Tradition! Tradition! Tradition!

—“Tradition,” Fiddler on the Roof (1964)

On television, people marvel at the change. Marriage, that privileged heterosexual union, that millennia-long social institution said to be sanctified by the Christian God and his analogues, now seems to be going the way of other revered cultural traditions like slavery and human sacrifice; its terms are no longer so clearly defined. In the spring of 2013, eleven full-fledged nation-states permit “same-sex marriage”; predictably, most are in Europe, though Argentina, South Africa, and Canada are on the list. In some countries, gay marriage is working its way through the system, and in some countries, the map is fractured, with some jurisdictions recognizing the legal coupling of two men or two women, and others not. Such is the case in my country, the United States of America, a prominent nation-state with a lot of attitude. Here, the highest judicial instrument, the Supreme Court, reviewed in the week prior to this writing two cases that test the legal definition of marriage. As it’s a court that in its current composition precariously balances an extreme right wing against a moderate social democratic wing, it’s somewhat surprising to many, and disturbingly telling to others, that these cases appear to be heading toward an expansion of gay civil rights.

As many readers will know, one of the cases under consideration challenges a law passed by the US Congress in 1996 and signed by then-president Clinton, ominously titled “The Defense of Marriage Act,” which anticipated this current moment by preemptively protecting the federal government from invasive gay marriages granted by states, which are the conventional custodians of marriage rights. The other case, the “Prop 8” case, covers a complex turn of events in California where this writer was among the 36,000 people (more frequently referred to as 18,000 couples) gay-married in 2008 inside of a narrow legal window between a court’s spring decision and an autumnal voter referendum. My semi-legal spouse and I were in Washington, DC on the day this case was argued and we visited the steps of the court, where activists, media, and onlookers gathered.

Most of those assembled were supporters, though detractors were there as well, from the normative mom + dad types, to the extremely paranoid and inflammatory, dressed as Jesus Christ, holding big books, bearing gigantic signs conflating sodomy, AIDS, a degraded Uncle Sam, and men kissing—a mélange of gay-hating and straight-marriage defending. Two nice women who work at the Library of Congress approached us on their lunch break, and though they were aware of the general contours of the discussion, they asked us to explain the ins and outs of the cases, which are both rather baroque.

The entire episode reminded me of two points I wish to raise here: the first is that these legal problems resemble less the solid march of normative hegemony causing my radical queer friends and allies so much apprehension, and more a messy hodgepodge of confusion around the arbitrary constructions of citizenship, statehood, and human rights that have shaped participation in modern representative states since the European Enlightenment. The second issue is that the most prominent critics of gay marriage are many of the most reactionary forces out there, and though I agree with much (but not all) of the queer critique of marriage, I would ask my queer sisters, brothers, and others: Whose coalition do you really want to join?

There is nothing fair in this world

There is nothing safe in this world

There is nothing sure in this world

There is nothing pure in this world

There must be something left in this world

Start again!

—“White Wedding,” from Billy Idol’s album Billy Idol (1982)

In May 2012, I participated in a symposium organized by Carlos Motta and Raegan Truax as a part of “We Who Feel Differently,” Motta’s exhibition at the New Museum. There, within a broad range of presentations about sexuality, difference, policy, and media, Motta and others expressed some of the views constituting what we might call the queer critique of marriage. This critique has three basic parts: one principled, one practical, one strategic. The first is that marriage itself is a conservative institution, half of the public-private partnership that constitutes capitalist societies and their punishing, exploitative, compulsory regimes, and it should be abolished rather than expanded. The second is that the political agenda of queer activism, which originated in the heroic efforts of people fighting for their lives, has been hijacked by privileged cisgender white gays and lesbians who have diverted all political resources toward marriage and away from the urgent issues still facing vulnerable people, which include legal housing and employment discrimination, access to public resources, problems of criminal justice, and a culture of violence. The third is that queerness is a marginal, deviant, oppositional, countercultural, radical space that should be preserved, not co-opted. Points one and two are right on; the third deserves some unpacking.

