Irene ist Viele!1

An extensive 2004 study undertaken by the Swiss Federal Office of Statistics (BFS) found that, in one of the world’s wealthiest countries, of nearly fifteen billion annual work hours, eight billion went unpaid. Two-thirds of that free labor was performed by women, while women in the wage-labor sector were paid on average 18 percent less than men.2 The study shows that the “invisible hand of the market,” with its celebrated promise of economic equality, fails when it comes to social, cultural, and life-sustaining activities; furthermore, it appears that the “free market” has something against women. If, on top of this, the current form of capitalism is characterized by its extension of the logic of commodity production into the social realm (although, according to its classical self-conception, the capitalist economy actually claims to exclude the interpersonal realm), this means that not only wages and social services are reduced and cut, but above all that the reproductive reserves are plundered.3 According to many contemporary theorists, what was considered in the Fordist system to be external to the concerns of the economy—communication, personalized services, social relationships, lifestyle, subjectivity—today establishes the conditions for the generation of wealth. Social and cultural competences and processes—the most varied forms of knowledge production and dissemination—are central to what Antonella Corsani calls “cognitive” capitalism.4

Thus the current debate surrounding precarity in Europe, as a neoliberal condition and a comprehensive mode of subjectivity, doesn’t stop where wage labor or social-state welfare ends, but rather seeks out perspectives that help us to think beyond the reductive logic of the current conception of work, and beyond the nation-state as well. This also means being able to consider the material, social, and symbolic conditions necessary for life as interconnected entities that can overcome the traditional dichotomies of public/private and production/reproduction to set new standards for living life with all its facets and contingencies.5

But how does a life look when it doesn’t define itself in relation to the status of wage labor, but rather through the desire to freely decide one’s own conditions for living and working, effectively comprising a demand for a flexible labor market? What does it mean for our work and life when the social, the cultural, and the economic cease to be clearly distinguishable categories and instead condition and permeate each other? Beyond this, what does it mean when people come to terms with these new forms of work as isolated individuals? What can forms of collectivity look like? And what does it mean when there is not only no consideration of the redistribution of wealth in the precarity debate, but also no consideration of a good life for all? How do we expect to work politically to develop overall social conditions when the theoretical premises of their transformation remain to a large degree unexplained?

In this text I will pursue these questions in relation to a 1978 film by Helke Sander titled Redupers. Die allseitig reduzierte Persönlichkeit (The All-Around Reduced Personality: Outtakes). At the end of the 1970s, this film already tried to consider the immanence of liberation ideals and self-determination in capitalist societies. In a way, it represents a possible historical starting point for the current debate over forces of production, precarity, and critical potential by illustrating that, even in the upheaval of changes in the capitalist as well as gender order that took place in the transition from Fordism to post-Fordism, many networked and self-organizing production conditions (what today would be considered the source of “immaterial work”) were already present—and were being analyzed by feminists.

