April 5–July 6, 2025

Two hours northwest of Tokyo, in Saitama prefecture, is the Maruki Gallery. Opened in 1967 by an artist couple, Iri and Toshi Maruki, it is today the permanent home of their Hiroshima Panels (1950–82), a harrowing series of vast paintings based on eyewitness accounts of the atomic bomb’s immediate aftermath. Initiated during the American occupation, when such depictions were prohibited, a major early tour of these works played a vital role in bringing wider attention to the horrors of nuclear warfare. The Hiroshima Panels are a resonant backdrop for this revelatory exhibition, one that ruminates on testimony and collectivity, on art’s capacity to act in the face of crisis. It is a compact presentation that seeks to do nothing less than rewrite twentieth-century Japanese art history.

Katsura Mochizuki lived many lives: anarchist and advocate for revolutionary art, printer and political cartoonist, agricultural reformer, and school teacher. The son of a silk farmer, he was born in Nagano prefecture in 1886. Early landscapes made while still a teenager evoke a region undergoing rapid industrialization. Scattered among these peaceful scenes are hints of future eruptions and collapses: a volcano, flood plains, a power station. Mochizuki graduated from Tokyo School of Fine Arts in 1910, and spent the next decade working as a teacher and lithographer before opening a diner, which became a hub for anarchist meetings.

A monthly study group dedicated to proletarian art quickly morphed into the Kokuyōkai collective, which Mochizuki founded at his home in 1919. This avant-garde group comprised artists alongside members from the worlds of literature, theater, and activism (their moniker translates as “obsidian,” apparently chosen for its premodern gleam). Several years before the emergence of the better-known Mavo group, Kokuyōkai organized some of the first independent exhibitions in Japan, as well as performances and a journal, before disbanding in 1922.

Despite his leading role in these activities, until now Mochizuki’s own work has remained barely exhibited and hardly known. During the pandemic, his grandson opened his family’s collection to a research team of curators, artists, and archivists, assembled by art historian Gen Adachi. Together they developed this landmark project, contributing detailed object labels and a zine, alongside a stripped-back exhibition design and short video response. Several members of this team have been prominent activists in the wake of the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster, and make a compelling case for Mochizuki’s importance to ongoing debates around questions of ecology, community, and resistance. The exhibition argues, as per the title of one of its seven chapters, that Mochizuki and Kokuyōkai’s activities constitute the “starting point for contemporary art” in Japan.

