This text was originally written for the e-flux project Superhumanity, in response to the 2016 Istanbul Design Biennial, which was entitled “Are We Human?”

The EU Buffer State

Asking ourselves the question “Are we human?” in the context of Istanbul today forces us to confront the inhuman design of the European Union. Only a few years ago, Turkey was still in the race to become a new EU member state, a bid that was blocked due to, on the one hand, the regime’s brutal crackdown on press and any other form of opposition, and on the other, the strengthening wave of European xenophobia that distrusted a future member state in which Islam was the predominant faith.1 Instead, in the context of the current refugee crisis, Turkey has been turned into an EU buffer state: the outer frontier of the supranational project which now operates as the new extralegal border. Only 72,000 preselected Syrian refugees, out of the 2,700,000 currently in Turkey, have been allowed passage through.2

This transformation of Turkey into an EU buffer state comes at a high price. First, there is the three billion euros that the EU has handed over to Erdoğan’s regime to stop the flow of asylum seekers. The second cost is that of our supposed “humanity.” Creating a political dependency on the regime of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP) means that the EU is directly implicated in the legitimization of a regime that has long waged a ruthless war against its Kurdish population in Bakûr (Northern Kurdistan, in southeast Turkey), while shamelessly persecuting all civil opposition: from activists and comedians to journalists and academics, to its opposition in parliament, whose immunity from prosecution was recently lifted.3 And after the failed military coup of July 15, lists for a large-scale purge of the legal and academic professions were ready to be deployed instantly. It should not surprise us that Erdoğan has occasionally sidestepped the messy work of caring for refugees and proceeded directly to shooting them instead, all in order for the EU to keep its claim as protector of human rights intact by simply outsourcing violations to its buffer state.4

The three billion euros handed over to the regime perversely suggests that it provides some kind of safe haven. It might not have been intended to bolster Erdoğan’s ever growing military apparatus, but it does provide for its ethical legitimacy. The EU sponsors regional human rights for its member states while sponsoring bullets for its buffer state. And while ultranationalist and fascist parties within the EU take every occasion to frame Erdoğan’s regime as “Islamofascist,” the authoritarian governments of Hungary (led by Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz party, which already in 2014 declared its model to be that of “illiberal democracy”) and Poland (which changed its judiciary overnight after the Law and Justice Party won elections in 2015) effectively emulate the Turkish regime, rather than distinguishing themselves from it.5 The EU’s buffer state shows what we can expect when the governments of the French Front National and the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ) take charge. The buffer state is not an exception to the EU: it is the prototype of the new European authoritarianism to come.

Transdemocracy Rising

The design of Erdoğan’s EU buffer state is a paradigm through which we can understand the changing design of the European Union as a whole. While ever growing ultranationalist and fascist parties within the EU pretend that the Erdoğan regime is their nemesis, little differentiates them. The abuse of the “War on Terror” to implement systematic racist administrations, the disregard of an independent judiciary, and the relentless drive to isolate if not simply eliminate the opposition is common to far-right regimes on both sides of the Union’s border. The annual trips of representatives of European ultranationalist parties to a personal audience at the Kremlin are a further sign of how the far-right is uniting.6

But there is a counterforce to the Erdoğan regime as well, one that does not simply oppose its current rulers, but questions the very structures of power the regime represents. It is not by chance that it is the People’s Democratic Party (HDP) that led the Erdoğan regime to lift parliamentary immunity. Ever since its founding in 2012, HDP representatives have been targeted by the Erdoğan regime as members of a party with links to “terrorist” organizations, and much of the harassment and disappearances of its representatives and members, the campaigns of intimidation and even bombing of the party’s headquarters, have been revealed as having links to the regime.7 This oppression has only worsened since the party endured the regime’s violence through two elections, in June and November 2015, when the HDP managed to pass one of the world’s highest electoral thresholds of 10 percent both times.8

