In the current political and social catastrophe, the denizens of the art world overwhelmingly take the position of concerned liberals, shaking their heads in disbelief at the rise of Trump, Le Pen, Wilders, UKIP, Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), Pegida, and so on. Let’s call it Wolfgang Tillmans Syndrome. The photographer, who in the run-up to the Brexit referendum launched a pro-EU poster campaign, is the perfect poster boy for the EU and the international metropolitan lifestyle it enables.1 He is clearly cultured, smart, tolerant, and empathetic—though perhaps not overly willing to acknowledge the structural violence and entrenched privilege that fosters such a subjectivity. His downloadable posters, like the “Remain” campaign as such, failed to achieve the desired goal, being up against fears and desires resistant to reasoning. That Brexit will likely hurt many of those who voted “out” more than it will hurt Tillmans has been adduced as proof of the utter irrationality of the whole thing. However, it is also clear that the likes of Tillmans have profited disproportionately from the neoliberal policies with which the EU has been, disproportionately if not entirely unfairly, identified in the minds of many (due to conservative politicians’ and newspapers’ scapegoating of “Brussels”). In this sense, there is a logic to pulling the plug, however (self-)destructive it may be. How have we gotten to this point, and how to get beyond it?

The rapidly emerging global alliance of irate middle-class Wutbürger—in Little England, in Iowa, in Saxonia—is not devoid of a certain rationality even in its most hateful, xenophobic, and homophobic manifestations. For all the differences between the Western-European welfare states and the more nakedly capitalist regime in the United States, the postwar consensus in both societies was based on an ideology of limitless growth. The working class may not have been promised jetpacks, but for decades social democrats, progressives, and socially conservative economic liberals alike held out the promise of slow but steady advance: “Your children will be better off than you.” Now that this system is stuttering, the ideology of growth has been replaced with the reality of wealth redistribution from bottom to top. This is what “austerity measures” and cutbacks in social services, health, and education ultimately amount to. For a number of decades, with the 1970s as the high-water mark, free or affordable higher education was the real-life embodiment of the rhetoric of working-class emancipation. And it actually worked, up to a point.2

The combination of stalling economic growth and ongoing ecological devastation has created a perfect storm in which various economically, socially, or politically threatened populations are actively turned against each other. This is the core business of contemporary neofascism, from Wilders and Pegida to Le Pen and Trump, and also extending to the various degrees and admixtures of fascism in the German AfD and CSU, in the Dutch VVD, in Sarkozy’s Les Républicains, in UKIP and the “Leave” camp. “Neofascism” evokes neo-styles in art, though in contrast to neo-Gothic architects, neofascist leaders and movements often refrain from publicly praising the original—or rather originals, from Italy to Germany and beyond. The differences in the repetitions are significant; for instance, in today’s financialized economy, business leaders are often vocal proponents of internationalism, rather than rallying behind those who want to build walls. Yet genealogical linkages between historical and contemporary fascisims are as apparent as a network of family resemblances between the various neofascisms.

Time and again, in country after country, (male) white voters are mobilized against an enemy who may already be inside the walls. Usually, the main enemy is immigrant populations, for whom the postwar promise of an ever improving social contract actually still bears some relationship to reality—since they start from a far more underprivileged position. Another, relatively minor adversary is “the cultural elite,” and all concerns about precarity notwithstanding, art and culture are on the winning side. Now that hymns to economic growth have been replaced by the naked upwards redistribution of wealth, art has become a crucial asset for the diversified portfolio of the 0.1 percent, and in the cultural sphere the trickle-down effect is more than mere ideology. As a result, any artistic or intellectual critique must be self-critique. Being creative and precarious in Berlin still beats being unemployed in an ex-mining town, but the two conditions are different sides of the same polyhedron. The fascists may be the others, but casting off the Bad Object will get us nowhere. We, too, are part of the problem, living large in the vanguard of destruction.