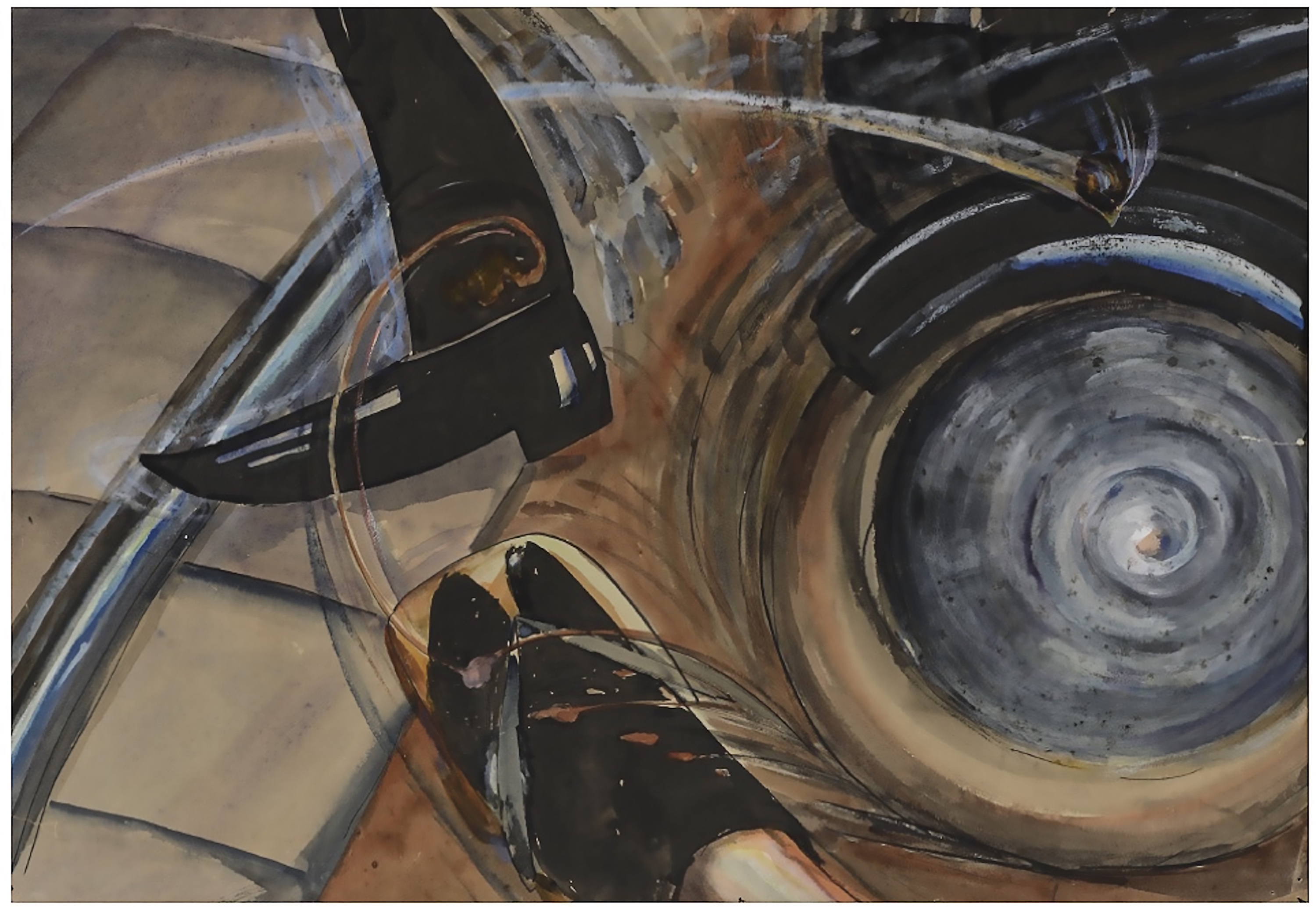

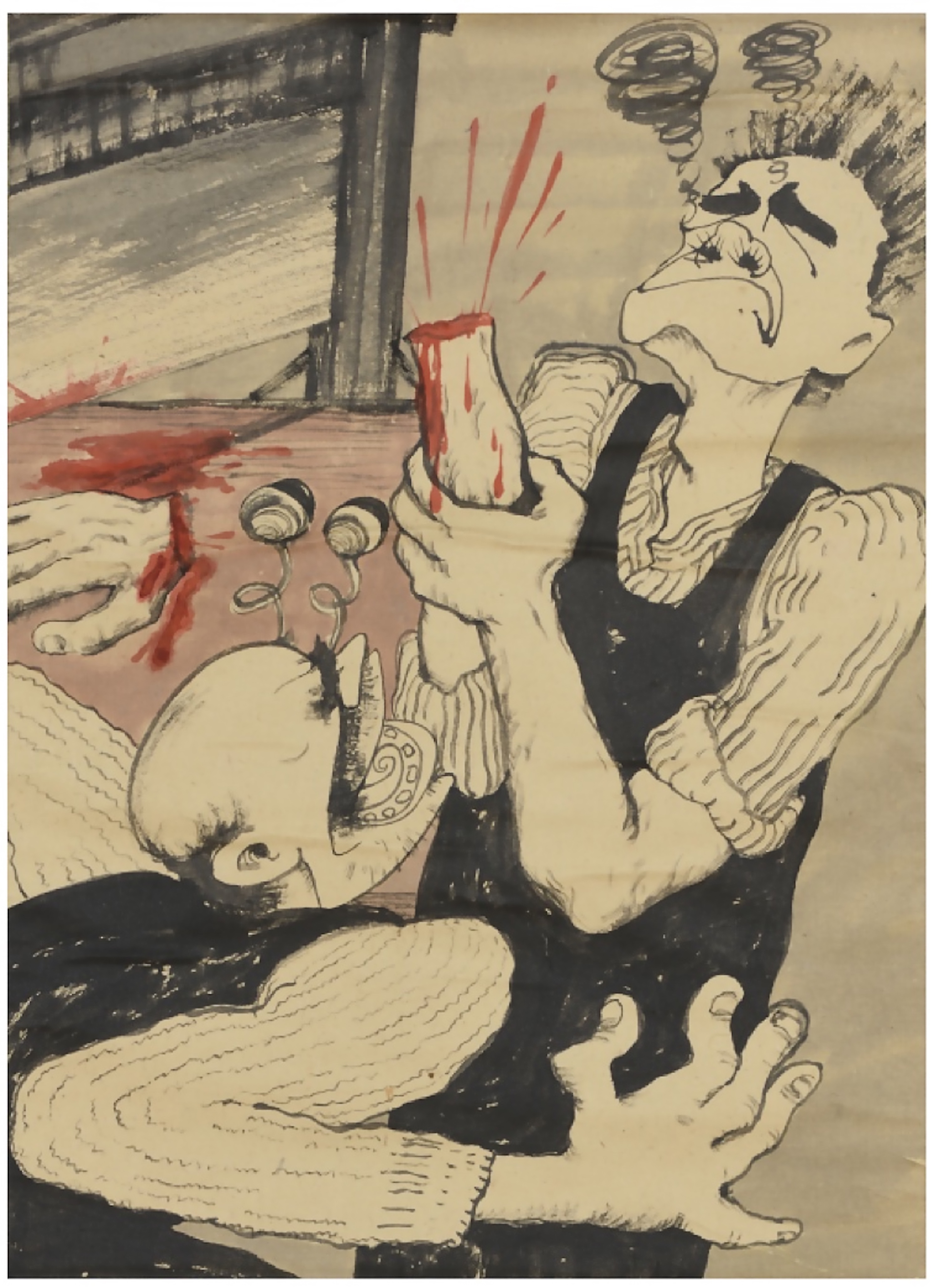

The main gallery is devoted to the 1920s, a time of persecution for the Left in Japan. Mochizuki’s most striking works from this decade were presented at Kokuyōkai’s open-submission exhibitions. They are full of bitter humor, not to mention bombs, smoke, skulls. Mochizuki had visited the first Futurist exhibition in Japan in 1920, and these works vibrate with motion and flickering after-images, while forming a coruscating critique of mechanization. In the mordantly titled Is the Machine Ok? (1920), a printer’s hand has been severed, his supervisor screaming, eyes popping out on stalks. Another work from the same year—of feet on a busy street—is less obviously incendiary, but is titled Rebellion. When the exhibition opening was raided by the police, it was immediately confiscated.

