Thoughts on Taiwan’s Losheng Preservation Movement from a Latecomer to the Cause

On the morning of December 3, 2008, the Losheng Preservation Movement—ever expanding since it began in 2002—set out to protest a joint proposal made in 1994 by Taiwanese state and local political forces to relocate the Xinzhuang metro depot to the Losheng Sanatorium site, which housed patients with Hansen’s Disease, formerly known as leprosy. After numerous petitions, negotiations, demonstrations, and protests, the Losheng Preservation Movement still failed to change the government’s decision to demolish more than 70 percent of the sanatorium. The morning of December 3, 2008 was when the government of Taipei County planned to send massive numbers of police to clear out all anti-relocation protesters, so as to assist the Taipei Department of Rapid Transit Systems in erecting a fence around the sanatorium in preparation for the construction of the new metro depot. To fend off this forced dispersal, over a hundred sanatorium residents, students, and members of the general public had occupied the space in front of the sanatorium’s Zhende Dormitory the night before. Immediately after the police dispersed all of the demonstrators, construction fences were erected, and the demolition of the sanatorium’s housing began promptly the following day.

Although it was unable to prevent the demolition of the Losheng Sanatorium, this seemingly “failed” preservation movement stirs us to reflect on its multiple dimensions and complex meanings—meanings that ripple out far beyond the sanatorium itself. Even after 70 percent of the sanatorium was demolished, we are confronted with the question of whether there exists another invisible yet permanent Losheng Sanatorium beyond the visible establishment. Are we participants in the construction of this invisible sanatorium?

As someone who never participated in the Losheng Preservation Movement, and as a nonprofessional who lacks extensive medical knowledge of Hansen’s Disease, how did I come to stand before the remnants of the sanatorium in 2013, long after the preservation movement’s heyday? How did I take these remnants as a starting point to create my four-part film Realm of Reverberations, as well as other follow-up works? Before taking you through this long, winding journey, let me briefly retrace the history of the Losheng Sanatorium as well as the Losheng Preservation Movement.

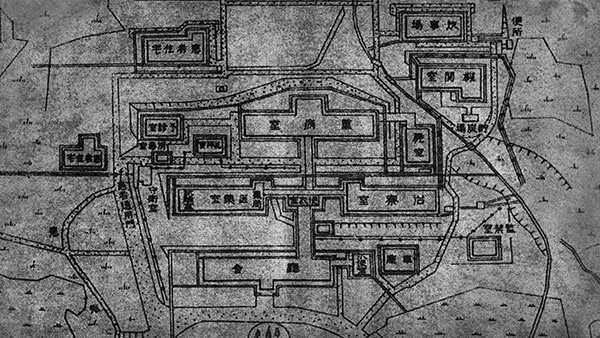

Blueprint drawing of Losheng Sanatorium, 1930.

