Tenderness, unburdened sentiments, and freedom are rarely found in the cinematographic spectrum of the 1950s. Arne Mattsson’s 1951 film One Summer of Happiness already assures us with its title that we are going to see something perishable. Just as the water of the lake where the two protagonists swim glitters only on the surface, and only when the sun is going down, the moments they share in this fluid and forgiving medium are already doomed. The film’s rather predictable boy-meets-girl story nevertheless presents one trope that was scandalous for the time: nudity. And we are not just talking about contours of naked female and male bodies at play, but a clear view of erect nipples. This came as close to sex on screen as 1950s audiences were likely to see. After receiving a Golden Bear at the second Berlin International Film Festival in 1952, the movie only made it to New York City in 1957. However, it was shown in Zagreb in 1952 at Kino Prosvjeta (Cinema Education), a movie theater on the ground floor of a former military hospital on Krajiška Street. Every fifteen-year-old seeing it must have gleaned enough material for an outburst of romantic or raunchy fantasies—except for one. Antonio G. Lauer, a.k.a. Tomislav Gotovac, decided many years after One Summer of Happiness that “what was implanted in [his] artistic brain [back then] was that nudity was one of the most important things through which you can tell the world your attitude toward it.”1

Gotovac’s attitude, present in his entire body of work, was to provoke and please at the same time. It rarely abated and is echoed in contemporary correlations between artistic practice, the body, and factologies of the social. Who was this guy taking a stance for nudity in art when Marina Abramović was still a teenager, and coping in a society that condemned anything remotely unconventional (Gotovac’s 1962 performance Showing Elle was his first attempt to take off his clothes in public)? Over the last few years, several notable shows have offered new perspectives on Gotovac’s work. In the autumn of 2012, Tobias G. Natter and Elisabeth Leopold, curators of the Nude Men exhibition at the Leopold Museum in Vienna, placed Gotovac’s Foxy Mister (2002) at the center of the audience’s attention. At the time, one visitor told me that as soon as he entered the space where Foxy Mister hung, everything else faded to gray. In comparison, Robert Mapplethorpe’s Cock and Jeans (1978), also part of Nude Men, turned into just another stylized image from the Charlie’s Angels 1970s. The curators described Foxy Mister, in which a nude, aging Gotovac adopts the poses of a young female sex worker, as “ghoulish humor.” However, his nudes are more than persiflage or a parody of the constructed differences between the sexes. The artist rarely complied with categories; instead, he explored and exasperated them. And yet, Gotovac’s nudes were not widely circulated. In the spring of 2013, the exhibition Zero Point of Meaning at Camera Austria, curated by the art historians Sandra Križić Roban and Ivana Hanaček, turned to Gotovac’s early photographic work. His Heads (1960) were chosen for their implicit reflection of surrealist and nouvelle vague criticism of conformism and the church. Križić Roban and Hanaček arranged the images in the way Gotovac himself had originally intended: vertically aligned to resemble a totem, and mounted much higher on the wall than the works that surround them, as if Gotovac’s totem ruled over these other works. This detail is worth mentioning, because it is far from easy to exhibit the work of a perfectionist. Few others succeeded. A later series of photographs, also called Heads (1970), was shown at Frieze Masters 2013 by the Parisian gallery Frank Elbaz, and was curated by Gotovac’s longtime collaborator, the photographer Žarko Vijatović, and the artist Danka Sošić. Afterwards, both MoMA and the Tate inquired about organizing seminars on Gotovac for their curating staff, who were eager to beef up their Eastern European art epistemology. The Heads (1970) series depicts Gotovac in sequence: fully bearded, then partly shaven with sideburns, and then completely shaven and bald. The twelve mug shot–like portraits pay homage to the artist’s favorite troika: Godard, Dreyer, and Bresson. Gotovac’s cinephilia, combined with his unmistakably bold, bossy, brassy gestures and his slightly unsettling but attractive nudes, just might be the secret of his continuing rise. Not surprisingly, some have placed considerable monetary expectations on this rise.

