After the completion of The Dinner Party (1974–89), for a five-year period from 1982 to 1987, Judy Chicago interrupted her study of female subjecthood to focus instead on its political other, masculinity. The result is a series of paintings and bronzes titled “PowerPlay,” a selection of which is currently on view at New York’s Salon 94. It’s affixed with the subtitle “A Prediction.” Of what?

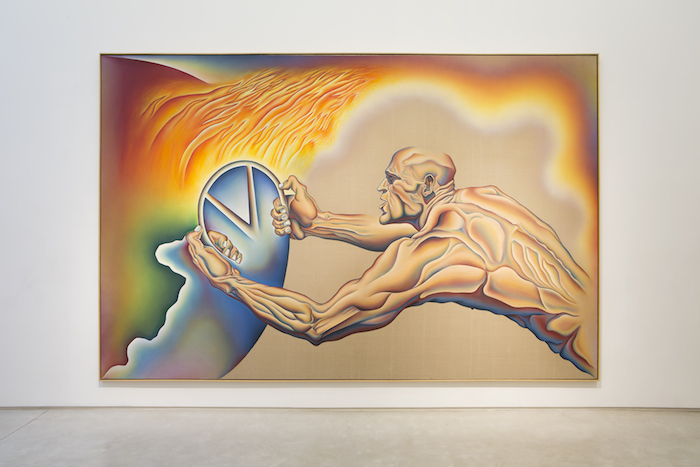

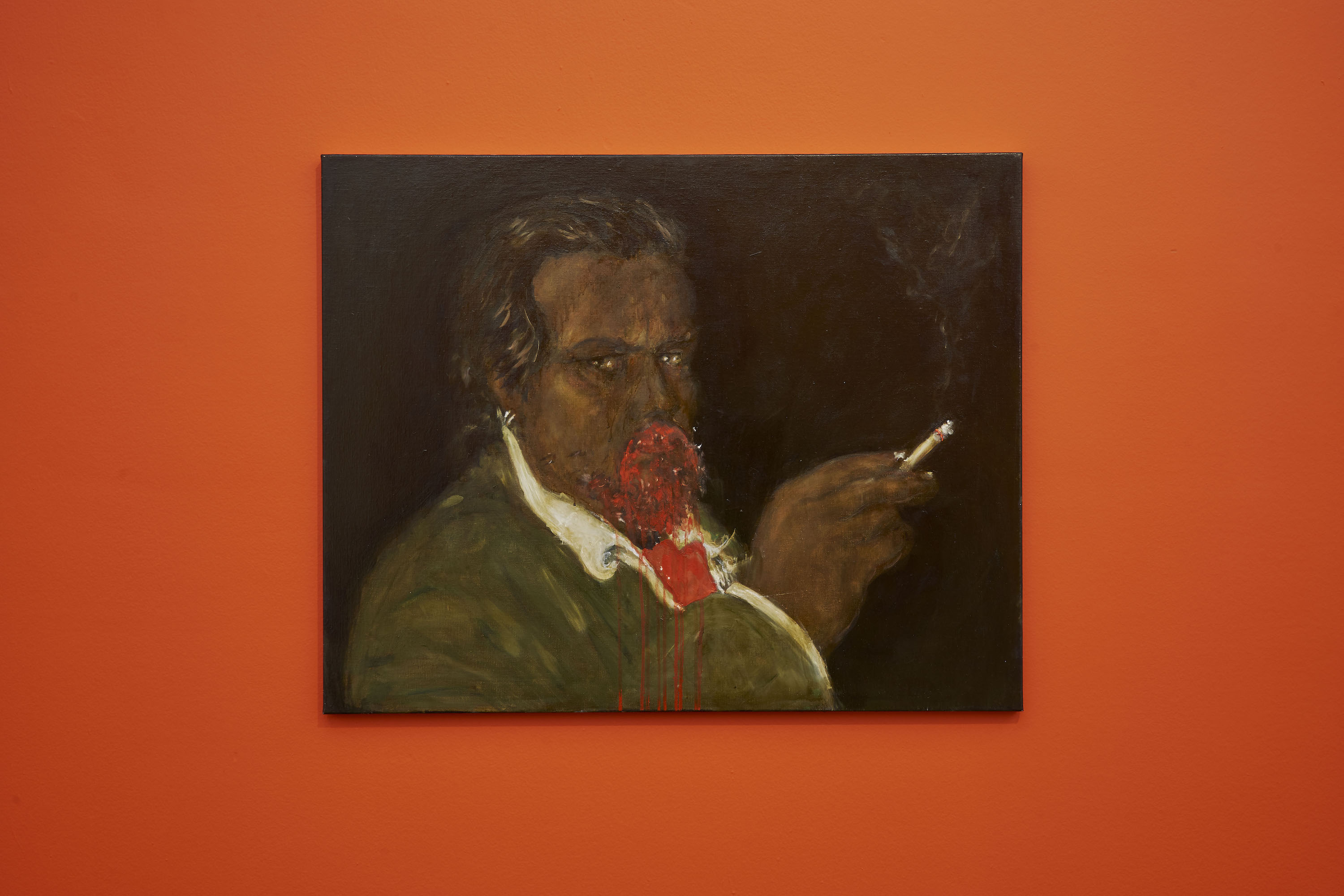

Four large-scale paintings in the main gallery figure variations on a male nude in a wash of taupe and technicolor. In each, he appears bald, white, and muscled, engaged in the performance of symbolic action. Driving the World to Destruction (1985), for example, shows the surface of a bald man’s torso, its hypertrophy defined