In the Magnifying Glass of Non-Work

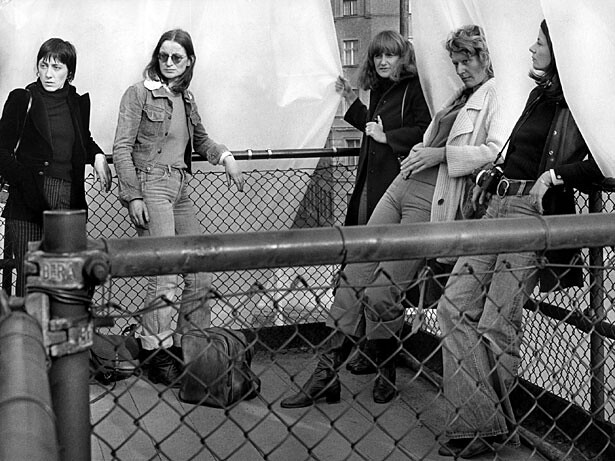

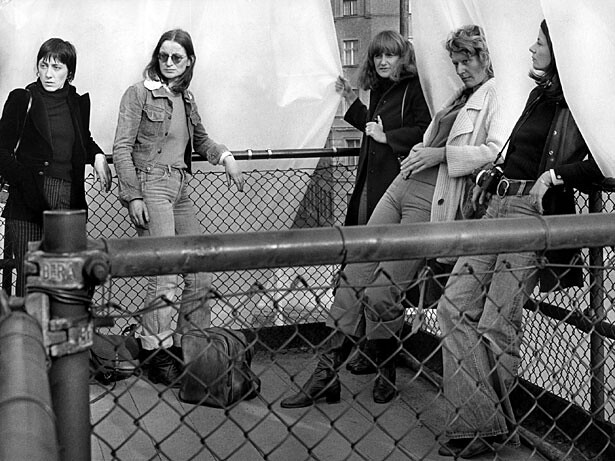

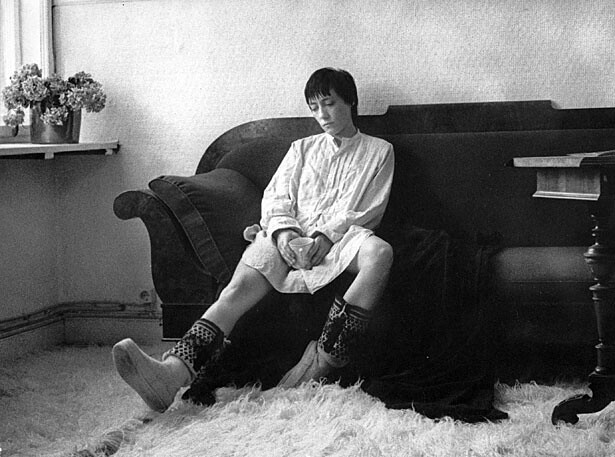

Redupers is set in the still-divided Berlin of the 1970s. The film begins with, and is continuously interrupted by, pans of Berlin’s graffiti and slogan-covered facades, reminding us of the social struggles of 1968 or the binary socialist and capitalist power blocs. Against this backdrop of the city’s ever-present division and the fading memory of the 1968 revolution, the film tells of the everyday life and work of a young press photographer and single mother who works with a feminist collective in addition to her regular job. Director Helke Sander plays the main character in Redupers herself: a photographer who “produces,” develops, prints, and sells images as a freelancer for a Berlin newspaper, lives in a shared apartment with her daughter and a friend, and is in a relationship with a man who is not the father of her child. She works with a feminist producers’ collective on a countercultural project in the public sphere and, as part of a Berlin art collective, on an exhibition directed against the dominant capitalist image of West Berlin. The whole construction of the film doesn’t only destabilize prevailing notions around the separation of public and private realms, or the classical division of labor between director, author, and actor, but can also be read as a document of a form of self-representation that destabilizes parliamentary democracies’ claims that the will and interest of “the people” or the subaltern must be represented by institutions and the media in order to be valid.6

From the beginning, this can be understood as political positioning on the filmmaker’s part. Helke Sander is also a central figure of the so-called First Women’s Movement. At the 1968 conference of the Socialist German Student Union (SDS) in Berlin she delivered the speech on behalf of the Action Committee on the Liberation of Women, an event that ended with the famous tomato being thrown at her comrades. In this speech, Sander demanded that the functionalist precept rooted in political economy, according to which capitalism must determine all social conditions, be set aside. Power relations in the private sphere, which affect women above all, cannot be accommodated in this perspective, but are instead denied and dismissed as a secondary contradiction. The political project shared by leftist men and women could not, according to Sander, be successful as long as only “exceptional women” were recognized by the merit system of the leftist intelligentsia. The question of the political project lies, according to Sander, in the method by which it is practiced. What was necessary was a political practice that recognizes the private realm, the body, gender relations, and the realm of reproduction as a political sphere.

The politicization of the private is a central motif of the social movements of the 1970s and is found throughout the film. Redupers no longer places this critique of the normative role of the housewife at the center. Instead, the filmmaker uses the politicized perspective on the private to examine the most varied activities and constraints, drawing connections to the social, economic, and cultural fields, and the power relationships at work between them. The question of the mother’s care for the daughter and their relationship plays an important role, although social conditions in the film are indicated primarily by the ever-changing demands imposed upon the overworked protagonist, whose career as a press photographer requires her to be on location at irregular times, and with little notice. Beyond the unresolved question of care, the film remains attentive to all the invisible operations that comprise work within the culture as well—those not related directly to the sale of photographs: shopping for film, working in the darkroom, developing the film and printing the photos, drying and pressing the prints as well as retouching the images; but also: negotiating assignments, remaining informed about social events, maintaining contact with the persons photographed, which also goes beyond a working relationship, as well as submitting invoices and collecting honoraria, preparing tax returns, etc. The cash-value of the compensation that the photographer Edda receives in Sander’s film for her photos, with which she defrays all expenses for both her daughter’s and her own subsistence, and for all her other projects, can never make up for all of this activity. Even just with regard to the production of the photos, it doesn’t even amount to a decent hourly wage. The sale of photographs as a finished product thus contains contradictions very similar to those of selling one’s own labor to capital. As the photograph is only a snapshot of an instant in a live event, frozen and commodified, so also is the work performed for the production of the image not contained in the price. In a similar way, life-sustaining, social, and communicative activities are also frozen in the concept of labor, consumed by capital like a commodity.7

