. We were in the year two thousand and twenty. Time split and the two timelines we were now living shook violently. We were living a pandemic and a global uprising at the same time. It was hard to say what you were saying because every new day brought an incalculable change to your world and to your language. You didn’t know Norway would get involved. You couldn’t have imagined the Minneapolis city council would actually vote to dismantle its police department. You went to sleep and when you woke more people had gathered, more change had happened. One day all of Instagram was a flow of vivid black empty tiles, an act that took up more space than it made. White people began pulling from their shelves crusty books written by black authors and saying, “Read this” or “Follow this person.” Everyone who was anyone was saying, “Black Lives Matter,” but inadvertently were saying, “Some black lives matter,” which was all anyone ever said anyway.

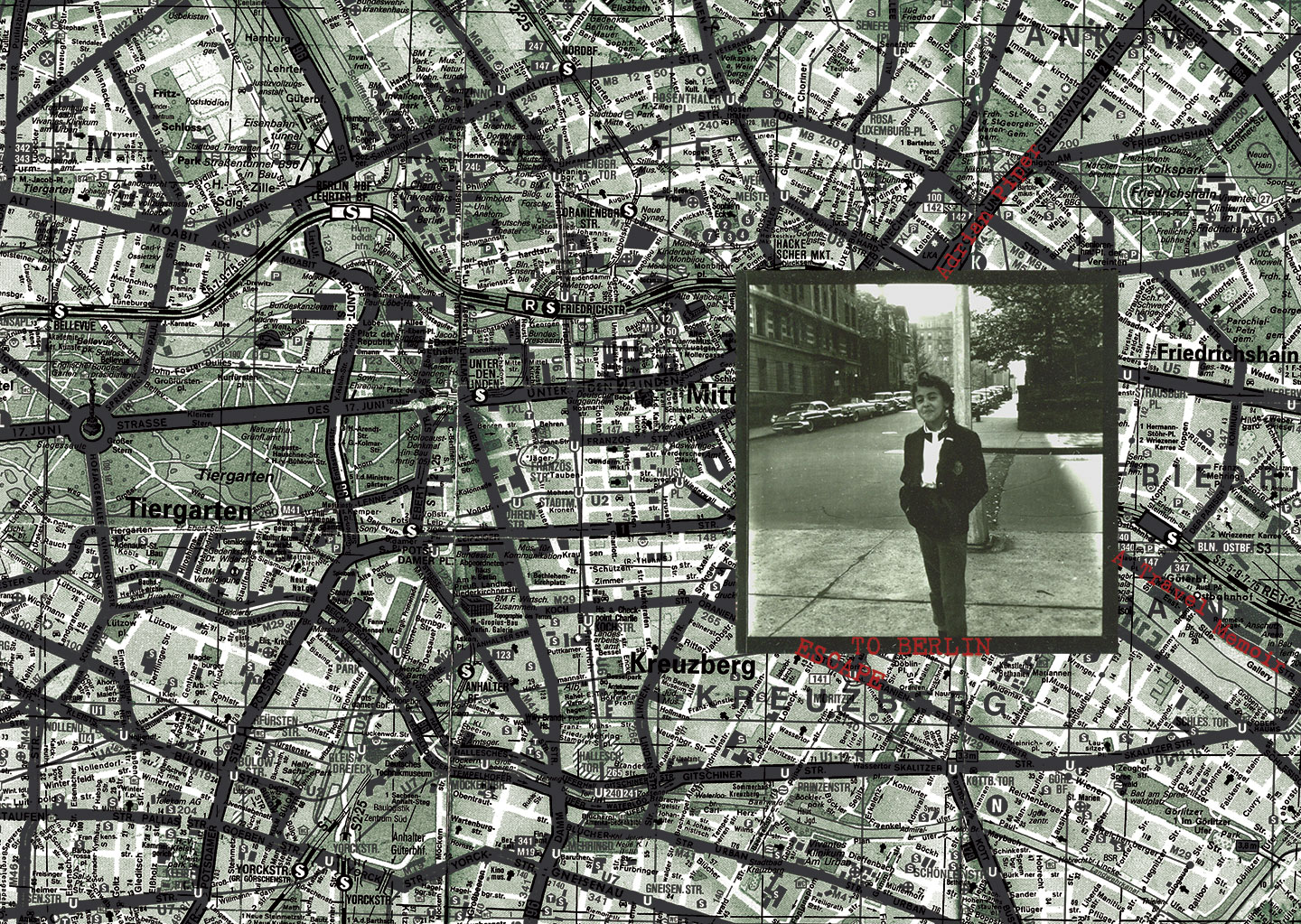

“Everything will be taken away,” depending on the context, takes on different meanings, but it is always with the same underpinning: loss is always occurring, but there is also a sense of relief at being able to let go of attachments. Piper’s memoir allows you to read very concrete meaning into this in regard to her professional affiliations in US academe and the US art world: being abandoned by all those depicted in the erased snapshots made it easier for her to leave behind the country from which she has taken exile.

