March 27–30, 2025

Tsai Ming-liang’s Vive L’Amour (1994) and Marion Scemama’s Relax Be Cruel (2024) are, at first viewing, very different films. Vive L’Amour tells the story of a realtor, her lover, and a young ossuary salesman, all of whom are secretly frequenting the same vacant apartment in 1990s Taipei. Relax Be Cruel is a lightly fictionalized document of 1980s New York warehouse Pier 34. Scemama’s whimsical narrative, shot in black-and-white, follows a young inhabitant of this crumbling industrial space who glimpses the other people who sleep, cruise, and work here.

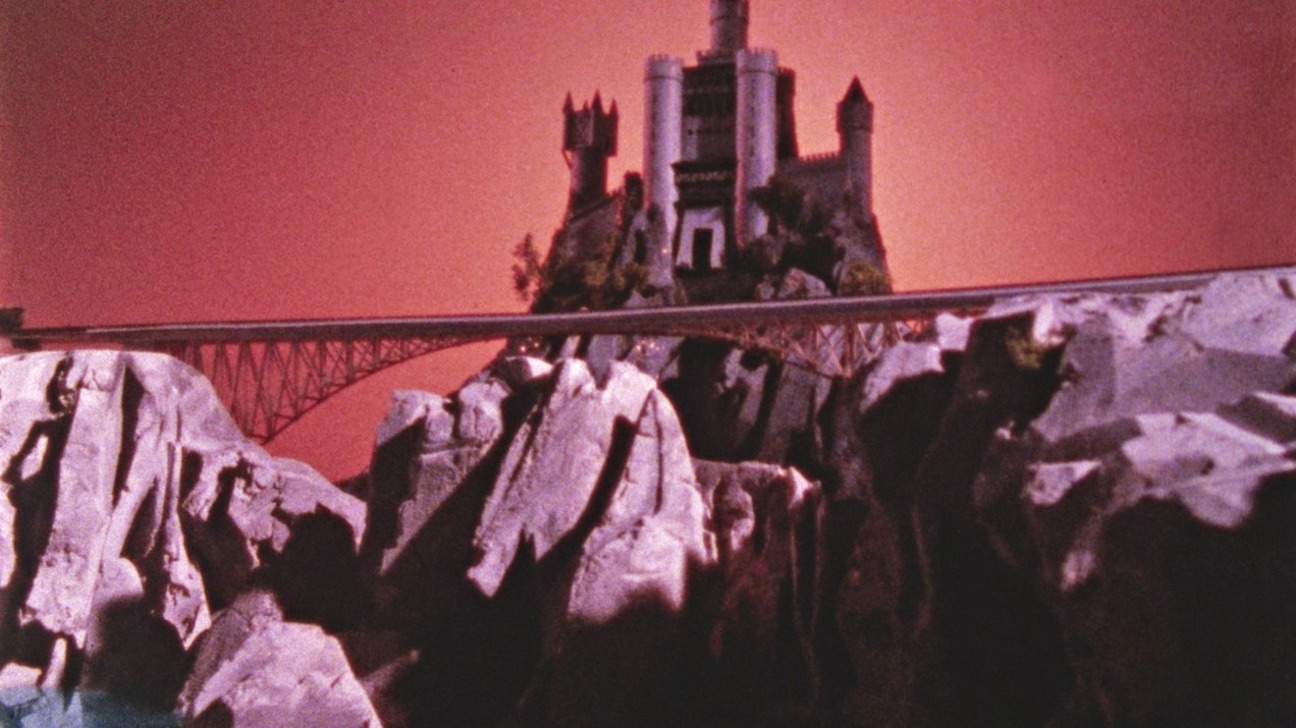

The two films—shown at BFMAF on consecutive nights in the same space—share a premise: people are making the same place home, without knowing that the others are there. It’s a domestic story that is also political: in both works, as in other stories of clandestine cohabitation such as Florian Henckel’s The Lives of Others (2006) or Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite (2019), the camera tracks from open, central areas, into hidden zones and blind spots, discovering more than the characters themselves can understand about their home. This all feels very close, right there in the bathroom and the bedroom, but it’s also always an image or microcosm of other, bigger battles over space.