This understanding has a historical side: that of the discovery of work as a source of property and wealth, from John Locke and Adam Smith to Marx’s Systems of Work and the political economy as science. In the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries thinkers of all stripes apparently agreed that “work” alone represents human beings’ most productive means of shaping the world and forming values. Even when Karl Marx, in his critique of the Gotha program, strongly criticized the claim that work is the source of all wealth (he asserted that nature is also a source of wealth and that the fetish for work is an expression of bourgeois ideology), during the period of industrialization through the radical re-evaluation of the overall social status of work, there were a striking number of other activities that assumed that they could form world and value as well. The most obvious reason why the theorists of the nineteenth century weren’t aware of the radical limitations of this concept of work is rooted, according to Hannah Arendt, in the fact that they only attributed work to the production of sellable goods.8

Throughout industrialization, the concept of work came to be understood according to its capacity for maximizing profit and producing value. But this also meant that such a concept can neither encompass “work” in the life-sustaining sense nor productivity in any non-capitalist sense. Karl Marx conceived of work in much broader terms than those of the male factory worker. He also considered “making the audience laugh” (cultural work / entertainment industry) to be work, and protested against those of the workers’ movement who only understood traditional industrial labor as work. Sweat and muscle power, real manpower, and the machine hall were apparently easier to politicize than the comics, entertainers, or women—for whom the “other” industry of unpaid caretaking, childrearing, shopping, and housework were intended—on the basis of their so-called feminine characteristics. The circumstances of their exploitation were hidden, but no less brutal in their effects. In contrast to the entertainment industry, which was quite small at the time, this second industry concerned almost the entire “other half” of society. Alongside the sticky psycho-social dependency of the genders, the dichotomy formed by the woman’s dependency upon the money of the man would determine the entire symbolic order of industrial capitalism.

But reducing work to production also went beyond this to lock the theoretical approaches inside the factory, so to speak. It did not take long for the critique of capitalism to consider the gendering of paid and unpaid labor alongside its role in producing capital as well.9

Living a life that unfolds in opposing directions, the main character in Helke Sander’s film points to the imprecision of this discourse. While her “free time” is spent working with her female friends on an art project—as she says “one interesting project or another is always blowing into my house”—her days remain filled with different activities characterized by usefulness and/or idealism, both informal and normally undocumented. While her work as a press photographer secures her income and is what she describes as her actual career, the other activity—working on a cultural project—fulfills her desire for a collective, feminist practice, for change and cultural and political empowerment. At the same time, both are work, as is caring for her daughter. But in these apparently self-determined conditions, as the film shows, the unpaid care work remains not only the responsibility of women, but also invisible to the commodity forms of knowledge and cultural production. Self-organized work is also split into remunerative work offering financial support and artistic, self-actualizing, collective work that brings in cultural and social capital. And yet the care work at home is taken into account by neither occupation. While her cultural-political work is coupled with the actualization of meaningful individual and collective desires, the care work must somehow be organized around it. Her work with a group of women on a project to design a counter-image to the dominant one of a divided and cut-off Berlin is indeed more meaningful than freezing into photographs “events which are of publishable value for the newspaper.” The women’s project for the Berlin art association doesn’t only reflect the de-valuation of care work to that of a burdensome activity, but also points to the different levels of their own participation in the same dominant condition, as well as to their individual desires for public recognition. The sexist logic of society and the desire to change it thus come dangerously close to one another. In this way, the film’s politicization of the private dissolves into new concepts of occupation and career, but while it finds its place in the self-actualization of “more meaningful” work, it no longer locates this change in the social conditions themselves.10

