July 16–August 17, 2013

Despite the possession of a rich literary pedigree, the good old chicken-or-egg quandary of fact or fiction seems to receive limited play if not in the Latin American context, then the Mexican context of contemporary art (and by literary, I mean of course Julio Cortázar, and even more importantly, Jorge Luis Borges, who reveled in this mental stew regularly). Why is this? Well, beyond its origins in the critical re-evaluation of the promises of modernism, the theme seems to be the banal luxury of more politically stable climes, more at home in, say, Western Europe than in a region awash with unprecedented drug cartel violence and the albatross of responsibility that attends it. Given these conditions, such literary antics are liable to come off as politically irresponsible, all but rendering such ontological speculation a blithe, bohemian enterprise.

This charming group exhibition, curated by Fabiola Iza, manages to both sidestep and problematize such conceivable, context-specific political incorrectness by offering what could be perceived as a more nuanced perspective on said quandary. Entitled “A Trip to the Moon,” the show is positioned in-between two moments—the 1969 landing of Apollo 11 on the moon, a historic feat apparently riddled with doubt, and Georges Méliès’s feature film Le voyage dans la lune (1902)—in which fact and fiction purportedly dovetail to mutually aggravating and affirmative effect. These issues manifest here through a series of works that continually challenge beliefs and assumptions, obliging the viewer to wonder to what extent a given work might be the stuff of fact or fiction—an obligation that runs from the merely fanciful to the politically perplexing. Among the former group is French artist Laurent Grasso’s video animation, Psychokinesis (2008), of a boulder floating a desert landscape (think spoon-bending), which also happens to be one of the more tenuous examples, by virtue of being so obviously a digital animation and therefore arrantly unbelievable. Plausibility is entirely eschewed, however, in favor of the shamelessly ludic in Ulla von Brandenburg’s black-and-white film, Ein Zaubertrickfilm (2002), which depicts friends engaging in barroom-style magic tricks.

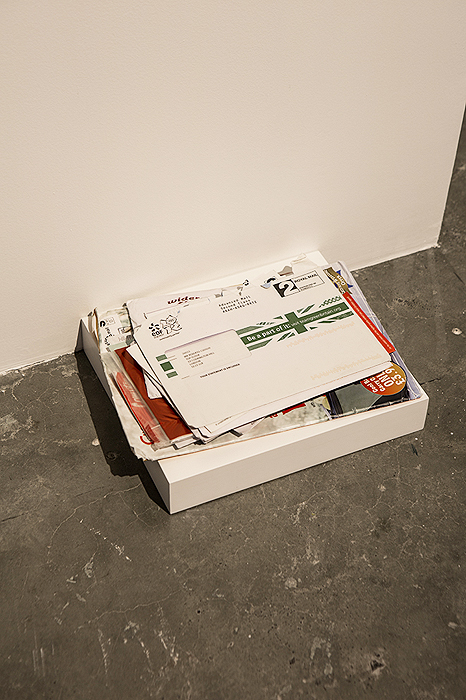

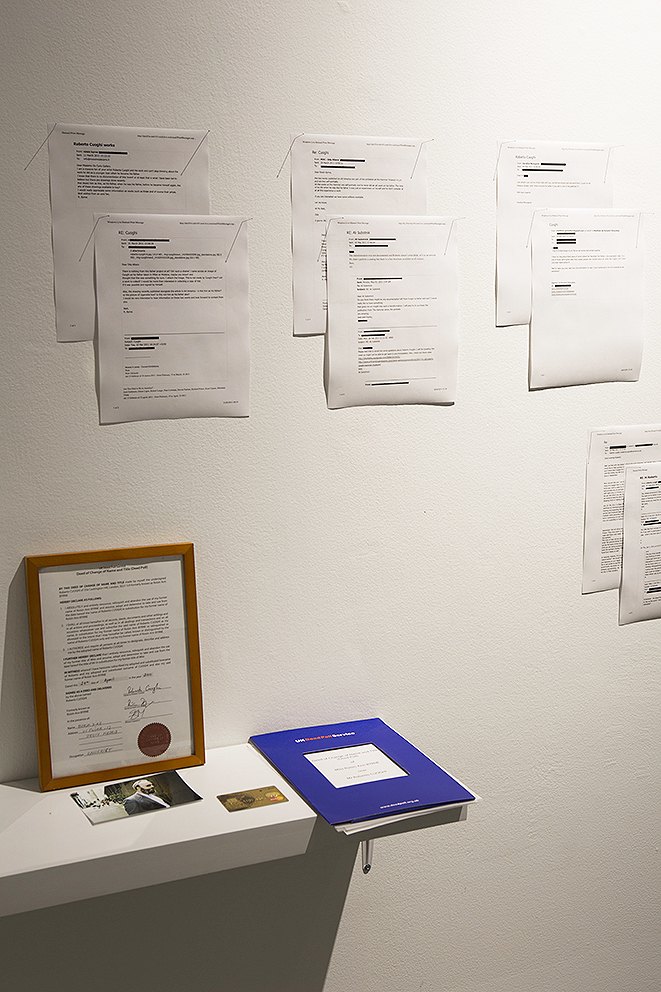

The curatorial proposition gains traction with works by Tania Pérez Córdova, Roisin Byrne, and Trevor Paglen. Pérez Córdova presents an elegant piece of fabric hanging on a wall, How to use reverse psychology with pictures (2012–13). According to the artist, this now-white fabric was once black; it was subjected to an artificial aging process in a specially designed laboratory and transformed to its current hoary state—a process that allegorizes technology’s paradoxical capacity to destroy as much as it might seek to preserve. Byrne’s contribution, entitled It’s not you, It’s me (2010–2011), consists of an elaborate hoax in which she legally appropriated the notoriously elusive Italian artist Roberto Cuoghi’s identity, which is here documented through email correspondence and objects such as a credit card in his name and mail addressed to him, which she received, as him: the hard fact of identity passed around and shared like so much camp-fire story fodder. It is, however, Paglen’s contributions that best problematize, not to mention, politicize the above-bandied about chicken/egg question in this context. One photo, Untitled (Predator Drones) (2011), shows a misty white skyscape in which a group of drones supposedly lurk (I could only make out one), while another photo, PARCAE 2-1 (A) in Monoceros (Naval Ocean Surveillance System; 1990-050A) (2013), depicts a blurry, long-exposure shot of a starscape in which a US spy satellite has supposedly been identified by the artist. Of course, not exactly fictions, what is portrayed in these photos participates in the ethos of conspiracy theory while conceivably preferring to remain enshrouded in the ether, as it were, of fiction, which is to say, supposedly not at all. Such willful nebulousness paradoxically points toward art’s capacity to both reveal and politicize that fine line between fact and fiction, while throwing if not a different, then at least a more complex light on questions of responsibility.