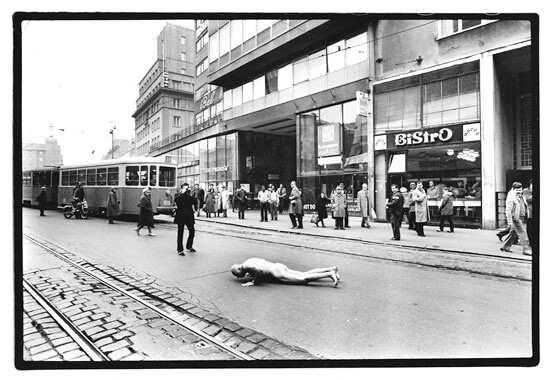

When Gotovac’s widow, Zora Cazi-Gotovac, offered the city of Zagreb the opportunity to preserve—in cooperation with the Croatian Film Alliance and the Museum of Contemporary Art—the artist’s estate at Krajiška Street 29, city administrators declined because of budget deficits. Considering that at the time, the inhabitants of some areas of Croatia, including parts of Zagreb, only had access to drinkable water by way of antiquated water pumps, it is relevant to mention other projects the city did support. Most prominent among these was a large and colorfully lit fountain in front of the National Library, built at the behest of the city’s mayor. In the face of such neobaroque techniques of power and play, one might assume that Gotovac’s work couldn’t prevail. However, three years after the city turned down Cazi-Gotovac, the mayor inaugurated a commemorative plaque on Ilica Street honoring Gotovac’s performance Lying Naked on the Asphalt, Kissing the Asphalt (Zagreb, I love you) (1981). In this performance, the artist paced the city’s main street barefoot and naked, lay down on the pavement, and graced it with his kisses. Last autumn, two bronze casts of the artist’s rather large feet where installed to commemorate the happening. Many Croatians welcomed this belated gesture of recognition. Others, some of whom were close to the artist, speculated in private about the fate of such walks of fame—about the one in St. Louis, which honors famous St. Louisans, amounting to not much more than a Wikipedia corpse; or about the one in Berlin, which honors German film stars, and which is either permanently under repair or ignored by citizens and tourists alike. Typically, these civic gestures merely give the illusion of a profitable cultural investment in provincial minds.

Instead of compartmentalizing Gotovac’s work into different categories—like performance art, body art, or conceptual art—it is a challenge worth taking up to stay with Krajiška and the operations that occurred in and from there. And it is a challenge to concentrate on his nudes. Starting with short film sequences, then passing to collage, using his body in performance and photography as well as in conceptual projects, Gotovac assembled a “total system.” According to film critic Hrvoje Turković, this kind of “total system” is a compilation of complementary works that together form an all-encompassing totality. Gotovac’s collaborators and friends love to seek explanations for his doings too, just to escape the dictum “Tom was Tom.” The total system was a “Tom system,” or in the artist’s own words, a “system of directing and viewing.” These were the favored techniques of a man who was a schooled film director and an obsessive reel consumer, who returned to his favorite scenes up to a hundred times. Gotovac made sure his art was saturated with his cinephilic knowledge and his obsession for micro-visualities that only his eye could perceive. Much of this began in 1941 when Tomislav, at four years old, moved with his family to Krajiška—just next door to Kino Prosvjeta.

