I’ve lost all my pride

I’ve been to paradise

And out the other side.

With no one to guide me,

Torn apart by a fiery wheel

Inside me.

—The West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band’s “I won’t hurt you” (1966), heard in Laida Lertxundi’s Vivir para Vivir / Live to Live (2015)

In LA, everyone’s Marlon Brando’s gardener. Cruising through a city sold and resold as a promised land, we’ve nothing to guide us but our passions for prosperity, for fame, for space, for spirit. All of us here somehow find a place in the end, even if it’s only as workers in others’ gardens, Edens owned by those that cast our dreams in moving pictures and the developers that sell or rent us our own smallest bite of paradise.

Made in L.A. 2016 is almost explicitly not about Los Angeles, though the city’s still the set.

Everyone likes to look in the mirror sometimes, and a localist biennial has some vanity for sure, but the city’s self-regard (Los Angeles again playing itself, to riff on gay porn auteur Fred Halsted through cine-essay maker Thom Andersen) has been finally outpaced by others’ regard for it. Such biennials can easily be read as a trend report for outsiders, emerging and under-regarded artists working in Southern California being the Hammer Museum’s specific rubric for Made in L.A. “New. Art. Now.” read the signs around the city for the show’s first edition in 2012. A massive curatorial team and a scatter of venues left one feeling more like LA was a mess rather than a movement. The most recent chapter, in 2014, curated by Michael Ned Holte and Connie Butler (the latter taking over from the late Karin Higa), was a genuine attempt at regarding the transformation of the city and its art community still stumbling out of the Great Recession and in the early stages of a massive influx of newcomers (as well as rampant real estate speculation, which is now at its highest pitch). The earliest announcements for Made in L.A. 2016, curated by the Hammer Museum’s Aram Moshayedi and the Renaissance Society’s Hamza Walker, were characterized by their non-statements about the show, and here the work appears unified primarily by a certain curatorial elegance and the loose fact that all of these artists, some only very recently, lived in Southern California.

In his catalogue essay, Moshayedi makes a sincere effort to describe a hazy set of contemporary conditions: a “Clouded Vision” of pot smoke, of the weird cultural need for likability and conspicuous experiences, how completely fucked we all are by racism and inequality. In this, Aram Saroyan’s poem as the subtitle for the exhibition “a, the, though, only” feels all the more fitting. Here are some things, singular and plural, placed under stated conditions but not explicitly connected to them. The artists of Made in L.A. are all certainly dealing with what it means to be alive in this place, but what those conditions are appear individually rather than curatorially defined.

A city, a space, and finally a set. Set-up, set piece, movie set, take your pick. So what does it mean to be here in LA, to be anywhere?

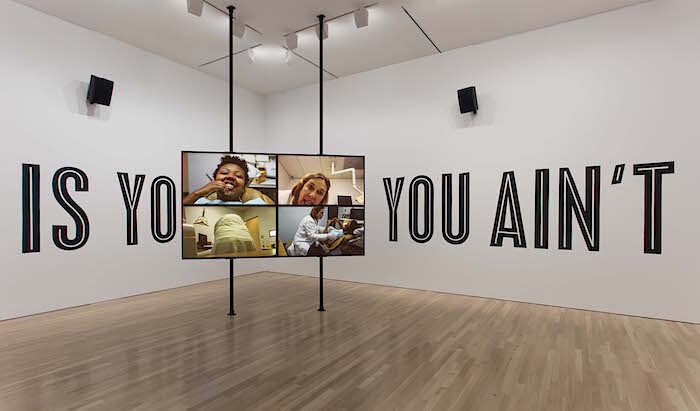

The curators of Made in L.A. 2016 say in The New York Times that they did not intend to focus the exhibition on Hollywood and modes of popular culture, but Walker is also quoted as saying that the reporter Jori Finkel’s observation “makes sense given the porous nature of the artworks we were thinking about—where music, fashion, film and poetry all rub shoulders with visual art.”1 The entertainment industry and its methods however emerge as one of the few clear themes in the exhibition. It appears in Margaret Honda’s Color Corrections (2015), a feature-length film consisting only of the color corrections of an unknown Hollywood feature; Daniel R. Small’s installation Excavation II (2012-16), in part following his excavation of the ruins of Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments (1923) in the sand dunes of California’s Central Coast; and filmmaker Arthur Jafa’s notebooks, Notebooks (1990–2016), which observed “a decidedly black aesthetic” drawn mostly from magazines (not seen by their compiler as an artwork) and presented in vitrines. Martine Syms’s Laughing Gas (2016), a kind of television show called “She Mad,” follows the travails of a young, black female artist played by herself, while writer Sarah-Lehrer Graiwer’s catalogue contribution takes the form of a television script called “Extended Trailer for The Unprofessionals” (2016).