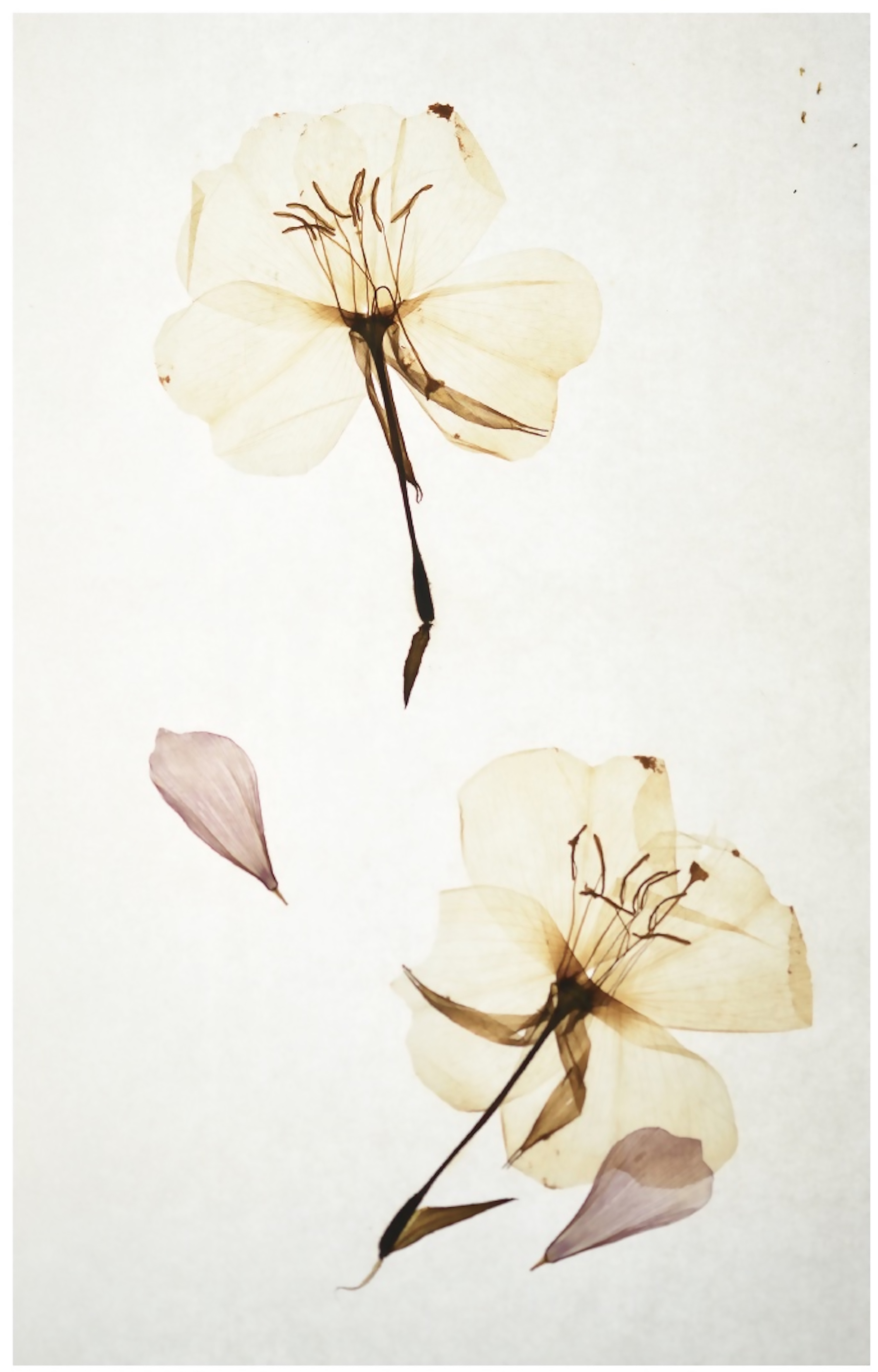

Much of Mochizuki’s work from the 1920s is acutely interested in violence or, more precisely, what is done—and who profits—under cover of emergency. His close friend Sakae Ōsugi was a charismatic leader of the anarchist movement, as the curators write in the accompanying publication, “Perhaps the coolest man in modern Japanese history, but also the most hated.” (Mochizuki painted Ōsugi's portrait, and collaborated with him on an illustrated book.) In 1923, when the Great Kantō Earthquake killed more than 100,000 people and destroyed half of Tokyo, martial law was declared. Amid violent crackdowns on Koreans and dissidents, military police murdered Ōsugi, his partner, and young nephew. Seeking revenge, members of their circle made a failed attempt to assassinate an army general, resulting in further rounds of arrests. Mochizuki’s friend, the poet Kyutaro Wada, wrote from prison, “I want to make a flower bloom from the afterlife,” before committing suicide in 1928. Mochizuki scattered Wada’s ashes in his garden and planted primroses, which he pressed and posted to friends—a proto-mail-art piece titled Flowers from the Other World (ca. 1929).