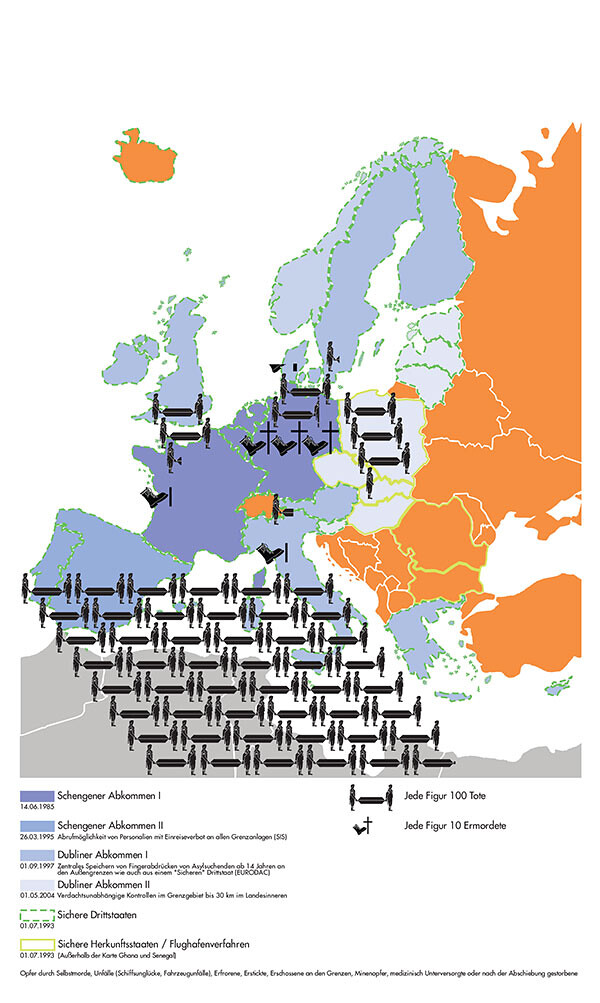

Alice Creischer and Andreas Siekmann, Festung Europa I, 2003. Digital inkjet print.

Political Economy, Political Autonomy

For many, the promise of the postwar society of affluence has been broken. Across a broad political spectrum, the recent McKinsey report Poorer than their Parents? has been welcomed as a much-needed explanation for the political turmoil in Europe and the US. According to this report, a solid majority of households (70 percent) in twenty-five “advanced economies” saw their incomes decline during the last ten years. As Fortune concluded from the data: “A huge swath of the world’s population, one that had been taught to expect their material wealth to grow through their lifetimes and across generations, has learned that this promise was a lie. No wonder voters in the rich world are being seduced by radical politics and specious solutions to their economic problems.”3 One can only assume that this report was produced by McKinsey’s No Shit, Sherlock Dept. The evidence has hardly been hidden.

But can we really explain the current upheavals by reference to an economic (and ecological) base, and relegate politics to a passively reflecting superstructure? In this line of reasoning, someone shouting racist invectives is really just concerned about their socioeconomic situation. They just need to be psychoanalyzed and their ideology approached as a symptom of their true concerns. But then, why would the fascist “distortion” be more successful than the leftist articulation of the “real” issue? Clearly, political ideology, discourse, and action attain a certain degree of autonomy by this culturalizing of the socioeconomic. While drawing strength from economic unrest, fascism has always been apt at exacerbating and exploiting the autonomy of the political from the purely economic sphere. By contrast, the Left and nominally progressive forces have often opted for economism. Whether we follow Bill Clinton in saying “it’s the economy, stupid,” or opt for Žižek’s “it’s the political economy, stupid,” there is a deep-seated tendency to reduce the political and the ideological to the economic.4 However, for 1960s Operaismo it was evident that workers’ struggle could not merely be a passive translation of underlying economic shifts. Thus, Tronti argued that the political must be accorded significant autonomy:

The foundations of the idea of the autonomy of the political are to be found in the very core of the operaist tradition, the idea that workers’ struggle drives history and not capitalist development, hence the primacy of political action. Tronti’s conception of politics departed in significant ways from what he termed “vulgar Marxism”: taking from Max Weber and Carl Schmitt the idea of political struggle as a clash of values and identities, rather than the Marxist idea of class struggle based on social contradictions. When this position was taken to its logical extreme, the autonomy of the political became the pretext for Tronti’s return to the bosom of the Italian Communist Party. Negri has been a persistent critic of Tronti’s line, which he rightly equated with “the ideology of Historic Compromise.” Therefore it is no surprise that we read in Empire that “any notion of the autonomy of the political” has disappeared, and that “the notion of politics as an independent sphere” has “very little room to exist” in our present situation where “consensus is determined more significantly by economic factors.” Negri instead opts for the other extreme, where the political is completely subsumed in the economic.5