All-Around Reduced Views

Sander’s film focuses on this absence in its descriptions of all the daily activities we perform in private and public space. For more than thirty years, feminist economists have examined work relationships and conditions from the perspective of non-work, calling our attention to the fact that the field of political economy (which is about two hundred and fifty years old) has until now only addressed commodity production and not the question of how to bring about sociality. On the one hand, this is because the field developed alongside mechanization and industrialization and was in a position to theorize these new production systems and capital relations, but also because a specific ruling form of subjectivity became central to the development of Western capitalist society: the homo economicus, the subject of this economy, with white skin and masculine gender, who follows his own interests and whose self-interest is also believed to serve the interests of all others. According to Elisabeth Stiefel, an economist from Cologne, the homo economicus represents not only the tasks of the public economic sphere, but also those of the head of household, while the interior of the household is terra incognita for economic theory. The social and the cultural thus remain fundamentally exterior to the understanding of the economical. As classical economic theory assumed care work to be self-evident—and therefore performed for free—women had to take on unpaid “extra-economical” activities for “cultural” reasons, and this gendering of paid and unpaid work, which even today finds a significant disparity in the pay of men and women, has not hurt capital in the slightest in two hundred years.

The separation of social, cultural, and economic discourses from those of production and reproduction has solidified a theoretical reductionism which has made it difficult to discern where and how to economically position the analysis and critique of post-Fordist work and life conditions, especially because it is precisely those extra-economic conditions that have become central for the production of added value. How can we begin to bring these into a discussion about the re-distribution of wealth, when above all wage labor can no longer be guaranteed? How can we demand payment for something that is not yet considered in an economic sense work? And do we even want to recognize and monetize non-work as “work” at all, thereby economizing all aspects of life?

It becomes even more complicated to address these questions when they extend, together with gender duality and its location in the (neo-)classical work imperative, into the desire economy of a “good life.”

Sander’s film also speaks to this. The figure of the photographer also plays a double role in the film: as both occupation and as a self-actualization project. The photographer historically represents an exception to the gendered division of labor, as it was one of the first occupations to witness an altered discourse of visuality brought about by new technologies, and this opened possibilities for self-sufficiency and financial independence to not just men. The female photographer thus functions as a kind of role model for women, since the possession of her own money in this “creative occupation” could be associated with liberation from the heterosexual regime. Thus it was not unusual for these self-sufficient women to live with other women and not be married to men. The techno-emancipative role model in Sander’s film witnesses this historical narrative at the end of the 1970s, in a new situation between diligent self-organization and a relatively bureaucratic information and culture industry, in which the underpayment of freelance workers has become the rule. At the same time, Sander’s figure of the photographer shows who has access to the representation of the world and who selects, determines, and utilizes it.

In a central scene, in which the photographer Edda calls the newspaper editors seeking payment due to her, and her just-awoken friend finds the bathroom full of developed film, a conflict emerges: the good, non-heteronormative life together—being self-sufficient and earning money from home—and being dependent on editors. The economic reality of self-employment that was previously understood as emancipatory eats more and more into Edda’s personal relationships. The emancipatory struggle that had the good life as its objective now reappears in the unsatisfied longing for change and the struggle to survive.

Against this backdrop, the film reflects the fact that the desire for feminist, occupational, and cultural-political self-sufficiency—the personal responsibility of earning money and working in the counterculture—have inverted to become their opposites. They are not only unable to resolve the social contradictions that they set out to overcome, but become mired in them instead. The protagonist’s various motivations for wanting to become self-sufficient (by becoming a press photographer and an artist) connect completely in the film for the first time when the protagonist enters a new relationship with herself by going on a visit to the editorial floor of the magazine Stern to promote her feminist art project. In the scene, the photographer Edda puts on makeup and perfume, and, thinking as she walks down the hall to the journalist’s office, “if I really wanted to represent what is right in my job as press photographer, I would have to be at home here (in the halls of Stern).” In this situation, it is her cultural self speaking, but not her career self, and certainly not her activist self. The interplay of her various repertoires—the fragmentation of her person—is especially clear here. This scene suggests how, by working by herself and on projects outside of her career, Edda finds options for a “better position” on the horizon. The mix of positions and activities also becomes a “portfolio”: what she has done without pay and possibly with a higher degree of political investment accumulates social or cultural capital which is usable in other markets for a better position or a career in art. This points to a practice that has transformed into a dominant work-related demand today, in which unpaid internships and other indignities are part of a “normal career.”