I like to use Aladdin’s lamp as a simile for what happens in the art world. Artists make their work as they would make lamps: in the hope that the genie is inside. Sometimes they even believe that they can control the presence of the genie. Museums then display the art-equivalents of the lamp, betting, not just hoping, that the genie is in there and will stay there for the foreseeable future. The genie is intangible while the lamps are not, so attention tends to focus on the technical execution of the lamp, hence the emphasis on crafts and finish, or, after Duchamp, on how well they were intellectually framed as objects capable of containing the genie. The genie is in the lamp because museums say so, and the canon is the measuring stick with which they validate their statement.

Supposedly, one of the many “functions” of art is to heal the ruptures of history, and to “puncture” a whole in the membrane of the future, so as to render its advent felt in the present. In other words, artworking is to invent the sense of a shared time, across geographical expanses and ideological divides. How come today’s art, or philosophy, doesn’t achieve this? The underlying question is: How come “art” or “philosophy” doesn’t prevent violence? Ultimately, artists and philosophers are reproaching each other for the failure in solving problems that belong to the fields of medicine, education, political science, architecture, history, design, engineering, psychology, anthropology, genocide studies, etc. Is it only art or philosophy that fails in the face of the Rwandan genocide? Haven’t politics, technology, science, journalism, and the list is endless, also relapsed? What aspect of living doesn’t face its limit under such marks of death? I have no illusions that mere philosophers, or artists, are able to save the world! Why reproach the inadequacies of entire societies solely upon the ethics and the aesthetics of two cultural bodies?