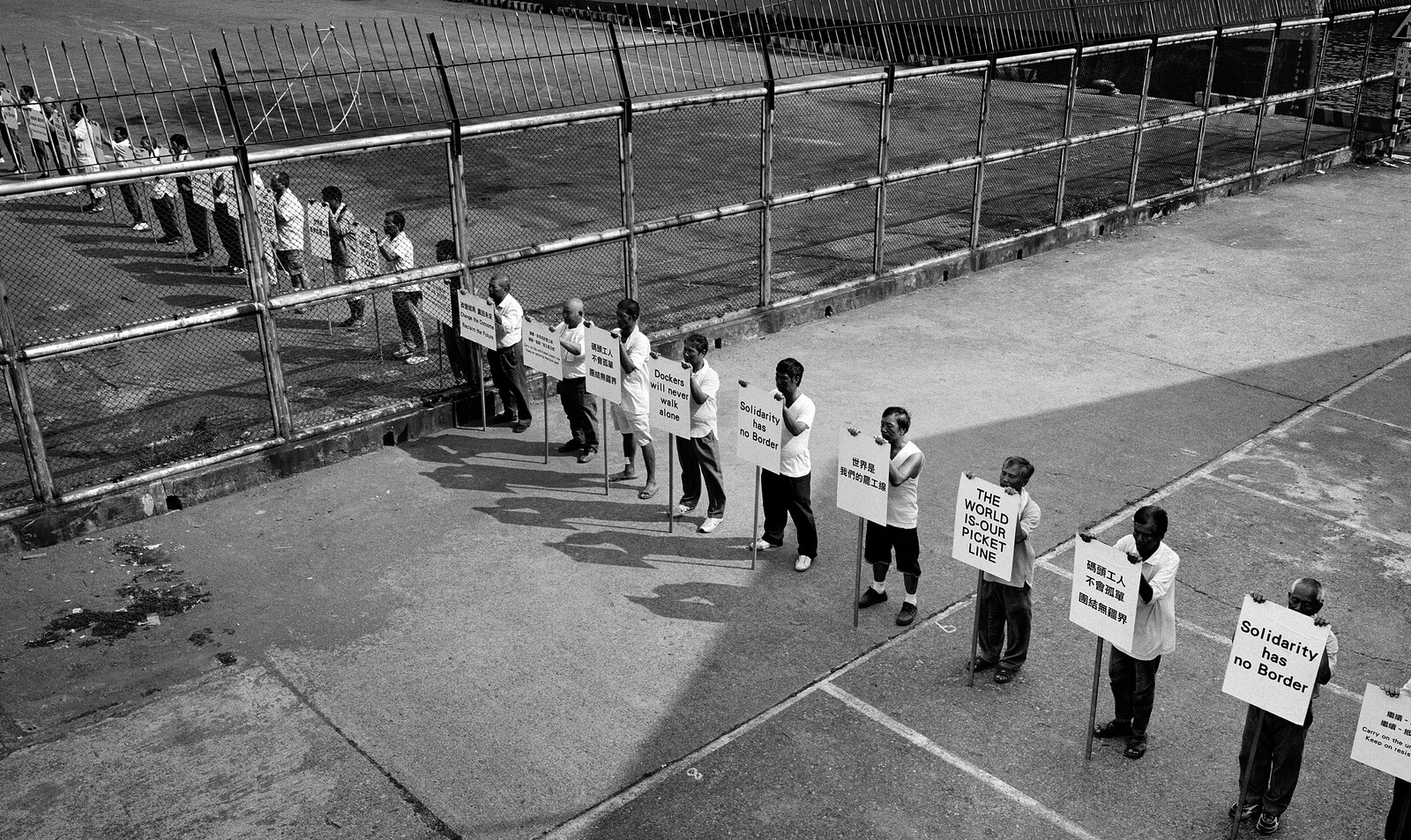

Losheng Preservation Movement, on the morning of December 3, 2008. Photo: Chang Li-ben

A History of the Losheng Sanatorium and the Losheng Preservation Movement

At the beginning of the Meiji Restoration, in an effort to catch up with Europe and the US as well as to “enrich the state, strengthen the military” (fukoku kyōhei), and build a “civilized” state, Japan regarded pandemics and leprosy as a “national disgrace,” indicative of a barbaric and backwards country.1 In 1907, the Home Ministry (Naimu-shō) issued a law entitled “Matter Concerning the Prevention of Leprosy,” which aimed to forcibly isolate all Hansen’s Disease patients by establishing sanatoriums in which to house them.

In 1926, thirty-one years into Japan’s colonization of Taiwan, the Japanese government decided to implement the same public policy in its colonies. This decision was intended both to prevent the Japanese population in Taiwan from contracting leprosy—in accordance with Japan’s eugenic aspirations—and to maximize local labor efficiency, ensuring the continuing growth of Japan’s economic power.