Occupy’s “We are the 99 percent” was an example of such economism at its most liberating. However, such inclusiveness is never uncomplicated or uncontested, for within the 99 percent some classes and groups are more equal than others. Hence the embrace and further development of identity politics as a progressive version of right-wing xenophobic culturalization. In both cases, the autonomy of the political takes the form of a culturalization of social justice. This is the half-articulated meaning of the term “social justice warrior,” the preferred slur of right-wing trolls. The Left stands accused of having abandoned emancipatory action for charity on behalf of long-discriminated-against ethnic groups, women, and LGBTQ communities. Right-wing orators actually present themselves as social justice warriors, but for the white working class and lower-middle class; and in Europe, an entire white-supremacist “identitarian movement” has emerged, in which culturalism once again becomes (a desire for) fascist ethnic cleansing.6 When neofascist movements and politicians state that “they” are coming over here to take our jobs, but also to rape our women and spread crime, they not so much occlude or displace the economic as culturalize it. It is this that gives fascism its quasi-autonomous agency.

The current culture war consist of a series of clashes between right-wing identitarianism and progressive identity politics; the latter mirrors the former in that it, too, provides means of identification beyond socioeconomic categories. It does so through a strategy of universalization-through-particularization: human rights and human dignity will finally be accorded to groups that were long regarded as less than fully human, and who can now emerge into broad daylight. When this results in a fetishization of cultural codes to the neglect of the economic aspects of social justice, ostensibly emancipatory action devolves into a feel-good politics that actually relies on the persistence of systemic inequality. The suffering of others becomes a vast resource for ruling-class soul-cleansing which must be preserved at all costs. Without a broader and radically inclusive emancipatory narrative—one that can no longer rely on endless economic growth to smooth the edges—“social justice” becomes an endless obnoxious Twitter spat, an unceasing series of inane columns in liberal clickbait media arguing over who is going to hell and who isn’t. The autonomy of the political has become the autism of the filter bubble.

As the product of (mostly white) twentysomethings with college degrees rising up against their student debt, Occupy was an early instance of the protest of the educated, which today mirrors the protest of the uneducated: Sanders versus Trump supporters in the US, Corbynistas versus “Leave” voters in the UK. The Sanders campaign profited from the unrest among the educated youth (but not enough), while Trump marshals the discontent among those he himself has characterized as “the poorly educated.” In Germany, the latter would be labeled members of the bildungsferne Schichten, which one could roughly translate as “social strata at a remove from education.”7 For years, this has been code for an ex-working class that is no longer moving forward and so is often equated with waste. The term can be specifically applied to the “white trash” element (a fairly symptomatic term in its own right), but for Thilo Sarrazin, the German social democrat turned right-wing prophet of doom, the growth of bildungsferne Schichten was predicated specifically on immigration; immigrants with inferior genomes will make Germany stupid and uncompetitive.8

At the height of his success in 2010–11, Sarrazin drew an astonishing level of support from Germany’s academically educated, many of whom are plagued by Abstiegsängste (fear of economic and social decline). Highly educated Wutbürger flocked to his public appearance and shielded him from criticism. “He’s not a racist, it’s the media, they distort his words”—as an art historian who has worked for major German state-sponsored cultural organizations put it to me in 2010. This was the elite precursor of Pegida’s (that’s “Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamization of the West”) lowly “Lügenpresse” rhetoric: a mainstay of the anti-Islam and anti-immigrant movement is their criticism of the “lying” press.9 Some of those who once put Sarrazin on a pedestal will recoil in horror at what the white bildungsferne Schichten are up to these days; the most honest and the most cynical will also have to recognize a degree of complicity. Today, the “Pegida Light” that is the AfD has solid support among those who proudly—or desperately—put “Dr.” or “Dipl.-Ing.” in front of their name when they post angry comments online.

Many of those are retired, just as in the UK “[more] than half of those retired on a private pension voted to leave, as did two thirds of those retired on a state pension,” in contrast to the employed. Generally speaking the strongest supporters of anti-immigrant, right-wing, and neofascist parties and movements are the unemployed and unemployable and the retired. Furthermore, in the Brexit vote, “Among private renters and people with mortgages, a small majority (55% and 54%) voted to remain; those who owned their homes outright voted to leave by 55% to 45%. Around two thirds of council and housing association tenants voted to leave.”10 These numbers are extremely intriguing. They suggest that the situation is more complex than groups defending their wealth and privilege against change and newcomers. Clearly there is an ongoing fight over wealth distribution in a stalling economy, but its mechanisms develop a certain autonomy; they do not always transparently translate any individual’s economic self-interest. Even so: that more homeowners without than with a mortgage voted “Leave” suggests that the latter don’t give a damn; those still paying off a mortgage realize that voting “Leave” would not be in their interest, as the economy might take a hit. Those in full possession of their house (and some other capital or a pension) don’t have to care about the consequences as much—and those in council housing are truly beyond caring.

