December 2, 2020–May 9, 2021

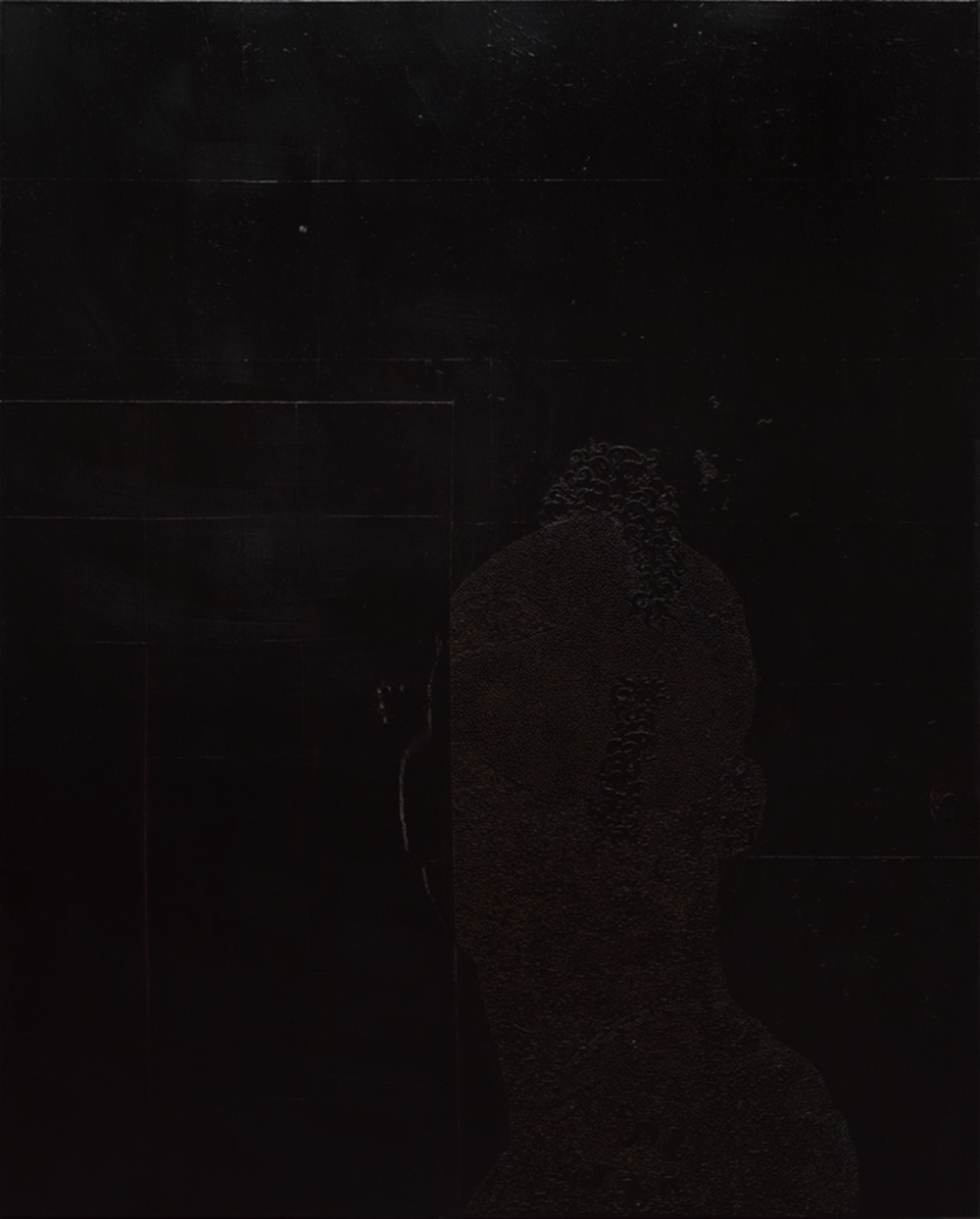

In the foyer outside Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s exhibition, a question is written on the wall. “What sounds can you hear when you look at the paintings?” Music spills from a hidden speaker; Miles plays. I can hear the way he held his horn, so closely attuned to the spaces he could inhabit within a melody, perhaps looking for a nod from his band, or, more likely, improvising, always improvising. Feeling rather than knowing.

