March 10–June 12, 2017

Bottles of seawater sit among makeshift red flags on charred concrete breezeblocks. “It’s like a fire,” says the artist, Dineo Seshee Bopape, of her installation, +/– 1791 (monument to the haitian revolution 1791) (2017), which is scattered about the courtyard of one of Sharjah Art Foundation’s warren of spaces. Small black lumps, formed by molding wet clay in the artist’s fist, are arranged in neat rows; piles of herbs are scattered about. The centerpiece of the courtyard—the fire-like construction—refers to the idea that the Haitian Revolution was brought on by the curse of a Voodoo priestess; the water, herbs, circles and votives elsewhere call on other faith systems of Africa and the African diaspora. Seawater is often said to have healing properties, while fuel can “release the spirit from bondage,” as Bopape puts it. The work is a depiction, and perhaps a performance, of spiritual opposition.

Indigenous belief systems, cybernetics, herbal remedies, Sufi meditations, and proto-monetary methods of exchange abound in Christine Tohmé’s Sharjah Biennial 13, titled “Tamawuj,” an Arabic word meaning a swelling or a rise. The exhibition is laid out across the Sharjah Art Foundation spaces in the center of Sharjah, in a few locations refurbished by the foundation (including their spiffy new studio spaces about 40 minutes’ drive north of the city), and in a variety of projects and conferences outside the run of the biennial, held throughout the year in Dakar, Istanbul, Ramallah, and the curator’s home city of Beirut.

This is Tohmé’s first major biennial; she is known best for her work as the head of Ashkal Alwan, the exhibition and discursive space in Beirut that has been such an important force for critical contemporary art within the region. At last year’s March Meeting—the yearly talks and performance event held by Sharjah Art Foundation—Tohmé gave a rousing speech on the crisis of contemporary art, but also on the failure on the part of critical art communities to make any kind of serious dent in neoliberalism and art’s participation in it. Art programs, she memorably declared, have simply become “redundant models for fundraising.”

Since then, the expectations for her Sharjah biennial have been high. On the first morning of the exhibition, which coincided with this year’s March Meeting, the space packed beyond its capacity. The subject under discussion, however—the potential and limitations of small-scale institutions—seemed far removed from the poetic register singled by the lyrical title of the biennial. The works on show, too, seemed less interested in addressing institutional critique than the biennial’s stated themes of “water, crops, earth and the culinary.”

The second day of the March Meeting deepened the apparent mismatch between the discursive claims of the organizers and the works themselves: Tohmé, accompanied onstage by research collaborators Lara Khaldi and Zeynep Öz and biennial artist Kader Attia, testified again to the crises of Trumpism, Brexit, nationalism, surveillance, and the crackdown on spaces, mobility, and intellectual freedom in the Middle East. Tohmé was fired up, and the crowd ate it up; but many were left wondering how to bridge these politics with the aesthetically resolved arguments beyond the lecture theatre—the abiding question of critical art practice.