That same year, Mannoshin Kamiyama, the Governor-General of Taiwan—the head of Japan’s colonial government on the island—made the decision to build a leprosy sanatorium in the country. In 1930, the Rakusei (Losheng) Sanatorium was completed in the foothills of Danfeng Mountain, in the Xinzhuang district of Taipei. Thus began the forced isolation of local Japanese and Taiwanese leprosy patients, who were sterilized and forbidden to marry. Wire fences enclosed the sanatorium to prevent escape.

In 1945, after World War II, the Kuomintang government succeeded the Japanese colonial regime, and the Rakusei (Losheng) Sanatorium for Lepers of the Governor-General of Taiwan was renamed the Losheng Sanatorium of the Taiwanese Provincial Government. The Kuomintang largely carried forward colonial Japan’s practice of forcibly isolating leprosy patients, but this changed after the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950 and the onset of the Cold War, when the US began to intervene in and dominate Taiwanese political, economic, military, and public health policy.

The US funded an expansion of the Losheng Sanatorium in order to house leprosy patients from the Kuomintang army and from the population at large, with the aim of ensuring a healthy Taiwanese military and labor force for the anticommunist effort. From the 1940s through the ‘60s, the US also gradually introduced biomedicines such as DDS (dapsone) into the sanatorium. Human medical experiments were conducted on the patients in order to test dosages and effectiveness.2 Unable to withstand the neuropathic pain caused by over-dosages, a great number of sanatorium residents ended up tragically committing suicide.

Subsequent advances in global knowledge about Hansen’s Disease led the Kuomintang to abolish the leprosy isolation policy in 1961. However, because the disease’s negative reputation had long been established and reinforced, most Hansen’s Disease patients faced tremendous difficulties reintegrating into society.

In 1994, Taiwanese bureaucrats and local political forces conspired to have the Xinzhuang metro depot moved to the Losheng Sanatorium site. In 1995, sanatorium residents who were initially forced to “adopt the sanatorium as their only home” learned that they were to be relocated. They organized petitions and protests to preserve their right to stay. In 2002, the first round of demolition at the Losheng Sanatorium provoked a backlash from the Hansen’s Disease patients and the general public, resulting in the creation of the Losheng Preservation Movement. In addition to the Youth Alliance for Losheng, organized by students in 2004, and the Losheng Self-Help Organization, organized by sanatorium residents in 2005, groups of scholars, lawyers, engineers, and cultural workers joined the movement. By the end of 2008, following the forced dispersal of the occupying protesters and residents, the Losheng Preservation Movement had waned, although the Losheng Self-Help Organization and the Youth Alliance for Losheng continued to protest against landslides and ground fractures caused by the construction of the new metro depot.

The Losheng Preservation Movement may have petered out, but at its height it stimulated various groups in Taiwanese society—through questions that emerged from the personal stories of patients and the history of Taiwanese public health policy—to investigate topics such as biological sovereignty, the meaning of “civilization,” the relationship between pandemics and colonial modernity, and the human body under medical and public welfare systems. New agendas and areas of study also arose, such as the human rights of leprosy patients, the cultural heritage of the sanatorium, the politics of public construction projects, and the conservation of soil and water. Countless essays and reports on these topics were published. In additon, the Losheng Preservation Movement gave rise to a range of creative projects, including documentaries, photojournalism, plays, and musical compositions.

Chen Chieh-jen, Realm of Reverberations: The Suspended Room, 2014.

The Winding Journey

In 2006, the Losheng Preservation Movement had taken a series of actions to petition for a delay of the planned demolition and to call for a preservation project to maintain 90 percent of the sanatorium. That same year, I was invited to participate in the Liverpool Biennial. The biennial curator hoped that participating artists would create works related to Liverpool—a city that had been going downhill since World War II, losing nearly 70 percent of its original population.

Because my knowledge of Liverpool was limited, a friend introduced me to a young Taiwanese student who would assist me with my field research about the city. Her name was Hu Ching-ya. She was a member of the Youth Alliance for Losheng and was already participating in the Losheng Preservation Movement.