Stories of colonization and occupation were very apparent at BFMAF, as they are around the world, and in any news cycle now. Philip Rizk’s program on Frantz Fanon’s conception of neocolonialism, “Ways of Seeing Fanon,” opened with Raoul Peck’s documentary Lumumba: Death of a Prophet (1991), which relates how European politicians orchestrated the torture and murder of Patrice Lumumba, Congolese prime minister and a friend of Fanon’s, in 1961. Behind Berwick’s old defensive walls, in a former military gymnasium, Adam Piron’s installation Black Glass (2024) looked at the United States army’s seizure of Modoc homelands in the nineteenth century. Some Strings (2024), exhibited at St Aidan’s Peace Church, is a 300-minute, multi-authored work made in memory of Palestinian poet Refaat Alareer, who was killed in Gaza in 2023. Alareer had been reporting from Gaza to international news agencies. Researchers found that the apartment he was in with his family was “surgically bombed out of the entire building,” that is, Alareer was targeted personally by a weapon directed into his home.1

The program at BFMAF has no set theme or formal approach, and finding common threads between the works here isn’t really necessary, though I found my mind did it anyway. In the press materials, director Peter Taylor has described the festival as “a work in progress,” “fluid,” and “pluralist,” a place for difficult conversations. This year’s filmmakers in focus were Brooklyn-based Ayanna Dozier, whose shorts examine sex work, racialization, care, and fanaticism in contemporary America; and Tokyo-based Eri Makihara, whose almost silent films explore D/deaf experiences in a hearing world. There were films (including Scemama’s) set in New York during and around the AIDs crisis; and new projects from Berwick’s local area, such as Stepney Western (2025), a documentary about young adults and horses at a community riding school in Byker, Newcastle. I was skeptical about Stepney Western: I thought it could very easily patronize the vulnerable teenagers and captive animals that it took for a subject. But the story was carefully researched and its narrative is plainly told and deep.

Perhaps the reason my mind kept identifying connecting threads across this rangy program is that the festival, and the town, are small. There are usually two films scheduled at one time, with five installations around town. If the showing you wanted to see has sold out, you’ll have to go to the charity shops or the leisure center (it’s a good one, with mini water slides for children and very small filmmakers).

This fact, that Berwick isn’t especially cosmopolitan, is one of the observations that sometimes comes to hand in write-ups of the festival, but it would seem to assume a baseline scale or native habitat for film festivals and conceptual works—as though a market town is somehow less contemporary than Berlin, Venice, or Shanghai. I don’t think that’s true. When I came to Berwick my train passed a prison and decommissioned coal mines, then a silo for a Scottish broadband supplier, a scrapyard full of detached screens and windows, and a barley processing plant that distributes malt to New Zealand, South Africa, and Japan. This is a fair setting for a fluid, pluralist, work-in-progress program—a political conversation that takes focus in a small space.

Amid all the violence that made itself apparent in this year’s program, something very different kept coming up: a delicate, ultra-close relationship with the human body’s barest gestures. Lumumba is a tale that emerges from King Leopold of Belgium’s colonization of Congolese lands, and therefore a story of extreme historical violence. We see slaughtered animals, a severed human hand (amputations were, notoriously, a key part of the colonial government’s brutal police enforcement), and footage of Lumumba being beaten after his arrest. There are also two inspired sequences of lingering, intimate, and generous attention to bodies. Peck’s camera looks closely at historical photographs of groups of Congolese and Belgian men. His voiceover observes that these men were drawn together in that place at that moment by a white king’s greed. He speculates on their lives, moods, and dreams, as his camera looks carefully at their facial expressions, hand gestures, and gazes.

In Scemama’s When I Put My Hands on Your Body (2014), a work filmed in the context of the AIDs crisis, a man plants butterfly kisses on another man’s bare skin. Dozier’s Let’s Make Love and Listen to Death From Above (2023) also watches two men making out, the camera tracking their hands as they travel up and down one another’s bodies, inside pockets and below waistbands. The silent soundtrack amplifies this physicality, as it does in Makihara’s near-silent The Tanaka Family (2021), which looks closely at the frantic bodily proximity that comes into play when an adult needs physical care. A carer tests the heat of the shower on her own fingertips; wipes her charge after a nappy change; dabs drips of spilt food from his chin.

In separate conversations at BFMAF, Makihara and Scemama both spoke about how they had used close-ups to evoke embodiment—something “sensual,” in Scemama’s words; Makihara talked of “hearing with the whole body.” In Stepney Western there are many long, held moments of tenderness seen in close-up: nosing, stroking, grooming, whispering, nuzzling. We see child and horse standing together, literally leaning on one another. This is an extremism of gentleness, here shared between two individuals who are both, in the wider world, powerless. I wondered whether this precious mode of attention to the human body’s littlest gestures, units of contact, is a form of resistance to the large-scale violence in which it is inset, or whether it’s a last retreat: the bare, minimal remnant of kindness or pleasure that is still available.

“Israeli Strike on Refaat al-Areer Apparently Deliberate,” Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Monitor (December 8, 2023), https://euromedmonitor.org/en/article/6014.