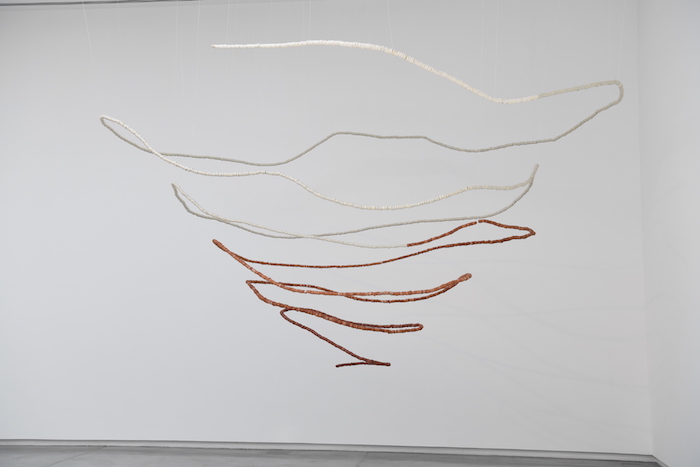

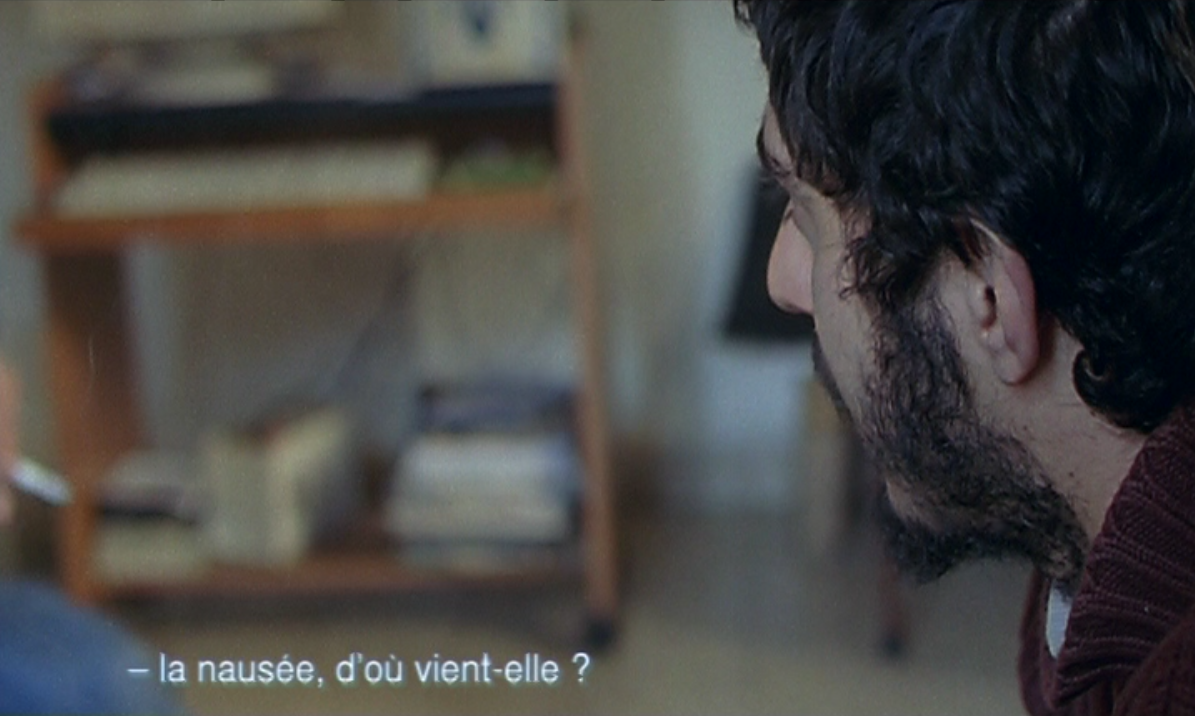

Then it came into focus. This is a biennial about the infrastructure of the art world and, yes, about the need for small-to-medium scale institutions as spaces for critique. Tohmé marries this institutional analysis to the show’s focus on counter-hegemonic systems of knowledge—Bopape’s Voodoo practices—that have been developed either by indigenous, colonized or oppressed people, or which oppose current secular scientific understanding. Uriel Orlow’s video installation The Crown Against Mafavuke (2016) tells the story of a medicinal healer in 1940s South Africa who was taken to court after a pharmaceutical company worried that its white customers were beginning to use his herbal remedies, and wanted to revoke his right to administer them. Taloi Havini looks at the indigenous form of shell money on Buka Island in Papua New Guinea, whose use was forbidden to white people under the colonial government. Her sculpture Beroana (shell money) (2015/17) displays laboriously made replicas of the shell in a winding fragile spiral. Raqs Media Collective gave a meditative, swirling performance about the possibility of cultural life on other planets (The Necessity of Infinity, 2017), drawing on Sufism to oppose Aristotelian thought.