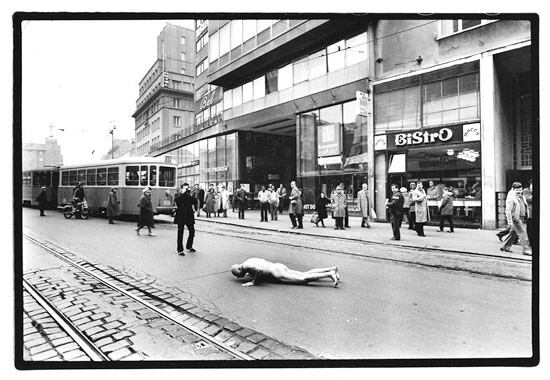

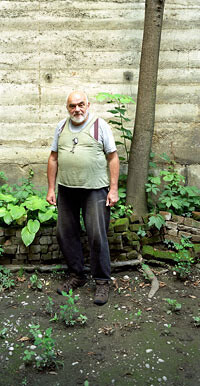

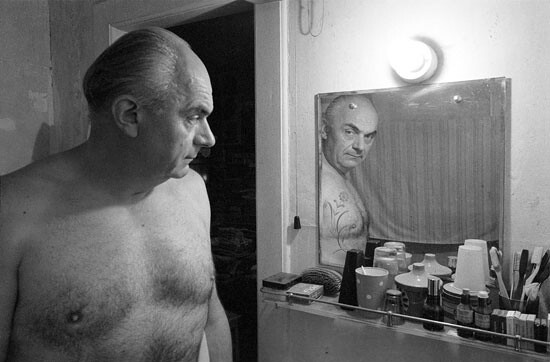

After the death of his mother, Elizabeta Beška Lauer, in 1987 (in whose honor he changed his last name in 2005), Gotovac gradually converted his residence into a space under construction, much like a Bau. The German word Bau can mean many things: a building, a tunnel, an adit, or a hole dug by a small creature. Gotovac repeatedly referred to Kurt Schwitters’s Merzbau as his point of departure. This infamous work, destroyed by an Allied bombing in 1943, was an extensive environment carved into a Hannover studio. Entering The Gotovac Institute at Krajiška today, one can still encounter the Bau principle that Gotovac so passionately followed, identifying as he did with its thrown-togetherness and outsiderism. The kitchen and the bathroom, located on one side of the apartment, were left untouched by Cazi-Gotovac and her project partner Darko Šimičić after the ERSTE Foundation provided the majority of the preservation budget in 2012. Looking at the images of the Krajiška flat in Gotovac’s After Beška’s Death (1988, photographs by Nino Semialjac), which show Elizabeta Lauer’s belongings beautifully stacked in cupboards and the artist glancing into his mother’s mirror—its decorative etchings projecting a tattoo onto his chest—it seems as if Gotovac was preserving objects she left behind, at the same time as he was producing a new order closely connected to himself and the evolution of his work. Where the trappings of petit bourgeois life—laced handkerchiefs and gold-rimmed vases—used to sit, detritus from the artist’s everyday consumer life moved in. The kitchen walls are covered with newspaper clippings, beer bottle caps, clothespins arranged into a smiley face, receipts, slips of paper, plastic bags, film posters, and other ephemera. Gotovac pleated and wrinkled tram tickets and food labels, and then pasted them together into collages (1964). He collected daily existence and inserted it into his work with much care. Every detail mattered. It is hard to understand the systemic dimension of Gotovac’s work without looking at instances when his ephemera collages turned into assemblages. His was a process of turning flatness into volume, volume into environment, and environment into being. One such instance was the floors of the flat, which Gotovac gradually filled with boxes and stacked paper, forming passages through the Bau. These passages were the intestines of the “Tom system,” processing everything that went through Krajiška. And if the flat was the abdomen around these intestines, the building itself was the body. For a time, Gotovac was the head of the property owner’s association at Krajiška Street 29. He took care of the garbage, lights, apartment maintenance, and the backyard. Described by Cazi-Gotovac as a very strong-willed and difficult person, Gotovac regularly got into disputes with the other property owners. One such dispute began when some residents wanted to cut down a tree in the backyard, for fear that its roots would damage the foundation of the building. In the end, Gotovac saved the tree.

The longstanding ViGo collaboration between Gotovac and photographer Žarko Vijatović speaks to this practice of salvaging a valued object by encapsulating it in an artwork. In a series of color photographs, we encounter Gotovac embracing and kissing the tree in the backyard of Krajiška (2008). This gesture is not one of triumph over others who are less compassionate. Rather, it is a gesture of integration. Just like the everyday objects he salvages, the tree is turned into a part of the artist’s body of work. Another series of photographs follows Gotovac around Krajiška, showing him next to a building’s trash receptacle, wearing his favorite trench coat and black leather baseball cap (2008). Despite the ravages of age and illness on Gotovac’s former physical grandeur, exhibitionism and the thrill of the unexpected are sneakily present in these images. We are not quite certain whether he is going to flash his genitals before taking the next step, or halt and perhaps make use of a walking stick we haven’t discovered in the picture yet. Gotovac was very picky when it came to choosing his collaborators; it is evident that Vijatović was one of his favorites. An earlier work, comprised of a series of black-and-white photographs depicting Gotovac roaming throughout the building at Krajiška—including the flat, the cellar, the staircase, and the rooftop—adds volume to the nude body, thereby reinforcing the significance of the assemblage as a pivotal part of the “Tom system.” Tomislav Gotovac in the Building at Krajiška 29 (1990) is again a portrayal of a man at his residence, except that this man is completely naked and his residence stripped down to its essentials. Floors, walls, light, dirt, and debris are met by skin, body hair, bare feet, and a penis. A cinematographic chronicle is silently established around these two protagonists—Gotovac and the building itself. In the cellar images, Gotovac is a giant inhabiting the basement. In one picture, his left eye is gleaming. A lurking threat is present. Upstairs, the threat dissipates and concentrated movement takes over. Gotovac’s long legs and sturdy upper body take charge. The building is not merely a prop, but an agent of assembly actively drawing the scene together, similar to Hitchcock’s eye for architecture. Only inside the apartment does the movement stop; in the stillness of privacy, the nude body is presented in detail. In one of the images, Gotovac holds a light bulb close to his penis. In the circle of light, his navel becomes prominent as well. Its dark hollowness, its hole-like appearance, challenges the penile sovereignty. Furthermore, we are meant to see that the artist is looking down at his genitals. Such an acknowledgment of his sex as self-acknowledgment is a recurring topos. It invites the beholder to insert herself into the viewing regime of Gotovac’s panopticon, adopting the role of a surveyor. It is daring to sidestep voyeurism—that island of intrusive visual joy—in favor of a far more intellectually attentive viewing. Instead of lingering on the nudity, a surveyor is expected to confront cultural frames that shape the mise-en-scène. These cultural frames are cinematography, social paranoia, and the politics of sex and the body.