In Switzerland today, job seekers show their unpaid work in their résumés, on the one hand to signal their “willingness to work,” but also to show their flexibility and versatility in the tightening job market. The feminist demand for the visibility of unpaid work seems realized here, but at the same time, the documentation of the informal serves only the efficiency logic of existing capitalist conditions by indicating a capability and readiness for wage labor.

The Stern editor was unresponsive to the film’s protagonist. For him, she is “only” a figure of the women’s movement—a feminist and a political activist. Not only is she denied the role of a cultural producer who can represent political conditions, but so is she denied any possible success as well. Here Sander illustrates what usually remains acknowledged in current theories on the emergent productivity of individual desires within neoliberalism: that pay for work performed in vastly different markets does not equal the sum of the parts. Viewed from today’s perspective, the film not only caricatures government-funded start-ups and the plans of the Hartz commission, but also corrects the idea that the celebrated figure of the “entrepreneurial self” is not gendered or part of a hierarchy. The reflective, connection-forming, and knowledge-producing form of work sketched out here also points to a change in society through which new claims to activity, collectivity, and property can be negotiated.

The protagonist is not only photographer, feminist activist, and theorist, that is, cultural producer, but also a product of emancipatory demands and capitalist impositions, a subject who has pulled away from wage labor and its regulatory apparatus in the factory or in the office, as the Autonomia Operaia called for. At the same time, she is a Reduper (an all-around REDUced PERson)—a figure who cannot be located biographically, and instead requires a new form of subjectivity to be realized in the contradictions of capitalist socialization. In this way, Redupers marks the post-Fordist convergence of work relationships, subjectivity, desires, and political demands that has consequently brought about a multitude of all-around reduced personalities.

Creating Probabilities

Three decades after Redupers, the call for self-determination and social participation is no longer only an emancipatory demand, but increasingly also a social obligation. In the new conditions of governance, subjects are pushed towards maturity, autonomy, and personal responsibility. They seem to willingly subordinate themselves to the dispositions of power—they are “obliged to be free” (Nikolas Rose). Forms of discipline that were used in the time of mechanization and industrialization have been extended in post-Fordist societies into new forms of control. Contemporary forms of organization discipline subjects and their bodies less through “guilt and punishment,” and more by aiming at internalizing productivity goals. This produces a new relationship of the subject to itself—friendliness towards customers, working with the team, increasing one’s own motivation, self-organizing work routines, managing time efficiently, and being personally responsible for both the company’s and one’s own actions are not only demands being made on the work subject, but increasingly also on the unemployed. According to Michel Foucault, this new concept of governing “is not a way to force people to do what the governor wants; it is always a versatile equilibrium, with complementarity and conflicts between techniques which assure coercion and processes through which the self is constructed or modified by himself.”11 One’s behavior in a more or less open field of possibility therefore determines the path of success. Exertion of power consists, in this sense and according to Foucault, in the “creation of probability.”12

Accordingly, it is not a disciplinary regime that guides the subject’s actions, but rather a set of governing practices that mobilize and encourage rather than “survey and punish.” The new subjects of work should apparently be as contingent and flexible as the “markets.” A work subject who is able to find a productive relationship between work time and life time is “supported and challenged,” and within this relationship private activities are also geared toward economic use value. The entrepreneur of one’s own labor13 should also be the artist of his/her own life. The hope that these paradoxical demands could become dominant labor market politics is likely due to the fact that under such conditions, workers can always feel “liberated” from constraints, as Helke Sander’s film was already able to show in 1978. It must be worked out, therefore, how the transition from liberation programs to job specifications takes place, and whether and for whom they are effective. Three decades after Redupers, we need to ask how the relationship between work and non-work can be politicized when their coupling has already become hegemonic in its representation.

Although the economic field, in a double sense, mobilizes and controls the social realm, the paradigms of capitalist production remain the same. They do not inform the “resources” of our social lives themselves, even (and especially) if cognitive capitalism has parasitically positioned itself at the side of reproduction. Acceleration and maximizing profit continue to be advanced as the necessary logic of the market. Life itself is subsumed under the rules of efficiency and optimization that were first encountered under the regime of automated industrial work in order to synchronize the body with machines.14 Today, it is our cognitive capabilities that we are expected to optimize and our self-relation (to our work) that we are expected to correct in the interest of lifelong learning.15