The immanent logic of the process is not one of adjusting this or that feature of the current system; it is about blowing shit up. This is ultimately what makes the current moment so eerily similar to revolutionary moments, or more particularly to moments of fascist counterrevolution. Fascism promises a triumph of Spirit over the dismal material reality of the present; the German Nazis reviled materialism and celebrated the German Geist just as today’s neofascists attack “so-called facts.”11 This triumph can only be assured by weaponizing Spirit; its enactment can only be violent.

Fear-mongering covers by both the mainstream weekly Der Spiegel (in 2007) and the far-right magazine Compact (in 2015).

Reactionary Actions

In the ruins of linear narratives, actionism triumphs. With “actionism” I refer to avant-garde practice of the 1960s, in Germany in particular, and Adorno’s critique of it. The term “Aktion” has a significant pedigree in the German-speaking world, going back at least to Franz Pfemfert’s legendary literary-political journal of the 1910s, and being revived in the 1960s in the context of art forms that were called “happenings” and “events” elsewhere: the Wiener Aktionisten and Joseph Beuys with his Aktionen, but also the post-Situationist group Subversive Aktion.12 The latter in particular can be said to represent the avant-garde blurring of the aesthetic and the political in voluntarist guise that Adorno considered to be proto- or crypto-fascist in nature. It is in this context that Habermas coined the term “Linksfaschismus.”13 Today, we see left-wing aesthetic-political actionism in the activities of the Zentrum für Politische Schönheit, for instance—but right-wing, neofascist, and Islamist varieties are far more common, and indeed hegemonic.

With former SPUR member Dieter Kunzelmann, who would later become one of the pioneers of postwar terrorism in West Germany, alongside budding student leader Rudi Dutschke and future Derrida expert Rodolphe Gasché, Subversive Aktion would have hardened Adorno in his conviction that “actionism is regressive.”14 In the later part of the 1960s, Adorno not only opposed Gehlen’s conservative overvaluation of institutions, but equally rejected the Aktionismus of young radicals such as Dutschke (who in turn regarded Adorno as a modernist mandarin who fiddled Schoenberg while Vietnam burned). Some of the Aktionisten accrued remarkable intellectual and political vitae. Bernd Rabehl would later come to embrace extreme right-wing deutschnationale positions; more recently, Frank Böckelmann has followed suit. In 2001, Böckelmann and Herbert Nagel noted in an anthology of Subversive Aktion writings:

Today, the subversives would have to say: what imposes itself cannot be real. In the era of global de-bordering (Entgrenzung) it becomes urgent to look for a singular place (nichtaustauschbarer Ort), for a form of socialization that is not represented in New York. We are always told that our wealth lies in the coexistence of a thousand forms of life. However, the decisive question is whether there is at least a single life-form that is not a priori one among a thousand options, reduced to its potentiality and thus a product of its exchangeability.15

This passage was partly quoted by Böckelmann himself in an editorial in the journal Tumult (which he coedits) in 2015, in the context of the German debates about refugees. Here, Tumult argued that the preciousness of a singular, “unübertragbare” place called Germany had to be defended not just against “New York,” but also and especially against the hordes of refugees coming from the Middle East and North Africa.16 If Tumult presents itself as a somewhat highbrow medium of reflection, a reactionary Aktionismus is in fact everywhere. Some acknowledge the genealogical connections; an example is Konservativ-Subversive Aktion founded by Götz Kubitschek, which gleefully uses 1960s tactics against some Achtundsechziger—interrupting a public appearance by Daniel Cohn-Bendit, for instance.17

Some are no doubt oblivious of their antecedents. When a young Dutchman named Donny Bonsink orchestrated a racist social-media flame-war against the black TV presenter Sylvana Simons, he justified it as a “ludieke actie”—“ludic action” having become part of everyday Dutch parlance in the 1960s thanks to the Provo movement.18 In the US context, Laurie Penny has characterized Milo Yiannopoulos—who was banned from Twitter after a similar campaign against Leslie Jones—as a “professional alt-right provocateur” distinguished by a “willingness to take pride in performative bigotry and call it strength.”19 Examples of crypto-fascist and neofascist actionism could be multiplied almost infinitely. Whenever a politician experiments with breaking a taboo and subsequently feigning bemusement at the online outrage, we are dealing with social-media actionism; actionism retooled for the attention economy. Needless to say, Trump is its master.