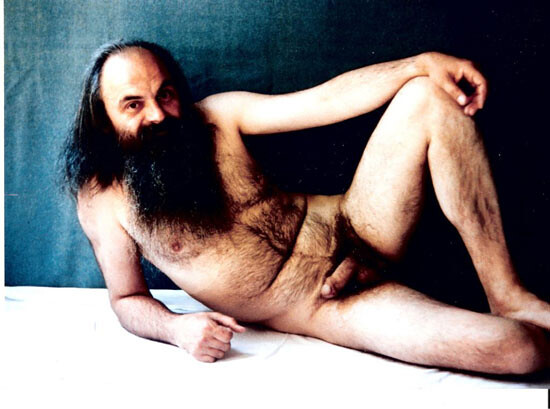

Such frames appear in many of Gotovac’s nude photographic works. The earliest is Tom, A Proposal for a Sexy Mag (1978). As a product of an accidental collaboration with Cazi-Gotovac—the first photographer Gotovac asked for assistance declined—the work is unique for many reasons. Cazi-Gotovac was not just an amateur photographer; she was also the artist’s young wife. The photos were taken in her parents’ flat—on a bed, in the shower, and in front of a window with the blinds half closed. The only piece of clothing Gotovac wears in one image is a denim button-up shirt with mother of pearl buttons—the uniform of an American rebel. Signifiers of American culture are a regular occurrence in Gotovac’s works. Here they allude to the possibility of translation into the local production of porn. One of the photos was supposed to be published in Start magazine as the first ever male pinup in Yugoslavia; the activist and Start journalist Vesna Kesić vouched for it. It didn’t happen. However, erotic or pornographic magazines were not generally marginalized in Yugoslavia. On the contrary, from the late the 1960s to the ’80s, Yugoslavia’s media market was probably the most progressive in Eastern Europe, if not in all of Europe. Travel and sex—the latter on screen and on paper—were the cardinal freedoms made available by the socialist regime of Yugoslavia. Erotic and pornographic magazines had a large circulation and were only lightly censored. Their objective was to entertain and educate while tearing down conservative and religious morals in order to give rise to others.

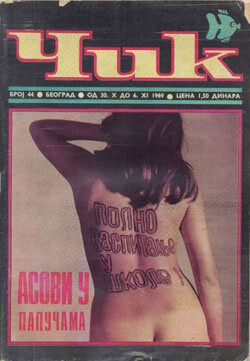

Gotovac read and collected Čik and Start—the former was published in Belgrade, the latter in Zagreb. The girls on Čik’s cover were partially nude, and the magazine’s focus was sexual education, with topics ranging from contraception to love advice to sexually transmitted diseases. An issue of Čik published in the autumn of 1969 had a rabble-rousing cover: a brunette baring her back and part of her behind was accompanied by the slogan “Sexual education in schools.” Created in a socialist studio, the image had a Woodstock feel. Start, published by Zagreb’s influential Vjesnik publishing house from 1969 to 1991, was a bigger, bolder publication. With quality journalism, it turned its readers’ attention toward politics, cultural criticism, emerging writers, art, and sex. Following the Playboy model, Start always had a nude girl on the cover, and the centerfold was a pinup girl. However, in other ways Start was different: neither strictly political nor strictly porn, neither East nor West, but particularly masculine and particularly feminine. The depiction of women as readily available visual objects of lust was obvious, but to criticize this is tedious, and it limits us to a purely feminist approach. It is worth noting that being liberal (as well as loud and lewd, some might add) wasn’t restricted to the media in Yugoslavia. It was the territory that the whole country claimed for itself, including its art. We may see Tom, A Proposal for a Sexy Mag as an echo of this. Or we may follow Leopold and Natter in their understanding of Gotovac’s nudes as a parody of the sexes. Then again, “Tom was Tom”—he was the sole director of the manner in which he wished to be viewed.