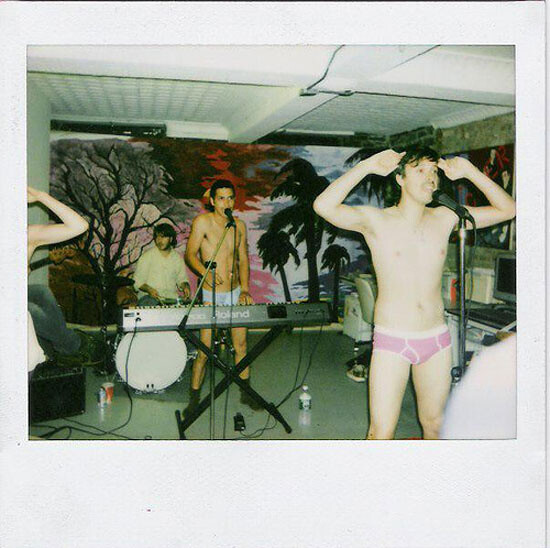

Asked to conclude a day of panels with a short performance, I decided to push back a little through what I’ve been calling a discursive piano bar act, weaving together the American songbook with pop while singing at the piano, and filling the intertextual gaps with some commentary. A genre that mobilizes ambivalent potential, the gay piano bar set brings musical-theatrical materials together, mining Broadway and popular archives that often connect to historically closeted producers, and songs that were famously executed by performers around whom queer allegiances and identifications have created extra-textual meanings. The genre may be anachronistic in an era of out positivity, when the careful nuances of the closet are no longer required, and theatrical subterfuge, codes, and ironic double-meanings no longer function as the only ways to speak about sexuality. But brought out of the closet, these expressive strategies can say even more, and more explicitly, while offering access to a historical practice of gay critical ambivalence.

Ambivalence has been discussed of late as a useful model for managing a matrix of positions, rather than as simply an abdication of positionality. The term helps us think beyond binary structures, and about multiple ways of being that can and must be negotiated and renegotiated provisionally, all the time. In relation to heteronormativity, queerness is already an ambivalent position, and one made of differences.1 The queer subject cannot be constituted in any ontological sense. Imagine the queer people you know and try to arrange them into a unity and you may find, as I do, that none exists. Queer is everything that’s not heteronormative. “Not this” or “not that” is no way to define being, particularly in the Western philosophical tradition that brought us the idea of the individual autonomous subject in the first place.

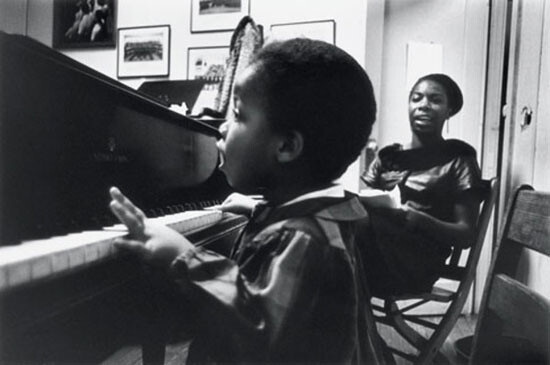

In other writing, drawing on histories of African American cultural production, looking at expressive forms that also derive from a prohibited subject position, I have thought about the experience of subjectivity as a more dynamic opportunity for action than the mode of agency attributed to subjecthood. “The subject”—of law, of grammar, of human rights, the consumer, the citizen—is a universalized yet restrictive formation that is fulfilled by objects. In the black tradition, objecthood has been a more pervasive experience than subjecthood. On the other hand, everyone has access to subjectivity and some ability to express its terms. Remembering that these histories are different, but considering the ways that civil rights struggles attempt to gain access to agency, and following contours of the public discussion, it’s instructive to look at what blackness and queerness share. In both, one can appreciate the ways that daring people have taken terms shaped around exclusion and produced from them multiple positions from which to act. These positions are mobilized not by a universal notion of being, but from the bottom up, built from experience.

Same-sex marriage is experienced and expressed differently depending on one’s position: hedge fund guys, working-class moms, weirdos in love, gay middle managers, those in practical need of health insurance, immigration status, and so forth. With all of these different experiences in mind, it becomes necessary to complicate the antagonism between normative/radical, center/margin, culture/counterculture. In each of those formations, the second term is instigated by the prior term. The prior term is in fact structured around, mobilized by, dependent on its supposed opposite. To be named, heteronormativity must exist in relation to a defined abnormal object, while the subjective experience of queerness is rather flexible and less easily defined. Queerness can mean being more than one thing at a time, can be ambivalent, and is productively understood as a collection of simultaneous differences. In this sense, valuing the ambivalence of subjectivity is a way to imagine beyond rational binary formations that always use a subject to put an object in its place. All of this is to reiterate that the radical queer critique of same-sex marriage misses some of the point of what’s valuable in breaking oppressive dominant terms into little queer pieces. This breaking-up is also the aim of my discursive piano bar act.