When I enter the space, it is quiet. The music has stopped, but looking at the paintings around me I still hear Miles and Bill and Gil, Fela and Ebo, Solange and D’Angelo: the music Yiadom-Boakye had playing in the studio when painting. A tradition of rhythm rendered on canvas in blues and greens, yellows and reds. In this way, it is possible to see something and to hear it too, and I wonder if this is what feeling is.

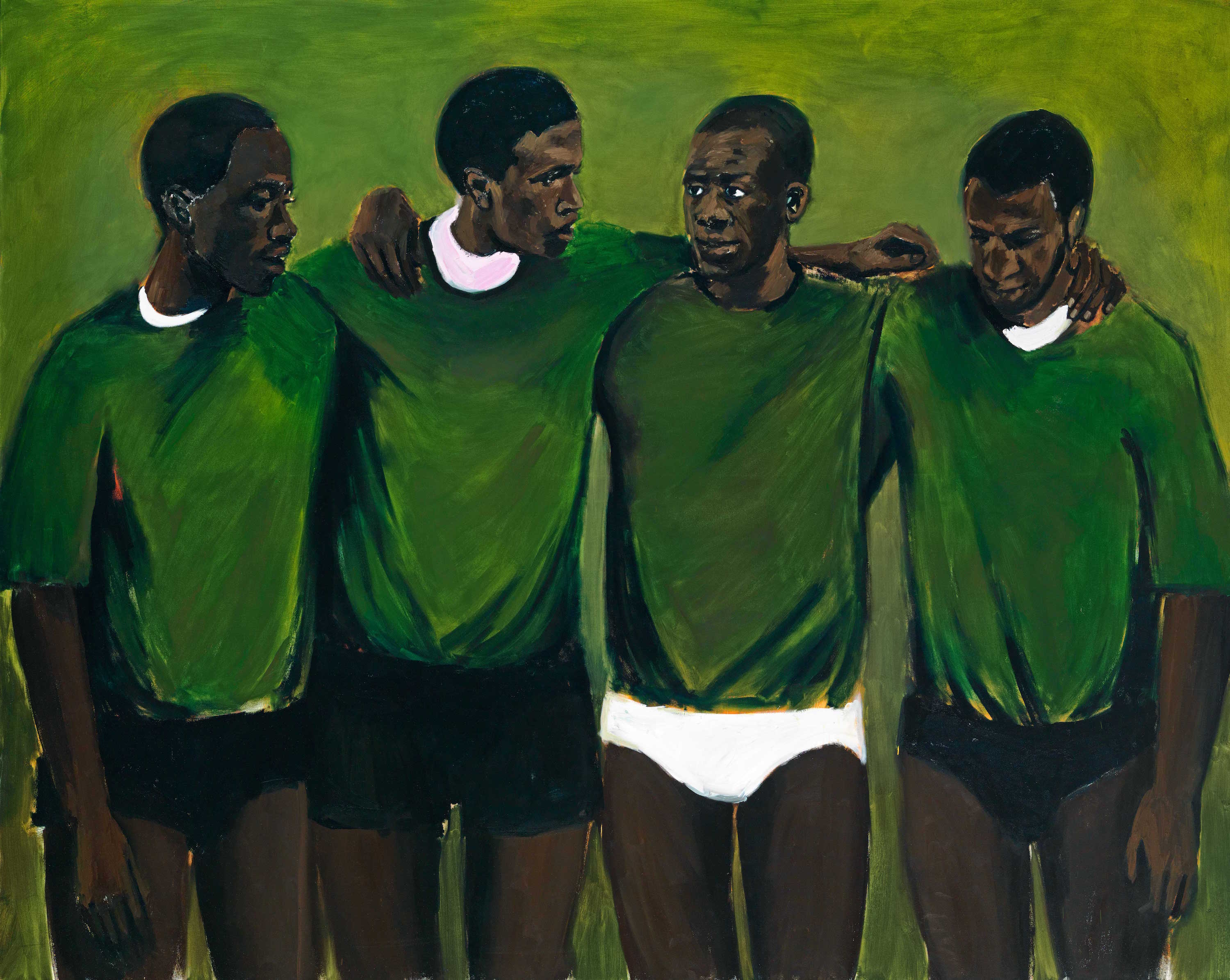

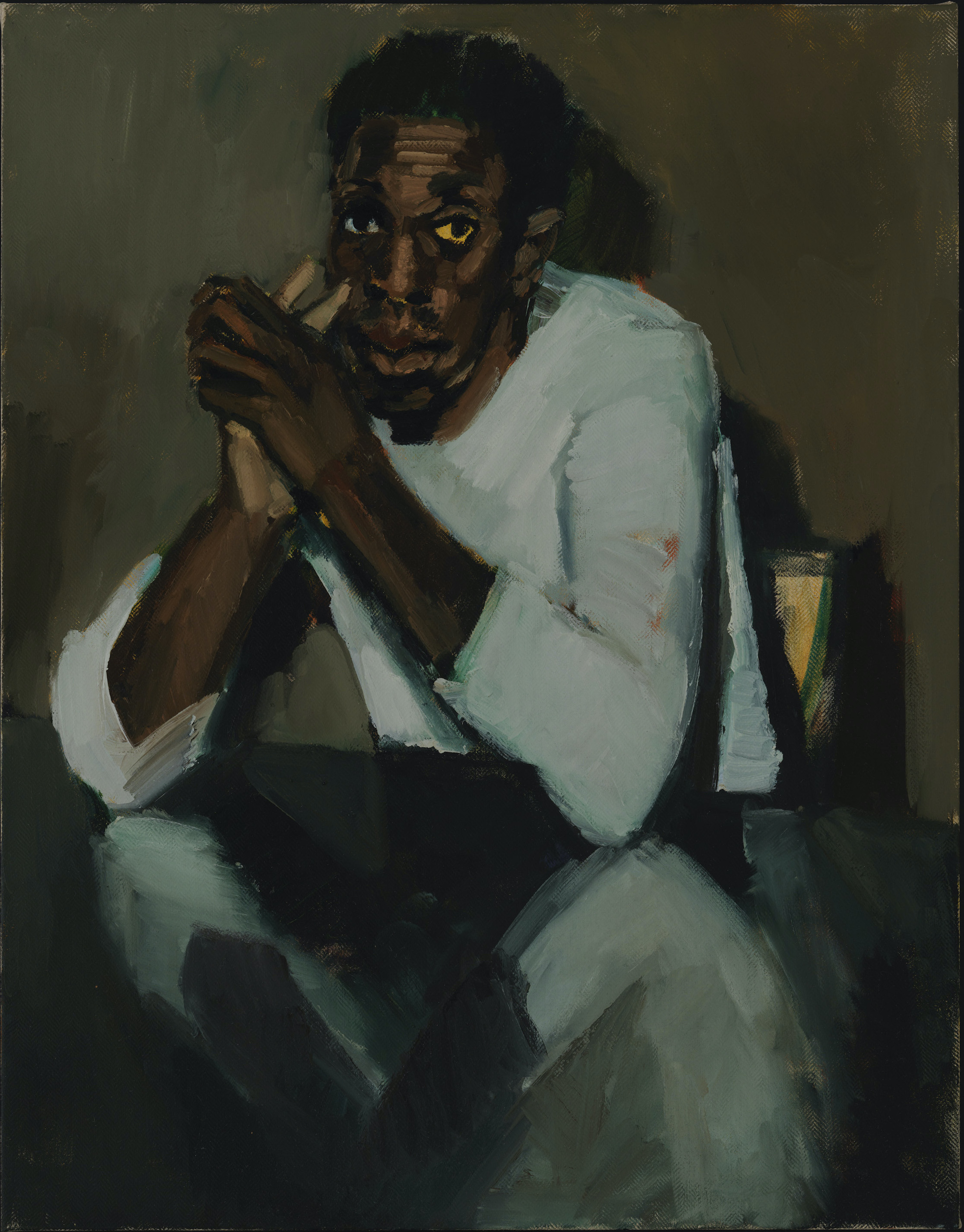

What I do see: Black figures, in all manner of poses and activities, caught in private moments. They tease and taunt, they are in repose, they squat, they crouch, they hurt, they ache, they joy. They are quiet but never silent. In Later or Louder or Softer or Sooner (2013), a woman gazes off elsewhere, holding her hip, you know the one that’s been hurting? In An Education (2010), an older man holds court amongst friends, his hands talking for him as they do when he’s excited, in full flow. Groups gather and clink glasses, or stretch before dance practice, or smoke an evening away. There’s so much room for each figure to live and breathe. All around the gallery, figures face off, within the same canvas, or adjacent, across the room, in separate vestibules. The space is quiet, but the paintings encourage conversation: with each other, with ourselves.

As I move through the show, I often turn my head and find myself shocked at the appearance of another canvas. Later, when the shock has worn off, I realize this is the wrong word. I was astonished, astonished to see myself at various intervals. I was astonished to see feelings I knew. Yiadom-Boakye has previously said she does not think of her ancestral home, Ghana, as a home, but rather as a way of thinking, a way of seeing. Perhaps then, as someone of Ghanaian heritage, I was not seeing myself, but the way I see the world.