We traveled to Liverpool four times and visited the Liverpool Longshoremen’s Union, which had organized a strike against the privatization of the Liverpool port 1995. The anti-privatization and anti-casualization movement ended in failure, but as Hu Ching-ya and I traveled back and forth between Taiwan and Liverpool, this movement and the Losheng Preservation Movement merged into one and the same cause in our discussions.

I thought the two seemingly distant and starkly different movements might in fact share a certain essential connection. Yet at the time, I was not able to articulate exactly what this connection might be.

I then made the short film The Route, based on my field research in Liverpool. In the film, I invited members of the Kaohsiung Longshoreman’s Union in Taiwan to cross over the fence between public areas and privatized wharfs, forming a fictional picket line. The film was my response to the Liverpool longshoremen’s anti-privatization movement, which took the Liverpool strike as a beginning that would later develop into a globally connected anti-privatization movement involving longshoremen from around the world.

Although this globally connected movement was not able to stop port privatization, it led me to ponder how to use artistic creation to imaginatively extend these seemingly failed attempts, so as to bring out inspirational and positive meanings that would then allow the viewer to imagine further continuations of these stories, experiences, and strategies.

In 2007, as the Losheng Preservation Movement was protesting the government’s rejection of the proposal from scholars to preserve 90 percent of the sanatorium, I received a commission from the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid. This was also the year when the Spanish Congress of Deputies passed the Historical Memory Law, written to formally condemn General Francisco Franco’s dictatorship (1936–75) and to offer compensation and aid to victims of the White Terror period, which extended from the Spanish Civil War through the end of Franco’s reign.

The commission provoked me think about Taiwan’s notorious Military Court and Prison. My childhood home was located opposite this facility, where political prisoners were imprisoned and tortured during Taiwan’s Martial Law period (1949–87). In 2002, the government of the Democratic Progressive Party listed it as a historic site and planned to transform it into the Jing-Mei Human Rights Memorial and Culture Park. This made me reflect on how, during the anticommunist Martial Law period, the state not only imprisoned dissidents, but also implemented rules and disciplinary programs throughout society to “surgically excise the minds” of average people. No longer exposed to the views of dissidents and critical thinkers, Taiwanese people gradually lost their imagination, values, and social agency. They were also shaped into docile low-wage factory workers and consumers pursuing consumerist desire. This was perhaps one of the reasons why, after the Martial Law period ended, Taiwan was able to transition smoothly to a neoliberal bourgeois democracy.

For my commission from the Reina Sofía I decided to construct a dialectical, fluctuating fictional field that mapped the spaces of the Military Court and Prison under Martial Law, the factories from the time when Taiwan was a world manufacturing center, and the to-be-inaugurated Jing-Mei Human Rights Memorial and Cultural Park. I also wanted to invite present-day activists, unemployed laborers, immigrant workers, and homeless people into this dialectical field. So I decided to have them come together at the Culture Park and engage in complex, nonverbal, fictional dialogues about what defines “equality” and “human rights.”

As I was seeking actors for this project, Hu Ching-ya introduced me to Chang Li-ben, also a member of the Youth Alliance. After in-depth conversations, I decided to cast him as a fictional political prisoner whose existence was suspended just before the day Martial Law was abolished, at 23:55:50. He cannot grow old, die, or ever leave the Military Court and Prison.

On December 10, 2007 (International Human Rights Day), as I was busy using found materials to build a fictional Military Court and Prison inside a corrugated metal building, on the actual site of the Military Court and Prison, a grand ceremony was held to inaugurate the Jing-Mei Human Rights Memorial and Cultural Park. Disguised as journalists, members of the Youth Alliance attended the ceremony to protest the Democratic Progressive Party government. The government was waving the flag of human rights while refusing to deal with the concurrent issue of the Hansen’s Disease patients being stripped of their human and residential rights.

