April 18–September 28, 2025

Murderers Bar (2025), the centerpiece of this show, is the final chapter in Lucy Raven’s vauntingly ambitious trilogy The Drumfire, which riffs on cinematic representations of the settlement of the American West. The first, Ready Mix (2021), focused on the production of concrete in a plant in Idaho, while the second, Demolition of a Wall (Album 1) and Demolition of a Wall (Album 2) (both 2022), honed in on pressurized blasts from a military explosives range in New Mexico. The video installation Murderers Bar examines the removal of a dam and the restoration of the Klamath River in California. The word “drumfire”, referring to the sound of steady intense artillery bombardment, dates to the same period in the early 1900s, when four hydroelectric dams were built along the waterway, cutting it off from the ocean, terminating the run of millions of salmon, and eliminating a primary food source, and spiritual symbol, of the Indigenous bands living alongside it.

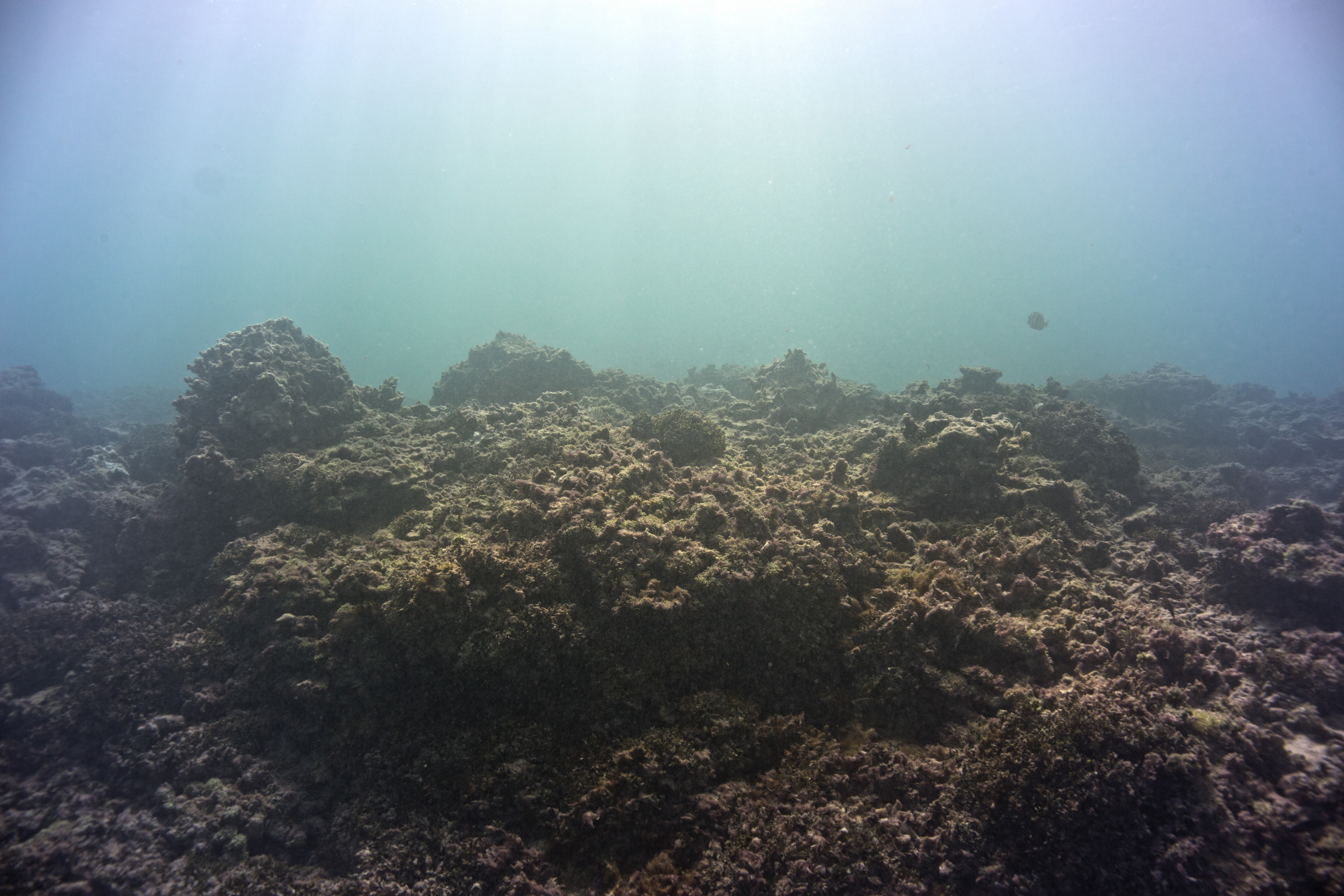

A curved vertical screen faces lux aluminum bleachers edged with chain link mesh. From the benches, it does feel as if an iPhone screen has morphed into an iMax theater. Over the next forty-two minutes, visitors watch as a drone camera skims the surface of the Klamath River, dives underneath its muddy waters dissolving into computer-generated imagery, and then emerges to soar high above it, winding along the bends of the stream until it reaches a dam. In one powerful scene, the black-and-white footage shifts to color as it surmounts the stepped concrete façade, helped along by the intense, emotional arc of its score, composed by Deantoni Parks. The camera, which has so far been moving steadily towards its face, now turns around to reveal the utter devastation behind it: a lifeless riverbed, its banks a barren wasteland. Where there is no water, there is no life.

In the 1840s, during the gold rush, the name “Murderers Bar” was given to a fluvial landform along the waterway running between California and Oregon. The lore is that a settler came upon an abandoned camp with calcined bones and the hair of whites and “Indians” strewn around, and carved the words into a tree as a warning signal to other prospectors. In adapting this story as the title of her show, and through the works themselves, Raven treats violence as a motif. Her work creates an equivalence between the dangers settlers faced in search of gold and the First Nations, who were subject to forced labor, dispossession of their land, and genocide. “Murder” also refers to a roost of crows, gothic symbols of death, which in some cultures are signs of wisdom and luck. The dispersal of the birds in the film is ominous, like the gunshot explosions echoing throughout its score, a clear—if simplistic—reference to settler violence. A blinding white flash also suffuses the screen at intervals, perhaps a nod to the “Western” genre whose emergence was simultaneous with the birth of cinema.