Portrait of Donny Bonsink, an online agitator accused of organizing a racist “hate campaign.” Photo: David van Dam.

If the methods are twenty-first century, the social and cultural imaginary often resembles an army of zombies. American evangelicals’ bathroom obsession is mirrored by German reactionaries’ outrage over “Gender Mainstreaming.”20 In Germany, media and publishers such as Compact and the Kopp Verlag, AfD intellectuals such as Alexander Gauland and former Sloterdijk assistant Marc Jongen, as well as independent intellectuals such as Sloterdijk himself are busy resurrecting old narratives and images, with more or less subtlety: crusades, Völkerwanderungen, virile black men who want to fuck our girls, and so on.21 Many believe passionately; others are simply happy to use the believers. Many believers seem not to care about the latter; in the end, the aim is to wreck with whatever means. Anything that will make the action destructive will do. Trump’s wall is the perfect example: whereas pundits critique the “plan” for being completely unrealistic, some of his supporters acknowledge that they don’t care, that this is not the point. All the insistence on how it will be built and who will pay for it barely dissimulates the fact that this is media actionism; the wall is a meme.

Meanwhile, the neofascist actionists have their perfect counterpoint in the specter or the reality—the spectral reality—of Islamist terrorism. Precisely because it is cruder, ISIS-style terrorism is an even better foil than Al-Qaeda’s. Their propaganda by the deed is the perfect mirror image of right-wing actionism: enabled by and made for social media. Here, too, there are claims to universal and sacred truth, to true traditions and traditional role models. That this version, created on the messy outskirts of Empire, is the cruelest and crudest product on the market, goes without saying. Precisely because ISIS-style jihadism is such a full-frontal attack on all that is humane, it is the prefect lever for redefining and abrogating the “Western values” that supposedly have to be defended against it.

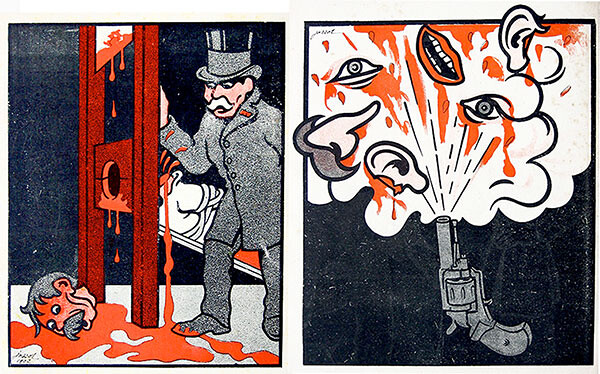

Alexander Roob has pointed out that some years before his brutal murder, the Charlie Hebdo cartoonist Charb made a cartoon for an exhibition about the late-nineteenth-century French cartoonist Gustave-Henri Jossot. In his stark linear style, Jossot made some of the most striking representations of anarchist “propaganda by the deed”: anarchist actionism in the form of suicide attacks.22 Later, Jossot sought spirituality by converting to Islam, specifically to Sufism. In Charb’s 2011 cartoon, one policeman says to another: “That Jossot is an Islamist.” The other responds: “No surprise there, each of his drawings was an assassination [un attentat].” It is clear that Charb admired Jossot, and saw himself in this artistic lineage; intriguingly, he here—however ironically—suggests a homology between jihadist terrorism and cartoons that are like attentats. To be absolutely clear, there is of course no moral equivalence between running a satirical magazine and going on a killing spree. There are however structural complicities and systemic entanglements. All sides culturalize the political: either in religious or ethnic terms.

ISIS justifies its actions, and the actions it inspires, by citing the need to bring about the final battle between Islam and the heathens foretold in scripture—but such a primitivist retro-narrative is less a serious offer at making sense of the world and finding ways for meaningful action in the sense of human praxis, than an alibi for (self-)destruction. As an apocalyptic narrative that comes with strong imagery, ISIS ideology desperately needs to produce something that at least vaguely resembles the images it conjures and the promise it proffers. This is Jonestown logic; the self-fulfilling prophecy of apocalyptic cults. This is the performativity of apocalyptic actionism: total destruction—or self-destruction as its stand-in—is its own justification, as the action makes an illegitimate order built on sand, and without any meaningful future, collapse. Après nous le deluge. In this process, ideology itself reveals itself to be something of a sham—a disinhibiting agent that comes in a variety of brands. Hence the defections of left-wing terrorist actionists to fascism. There is something to be said for Olivier Roy’s phrase regarding the “Islamization of radicalism,” as opposed to the radicalization of Islam.23