Now we begin

Now we start

Only death will part us now

—“One Hand, One Heart,” West Side Story (1961)

Many people who know my partner Alex Segade and I have heard the story of our meeting. It’s 1991 and we’ve just started college, having moved away from our families for the first time only a month before. It’s National Coming Out Day, a new invention, and we both singly attended an event earlier on a campus lawn. Now, later at night, I’m alone in my dorm room watching my VHS copy of West Side Story for the millionth time. It’s raining and I’m feeling late-teenaged melancholy. I’ve “come out,” but no one really cares. In my recent past I’ve had one sex partner and a distant gay friend on the telephone, but no real boyfriends; my gayness was mostly expressed up until this point in the wearing of tight cut-off jean shorts. It’s the final scene where Maria is waving the gun around over Tony’s dead body as everyone watches dejectedly; “Shoot me too, Chino!” she exclaims in her unfortunate accent. I’m crying, of course. In comes my roommate. He’s into rock bands that will blow up a few months later and change popular music for the rest of the ‘90s, but he was into them first. He’s not into West Side Story. With him are a couple of other cool types: a smart-looking mod-ish girl and a punky gay guy with a shaved head and a pierced nose. He knows West Side Story quite well. We hit it off immediately, talk all night, and never really stop talking.

Some time later we had cutely awkward sex in another dorm room while one of us was coming down from LSD. We moved in together with other gay guys the following year, moved in together as a couple the year after, and after years of less formal creative collaboration, we cofounded My Barbarian in 2000, first a band and then an art performance group that is still very active. Recently, we both had the flu and watched West Side Story together in HD, which looked really weird and amazing, and we both cried at the end. Having invented a sturdy relationship out of our own evolving terms, marriage never occurred to us until the political Right started warning against it and passing laws prohibiting it. In 2008, seventeen years after that first dorm room meeting when I myself was seventeen, marriage became a legal possibility in the great state of California.

Back at Motta’s 2012 symposium, I broke down Laura Nyro’s Wedding Bell Blues and sang, “Radical queers, I love you so, I always will.” I offered some of my commentary while the music played: “Some of these folks just don’t like marriage. Just not their preferred agenda item. Too bourgie for them. May as well join the army. Fly a predator drone. Guess they’re not trying to get on anyone’s health insurance.” In my own defense of marriage act, which was grounded in my subjective experience of having married someone specific, this last point is one I want to reiterate, and is perhaps the more practically important of the three defenses I am going to make here. I don’t know where all of those queers who are opposed to same-sex marriage get their medical coverage. I imagine many don’t have any, while others have decent jobs or personal wealth that provide it. Others live in nation-states that give everyone health care and perhaps can’t relate to the desperation of this system. In our current household situation, one of us has a job that provides benefits while the other does not. This arrangement has flipped back and forth over the years, but no matter which of us has access to health care, we are now able to share that access. We weren’t always. Why would we reject an apparatus that allows us, at a cost of course, to share access? I’m picturing a scene in Bertolt Brecht’s play The Mother where it’s made clear that it is better to strike and starve than accept the exploitative terms of class oppressors. That may be true on some ideological plane of existence. Given the outcomes of communist revolutions so far, I’m willing to take the impure chance that it’s better to have health insurance in the USA than not, even when that access is unfortunately denied to so many others. This does not cancel out better goals, like universal health care, but it allows many of us to live long enough to work toward such better outcomes. My partner and I are child-free artists, relatively healthy, raised in the middle class, but still, this access seems like a dire need. As I consider those who I know are more vulnerable than us, I would not reject for them the possibility of an accident of rights-construction providing them with the ability to care for their bodies.