Accompanying the film are four works entitled Deposition, Dam Breach 19, 18, 24 and 11 (all 2024). Made of silk, sand, dirt, cement, saltwater, wood, and aluminum, these“‘drawings”—or “proto-photographs”—are remnants of models constructed to simulate the dam and its breach. A group of artists engaged in a lively debate at the opening, ultimately deciding they were monoprints, distinct impressions of an image. They couldn’t be photographs, as there was no chemical process involved. Whatever the media, their installation feels unresolved at best and overwrought at worst. The silk stretched on hefty aluminum frames resembles high-end mechanized blinds. The work clearly references land art, particularly Robert Smithson’s dialectic “Site/Nonsite” with its referential images of a landscape displayed alongside sculptures made with geologic materials from it. A more compelling image came from Raven’s slideshow, showing the fabric hung from a structure of wooden two-by-fours in her studio, reminiscent of the process-based material experiments of Beverly Buchanan, Ana Mendieta, and Zarina. Excluded from the categories of land art and Minimalism, their work countered its violence and slickness.

Raven, by contrast, is compelled by spectacles of ruination. Demolition of a Wall takes its title from the Lumière brothers’ 1896 film, which was originally screened forwards and then backwards, with audiences marveling at its illusionistic reconstruction. Viewers of Murderers Bar experience a similar jouissance, but one solely of destruction. It is notable that the trilogy is largely depopulated. In one scene in Murderers Bar, the small aperture of a tunnel floats in an otherwise black screen, while men in orange vests load explosives into the dam’s subterranean walls. After the breach, there is a close-up of water gushing out of a pipe, followed by a long shot from a helicopter, whose shadow falls on the glinting river as it cuts through a verdant landscape, following the river to where it meets the Pacific Ocean. The dam, however, has not been breached by these avatars of governmentality, but by the Yurok, Karuk, Klamath, Shasta and Hupa Tribes whose activism stretches back to the damming of the river by the US Army Corps of Engineers over a hundred years ago.

During the opening of Murderers Bar, Raven explained that she had wanted to make a film with “the river as a protagonist.” It’s a beautiful sentiment, but it is actually visual technologies that are its main subject. In The Drumfire, she sets herself the formal challenge of optically capturing the thermodynamics of human-made changes to the built environment—the making of a material substrate, pressurized blasts pulsing through land, and water breaching a dam. Unlike Harun Farocki, whose critical cinema revealed the use of images as “technologies of control,” in Raven’s depopulated films, people and their labor, landscape and toxicity, settlement and genocide, are peripheral to the story. Like the expansionist myth of manifest destiny that continues to shape the North American cultural imaginary, the film is filled with wonder for the American technological sublime.