See Jamie Linton and Jessica Budds’s concept of the hydro-social. Linton, Jamie, and Jessica Budds, “The Hydrosocial Cycle: Defining and Mobilizing a Relational-Dialectical Approach to Water,” Geoforum, 57 (2014) 170-180.

Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics, trans. Steven Corcoran (Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2019), 92. Italics in the original.

Ifor Duncan, “Hydrology of the Powerless.” Doctoral thesis, Goldsmiths, University of London (2021). See ➝.

Jamie Linton has called this modern water through his reading of Horton’s hydrologic cycle alongside the inception of the chemical formula H2O. Jamie Linton, What is Water: The History of a Modern Abstraction (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2010), 224. Jeremy Schmidt has elsewhere drawn on what he calls the production of “normal” water not so much as a product of modernity as Linton suggest, but as co-constitutive with it. Instead, he formulates normal water around the liberal project. Jeremy Schmidt, Water: Abundance, Scarcity, and Security in the Age of Humanity (New York: New York University Press, 2017).

Robert E. Horton, “The Field, Scope, And Status of The Science of Hydrology,” Transactions of the American Geophysical Union (1931), 190-1.

Linton, What is Water.

Richard White, The Organic Machine: The Remaking of the Columbia River (New York: Hill and Wang, 1995). Philip V. Scarpino, “The Organic Machine: The Remaking of the Columbia River,” Technology and Culture 40:2 (1996), 419-420.

Water has strategic importance in Russia’s invasion. After its annexation of Crimea in 2014, Ukraine blocked the North Crimean canal that diverted water from the Dnipro to irrigate rice fields in the peninsula. Since its 2022 invasion Russia has been able to reopen the canal. Jason Beaubien, “Russia has achieved at least 1 of its war goals: return Ukraine”s water to Crimea,” NPR, June 13, 2022. See ➝.

The work of Astrida Neimanis is influential here: Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology (London: Bloomsbury, 2017).

See Cecelia Chen; Janine MacLeod; & Astrida Neimanis, (eds.), Thinking With Water (Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 2013) as well as GIDEST, Anuradha Mathur and Dilip da Cunha - Wetness Everywhere. August 7, 2017. See ➝.

Derek Gregory, “(Post)Colonialism and the Production of Nature,” in Noel Castree ed., Social Nature: Theory, Practice and Politics (Malden MA: Blackwell, 2001) 84-111, 97; Vandana Shiva, Monocultures of the Mind, (London: Zed Books, 1993), 2.