So many of these figures are still. They are engaged in the ordinary, in the everyday. They peer out towards us, knowing they are at the center of the narrative, knowing there is freedom in this. But nothing much happens. There are no tricks, no sleights of hand. There is little to distract; the canvas is uncluttered. It’s all mood: the gaze, the lack of period. Undefined landscapes, of tones which are muted yet full, might imply a lack of rootedness, but on closer looking suggest a sort of infinitude. Suggest that on the canvas, anything is possible. In this way, the background is as important as the fore; the life of a figure is as important as the singular moment that’s represented. And her figures! They are fictive models, arranged from scrapbooks, collected images, from photos, from life, with the aim of building a language in which black life takes on infinite possibilities.1 But if fiction is working from memory, then what we are seeing is recall, investigation, interrogation. What we are seeing is as real as the moods conjured, as the emotions felt. What we are seeing, through the gaze—figures’ eyes are often the only light in dark paintings—is a thinking through feeling. We are seeing the artist offer an extension of herself: of the way she sees, the way she feels. Her angsts, her joys, her aches, her loves.

Walking through the gallery, engaging with the pieces hung at eye level, I’m reminded of family photo albums, in which, like here, people dance and swim and smoke, across a period of many years. In which people do nothing, which is everything. These quotidian practices are an indication of being alive, of soul. In the corner of the living room of my family home, there is a stack of such albums. Picking up any of them, one