Meanwhile, the Western citizen can become an actionist in the voting booth:

Do not discount the electorate’s ability to be mischievous or underestimate how many millions fancy themselves as closet anarchists once they draw the curtain and are all alone in the voting booth. It’s one of the few places left in society where there are no security cameras, no listening devices, no spouses, no kids, no boss, no cops, there’s not even a friggin’ time limit.24

Voting for Trump is the electorate going full-on suicide bomber. On the Democratic side, Sanders, the politician who could have funneled the discontent in a more productive direction, was blocked by the DNC apparatus and Democratic primary voters (getting 45 percent of the total vote, though this in itself is not decisive in the Democrats’ “superdelegate” farce). Better to gamble on the broadly reviled Clinton having a slight edge over Trump than a candidate who is not content with decorating neoliberal business as usual with some progressive policies that look nice and don’t hurt donors.

Illustrations by Gustave-Henri Jossot printed in the satirical publication L Assiette au beurre, no. 144 (1904).

The Name Game

But the earth is a globe, of limited extent. The discovery of its finite size accompanied the rise of capitalism four centuries ago, the realization of its finite size now marks the end of capitalism. The population to be subjected is limited. The hundreds of millions crowding the fertile plains of China and India once drawn within the confines of capitalism, its chief work is accomplished … Then its further expansion is checked. Not as a sudden impediment, but gradually, as a growing difficulty of selling products and investing capital. Then the pace of development slackens, production slows up, unemployment waxes a sneaking disease. Then the mutual fight of the capitalists for world domination becomes fiercer, with new world wars impending.25

Anton Pannekoek wrote these words in 1944, in Nazi-occupied Holland. The ecological dimension is left implicit in this proto-anthropocenic scenario; nonetheless, in our current global reenactment of the year 1933, these words ring all too true. While Pannekoek’s highly linear Marxist conception of history is often problematic when he presents the triumph of communism as inevitable—after the failed revolutions of 1918–20, he had little to back this up—his diagnosis of the inevitability of breakdown, of capitalism finally meeting its limits, reads as uncannily prescient. Waxing unemployment manifests itself in the proliferation of surplus populations for which there is no place in the capitalist workforce, in an economy subject to stagnation or stagflation even as the maintenance of its current level produces a creeping ecological and social catastrophe.

In such a situation, rehashed Enlightenment criticism is not necessarily helpful—particularly when it turns a blind eye to its own preconditions and limitations. Wolfgang Tillmans’s attempt to counter right-wing rhetoric and lies (about the costs and benefits of remaining in the EU, for instance) recalls the war on Fox News by US-based comedians such as John Stewart, Stephen Colbert, and John Oliver. Colbert became a liberal household deity with his takedown of the Bush White House and Fox News’s propaganda as pliable and reality-resistant “truthiness” that plays loose with the facts and does not stand up to expert scrutiny. For those hanging on to Donald Trump’s every word, the expert is seen as the incarnation of the elite—or as the elite’s faithful servant. National security and foreign policy experts say Trump is not fit to be president; if he upsets them, he’s clearly doing something right. Experts say that crime is declining; my gut tells me something different. Or, in Britain: economists say we should remain; we’ll leave. Statistics be damned.

This rejection of expertise and of the role and persona of the expert shows how apt the current neofascisms are at exploiting the performativity of language. The connotations of the term “expert” have been adjusted to make expertise a symptom of everything that is wrong. And, much as we may reject something spouted by racists and homophobes, is there not some truth to this? After all, are those seething at expertise not themselves the perverse product of centuries of expertise in science, technology, and social policy? Who makes the Nazis?26 Sure, Fox News and Compact magazine help, but those media are themselves experts of divisiveness, and fundamentally the problem is the divisions—divisions of the social, of the sensible—that a technocratic expert culture fosters and maintains. How many of us can honestly say that they have not come to some kind of understanding or arrangement with this state of affairs? It is all the easier because the others can always be typecast as the hateful, racist, white troglodytes that many of them may well be. But again, how did we get here, and how did they get like that?