In looking at the nine images from the series Tom, A Proposal for a Sexy Mag, it is difficult not to see the intimacy between the two collaborators and lovers. Throughout the series, Gotovac has an erection. Similar to the girl’s erect nipples in One Summer of Happiness, which foreshadow sex that we don’t get to see, the artist’s erection takes center stage here. Gotovac told Vijatović that being photographed by his wife aroused him. The displayed hard-on is devoted to his wife and also to us as viewers. We get to see what Gotovac sees, what Cazi-Gotovac sees. While taking a shower in one of the images, Gotovac’s eyes are turned up in ecstasy. In the next one, he holds his erect penis and lets the water flow over it. We imagine him enjoying the cooling, sustaining effect. In the next image, the artist has turned his back on us. We see his hairy derriere, and since one leg is lifted, the slit between his ass cheeks is readily available. Yet, inside this vortex of sexual offerings and sexual offers, penetration is not an option. It would break the act. Surprising as it may be to our gendered gaze, the camera does not serve as a sexual tool, nor is there a phallus one can identify with in order to dominate the situation. This might be the secret of the allure of Gotovac’s nudes: they are not about sex, but sexuality, sexiness, and seduction. They are about lust and desire joined and sustained. Mehdi Belhaj Kacem’s book Être et sexuation develops the subversive idea that the joining of lust and desire is not just good for escaping the death drive. It also draws us nearer to the nucleus of sexuality unspoiled by language.2 He calls such a reconciliation with the sexual nature of the other (whoever that might be) a “singularity.” The assumption that “men are much harder to view” is undermined in Tom, A Proposal for a Sexy Mag. Whereas a penis figures as a turnoff to many female and male viewers alike, in the work of Gotovac it serves to assuage us, making sure that our fascination does not run dry. Gotovac does not impersonate travesty, but incorporates sexuality and sexiness as transverse social attitudes. We are directed toward visual pleasures that are not coded yet. They cultivate the singular. Gotovac is our gentleman next door.

Then again, he lived in a country that sanctioned sex in the media but prosecuted any deviation. In 1980 two years after Tom, A Proposal for a Sexy Mag, Polet, the weekly magazine of the League of Socialist Youth of Croatia, achieved a publicity coup. It featured a cover story showcasing Milan Šarović, the goalkeeper of the football team Dinamo Zagreb, in the nude. The story was dubbed “Gol-man” (the man undressed) and was accompanied by photographs taken by Mio Vesović, who helped create Polet’s nouvelle vague aesthetic. In the pictures, Šarović enters and exits a pool without trunks, the embodiment of bold athleticism. Another picture captures Šarović’s legs being massaged by a therapist. Since the goalkeeper’s torso and head are left out of this image—a practice typically reserved for female nudes—it is at least as provocative as the full nude picture. After a court ruled that the story was pornographic, the issue was withdrawn from newsstands. The court decision provoked outrage among intellectuals, especially feminists, with the writer Slavenka Drakulić arguing in the next issue of Start for egalitarianism in the naked body market. The root of this initial court ruling and subsequent scandal can be found in the cultural script that dictates the correct behavior of football players, a script that is still in force today. It prescribes that a football player must be an idol for the youth. And as Milutin Baltić, the secretary of the Central Committee of the Croatian Alliance of the Communist Party, flagrantly put it, the youth do not idolize a pinup, but “jerk off to it.” Although there is an eminent difference between a football player taking off his clothes in a magazine (some say unknowingly), and a football player coming out, a diachronic comparison points us to the regulation of the corrupted relationship between football and its choreography of male sexuality. To this end, the current case of the German football player Thomas Hitzlsperger, who openly spoke about his homosexuality only after leaving Bundesliga, assists us in appreciating Polet’s coming clean with the male nude. Despite the moral double standard of the Yugoslav government and its media, they did initially provide a platform for an exploration of the male nude. The images were published; they were withdrawn only after a public and political outcry. In fact, in the aftermath the court lifted the ban and helped loosen censorship. And Šarović continued his successful football career, which would be unimaginable in football today, dominated as it is by FIFA hegemony and fascist fan culture.

