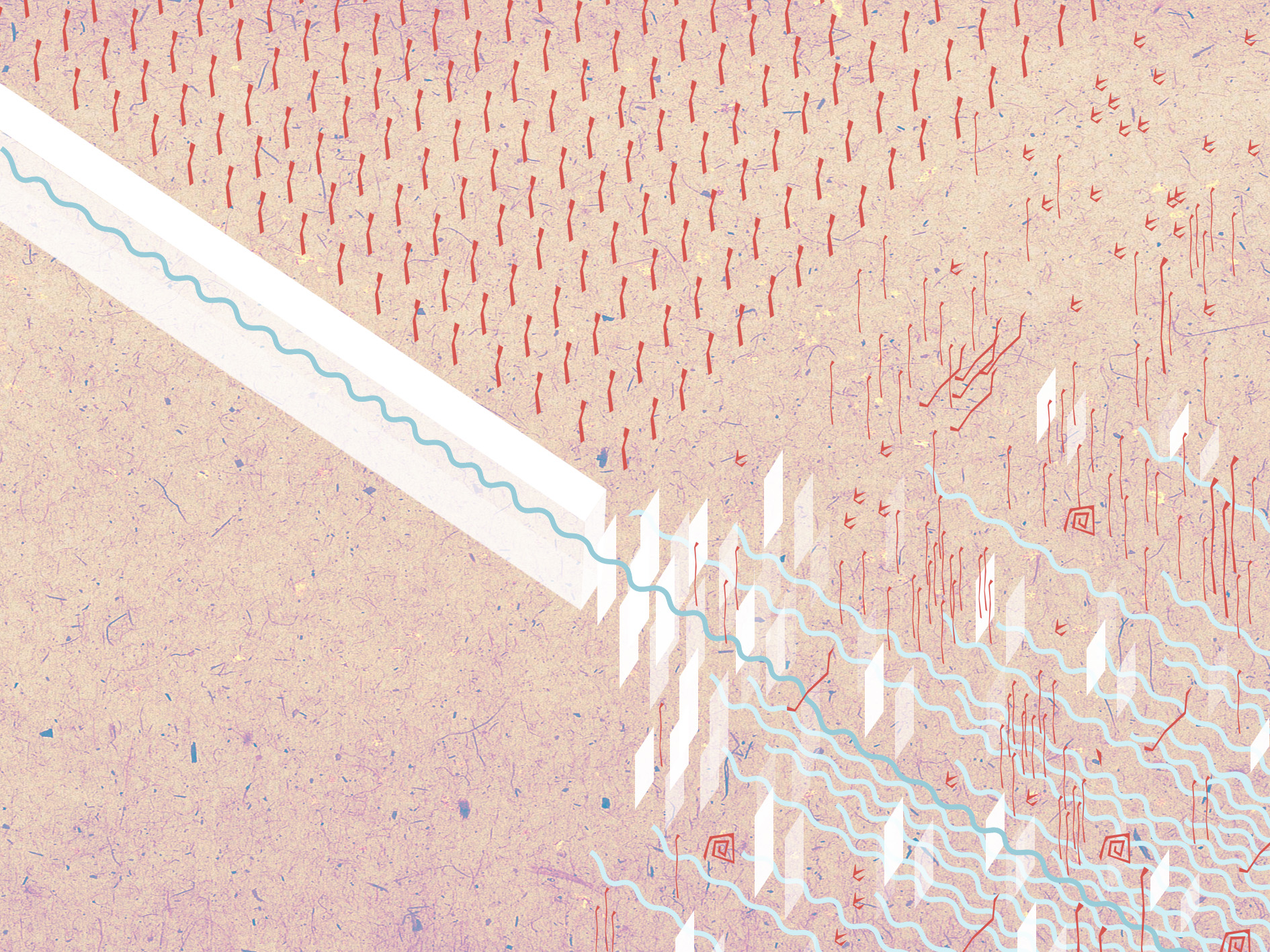

Nina Porter’s photographs present studied variations on a theme. Hanging uniformly in neat, linen-lined frames, each image is grounded in a radius of light, the aperture of what we come to discover is a pinhole camera fashioned from a backpack. Variously over- or under-exposed, the images are semi-abstract, like surrealist studies in photosensitivity. It is only after learning that they capture the interiors of medical examination rooms that the edges of venetian blinds, a curtain separator propped on castors, or a tangle of plastic tubing become legible.

The image is “taken” (or perhaps more aptly, “begun”) after Porter enters the examination room and is prompted to remove her backpack. The capture stops when the appointment ends, the backpack replaced, Porter’s spine acting as shutter, sealing off the aperture. The quality of the image, then, is determined entirely by the length of the doctor’s visit, so that the immediate impulse is to draw a parallel between the sharpness of the image and the standard of care presumed to have been administered, the photo paper functioning like a stopwatch, tracking time. In this way, the representational credentials of the photograph no longer matter; what is depicted in the image becomes less important than how it was made. The analog process captures a material duration that comes to stand in for the patient’s experience.

The dreamy edges and blurred haze code each photograph with intimacy; they read almost as bedroom shots, quiet talismans not for public consumption. Taken together with the camera’s dependence on Porter’s body, the temptation to read the artist into the work becomes unavoidably strong. Porter, however, intentionally excludes her personal details: we do not learn the reason behind these appointments, nor are we given any insight into their frequency. This meticulous omission creates a curious tension at the heart of the series. Because though we certainly do not need to know the explicit circumstances that brought Porter in and out of so many medical complexes, the resulting images nevertheless demand to be treated as a kind of evidence. The residue of an engagement, they become a study of care, which is, at its best, individuated, tailored, and specialized. It is, in other words, personal.

That each image is titled like a mnemonic, named by the square footage of the room and the position of Porter’s body throughout the appointment (i.e. seated, reclining 35m3, 2025), only exacerbates the absence of autobiographical detail. The information that is provided simply underscores all that is not, and still we’re faced with the inescapable impression that these photographs function as a kind of proof. Closer to testimony than souvenir, they speak to a specific time, place, experience; the precise shape of which the viewer will never completely know. Still, saturated as we are by fleeting, immaterial digital imagery—the constant need to log further underscoring how we increasingly use the photograph as a tool to record and remember—Porter’s suggestion that the documentary value of an image can be located as much in its objecthood as in the subject it captures is refreshing.

This attention to materiality carries over to the constellation of spherical wooden cameras dotting the floor at the back of the gallery. They have never been used, but are instead inscribed with a date in the future on which Porter, contractually, will fill the orb with photosensitive paper and make an image. In an almost perfect inverse of the images hanging on the gallery walls, the cameras promise a future human connection, so long, that is, as they are properly cared for. So long, that is, as both parties—artist and collector—are present to fulfill the contract, a fact that looms lightly but not insignificantly. The resulting images will be a different kind of portrait of care, a testament to what will have been rather than a log of the act itself.

In redacting the autobiographical context, Porter isolates the idea of care, elevating it as the primary subject of the work—something provided, undertaken, and submitted to. But this framing begs the question of whether true care can ever be neutral. The effort to foreground the act of care, and especially its seeming futility, offers a searing critique of the increasingly rote, codified, and systematic way we relate to one another. The best care, the work seems to suggest, is rooted in genuine curiosity and the willingness to be surprised.