by dark shadows. His overlarge hands hold a steering wheel affixed to the surface of the earth, whose deep greens are caught in a swirl of flames. In their rendering of male violence, these allegories are not complicated.

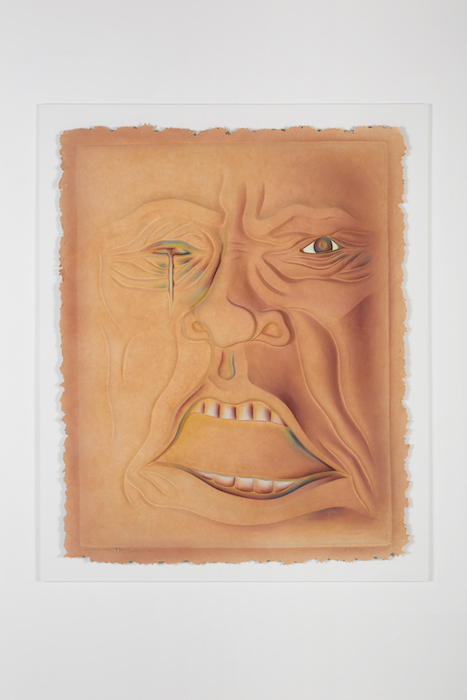

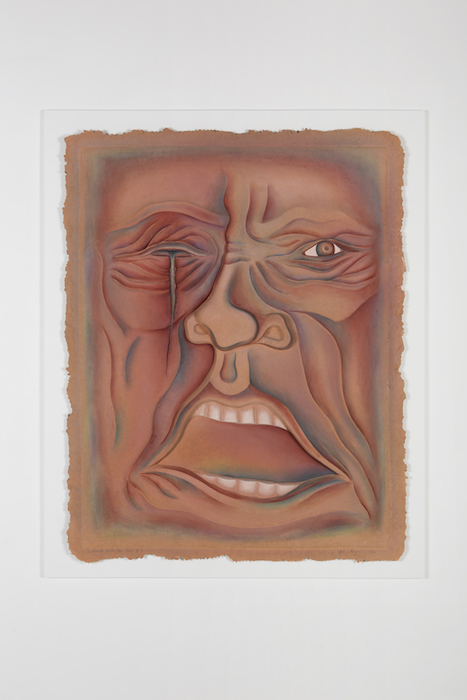

A second gallery location in Freeman Alley housed an additional suite of works on paper, whose surface is sculpted to protrude from its frame. (This part of the exhibition is now closed.) Two among these works qualify the show’s claim to prophecy: Doublehead with Green Eye Lid #2 and Doublehead with Tom Tear #12, both executed in 1986, are uncanny in their likeness to a contemporary Donald Trump. Like portraits. Their mouths gape mid-grandiloquence. The former is even rendered in powdery orange.