In 2010, at a summer school at the Van Abbemuseum with an international group of MA (art) students, one participant stated that “we’ll just have to move on to another country” if Holland were to become inhospitable due to Geert Wilders and Co. To which someone responded: that’s all very well, but what if “we” run out of countries to choose from? Curiously but tellingly, the language here mirrored the discourse in the German Heuschreckendebatte (or “locust debate”) of 2005, which started when the politician Franz Müntefering compared anonymous corporate investors to a biblical plague of locusts. Once a company, or a country, has been grazed off, the migratory plague moves on. The progressive version of this kind of discourse is the hand-wringing over “investors” that might be “scared off” by high taxes or political unrest. Perhaps the summer school participant had this discourse in the back of their mind; right-wing populists might choose to use the more negative locust analogy. Each of these cases revolves around the image of a rootless international elite moving from country to country, seeking out (embattled) nation-states to host it temporarily.

Before the recent upswing in migration from the Middle East, a Dutch novelist made the cringeworthy statement that “artists are the new asylum seekers.”27 This too creates a homology between artists and migrants, but a very different group of migrants; one that stands for globalization from below rather than from above. Seemingly defined largely by its negation of the nation-state, the “creative class” finds itself both the active and the passive subject of projections. Depending on the context, it is either part of a global elite or an embattled minority. In both cases, it is suspected of being vaterlandslos—and while, in the face of resurgent nationalism, it makes sense to wear one’s internationalism proudly on one’s sleeves, it is hardly an adequate response. Some of the more precarious art-world denizens in particular are well aware of—and try to act on—their quasi-class’s implication in the destructive dynamic that has unfolded across the West, but so far such critical practice is a minority pursuit. We have met the enemy, and he is us.28 But at least we’re critical, right?

Isabelle Stengers maintains that critical “denunciation fabricates a division between those who know and those who are duped by appearances.”29 While I don’t agree with Stengers’s anti- or post-critical stance, it is clear that a certain type of Enlightenment criticism is part of the problem—condemning the other as irrational may be necessary, but it is not enough. This is the problem with the Colberts, Stewarts, and Olivers, who are rightly quick to lampoon and skewer Fox News and Trump, but who seem perfectly content to make Obama’s drone warfare or Clinton’s Wall Street friendliness and hawkishness appear acceptable in the process, or to sing and dance with Henry Kissinger. Technocratic expertise and hypocriticism are two sides of the same coin. What is needed is a dialectic of critique and composition, or in Stengers’s words, artifice. Stengers is perfectly right that “we are in desperate need of artifices”—and that we need to pay close attention to naming, characterizing, personifying.30

The Left was once quite good at this, with notions such as the proletariat and the working class never being mere descriptions, but always performative articulations that generated “class consciousness.” The general strike could also be mentioned as a leftist figure or myth—and indeed communism itself. Recent successes have been checkered. The collective persona of the multitude was an important conceptual innovation, but its efficacy was limited to autonomist circles; Occupy’s 99 percent was a stroke of genius whose potential has perhaps still not been fully exploited, and the same can be said for the commons. Meanwhile, identity-based movements provide valuable and often critical sustenance to embattled minorities, but at the risk of affirming identities that were forms of profiling to begin with. What is really needed is a queering of categories, a development of transversal names that cut through divisions whose maintenance benefits the forces of reaction. That this is so much easier said than done is part of the drama. Stengers’s and Latour’s appropriation of the notion of Gaia in an anthropocenic context is also intriguing, even though it is unlikely many will get beyond the faux-reactionary name.31

For the time being, the more successful artifices are souped-up remakes from the reactionary attack: Volk, Völkerwanderung, Mexican bandits and refugee rapists, national sovereignty (rather than autonomy), and so on. Even the notion of Festung Europa, or Fortress Europe, which was once mostly used in a critical fashion by the Left, has been embraced by the actionistic and identitarian right.32 Urgent work is needed on post-work and post-growth imaginaries. The odds are not good, to put it mildly. It would help if this was at least recognized more broadly as the central challenge in the ongoing catastrophe. It is in accepting this challenge that we—intellectuals, artists, former workers, and future refugees—can at least begin to engage with the enemy that is us.

See →.

Even in a society with as little social mobility as France, as Didier Eribon’s memoir Retour à Reims (Paris: Fayard, 2009) reminds us. The book, of course, is also marked by the author’s painful sense of estrangement from his social origins, whose denizens are given to homophobia and xenophobia.

Žižek’s phrase, from The Ticklish Subject (New York: Verso, 1999), 347, became the basis and title of a 2012–13 exhibition by Gregory Sholette and Oliver Ressler.