Beyond this, the film Redupers shows that the anchoring of neoliberal ideology in the subject cannot only be considered to be a product of post-Fordist production or the information economy. Rather, the film points to arguments made by Éve Chiapello and Luc Boltanski, who in their book The New Spirit of Capitalism undertake a sociology of the critique of capitalism since 1968.16 They examine the “social critique” that became engaged on the political level for the redistribution of wealth and for equal rights as well as the “artistic critique” that emerged from the artistic and intellectual avant-gardes such as the Situationists and various social movements of the postwar era. With demands for autonomy, authenticity, and creativity, but also through artistic practices beyond the classical concept of the work of art, these critiques attacked the use of the social as commodity form, discipline in the factory, bureaucratic inertia, and hierarchical power relations in the industrial societies. Boltanski and Chiapello then argue that it is precisely capitalism’s adaptation to these “cultural critiques” that increasingly corroded the politicization of life and the social critique of property relations, thus paving the way for neoliberalism.

According to Yann Moulier Boutang, the classical conception of economic value and measurement changes in cognitive capitalism, since the growing use and exchange of knowledge in post-Fordist production extends far beyond its economic utilization as commodity.17 The viral dynamics of new distribution technologies such as the internet renders information and knowledge far less accessible to supervisory bodies, as Sander’s film also suggests. In the transformation of the old economy, these new possibilities also point to a new field of struggle—such as the conflicts and arguments over intellectual property and the so-called commons.

After viewing Redupers against a backdrop of contemporary economic analysis, it seems insufficient to simply point out the limits in the study of political economy or to show that capitalism has incorporated certain concepts of life for its own advancement. Rather, we must also ask whether and how a critique of capitalism can make allowances for the alliance of work and life within the subject’s own domain—its biopolitical preparations and desires—without getting mired in merely describing them as another advanced form of exploitation.

“Irene ist Viele” refers to Helke Sander’s film Eine Prämie für Irene [A Bonus for Irene] (1971), in which the voiceover says “Irene ist Viele” (Irene is many). In the film, the figure of Irene stands for the many factory workers who are single mothers. Eine Prämie für Irene was one of the first films in Germany to suggest the interrelations between the public and the private spheres. “Irene ist Viele” was also the title of a film program I curated together with art historian Rachel Mader in the Shedhalle Zürich in 1996, in which films by feminist filmmakers from Germany and Switzerland were reviewed and reevaluated together with the filmmakers. Helke Sander was part of this important event that also tried to bridge older and younger generations.

According to a 2004 study by the Swiss Federal Office of Statistics (BFS), two-thirds of all unpaid work is performed by women. This corresponds to an equivalent of 172 billion Swiss Francs or 70 percent of the gross domestic product. In the future, unpaid work is to be economically evaluated on a regular basis. Although this calculation, based upon an estimation of market costs, is necessarily inexact, this sum corresponds to nearly the entire yearly wages of employed workers in Switzerland.

Mascha Madörin, “Der kleine Unterschied in hunderttausend Franken,” Widerspruch 31 (1996): 127–142. See also Pauline Boudry, Brigitta Kuster, and Renate Lorenz, eds., Reproduktionskonten fälschen! Heterosexualität, Arbeit und Zuhause (Berlin: b_books, 1999).

Contemporary production models are characterized by their transformation of workers’ learned skills not used in the workplace into a productive force. The post-operaistic theorists in France and Italy have shown that all immaterial and affective work gains significance in post-Fordist production. With investigations into the reorganization of the automotive and textile industries in northern Italy and the image industries in Île de France, these theorists of “immaterial work” have also shown that communication and subjectivity are not only components of postindustrial, informalized, and informal production, but also themselves become an applied process in the industrial sector and the scene of new struggles. See also Maurizio Lazzarato, “Immaterielle Arbeit. Gesellschaftliche Tätigkeit unter den Bedingungen des Postfordismus,” in Umherschweifende Produzenten. Immaterielle Arbeit und Subversion, ed. Thomas Atzert (Berlin : ID-Archiv, 1998), 39–52, and Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000).