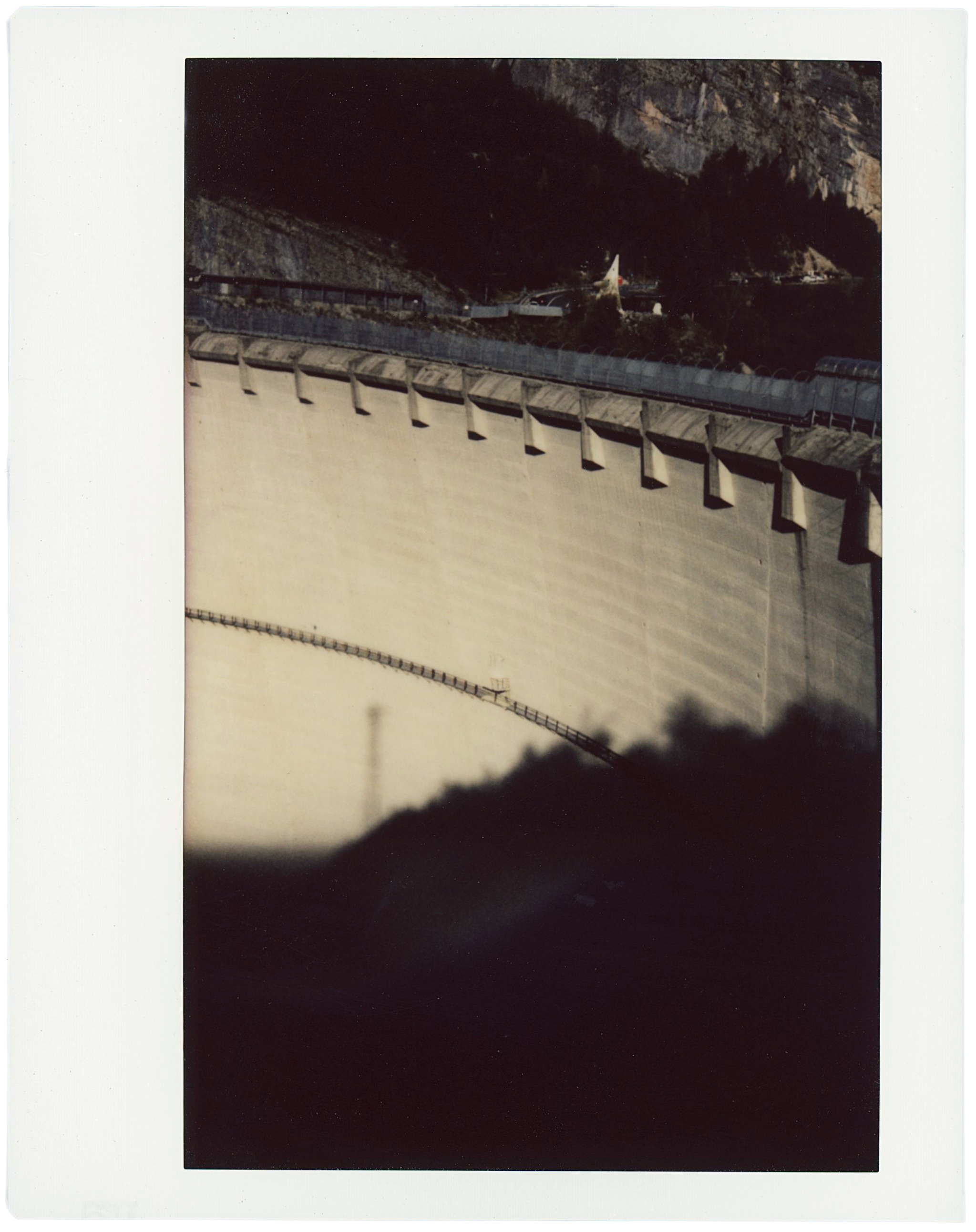

For now, the dam is the last of its scale to be built in Colombia with popular opinion turning against major infrastructure projects that have been embroiled in corruption and fraught with ecological devastation.

EPM are a subsidiary company of the Medellín Mayoral government. Directors of Hidroituango have been investigated for not properly insuring the dam.

The Centre for International Environmental Law (CIEL), claim that the dam will have an impact on 180,000 people, with an estimated 700 families already being displaced. CIEL, 18 May, 2018, “Comment on Movimiento Ríos Vivos Antioquia”s Activism Regarding Hidroituango.”

Perpetrated by paramilitary groups with state collusion: Ituango Massacres v. Colombia, Inter-American Court of Human Rights (July 1 2006). See ➝.

Mariana Calvo, “How paramilitaries laid the foundation for Colombia”s largest hydroelectric dam,” Colombia Reports, March 2, 2020. See ➝.

Movimiento Ríos Vivos Colombia, “La vida está en riesgo con Hidroituango,” November 5, 2022. See ➝.

In March 2019, the Jurisdicción Especial Para la Paz (JEP), the body set up as part of the peace agreement between the Colombian Government and FARC to administer transitional justice in 2016, opened proceedings directed towards EPM, and the Governor of Antioquia regarding access to sites where the bodies of victims might be found (including Ituango). Jurisdicción Especial Para la Paz (JEP), “Avanzan actuaciones por solicitud de medidas cautelares de 16 lugares donde habría fosas con personas desaparecidas,” March 6, 2019. See ➝.

Fiscalía General de la Nación – Colombia, “‘¡Viva el Cauca!‘: la segunda fuente hídrica más importante del país,” YouTube (April 10, 2019), ➝.

The submerged recording is reminiscent of a scene in artist Carolina Caycedo”s film Yuma, or the Land of friends (2014) where she submerges her camera into the turbid waters of the Magdalena river. Macarena Gómez-Barris equates Caycedo”s appreciation of the visual and sonic spaces within the river to the production of an “anti-dam counter-logics” and “submerged perspective.” For the “subtlety and complexity” that hydropower tries to erase see Macarena Gómez-Barris”s conception of the extractive gaze and submerged perspectives. The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives (Duke University Press, 2017).

Linton (2010), 18.; Derek Gregory (2001), 97.; Dilip Da Cunha, The Invention of Rivers: Alexander”s Eye and Ganga”s Descent (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018), 12.; Vandana Shiva (1993), 2.

Hannah Meszaros Martin & Oscar Pedraza, “Extinction in transition: coca, coal, and the production of enmity in Colombia”s post-peace accords environment,” Political Ecology 28 (2021): 721-740, 723.

Ifor Duncan and Stefanos Levidis, “Weaponizing a River,” e-flux Architecture, 2020. See ➝.

Acknowledgements: I am grateful to my guide Professor Francesco Vallerani, the attentive reading of Nick Axel, Hannah Meszaros Martin, Oscar Pedraza, Nile Davies, Daniel Mann, Stefanos Levidis, and the artist Carolina Caycedo with whom I had a conversation many years ago about Hidroituango