Merijn Oudenampsen, “On the Autonomy of the Political and the Poverty of Theory,” merijnoudenampsen.org, 2011 →.

In the US, Breitbart News has embraced the European Identitarians as “hipster right-wingers” →.

A whole range of translations can be found at →.

Thilo Sarrazin, Deutschland schafft sich ab. Wie wir unser Land aufs Spiel setzen (Munich: DVA, 2010).

For the role of the Lügenpresse slogan within Pegida’s rhetoric, and in the context of German political history, see Jurek Skrobala, “Vokabular wie bei Goebbels,” Spiegel Online, January 12, 2015 →.

“Lord” Ashcroft, “How the United Kingdom voted on Thursday… and why,” lordashcroftpolls.com, June 24, 2016 →.

The classic instance is Newt Gingrich’s insistence, in a TV interview during the Republican Convention in Cleveland, that feelings trump statistics: the latter may show that crime rates are down, but people’s gut feelings tell them otherwise.

Scans of Subversive Aktion publications from 1962–66 can be found at →.

Habermas used the term “linker Faschismus” at the SDS congress in Hannover on June 9, 1967; later “linker Faschismus” became “Linksfaschismus.” For the debate between Habermas and the radical Left, see Die Linke antwortet Jürgen Habermas, eds. Oskar Negt and Wolfgang Abendroth (Frankfurt am Main: Europäische Verlagsanstalt, 1968).

Theodor W. Adorno, “Marginalien zu Theorie und Praxis” (1969), in Kulturkritik und Gesellschaft II (Gesammelte Schriften 10.2) (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2003), 760–782 (quotation from p. 776). In his attacks on “actionism,” Adorno here himself uses the impoverished and undialectical notion of “praxis” (as antithetically opposed to “theory”) that he accuses his opponents of employing.

Frank Böckelmann and Herbert Nagel, “Nachwort” (2001), in Subversive Aktion. Der Sinn der Organisation ist ihr Scheitern (s.l.: Verlage Neue Kritik, 2002), 492. Author’s translation.

Frank Böckelmann and Horst Ebner, “Gibt es wenigstens eine einzige Lebensform?,” Tumult, Fall 2015: 6.

On Konservativ-Subversive Aktion and German genealogies of political actionism in general, see Wolfgang Kraushaar, “Die Ethnozentriker, ihre Vordenker und die Deutschen,” Perlentaucher.de, April 4, 2016 →.

Kim Bos, “Donny Boysink vindt zijn ‘uitzwaaipagina’ niet racistisch,” NRC Handelsblad, May 26, 2016 →.

Laurie Penny, “I’m with the Banned,” Medium, July 21, 2016 →.

See, for instance, a typical rant by Eva Herman, a former newscaster turned mainstay of the right-wing conspiracist Kopp Verlag.

The term “Völkerwanderung” evokes the period of Germanic mass migrations that contributed to the fall of the Roman Empire. It is used, for instance, by the AfD in Karlsruhe to raise fears of a new kind of barbaric invasion by refugees.

Alexander Roob, “‘Grandioser Biß’ oder ‘Verdammter Schlag in die Fresse’ ? ————— Abdul Jossot trifft Charlie Hebdo …. und die FAZ haut daneben,” meltonpriorinstitut.org →.

Cécile Daumas, “Olivier Roy et Gilles Kepel, querelle française sur le jihadisme,” Libération, April 14, 2016 →.

Michael Moore, “5 Reasons Why Trump Will Win,” michaelmoore.com →.

Anton Pannekoek, Workers’ Councils, 1946. Available at marxists.org →.

Among Mark E. Smith’s not universally helpful answers to that question in The Fall song of the same name (on Hex Enduction Hour, 1982) were “bad Tele-V,” “balding smug faggots,” “intellectual half-wits,” and “buffalo lips on toast, smiling.”

Interview with P. F. Thomése, “Kunstenaars zijn de nieuwe asielzoekers,” Ad Valvas, May 15 2013, 16–18 →.

As Walt Kelly’s Pogo put it.

Isabelle Stengers, In Catastrophic Times, trans. Andrew Goffey (Lüneburg: Open Humanities Press, Meson Press, 2015), 74.

Ibid., 144.

Ibid., 43–50; Bruno Latour, “Waiting for Gaia: Composing the Common World Through Art and Politics,” bruno-latour.fr, 2011 →.

“‘Festung Europa’ von Gegendemos Begleitet,” May 16, 2016, MDR Sachsen.