Affective and communicative interaction and the creation of sociality and subjectivity never become economically valuable, but are rather always valuable for life itself. The social doesn’t stop when one leaves the workplace, whether this be at home or in the office, and thus it can also never fully be absorbed by capital, since affects cannot be exclusively industrially organized (even if this is attempted in the image and film industry). If immaterial work, interaction, and communication can become a resource for accumulation, or even become a commodity, then this means that a vital aspect of the work force can no longer be clearly determined through measurements such as working hours, price comparisons, or possessions. The subjectivity of the workers doesn’t end in an imaginary factory, but has rather a further effect on different social processes which are not only marked by their economic value, although they can, in the reverse argument, generate it. This also means asking how we ourselves reproduce or bring about the conditions that we criticize. See the project Atelier Europa, which I developed together with Pauline Boudry, Brigitta Kuster, Isabell Lorey, Angela McRobbie, and Katja Reichard, in which we carried out a “militant investigation” with cultural producers; see also Be Creative! The Creative Imperative, which I organized with students and theorists for the Museum of Design, Zurich, →.

The film is the expression of these demands for (self-)representation which emerged from the struggles against the exercise of control over subjectivity and are and were central to both the social and global emancipation movements.

It was Marx’s achievement to have analyzed the abstraction process in which work is transformed in the capitalist accumulation into labor (Arbeitskraft, lit. work-force): into a seemingly measurable size. Capital doesn’t buy all the necessary and living work, nor even the social, cultural, and spatial conditions to afford them, but rather a time-energy-money equivalence, in which life-sustaining activities are unnamed but apparently included. Labor was therefore also bought in the time of industrialization as a pre-produced commodity, in which the actual production relations which produce the commodity labor remain hidden. Thus capital in the time of industrialization had command over care work, communication, and lifestyle.

Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958).

This missing perspective refers to the “becoming-subject” of factory work as a masculine muscular body with white skin, which would have to be analyzed in order to make a complete critique of the discipline and the making-effective of the body and its exploitation—up through existential destruction in the time of industrialization.

Today, this means that migrants are underpaid to perform the remaining non-prestige care work so that the men and women wrapped up in their wage work or prestige work can carry out their paid or unpaid status work. Care work, which under traditional gender regimes was coupled to the subject position of the housewife, is now bought as a service on the market, or pushed upon those who can’t buy it. After finishing cleaning and care work, the servant cannot afford a servant of his/her own who would perform this work in their own home.

Michel Foucault, “About the Beginning of the Hermeneutics of the Self: Two Lectures at Dartmouth,” in Political Theory, Vol. 21, No. 2 (May, 1993): 198–227, 203f. Foucault’s conception of governing as “determining the conduct of individuals” focuses on how “the contact point where the individuals are driven by others is tied to the way they conduct themselves.” Foucault’s argument is that, by means of these so-called “technologies of the self,” a much more profound integration of the individual into power takes place, without which the functional modes of modern Western society are difficult to imagine.

Originally “Schaffung der Wahrscheinlichkeit,” in Michel Foucault, “Das Subjekt und die Macht,” Jenseits von Strukturalismus und Hermeneutik, eds. Hubert L. Dreyfus and Paul Rabinow (Frankfurt am Main: Athenäum, 1987), 255.

See G. Günter Voß and Hans J. Pongratz, “Der Arbeitskraftunternehmer. Eine neue Grundform der Ware Arbeitskraft?,” Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Soz-ialpsychologie 50, no. 1 (1998): 131–158.

The effects of this acceleration and its attendant standardization are especially clear in the service sector, the care economy, and the entire health and social systems that come under the constraints of quality management and increased efficiency as well as austere fiscal policy. The same is also true according to the Bologna negotiations for the education system of the entire European Union.

See a collection of texts devoted to this question, Norm der Abweichung, ed. Marion von Osten (Vienna: Springer, 2003).

Luc Boltanski and Ève Chiapello, Der neue Geist des Kapitalismus (Konstanz: UVK Universitätsverlag Konstanz, 2003).

See Yann Moulier Boutang, “Neue Grenzziehungen in der Politischen Ökonomie,” in Norm der Abweichung, 251–280. This crisis becomes clear, for example, in the suggested VW pay scale introduced in 2003 by Peter Hartz, member of the Volkswagen board and the personification of labor market reform. Here Hartz establishes the so-called “job family,” in which the different levels of a production process should now be viewed and paid as an “organic whole” of various productive forces. From a designer to a mechanic to a painter, a job family is a team brought into a dependence that is “productive” for the individual but nonetheless negative. We also see the crisis of the definition of necessary work in the discussion over a guaranteed income—in which the production of life as necessary prerequisite for a work life or an unemployed existence are considered.

Category

Subject

Translated from the German by Jennifer Cameron