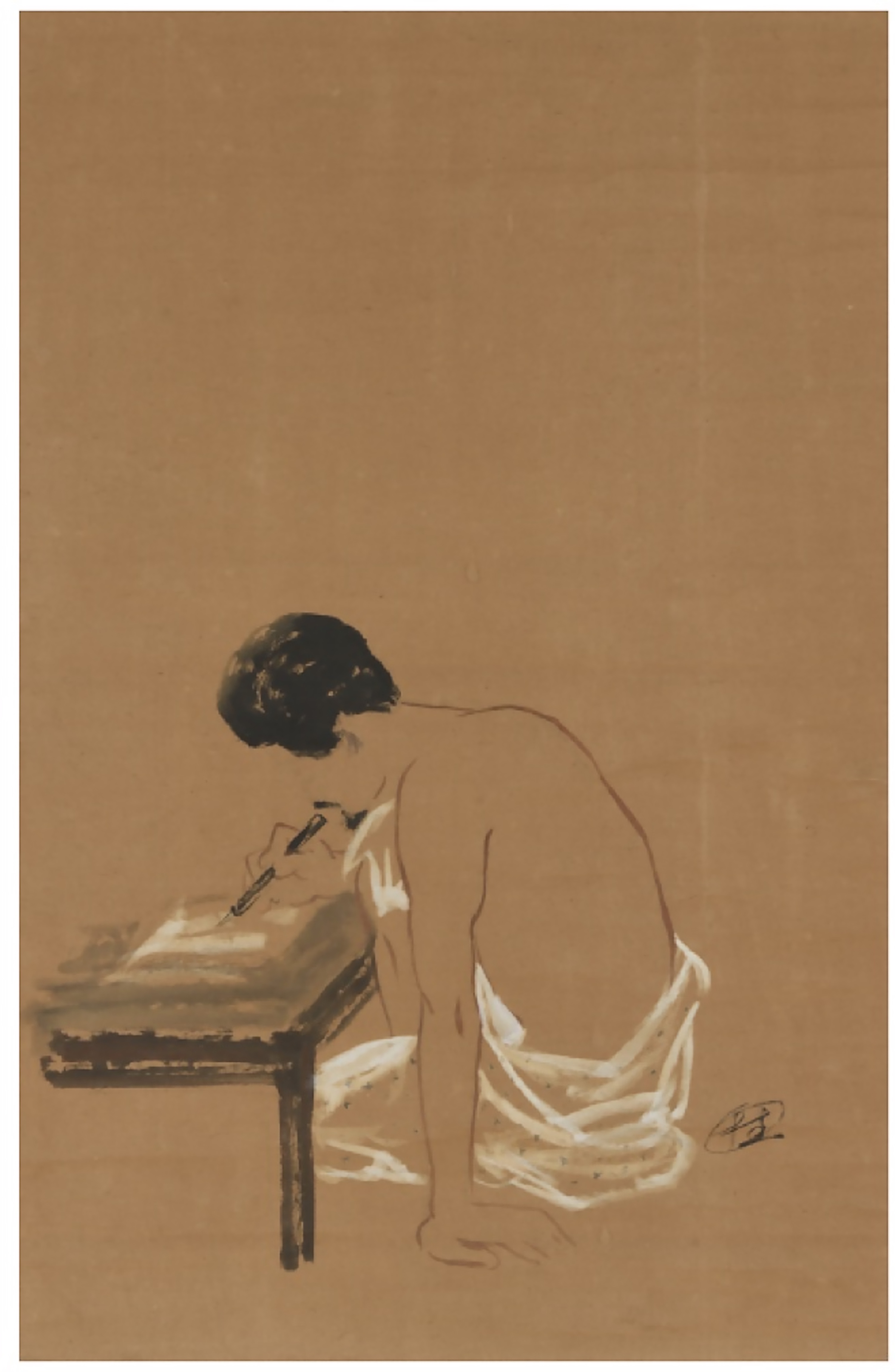

It seems that these great personal losses moved Mochizuki to step back from the anarchist movement. At the end of the 1920s, he joined the Yomiuri Shimbun, one of Japan’s main daily newspapers, as a cartoonist. Due to his past, he was obliged to use a pseudonym, Bontaro Saikawa, a name he returned to a decade later when he launched a raucous manga titled Bakusho, every issue of which is displayed here. Its inaugural issue saw a collaboration with Mochizuki’s one-time art-school classmate, Tsuguharu Foujita, who had returned to Tokyo having befriended—and, at least apocryphally, outsold—Picasso in Paris (and who was soon to become Japan’s leading war artist). As the Second Sino-Japanese War teetered into world war, Bakusho folded.

Around 1945, Mochizuki moved back to his hometown in Nagano, where for the next three decades he lived an apparently peaceful life as a popular teacher at a girls’ school and an influential figure in the agrarian reform movement. He continued to paint landscapes, and seems to have left invitations from his former comrades in Tokyo unanswered. The works from this period are sometimes signed as “Peasant Katsura” or under the nom de plume from his newspaper days. Mochizuki dedicated his long life to various forms of collective work: education, publishing, organizing, exhibition-making. But he remained, and remains, both unpredictable and difficult to categorize, always on the move.