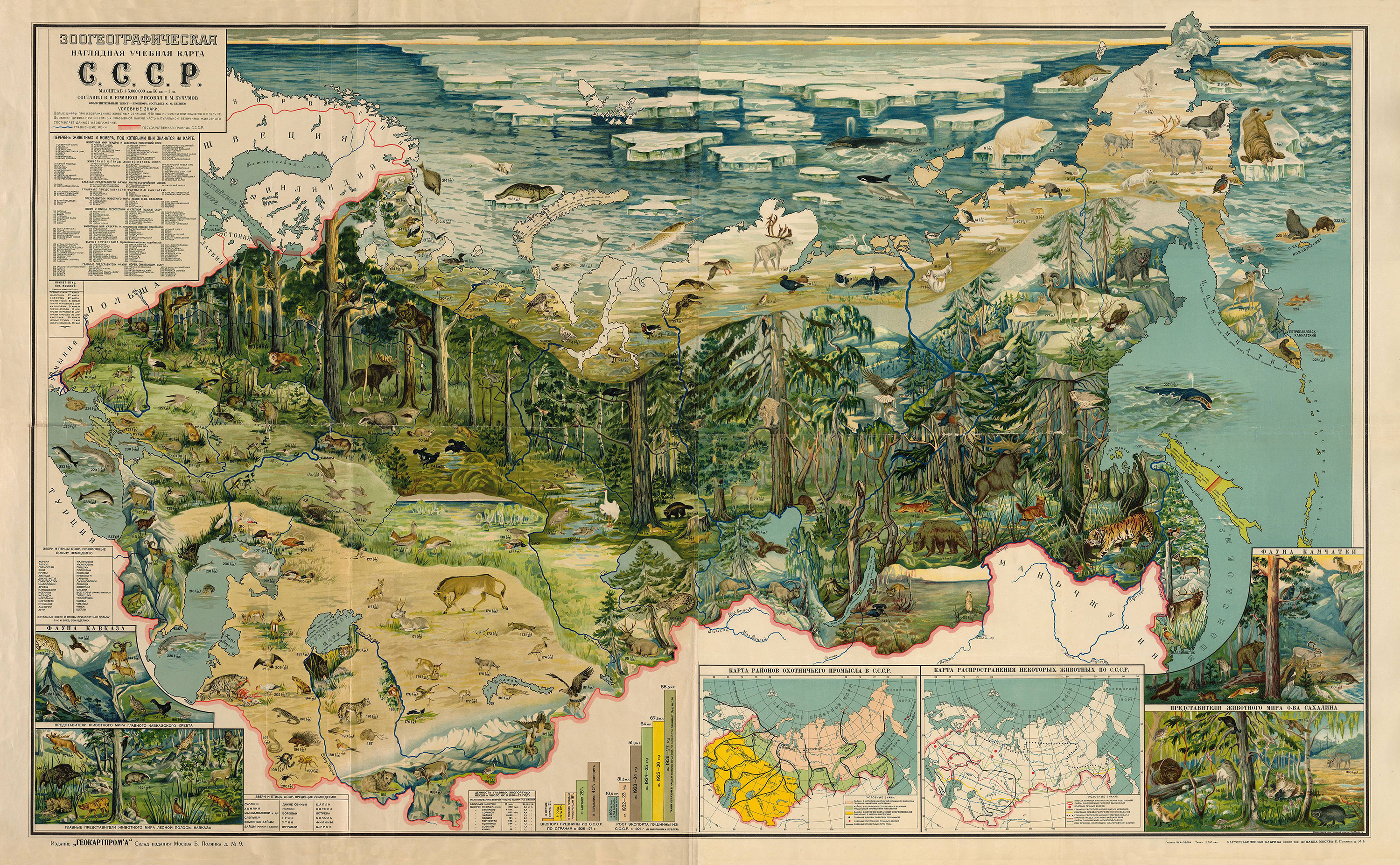

If Dhalgren shows us the crumbling of consumption in a capitalist society, Stalker portrays the collapse of the whole mechanism of production in a state-socialist one—symmetrical disintegrations that reflect the respective priorities of the rival Cold War systems. The collapse in Stalker goes beyond industrial production, which was the raison d’être for the Soviet planned economy as a whole—represented in the film by rusting equipment, warehouses that now store nothing but wind-sculpted sand—extending to the production of knowledge and meaning, the exhaustion of which is portrayed by the Writer and the Scientist. When all the machinery of the state-socialist system begins to seize up, what rationale or guiding principle can sustain people from one day to the next, let alone in decades to come? This is a moral crisis, to be sure—but a systemic, rather than an individual or personal one.

Can we resurrect the people who have not been born yet, but who nevertheless died prematurely due to environmental devastation, hunger, racism, and inequality? Perhaps by learning from Fedorov to think about time as a landscape—one that we shape in the same way that we shape the earth’s surface—we can develop a framework for thinking some of our most urgent crises.

Cosmists regard progress not as a goal or an end in itself, but rather as a necessary sacrifice that is an integral part of humanity’s struggle to survive and evolve. Real development, they believe, can only begin after humanity triumphs over death and learns how to resurrect the dead. This vision suggests that the future becomes the reconstruction or restoration of the past, and the arrow of time bites its own tail.