So what exactly does the supposed “terrorism” of the HDP consist of? The first charge relates to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which has waged a guerrilla struggle against what it considers as the Turkish colonization of Northern Kurdistan since the PKK’s founding in 1978. That the HDP strives for the protection and recognition of the political and cultural rights of ethnic minorities—such as Kurds, Alevis, Armenians, Yazidis, and Roma peoples9—and is partly inspired by the political philosophy of PKK founder Abdullah Öcalan has proven enough for the regime to declare the HDP and PKK one and the same.10 Nevertheless, membership and voter turnout has proven that the HDP has the potential to unite a radically diverse constituency consisting of social groups that until now were left a political vacuum: progressive Turks as much as progressive Kurds; religious constituencies as well as secular ones; rural traditionalists and urban youth.11 HDP co-chair Figen Yüksekdağ describes the attempt to create a party that could unite these various social segments in the face of increasing authoritarianism:

The HDP was established as the party of all oppressed and all peoples. All factions find a voice in the HDP … It is difficult to bring together sections of society so different from each other, but as the HDP we always believed in a unified movement of the oppressed in these lands. That is why the HDP was established, so our success and effect on society is a result of this unifying power.12

The HDP mediates between the imprisoned PKK leader Öcalan and the regime, and also directly engages with Öcalan’s political philosophy. For these reasons it would be easy to suggest that the HDP and PKK were indeed one and the same. But the fact remains that the HDP itself is not an armed movement. It wishes to achieve what it refers to as new forms of “democratic autonomy” on a nationwide level, through a combination of parliamentary representation and intersectional grassroots mobilization.13 And this is the real “terror” that Erdoğan fears: the combination of emancipatory ideology and popular mobilization that drives the HDP’s agenda for democratic autonomy, women’s and LGBT+ rights, and radical ecology. In its political program, the HDP describes its ideal for an intersectional “we”:

We are women, We are youth, We are the rainbow, We are children, We are defenders of democracy, We are representatives of all identities, We are defenders of a free world, We are protector of the nature, We are builders of a safe life economy, We are workers, We are laborers, We are the guarantor of social rights.14

Erdoğan doesn’t fear an opponent who merely wants to usurp his power; rather, he fears one who rejects the very organization of power that his regime represents. In other words, Erdoğan’s biggest dream is for the HDP to come to parliament armed to the teeth, for this would allow him to dismiss the opposition easily. But the HDP’s agenda is one that aims to challenge the design of power all together.15

What the HDP describes as “democratic autonomy” cannot be achieved through parliamentary elections in a nation-state alone. Instead, democratic autonomy aims at a new ideal of democratic self-governance that takes multiethnic and multireligious municipal constituencies as its political foundation.16 This is what the HDP refers to as the “local assemblies in our neighborhoods,” which it considers the foundation of a future decentralized network of self-governing municipalities that could effectively resist the increasing centralization of power by the Erdoğan regime.17 The aim is to establish a decentralized confederation of self-governing neighborhoods and municipalities, represented in regional assemblies within a democratic Turkish state. This is a “dual-power” vision, consisting of parliamentary representation on one hand, and local assembly-based representation on the other18:

The party wants to shift from Turkey’s current centralized structure to a highly decentralized one, with elected regional assemblies that incorporate the principles of “self-administration” and representation of “all ethnic identities.” HDP-advocated new Turkey should be based on the equality of all peoples and religions, and should signal the end of state nationalism.19

The HDP requires that 50 percent of its representatives be women and 10 percent of its membership come from LGBT+ communities. In this way the HDP takes responsibility for the structural recognition of a plurality of political subjects, rather than catering to a specific ethnic group.20 Essentially, the HDP is a transitional party: on one hand, it aims to “transition” politics from an identitarian foundation to an intersectional foundation; and on the other, it aims to transfer state power to local municipalities in order to make the project of democratic autonomy a reality. The goal is not to take power as a party, but to establish—through the party—a confederation of local assembly-based structures of self-governance. It is this paradigm of democratic autonomy that is articulated in the HDP’s “We,” which breaks with the repressive identitarian nationalist politics that has plagued Turkey ever since the fall of the Ottoman Empire. The HDP’s vision opens a realm for a new diversified culture of the demos—or, in plural, demoi—to emerge.