During this protest, an astonishing thing happened: one of the family members of a White Terror victim slapped a protesting female student. This drove me to mull over the type of ideological apparatus that would condition the family member of a White Terror victim to react with literal violence to someone supporting the victims of another cause. In other words, after the historical transition in many parts of the world from autocratic dictatorship to neoliberal biopolitical governance, how do we think about human rights? How can we approach it in a way that not only connects it to histories like the White Terror period, but also deconstructs the biopolitical ideological apparatus that mediates our everyday life and identity?

After I completed the film Military Court and Prison, I was invited to the first New Orleans Biennial, which took place three years after Hurricane Katrina devastated the city in 2005. Wanting to further my previous field research on the reconstruction New Orleans, I applied for a US visa. Yet my research subject shifted to the unequal visa policies of Taiwan and the US, because my visa interviewer from the American Institute in Taiwan suspected that I intended to immigrate illegally. Then, on December 3, 2008, the police force forcibly dispersed the demonstrating sanatorium residents, students, and members of the general public.

Burnt Tree Roots, Indiscernible Images, Empty Chairs

In the few years that followed, I focused on expanding my research on the notion of uprooting imperialist ideologies.

It was not until 2012, during my year-long production of Happiness Building inside a factory complex near the Losheng Sanatorium, that I met Chang Fang-chi, the eventual lead actor in Keeping Company, the second part of my four-part film Realm of Reverberations. We came to know each other well, and I learned that she was introduced to the Losheng Preservation Movement by a friend when she was eighteen years old and studying philosophy in college. After the decline of the movement, Chang decided to remain at Losheng. Besides keeping the elderly residents company, she also created an abundance of personal documentation in the form of emotional writings, sketches, and graffiti. What felt curious to me was that she never became a member of the Youth Alliance and only wanted to be a companion to the sanatorium residents and the movement itself.

My first visit to what remained of the sanatorium came when injured crew members from Happiness Building were taken to the new hospital adjacent to the sanatorium. After visiting them at the hospital, I walked across the overpass above the metro depot construction site and into Losheng’s remains. This was six years after I first met Hu Ching-ya and began hearing about the Losheng Preservation Movement from her.

After this, and because of Chang Fang-chi, my younger brother and I would spend our spare time at Losheng, chatting with Chang and the residents.

In 2013, Chang, my brother, and I visited Losheng after a typhoon. We saw many trees that had been blown over, including a chaulmoogra tree lying next to a toppled banyan tree. Those who are familiar with Hansen’s Disease know that, before modern medicines such as DSS, chaulmoogra oil was one of the traditional treatments used (although according to clinical reports as well as sanatorium residents, its effectiveness is limited). Chang told us that this chaulmoogra tree was the last one remaining after 70 percent of the sanatorium had been demolished.

A few days later, when we went back for another visit, we saw groundkeepers sawing down the damaged trees. I asked why and they told me that officials from the Ministry of Culture had come for an inspection and decided that the trees might fall and injure people. As I witnessed the groundkeepers saw down these trees—planted by residents a few decades ago—and burn their roots, I had an indescribable feeling, fading in and out of the diffusing smoke. I subsequently visited the remnants of Losheng even more often, as if driven by this indescribable and unknowable feeling.

During one of our Losheng visits, we found several boxes of slides that were going to be thrown out. These were likely used in the 1970s and ’80s to display medical reports and images of the various stages of Hansen’s Disease. The slides in one box had chemically eroded due to humidity and the passage of time, becoming indiscernible abstract images. To me, the erosion of these slides—the transition from explanatory images to abstract images—gestured to the fact that we will never be able to truly comprehend the manifold physical and psychological pains Hansen Disease patients endured.

During those days when I visited Losheng frequently, I often saw chairs, once used by the residents, now abandoned in piles by the road, waiting to be discarded. I wondered, wasn’t the Ministry of Health and Welfare building a Losheng Culture Park? And weren’t these chairs, some of which bore scratch marks on the armrests left by the patients’ gnarled fingers, truthful records of their writhing, agonized bodies and the pains that we will never really comprehend or witness? When I looked at those chairs destined for the garbage heap, I felt that what was being discarded was not so much the chairs as, one after another, the residents we will never come to know.