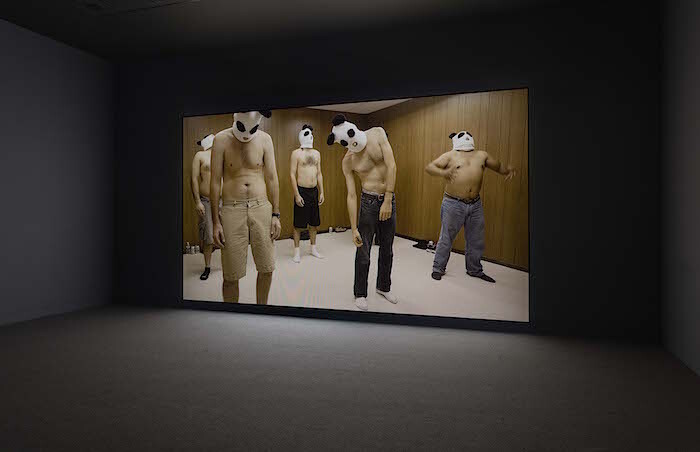

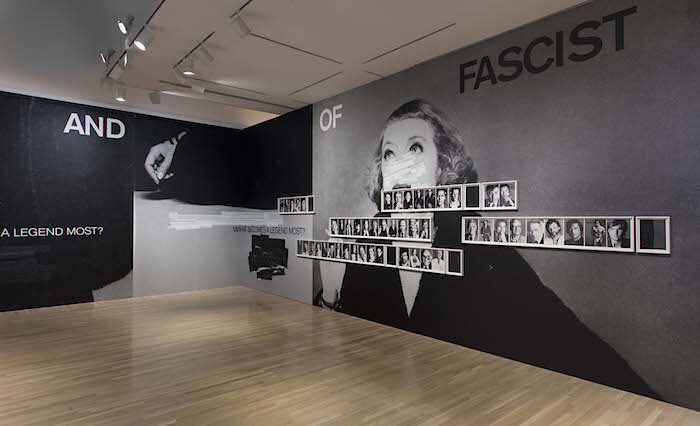

All this casts the biennial’s other works in a certain light. It makes Silke Otto-Knapp’s large, lovely grisaille landscape, Seascape (with moon) (2016), in the Hammer lobby a kind of set painting, the ropey hang of Kelly Akashi’s sculptures Eat Me (2016) like soundstage accoutrements or props. Shahryar Nashat’s moodily lit installation around a video of a kind of orificial love affair, Hard Up for Support (2016) and Lauren Davis Fisher’s periodically shifting “topographical stage” in Set Tests (2016) act as sets all their own. Kenneth Tam’s creepy video Breakfast in Bed (2016) about a faux men’s support group is clearly invested in the artificiality of the set the men find themselves on as well as the absurdity of their actions (as performed by amateur actors). And for his performance Ray (2014–15/2016), Todd Gray will, in his everyday life for run of the exhibition, wear his friend (and The Doors keyboardist) Ray Manzarek’s clothes, a template for its own reality show about embodying a celebrity on a deeply personal level. The borders of entertainment of course have clearly lost any sense of precision in the world, evidenced by Syms’s previously stated self-characterization (perhaps jokingly) as a “conceptual entrepreneur” and biennial artist/poet Dena Yago’s membership in K-Hole, which describes itself as a “trend forecasting group” with a list of corporate clients that includes MTV, Coach, and Stella Artois. (The latter evidences a kind of complicity I don’t really understand but that still fills me with a despairing kind of sadness.) Or that an actual brand, the fashion company Eckhaus Latta—curiously included in large city-based surveys of both New York (PS1’s “Greater New York” in 2015–16) and now Los Angeles—has, as part of their contributions to the biennial, a handful of garbed mannequins and an advertising campaign video, Smile (2016), including artists and an art dealer, both in the form of an online video but also tucked like ads in fashion magazine throughout the catalogue. In an installation deconstructing and recasting fashion ads from the 1970s with feminist quotes in Marxism and Art Beware of Fascist Broism (2016), Mark Verabioff’s dark glamor and raw political humor handles the presence of fashion in a much more critically aware and satisfying series of works. Many have argued that at this moment that we are all just managing our own brands in an entertainment industry that sprawls and octopuses into the most intimate aspects of our lives. I understand this mindset to be true for many, even as I reject it.