Infinity was also the subject of Arjuna Neuman and Shahira Issa’s lecture-performance Rogue Planet (2017), which imagined bacteria as the real soul in our guts, and the means by which we might overcome mortality. Ursula Biemann and Paulo Tavares’s Forest Law (2014) showed in a set of video installations and archive material how the struggles over land and water rights in Ecuador are a front for the power struggles and racism of colonizing powers; their work details how the Sarayaku people won a court case recognizing that the forest itself has rights. Allora and Calzadilla’s video installation The Great Silence (2014) was also included, speculating on intelligence among parrots, and, seen from the point of the view of the birds, lamenting the loss of their language and traditions as their habitat is destroyed.1 Carefully and convincingly, Tohmé suggests connections between the roles that critical art institutions play, both within the landscape of contemporary art and in relation to these alternative belief systems.

This line of argument is an ethnographic one: it focuses on cultural lifeforms as preserved in communities of people, and thus challenges the role of critical discourse in delimiting art’s legitimate sphere of engagement. The art world fulfills the structural role of religion: a mode of thought and action, subscribed to by a global faithful and regularly attested to at festival events, with their rituals of dinners, bus conversations, and partial-video-watching. Tohmé talks about the art world in terms of infrastructure, which carries fewer troubled colonial associations than ethnography; it is also worth noting that art language is more at ease looking at the structures of the art world than the people who comprise them. But the biennial’s works, in their allusions to other forms of belief, point the other way, and their and Tohmé’s success here is to posit the art world as a “people.” Particularly in an Arab context, art’s critical counter-discourse is a powerful form of resistance to forces that actually work as agents of control and oppression.(2) Thinking of the art world as an underground belief system is a vote of confidence in contemporary art practice, framing its power as real rather than discursive.

Opposition is also seen as a performance, or something owed its aesthetic commemoration. These amount, I gather, to “Tamawuj,” the swelling of the biennial’s title. I have slight trouble with the show’s reliance on metaphor, particularly within a curatorial thesis that was only hazily sketched out and deliberately dispersed over time, site, and authorship. It was a relief to see a large-scale biennial treating global weirding, water rights, and crop disturbance, as in the Climavore lunch that London-based duo Cooking Sections (Daniel Fernández Pascual and Alon Schwabe) cooked for biennial guests from leaves and crops that grow in times of drought. But, as one artist noted, there’s a problem with treating climate change as a metaphor. It’s already the end of the world as we know it—what further, greater meaning could it possibly defer thought onto?

Some of the best works in “Tamawuj” elude the organizing heuristic altogether. İnci Eviner’s wild elaborations on the fixed position of women in her video and video installations Beuys Underground (2017) and Runaway Girls (2015) is one example; Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s Saydnaya (the missing 19db) (2017), the stand-out of the biennial, is another. The video installation analyzes how political prisoners in Syria’s Saydnaya prison, where speaking aloud is punishable by death, transformed their sense of hearing. They relied on sound to “see,” as it were, but lost their ability to speak: their tongues twisted when they tried to talk at a normal decibel level after their release. Saydnaya (the missing 19db) is part of Abu Hamdan’s project to create “earwitness” testimonies, by which the crimes that occurred in the prison may be brought to public understanding. It is a fitting work for a biennial that celebrates art’s capacity to challenge power.

(2)This thesis resonates in the Middle East, where curators and arts organisations regularly battle authorities for approval for exhibitions or to secure entry permits for visiting artists. Lebanon denied Tohmé her passport application in 2016, part of crackdowns on the cultural sector following anti-government protests, and a number of artists have recently been prohibited from entering the United Arab Emirates because of their work with the Gulf Labor Coalition.

The original script for the video, written by Ted Chiang in collaboration with the artists, was published at Supercommunity on May 8, 2015 and can be found at http://supercommunity.e-flux.com/texts/the-great-silence/.