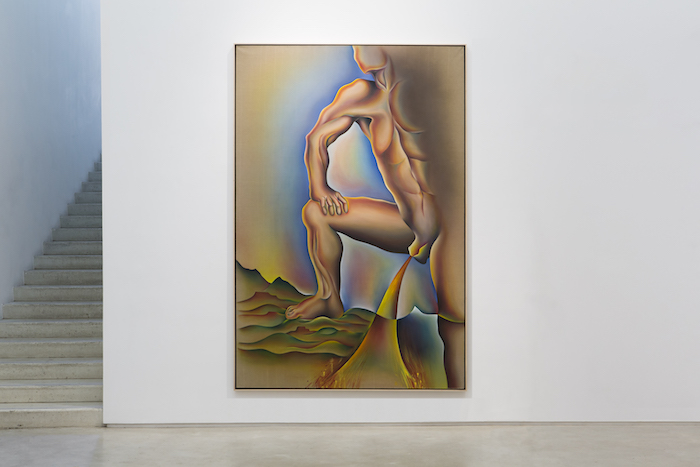

It’s a coincidence that doesn’t help the already didactic allegories at play; it’s hard not to read these paintings as literal depictions of Trump. Crippled by the Need to Control/Blind Individuality (1983) shows a man straddling the downward-facing figure of a woman as he grips her tightly by the hair. A tape recording in which Trump describes sexually assaulting women was made public in October 2016. In Pissing on Nature (1984), a man’s right foot leans into a mountain range, with his left foot rooted in a pool of blue. From the tip of his penis, piss floods the landscape in yellow. An intelligence dossier leaked early last year alleges that Trump hired sex workers to pee on the bed of a Moscow hotel room where Barack and Michelle Obama (“whom he hated”) had formerly slept.1

There’s a strange transit between the particular and the universal, here, where Chicago’s generic representations of the idea of sexual violence and the idea of juvenile debasement track so closely to the images that currently constitute American political reality. What Chicago employs as metaphors for the grotesque nature of power are not even really metaphors—not symbolic, just real, too claustrophobic to mean something beyond themselves. This proximity is made stranger by the 30 years by which Chicago’s paintings precede Trump’s presidency, though I suppose one need not exactly be clairvoyant to anticipate the ways in which violence and power pooled in the hands of volatile white men might manifest.

As staff of this publication, I edit a large volume of exhibition reviews. It’s a position from which one can observe patterns in writing about art as they emerge or expire, or congeal into platitude. Throughout the fall of 2016, we noticed repeated references to Trump; after his election in November, his name—or the epithets writers used to avoid it—seemed to make an appearance in almost every review. In most cases, Trump’s relationship to the artworks under review was tenuous, warranted neither by style nor concept. While I understood the impulse—how could one write anything that didn’t acknowledge the most obvious thing: the enormous fact of him?—we edited a lot of this stuff out.

“PowerPlay” corresponds to a discursive trend where anything in art to do with evil, psychopathy, masculinity, whiteness, narcissism, depravity, obscenity, virility, sadism, or delusion has, for the past year and a half, been critically reoriented in the direction of Trump. What happens to meaning when art’s visual cues all refer back to a single person? I worry it betrays the poverty of a discourse without more expansive referents for the monopoly of power in masculinity and whiteness. To locate these things exclusively in Trump’s name, image, speech, or body risks obscuring the structural. What metaphors might one instead use to represent the conditions by which Trump was made possible?

The exhibition’s press release cites Chicago’s desire for these works to intervene in the gendered visual order of art history, substituting the female nude with the male nude as a field for projected meaning. Though men are exceptional as subjects for Chicago, the series is consistent with her career-long study of how gendered bodies are seen. Her central core imagery—those biomorphic petals that feature in The Dinner Party, for example—can be understood as a visual language that uncouples the fact of a woman’s body from the desires of others, or at least to make their connection less automatic. One could argue, however, as some of Chicago’s contemporaries have, that women’s bodies are so deeply coded as sexual objects in the patriarchal imaginary that simply depicting them—in however abstract, formal, or celebratory terms—is an insufficient critical intervention in the closed loop of the male gaze to reclaim the body from objectification.

Similar limitations are present in “PowerPlay.” How bodies are represented in cultural forms works as both a diagnostic for power as well as its conduit; to produce images at odds with a gendered visual order can necessarily only address one of these functions. It seems as though Chicago’s work is currently subject to an overdue critical reappraisal, though the timing is a bit awkward, as the shortcomings of using vaginal iconography to represent womanhood are increasingly recognized in feminist discourse. One wonders if “PowerPlay,” like Chicago’s central core imagery, pictures gender as a natural class rather than a social or political one.

Ken Bensinger, Miriam Elder, and Mark Schoofs, “These Reports Allege Trump Has Deep Ties To Russia,” Buzzfeed, January 10, 2017, https://www.buzzfeed.com/kenbensinger/these-reports-allege-trump-has-deep-ties-to-russia?utm_term=.iuj5PVA1N#.ud7OE9MlD