One day at dusk, Chang and I stood outside the sanatorium’s Datun Dormitory, right by the fence surrounding the metro depot construction site. We looked at the site before us, where countless protests and self-organized events had taken place, as Chang told me about how the police had dispersed protesting residents and their allies at the end of 2008. The newly dug foundation for the metro depot had been the site of much of the sanatorium’s housing, now vanished. Industrial noises from the construction overlapped with Chang’s soft-spoken words, creating a symphony of disparate sounds. At that moment, Chang was no longer just an individual. She was, rather, a unity of all the residents and activists whose company she once kept.

As the daylight dwindled, a resident with whom Chang wasn’t acquainted came and sat inside a shabby alcove nearby, silently watching the construction site. When I walked over and tried to chat with him, he looked up at me with a smile and said repeatedly: “I’m ninety years old, neither of my ears can hear anymore, not anymore …”

And so the three of us looked at the construction site silently, as the migrant construction workers continued working into the night and the skyscrapers in the distance gradually lit up. Although we were all looking out at the same construction site, our thoughts were likely very different. What was the ninety-year-old resident thinking about? His forced isolation years earlier, after his Hansen Disease symptoms began to show? Or perhaps his youth before he became ill? What was Chang thinking about? Those unending nights as a Losheng Patrol Team member during the height of the protests? Was she thinking about Uncle Yang, a resident who she was friends with for a long time until he passed away? Or was she perhaps thinking about the idea that she and her friends had developed for an alternative Losheng Museum, but that now seemed impossible to realize?

And how about myself? It was impossible for me to comprehend their life experiences. I could only look out on the gigantic construction site and imagine how, to the noncitizen migrant workers, the construction site and its enclosing metal fence might be a New Losheng Sanatorium.

A Fluid Museum, an Ineffable State

After that night, I began to think: if I, who was not present to take part in the Losheng Preservation Movement, hadn’t met Hu Ching-ya, Chang Li-ben, and Chang Fang-chi, I may never have come to visit the remnants of Losheng or to have these thoughts. Was it possible for me, a “latecomer” who had never seen the sanatorium before its demolition, to ever come to know the sanatorium’s complex history in full?

But perhaps, like the roots of the more than eight hundred trees that residents had planted inside the sanatorium, the Losheng Preservation Movement had expanded into a massive and complex movement not confined to a single time, place, or meaning. In other words, perhaps Losheng had been a site of manifold meanings from the very beginning.

A few days later I met with Hu Ching-ya and Chang Fang-chi to ask them about the alternative Losheng Museum project. What else did they imagine would be included besides a history of the sanatorium, the personal histories of the residents, and the clinical history Hansen’s Disease itself? Although they each had different answers, there was one shared wish: that the museum be a fluid museum, one that would start with the Losheng Sanatorium but then expand out to interconnect other groups of people similarly excluded by state policies.

As I listened to their ideas, I wondered: Aren’t we all “latecomers” in one way or another? We are always situated at the before or after, on the outside or inside of any given event, and therefore we are always witnessing only certain tiny fragments of this world. Yet those who “came after” are given the opportunity to rearrange, collage, and piece together all these fragments, allowing alternative narrations as well as an alternative social vision.

I then began conceptualizing the film project Realm of Reverberations. The finished work involved four separate videos, assuming the perspectives of four different protagonists: Tree Planters was told from the perspective of Chou Fu-tzu, chairman of the Losheng Self-Help Organization; Keeping Company was told from the perspective of Chang Fang-chi, who has kept long-term company with the sanatorium residents until this day; The Suspended Room was told from the perspective of Liu Yue-ying, a woman from mainland Chinese who lived through the Cultural Revolution and worked as a caretaker at the sanatorium; and Tracing Forward was told from the perspective of a fictional female political prisoner, played by Hsu Yi-ting, who travels through Taiwanese history, from the Japanese colonial period to the present, to discuss whether the “conclusion” of an “event” is equivalent to its “ending.”