If I am dancing, then shoot my down

If I am wooing, get him out of town

For I’m getting married in the morning

Ding, dong, the bells are gonna chime

Feather and tar me

Call out the army

But get me to the city hall

Get me to the country clerk

God damn, get me to the church on time

—Adapted from “Get Me to the Church on Time,” My Fair Lady (1956)

The first queer couple I knew who got married were a trans-woman and trans-man whose official state documents denied their gender identities but depicted them as an opposite-sex couple, allowing them to marry. This arrangement worked for them, particularly when one of the two tragically passed away and the other, her legally recognized spouse, was empowered to tend to various details. These practical matters are no small thing in the real lives of real people. With this kind of circumstance in mind, but also with a interest in confronting the state as documented same-sex-ers, and knowing our rights would soon be taken away again by the popular vote, Alex and I went through the process of getting married. First we had to get a license from the East LA Country Clerk’s Office. The forms were new and confusing to the officials who suddenly had to refer to “Partner A” and “Partner B” rather than “bride” and “groom.” There was a lawsuit filed at the time by a person who claimed she was being discriminated against when she was denied the title of bride on her County form; that lawsuit was rejected by the court.

License in hand, we returned to that municipal site, which resembles a public restroom in a National Park or some other small official structure. Others there waiting in line to get married appeared to have legal concerns such as impending prison sentences or threats of deportation. Some were dressed in prom-like costumes, but most were not. We wore jeans and somewhat European un-tucked shirts. Unlike what was happening at the same time in Beverly Hills and West Hollywood, we were the only gay/lesbian couple at the East LA Country Clerk’s Office that day. Though we conspired briefly to keep them away, we realized that would be mean, so our six parents were there: my white feminist mother, a retired high-school teacher and former activist; my African-American conceptual artist father; my Italian-American stepfather, a onetime newspaper reporter who later worked in government; my young stepmother who emigrated from El Salvador; Alex’s Russian Jewish mother, a former high school teacher who was once a model and is now an anti-bullying activist; and Alex’s Cuban/Puerto Rican father, a retired Spanish professor, poetry translator, and innovator of Chicano Studies. The eight of us were not quite the picture of normativity as we gathered around a plastic trellis archway adorned with dusty fake flowers under fluorescent lights before a confused Justice of the Peace in a black robe behind a clunky podium bearing the State Seal of California, which depicts an Amazon warrior princess, a bear, and incoming Spanish ships. The official stumbled each time she said Partner A and Partner B, having to upend a script she had no doubt delivered a thousand times. Nor could she pronounce our names. The declaration of marriage, one of the key examples of the performative speech act that we trace from J.L. Austen through Judith Butler and the rest, felt particularly provisional, uttered for the first time, not at all standardizing. “Husband” and “wife” were obliterated in favor of the more neutral “spouses.” I giggled the whole time, because it was all so charming. Later we had mojitos with our families, then went home and had gay sex.

Rather than a sense of conservative assimilation on that day, I felt more like we were doing our part to peacefully destroy the sanctity of marriage. My second defense of marriage is this: when we do it, we are redesigning a pillar of heteronormativity and doing damage to the deleterious fidelities that bind gender, law, language, and the family. Many in the public sphere scoff at the conservative conjecture that same-sex marriage could lead to polygamy, bestiality, and all manner of redefinitions. In this one instance, I wonder if they could actually be right.

For me love is you and you love me too

Boyfriend is really a silly word

Let’s share a bed

From death back in time ‘til the day we were wed

Gay marry me, gay marry me, gay marry me

Hey-wa hey-ya

—Gay Shaman/Gay Marry Me, My Barbarian’s concert performance California Sweet & the 7 Pagan Rights (2005)

“My Barbarian, always ahead of the law, always a step ahead,” I said while singing at the symposium, referring to this pretty little song that was part of a story about a man who marries a gay polar bear, which borrowed from Native American cultural forms, tastefully, but in a way that I probably wouldn’t do now. In its original concert, that number was performed right before our a anti-Pentagon witch-opus finale about the 7 pagan rights; and after a ballad about gay marines sharing a last night in Iraq, which followed a lively sax-y piece about the deadly labor conditions of drug-dealing cruise-ship dancers in San Diego, which was mixed with a short disco dance, which came after a cool pop song/monologue about an empowered, sexy older straight woman in Santa Fe, which was preceded by a showstopper about the coerciveness of realist acting, which came after a synth-y rock anthem about ancient destroyed cities, which followed an opening incantation of wartime druids.2 My collaborators and I were in a constant state of mythic reaction to the Bush Administration in those days, and the Rove crew had pushed anti-gay-marriage legislation as a key to their 2004 continuance, so that inevitably ended up on our list of references. When we performed this concert, gay marriage seemed far from permissible. We were invoking it as a representation of resistance. The song goes on to say:

So what if our union dissolves the state

Small price to pay for my soulmate

In the future’s apocalyptic-post

I’ll be with the man I love the most

The song managed to play both the radical negativity attributed to queers and the romantic nihilism of queer aesthetics, while warmly and sincerely embracing a positivist outcome: an ambivalent performance.