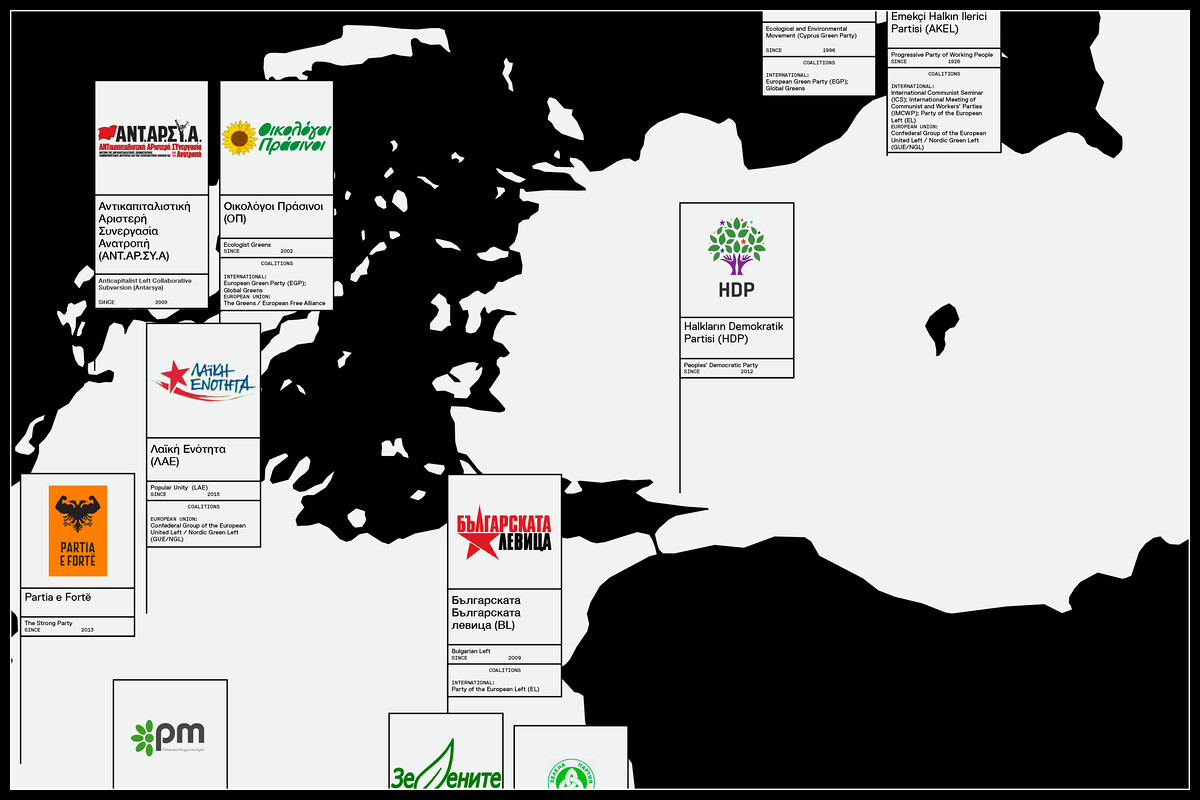

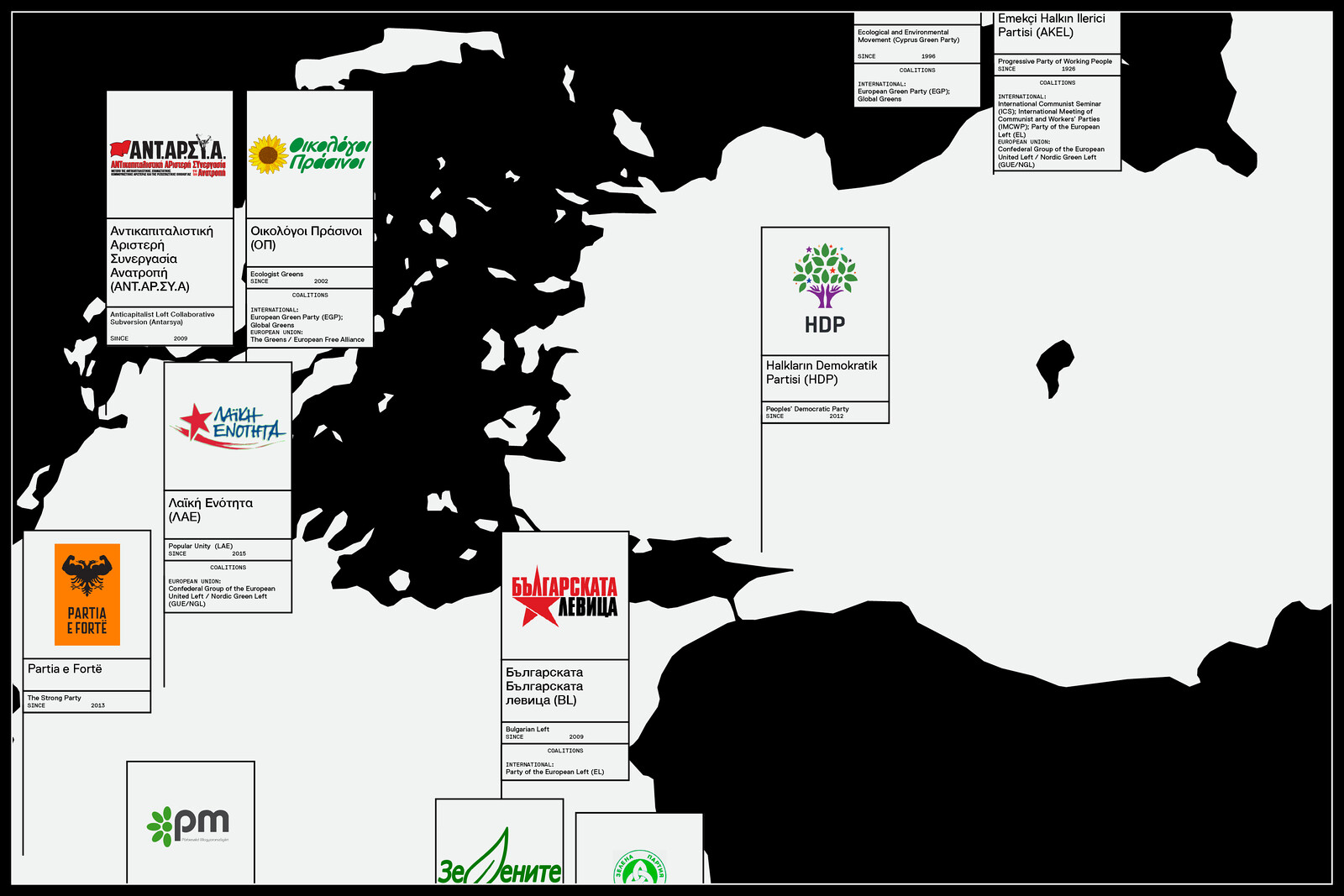

It is this shift from the politics of nationalism and statism to a politics of the demoi and democratic autonomy that reveals the ideological frontline we in Europe face as well. If the Erdoğan regime is the equivalent of Orbán’s authoritarianism in Hungary, or the Law and Justice Party’s shameless takeover of the judicial system in Poland, or the regimes-to-come of the Front National and the Freedom Party, then the equivalent of the HDP are the new forms of political parties and pan-European platforms emerging from the continent’s crises: from the rise of Podemos, which has replaced the “party” with the “circle,” to the Icelandic Pirate Party’s support of a new crowd-sourced constitution; from the rotating co-presidencies of Catalunya’s Popular Unity Candidacy (CUP) to the project for a new borderless Europe propagated by the Swedish Feminist Initiative.21 In the same spirit as the HDP, these movements have interrogated the very structures of power they are up against, refusing to replicate the oppressions of their opponent. They no longer take the form of the party, state, or capital—they are the demoi of a rising transdemocratic movement. That is why Yüksekdağ, well aware that she stands on this new frontline, generously said:

Given the crisis of the capitalist system, we see that suppressed people in Europe are also seeking alternatives. That is how Syriza and Podemos emerged … In an increasingly connected world, all these social movements influence each other and are connected. The victory of Syriza in neighboring Greece influenced the workers of our country.22

New Unions

The crises of the European Union are amplified in the crisis of its buffer state on the Bosphorus. We are confronted with two competing scenarios: on one hand, authoritarianism, racism, and fascism; and on the other, new intersectional forms of democratic autonomy and transdemocracy.23 The first road is one we have walked many times before: it is that of regression in the form of brutal economic exploitation and ultranationalist rule. Regimes and parties across Europe are lining up to follow this historic example. The second road is one we have hesitated to walk many times, for it is one with an uncertain outcome.

In the past we have called this road “revolutionary socialism” or “internationalism.” It has left its mark all over world history, from the Paris Commune to the early Russian soviets, from pan-African liberation movements to the alliance of workers and students in May ’68. Today, social movements such as the Gezi Park uprising and Nuit Debout in France are the sparks that remind us of its promise of egalitarianism and collective emancipation. The HDP’s gesture of solidarity towards progressive movements in Greece and Catalunya, Basque Country and Spain, shows us the possibilities for new transdemocratic alliances—new unions—and raises hopes for forms of being-human that cannot be reduced to a degraded humanity that sells us regional human rights under the auspices of authoritarian regimes.24

The question of whether the HDP’s new political paradigm of democratic autonomy can be shared across Europe needs of course to be addressed. One cannot negate the specificity of the history, geography, and culture that led to a complete rejection of the nation-state in a region where its construct is interlinked with a long history of colonization, one-party rule, and religious doctrine. Nonetheless, the HDP’s transitional-party strategy—moving power from government to municipalities, while remaining faithful to larger ecology of new transdemocratic movements throughout Europe—initiates a process that can help us unionize anew.

This process revolves around the possibility of a self-questioning form of politics, one that does not take power for granted, but ceaselessly interrogates its very foundations. As Judith Butler wrote, this process seeks to “devise institutions and policies that actively preserve and affirm the unchosen character of open-ended and plural cohabitation.”25 While one union is disintegrating, the possibility of a new union is right in front of our eyes, ready to be embraced. The HDP and its allies tell us loud and clear: we collapse or we unionize. Europe will be transdemocratic, or it will not be at all.

Jürgen Gerhards and Silke Hans, “Why not Turkey? Attitudes towards Turkish membership in the EU among citizens in 27 European countries,” Journal of Common Market Studies, 2011: 741–66 →.

“EU-Turkey statement,” European Council, March 18, 2016 →.

Matthew Weaver, “Turkey rounds up academics who signed petition denouncing attacks on Kurds,” The Guardian, January 15 2016 →. On the lifting of immunity, see the article by Democratic Peoples’ Party (HDP) co-chair Selahattin Demirtaş: “Free Speech Isn’t the Only Casualty of Erdoğan’s Repression,” New York Times, April 13 2016 →.

Patrick Kingsley, “Turkey is no ‘safe haven’ for refugees—it shoots them at the border,” The Guardian, April 1 2016 →.

Sylvie Kauffmann, “Europe’s Illiberal Democracies,” New York Times, March 9, 2016 →.

See Luke Harding, “We should beware Russia’s links with Europe’s right,” The Guardian, December 8, 2015 →.

See Scholars for Justice and Peace, “Report on Recent Incidents of Violence against HDP and Kurdish citizens in Turkey,” 2015 →.

Guney Işıkara, Alp Kayserilioğlu, and Max Zirngast, “Erdoğan’s Victory by Violence,” Jacobin, November 2, 2015 →.

Fehim Taştekin, “Turkey’s minorities join race for parliament,” Al-Monitor, April 10, 2015 →.