In the videos, I used very little spoken or textual content to relate the history of the sanatorium and the preservation movement. Instead, the videos were primarily dedicated to fragments—of the sanatorium scenery, of the ruins of the complex, of the “indefinable” people found there, and of other inexplicable objects and sounds associated with the place. I have a stubborn and perhaps single-minded belief that art in our post-internet era need not provide easily researchable knowledge or narratives. Rather, art today should be concerned with producing “ineffable images” or a kind of “ineffable state” that cannot easily be absorbed into social spectacles or biopolitical regimes.

Three Generations of Colonial Modernity and the New Losheng Sanatorium

After I completed Realm of Reverberations, the Losheng Sanatorium took on a more complex meaning for me. Rather than just a highly regulated space that forcibly housed and sterilized Hansen’s Disease patients, it became a place of broken fragments shaped by multiple, intertwining long-term conflicts, much like the Taiwanese people have been shaped by three generations of colonial modernity and its ruling ideology.

Although history cannot be easily dividing up into chronological sections, I will nonetheless employ that method here for the express purpose of destroying it.

The first generation of colonial modernity in Taiwan was the period from 1895 through 1945, when Japan attempted to colonize all of Asia. Japan sought to clean up and oppress the “unwashed” and “disobedient” people under its rule, both in its colonies and domestically. It formulated three principles of colonial governance in Taiwan: Japanization (Kōmika), industrialization, and the transformation of Taiwan into a base for further Japanese expansion southward. Japan implemented these policies in the guise of education reform. It also introduced into Taiwan and its other colonies the idea of a “standard of civilization.”3

The second period of colonial modernity, from 1950 through 1987, was the Martial Law period, when Taiwan positioned itself on the US side of the Cold War anticommunist divide. The US supported the anticommunist, monarchical Kuomintang regime, ferociously suppressing anyone in Taiwan with alternative political visions. Via the “cultural Cold War,” the US also introduced bourgeois democratic values such as “freedom” and “democracy” into Taiwan’s education, media, and pop-cultural systems, replacing the feudal values of Japanization. The human medical experiments conducted on Losheng residents from 1950 to 1965 under the US’s public health plan for Taiwan (including those experiments unrelated to healing Hansen’s Disease) could perhaps be read as visible manifestations of second-generation colonial modernity and a new standard of civilization imposed on Taiwanese people by the US. In other words, as Hansen’s Disease patients underwent medical experiments, the Taiwanese people were simultaneously undergoing another kind of “human experiment” aimed at reforming their thoughts and feelings.

Under US pressure, in 1984 the Kuomintang government announced plans to implement neoliberal economic reforms. The reforms were carried forward by the Democratic Progressive Party, which came to power after the end of the Martial Law period, setting the stage for the third era of colonial modernity in Taiwan, which has stretched from 1987 until the present. Early in this period, neoliberal policies resulted in lots of factories in the relatively less developed Xinzhuang district of Taipei (where the Losheng Sanatorium is located) moving offshore. In 1994, Taiwanese officials proposed building a new metro depot on the site of the sanatorium, pitching it to the local residents as a form of much-needed economic development. This helped rally forty to fifty thousand local Xinzhuang residents to oppose the aims of the Losheng Preservation Movement. Here the ruling class used the “democratic” strategy of dividing and conquering the people. They pitted groups against each other in order to confine the process of discussion—a fundamental principle of direct democracy—within representative democracy and ballot calculations.

One core aim characterizes all three generations of colonial modernization in Taiwan: the extinction of the communist imagination.