It’s not only queer sex that we rightfully protect with our identity constructions, but also queer love, in its various forms, which of course include many non-procreative partnerships. The legal language that condones these relationships and condemns others tends to speak annoyingly of “loving” and “committed” “couples.” While it is injurious to all that rights and access are unevenly distributed, I would rather the state move in the direction of recognizing queer love and queer commitments than maintain the positions it held on even those matters when we were kids, when anyone other than today’s kids were kids. I recently read an essay Gregg Bordowitz wrote about Act Up in 1987, where he declares: “As a twenty-three-year-old faggot, I get no affirmation from my culture.”3 I was a little younger than that then, and though I would have put it differently, I felt pretty much the same way. In the public discourse, even beyond marriage, there has been a distinct shift of tone. A twenty-three-year-old faggot today might even get just a little bit of affirmation from the culture.

The USA affirms many worse ideas than queer love. My third defense is that putting queer love in public may contribute to the common good. Many queer relationships, with their provisional negotiations of power dynamics, sex roles, extramarital relations, and ways of maneuvering around family structures and old prohibitions, might be very useful political models. Queer love can be part of the subjective experience that exceeds agency and its requirements. “We need to recover today this material and political sense of love, a love as strong as death. This does not mean you cannot love your spouse, your mother, and your child. It only means that your love does not end there, that love serves as the basis for our political projects in common and the construction of a new society. Without love, we are nothing.”4 This tender passage from Hardt and Negri reminds us that same-sex marriage is not the problem, but that where it exists, it is only the beginning of a solution.

I’m a maid who would marry and will take with no qualm

Any Tom, Dick or Harry

Any Harry, Dick or Tom

I’m a maid mad to marry and will take double-quick

Any Tom, Dick or Harry

Any Tom, Harry or Dick

—“Tom, Dick and Harry,” Kiss Me Kate (1948)

I ended that performance, as I end these notes, with this quippy sexy bit from Cole Porter, the brilliant closeted author of syncopated double entendre and happy/sad melody. While referencing a disciplinary history in which the manner and placement of a wedding in a narrative defines the form itself, this send-up of Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew confirms that a sassy lass can make of marriage whatever she wants. I haven’t found marriage to be any more essentially conservative than the schools I’ve attended, companies I’ve worked for, museums in which I’ve shown work, or states to which I’ve paid taxes. At least in this institution, I chose my own partner. We are simply participating on another platform with another system, negotiating for the best outcome. While power works to order differences, differences can also work in excess of power. Queerness can endure marriage.

I’m using Berlant and Warner’s definition of “heteronormativity” here: “A complex cluster of sexual practices gets confused, in heterosexual culture, with the love plot of intimacy and familialism that signifies belonging to society in a deep and normal way. Community is imagined through scenes of intimacy, coupling and kinship; a historical relation to futurity is restricted to generational narrative and reproduction. A whole field of social relations becomes intelligible as heterosexuality, and this privatized sexual culture bestows on its sexual practices a tacit sense of rightness and normalcy. This sense of rightness—embedded in things and not just sex—is what we call heteronormativity.” Though crtically understood as a “cluster” itself, the important result is that unifying “sense of rightness.” Lauren Berlant and Michael Warner, “Sex In Public,” Critical Inquiry Vol. 24, No. 2 (Winter 1998): 59.

José Muñoz, discussing part of this work, wrote: “This performance imagines a time and place outside the stultifying hold of the present by calling on a mythical past where we can indeed imagine the defying of Christian totalitarianism, where we spin in concentric circles that defy linear logic, where one’s own ego is sacrificed for a collective dignity, where queer bodies receive divine anointment, where the future is actively imagined, where our dying natural world can be revivied, and once again, where collectively we follow our spirits.” Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York and London: New York Univ. Press 2009), 179.

Gregg Bordowitz, “Picture a Coalition,” October 43 (Winter 1987): 183.

Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Multitude (London: Penguin Books, 2004), 352.