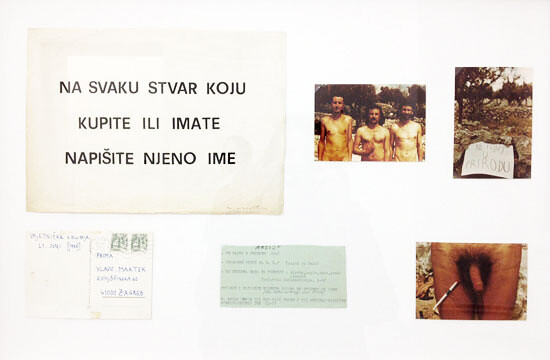

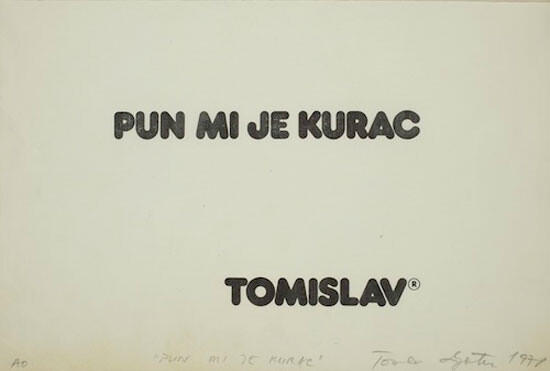

In the historic summer of 1989, the same Polet featured a “Tomislav Gotovac story.” Gotovac curated the whole issue, using it to promote his work Paranoia View Art (Homage to Glen Miller) (1989), an extensive project amalgamating his personal view on his art and the politics of others. On the cover, Gotovac superimposed a shot of himself holding open his trench coat—a glowing five-pointed star cut out of his forehead—over the letters T-O-M. His exposed penis dangles neatly below the Glen Miller T-shirt he is wearing. This Tom character—a cinephile punk—is joined by three other portraits inside the paper: Tom the security agency worker, Tom the pinup, and Tom the superhero. They all pay homage to the absurd adventures of a country facing its brutal fall, while still enjoying the last convulsions of socialism. And it is here that the pinup from Tom, A Proposal for a Sexy Mag is finally published and turned into an amusing agent of history: with slightly mocking eyes and an already softened erection, it documents the laissez-faire assertiveness of a generation that in every sense of the word has had a “dick-full.” In a wise bit of foresight, Gotovac produced several cardboards placards bearing his signature and a copyright mark under the phrase “I have a dick-full,” a colloquial expression meaning “I’ve had enough” (Pun mi je kurac, 1978). It was a tipping point for nudity as an “attitude toward [the world]” in the arts. Others joined in. In his piece Write a Name on Everything You Buy or Own (1980), Vlado Martek brought his conceptual poetry into uncharted territory when he inked “dick” on his penis. The inscription prevents the viewer from ignoring the scribbled letters, forcing her or him to experience the amusement (or shame) of lingering too long over the artist’s denomination of ownership down below. On the other hand, in their work Imponderabilia (1977) Marina Abramović and Ulay forced visitors to get stuck in the pulpiness of sexual reification by making them squeeze themselves through the vault of their exposed bodies. In An Attempt at Identification (1979), Vlasta Delimar and Željko Jerman stood naked on stage with “I” painted on each of their chests, then engaged in a tight embrace to smear the letters. This made it less tactile, but not less itchy, for viewers to surpass the obvious message and lose themselves in relishing the bodies presented. In one way or another, all of these works employed techniques of shaking up sex and stripping it away from cultural scripts. To have a “dick-full” meant more than being sick of it all. It meant unleashing being a dick to the fullest.

Gotovac in Darko Bavoljak’s film Stupid Antonio Presents (2006).

Mehdi Belhaj Kacem, Être et sexuation (Paris: Stock, 2013).

All images courtesy of Tomislav Gotovac Institute unless otherwise noted.