At the New World Summit in Utrecht in January 2016, Dilek Öcalan, a representative of the HDP, gave a lecture on the theoretical relationship between Öcalan’s concept of democratic autonomy and the political work of her party. See → (starting at 1:03:35).

Harriet Fildes, “The rise of the HDP – elections and democracy in Turkey,” Open Democracy, June 3, 2015 →.

Pinar Tremblay, “Kurdish women’s movement reshapes Turkish politics,” Al-Monitor, March 25, 2015 →.

At the New World Summit in Rojava in October 2015, Katerin Mendez, a representative of the Swedish Feminist Initiative (F!), gave a lecture on the concept of intersectionality as developed by Kimberlé Crenshaw, in relation to the work of her own party as well as to the Kurdish women’s movement. Mendez defined “intersectional analysis” as a way “to see how rights, opportunities and the ability to influence society actually look like for different groups.” See →.

“HDP’S Election Manifesto,” April 2015 →.

Cihad Hammy writes in this regard: “Erdoğan’s politics and Ocalan’s politics collided head on when the HDP, embracing a revolutionary and democratic politics, scored a great victory in the June election, surpassing the Turkish parliament’s 10% threshold. This impressive performance temporarily stalled Erdoğan’s ambitions, hence the subsequent escalation of conflict and the brutal crackdown on the Kurdish movement ever since. Erdoğan terminated the peace process and launched a war against the popular base of the HDP. In reaction to this war people organized local assemblies and declared self-rule all over North Kurdistan.” See Cihad Hammy, “Two visions of politics in Turkey: authoritarian and revolutionary,” Open Democracy, August 20, 2016 →.

For more elaborate texts on the concept of stateless democracy in the writings of Abdullah Öcalan and other Kurdish activists, with an emphasis on its practice in the autonomous region of Rojava, West Kurdistan (Northern Syria), see Stateless Democracy, eds. Dilar Dirik, Reneé In der Maur, and Jonas Staal (Utrecht: BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, 2015) →.

See “Who Are We” at the HDP website →.

“Dual power” here refers or course to the Russian revolution of 1917, when the government was taken over by political parties that had previously been pacified in the Duma, in alliance with the new Moscow soviets. Together they established a structure in which the Provisional Government and the soviets shared power.

“HDP vows to ‘realize democratic autonomy’ across Turkey after legislative election,” Nationalia, April 22, 2015 →.

Mona Tajali, “The promise of gender parity: Turkey’s People’s Democratic Party (HDP),” Open Democracy, October 29, 2015 →.

For Podemos in its own words, see Eduardo Maura, “Europe needs to change—and using grassroots democracy is how we do it,” The Guardian, October 13 2014 →.

Tremblay, “Kurdish women’s movement,” Al-Monitor.

The concept of transdemocracy emerged through a conversation among Renée In der Maur, Dilar Dirik, and philosopher Vincent W. J. van Gerven Oei. It takes Öcalan’s concept of democratic autonomy and other related forms of nonstate self-governance and turns them into a methodology—a series practices of transitional politics.

See also the debate “We, The People of Europe,” held on June 2, 2016 at the conference “Re:Creating Europe” in De Balie, Amsterdam. During the debate I proposed an artistic campaign entitled New Unions to several organizations and practitioners whose work is related to the concept of transdemocracy, including Slawomir Sierakowski (Krytyka Polityczna), Costas Lapavitsas (Institute for New Economic Thinking), and Angela Richter (theater artist).

Judith Butler, Notes Towards a Performative Theory of Assembly (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015), 112–13.

I would like to thank Sven Lütticken, Vincent W.J. van Gerven Oei, Renée In der Maur and Younes Bouadi for their support in writing this article. My gratitude goes to iLiana Fokianaki, founder and director of State of Concept in Athens, where on June 21 2016—together with Despina Koutsoumba, Quim Arrufat, Maria Hlavajova, Angela Dimitrakaki and Van Gerven Oei—we began to unionize anew. © 2016 e-flux and the author