would find black people dancing and swimming and smoking, engaged in collective joy, lost in private ecstasy. Inside the exhibition, as in the family album, one begins to see the through-line. I think it’s because of the hand from which the image has been made: to be seen, knowing that the resulting images will create a space in which we exist for ourselves, rather than for the pleasure of others.

There is a careful and measured employment of repetition throughout. In Diplomacy I/II (2009), we see the same scene at day and night, the same ominous and tender gathering. I see gestures and stance reappear, figures who seem to have aged. But, much like in jazz, the same phrase never sounds the same. We have changed moment to moment, and so has the artist. This continual repetition comes as a recall, a rendering, an interrogation of who she is; creation, not as a means to an end, but as a process of lifelong discovery. In Yiadom-Boakye’s own words: “It’s also another form of anchoring: you revisit something or someone in order to anchor yourself to a body of work, to remind yourself of a bunch of reference points, or ideas or thoughts or feelings.”2

Through all this, what remains is the simplicity of harmonies, and the freedom of improvisation. There is no escaping the feeling of having been graced by something beautiful, by some sort of love. There are sounds, these gorgeous, full figures, there is mood, there is soul. There is feeling. And yes, nothing much happens. But this is everything.

Antwaun Sargent and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, “Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Speaking through Painting,” Tate Etc., 13 October 2020, https://www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-50-autumn-2020/lynette-yiadom-boakye-antwaun-sargent-interview.

Ibid.