The cultural Cold War employed a “left on left” policy to successfully suppress any stirrings of the communist imagination in capitalist nations.4 Are we not now engaged in a new Cold War in which governments like the US and transnational bodies like the International Monetary Fund and World Trade Organization use neocolonial tactics to intentionally confuse the distinction between left-wing and right-wing ideologies?5 This approach involves pushing neoliberal privatization while simultaneously permitting a certain amount of seemingly left-wing speech and activism. It takes movements that target neoliberalism on a global scale and tries to shift their focus to regional and local oppressions resulting from neoliberal policies. As a result, people impoverished by neoliberalism place the blame for economic inequality on simplistic and delusional scapegoats such as labor unions, or even on people with alternative political imaginations, such as those who advance a communist vision of the future.

In East Asia, under the current Worker Dispatch Law and the overall push for labor flexibilization, an increasing number of people are forced to become exiles in their own land—“dispatched workers,” or temporary laborers without a stable income. The first country in East Asia to establish a Worker Dispatch Law was Japan, in 1985.6 In the twenty years since, 19.9 million Japanese people have became dispatched workers. Though Taiwan hasn’t formally established its own Worker Dispatch Law, policies intended to make work more flexible are concealed within various regulations and unspoken rules about “atypical employment.”

Are these dispatched workers not the new colonized slaves of bourgeois democracy and its internal colonialism? When empires that disseminate neoliberalism also try to guide people around the world in how to take action, while intentionally blurring the tremendous class disparity that separates citizen from citizen, is this not a “New Losheng Sanatorium,” one that uses labor flexibilization to implement an alternative form of exclusion under the guise of “freedom” and “democracy”? Now, however, the isolated and excluded are no longer just leprosy patients; they are everyday people forced to live in a neoliberal society.

When we ponder the centuries-old question of what makes a more equal human society, we should not only think about secure and well-paid employment for dispatch workers and other precarious members of society. We should also think about the need to allow for the emergence and practice of alternative social visions. And we should understand that bourgeois democracy, which is in fact a new global colonialism, is a major obstacle to realizing such visions.

In addition, we should understand that when we talk about art, we are also reflecting upon how our thoughts and feelings came to be mediated and constructed.

We need to pull back the curtains that enclose us on all sides, to reexamine the cities we live in. Are the cities we call home really just New Losheng Sanatoriums? Are we complicit in the construction of these sanatoriums? Are we the forcibly isolated?

This brief history derives mainly from the unpublished A Record of Critical Events at the Losheng (2009) by Hu Ching-ya, as well as Fann Yen-chiou, Epidemic, Medicine and Colonial Modernity: The Medical History of Taiwan under Japanese Colonial Rule (Daw Shiang Publishing, 2005).

Because Mycobacterium leprae cannot be cultivated outside the human body, academics still debate whether the experiments on Losheng residents using medications such as DDS can be deemed “human medical experiments.” However, during the USAID period in Taiwan, a “cellular immunity mechanism” project conducted on the leprosy patients likely faced unwillingness and disobedience on the part of the patients. For related research, see Fann Yen-chiou, “USAID Medicine, Hansen’s Disease Control Policy, and Patients’ Rights in Taiwan (1945–1960s),” Taiwan Historical Research, vol. 16, no. 4 (2010): 115–60.

On Japan’s national structure (Kokutai) since the Meiji Restoration, see Tsurumi Shunsuke, An Intellectual History of Wartime Japan, 1931–1945 (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten Publishers, 1982). The Chinese translation of this book was published by Flâneur Culture Lab. Regarding the “standard of civilization” and related subjects, see Origins of Global Order: From the Meridian Lines to the Standard of Civilization, ed. Lydia Liu (Beijing: Joint Publishing, 2016).

See Frances Stonor Saunders, Who Paid the Piper? CIA and the Cultural Cold War (London: Granta Books, 2000).

The US PRISM project discussed in the documents leaked by Edward Snowden, along with other programs mentioned in documents uncovered by the recent hack of George Soros’s Open Society Foundations, demonstrate how the US and multinational capitalists interfere with “civic” movements around the world.

Japan passed its Worker Dispatch Law in 1985, implemented it in 1986, and amended it five times.

Category

Subject

All images are courtesy of the artist.