What do we do with the pieces —both artifactual and human—from fractured communities when the slick juggernaut of imperialism and capitalism smashes them to splinters? The recovered objects from Small’s cinema-set excavation mark a fluid disposability of the fragile falsity—and even weirder authenticity—of pop culture. Not the only artifacts on view, those re-presented by Gala Porras-Kim come from a local anthropology museum’s ethnographic collection. She exhibits for the first time those broken shards, loose feathers, and other sundries from the Fowler Museum’s collection of either dubious provenance or broken unpresentability.

And what about that which is left out, abandoned by the bright, brand-new now? Artist Fred Lonidier’s almost three-decade long public access television show Labor Link TV (1998–2011), included here on posters and a bank of TVs, covered labor politics and union rights. The workers seen here were the ones very clearly left behind. Los Angeles is still the largest manufacturing city in the country2 (my father worked in one of the union factories here for over 40 years), even if as is the case with Sterling Ruby’s eight large metal workbenches, each titled Table (2015), with a number from 1 through 9 (7 is not on view), leftover when he moved into his studio, this history’s been repurposed for its sculptural presence. (Whilst we’re on labor, I might add that no museum in Los Angeles, including the Hammer, is W.A.G.E. Certified.)3 With his mudbrick installation Tierra (2016)—made of bricks the artist made with his father and pieces of furniture—that fills a large swathe of the second-floor patio, Rafa Esparza marks a physical struggle of how difficult it is for migrants here to make a home. In Los Angeles, a city composed largely of castaway humans with some sunkissed dreams of prosperity, where do we put those things and people that don’t belong? Those humans easily abandoned by the cutting-edge commerce of high fashion and “trend forecasting”?

Kenzi Shiokava (born in 1938) actually was Marlon Brando’s gardener. His works, totemic assemblages of detritus and flora, find a place, as does the artist, in that flip-side of 1960s finish-fetish, made primarily by African American artists in Los Angeles. Composed of wood and found material, his various Totems tower with an almost animistic spiritual force (his works on view date from 1973 to 2007). An emigrant from Brazil of Japanese parentage, Shiokava has long been an artist-in-residence at the Watts Towers Art Center, teaching classes in Simon Rodia’s triumphantly makeshift architectural sculpture. Shiokava and his work are everything I love about Los Angeles. Drawn from a scatter of places but still literally homegrown, scrapped together here from castoffs with a spiritual force and odd play, fearlessly high and low, and somehow indirectly supported by a film industry it really has nothing to do with. That he gets his big debut at 78 and that he worked for so long without commercial or curatorial recognition is a state of affairs I’ll let you make your own judgments about, but his presence here feels really good.

However well-educated, Laida Lertxundi’s films look at Los Angeles without clearly trying to dictate the terms of what we’re seeing. Southern California here is seen meditatively, obliquely. Visions marked specifically by the filmmaker’s experiences as a woman, a human born in Spain after Franco, and a person from elsewhere who came to LA to study. Soundtracked by mixture of heartbeats, field recordings, experimental sound, and pop music (a musicality reflected throughout the exhibition, most clearly in the contributions of displayed experimental scores by veteran musician Wadada Leo Smith), her films feel just dreamy enough and real enough for me to lose myself in the pictures. Here I found some Los Angeles I recognized, a place I live, work, suffer, raise a child. A place of sordid romance and strange light, striking visions of natural beauty behind and between stucco apartments.

All of it, somehow, somewhere on film.

Jori Finkel, “‘Made in L.A.,’ at the Hammer, Excavates Hollywood’s Past,” The New York Times, June 19, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/20/arts/design/made-in-la-at-the-hammer-excavates-hollywoods-past.html?_r=0.

Eric Morath, “Where Are the Most U.S. Manufacturing Workers? Los Angeles,” The Wall Street Journal, June 15, 2015, http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2015/07/15/where-are-the-most-u-s-manufacturing-workers-los-angeles/.

http://www.wageforwork.com/certification/1/about-certification.