April 18–September 15, 2025

Euphoria once signified “wellbeing through endurance,” and although it has come to mean something closer to “intense happiness,” the original undertones persist. The theme of resilience—and how language is flexible and meaning endures—echoes through this major retrospective of Tomaso Binga’s work. Curated by Eva Fabbris and Daria Kahn, the exhibition spans eight rooms and features 120 works, using the word “euphoria” as a bold call to speak, stretch, and persevere.

Binga has worked for six decades as a performer, poet, and visual artist, using language and gesture to expose and undermine patriarchal systems. “Euforia,” which avoids a chronological format so as not to historicize a living artist, includes early drawings and ceramic works from the 1960s inspired by her teaching experiences, while her primary media—paper, cardboard, and photography—document performances mainly from the 1970s. Many of these actions were not filmed, and so what remains are pictures, notes, memories, and an acute awareness of modest, lo-fi materials. Her best-known work—represented here through photographs—also shaped her reputation for subsequent decades. Oggi Spose [Just Married] (1977) shows the artist (given name Bianca Pucciarelli Menna) in a mock wedding to her male alter ego Tomaso Binga: the work mounts a sharp feminist critique of gender roles and women's marginalization in art.

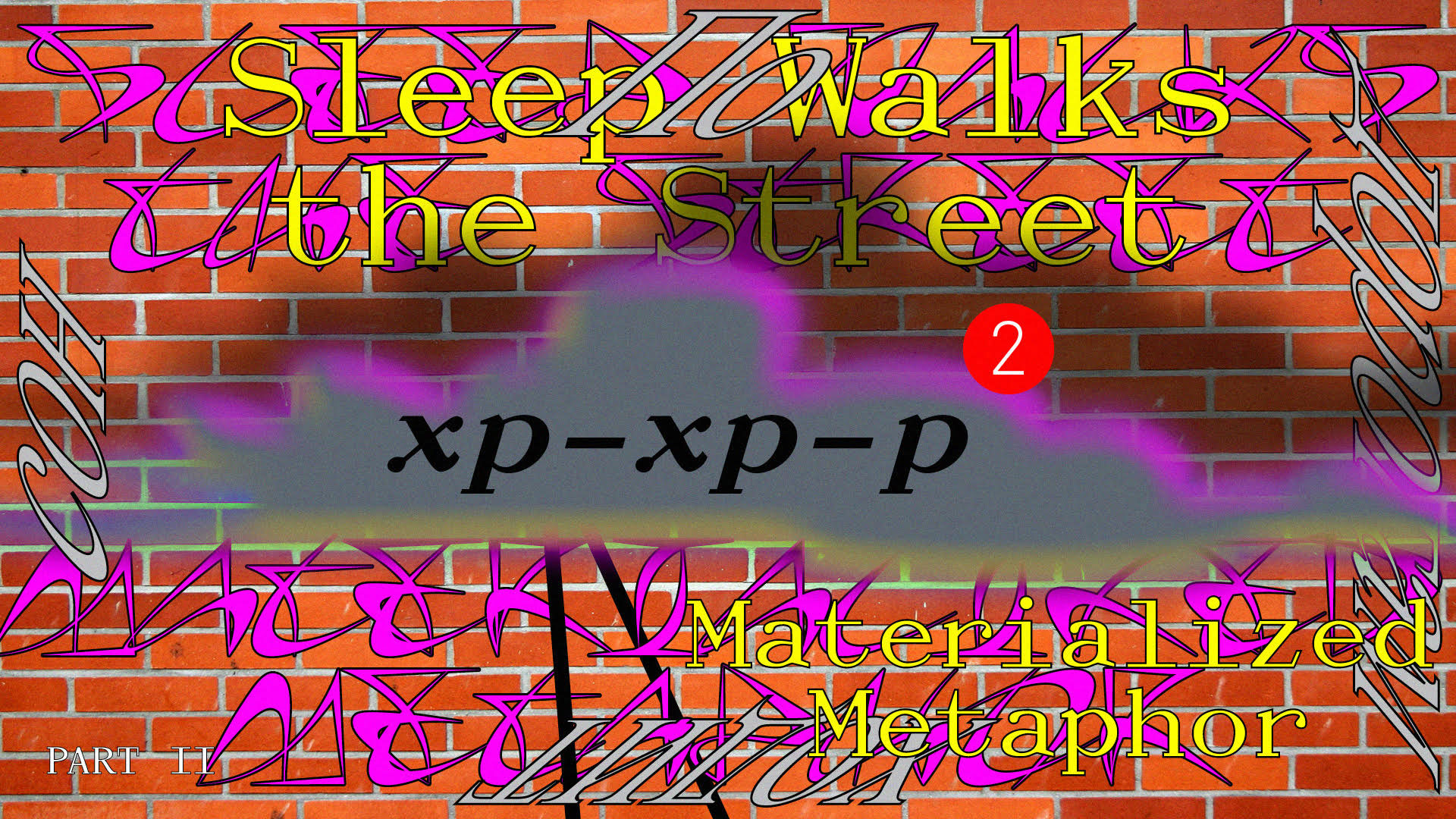

From the outset, the exhibition foregrounds Binga’s use of language as material. The first room features a selection of her most celebrated works, including Io sono io. Io sono me [I Am I. I Am Me] (1977), which is placed next to the “Scrittura Vivente” [Living Writing] (1975) and “Scrittura Desemantizzata” [Desemanticized Writing] (1971–ongoing) series of works. In them, Binga displays handwritten signs—inscribed across panels, notebooks, clothing, and wallpaper—that seek to liberate language from fixed shape or meaning. These works, like others emerging from the Nuova Scrittura [New Writing] movement, demonstrate how doodles and anthropomorphic shapes might transform into letters or fragments of deconstructed language. Some of Binga’s ceramics, shown in a parallel room, display signs of religious imagery: read next to the text-based works, the resonance seems to lie not in dogma but in Binga’s formal engagement with iconography. Similar ideas recur in later works, such as Il confessore elettronico [The Electronic Confessor] (1992), which shows an image of the artist in an ironic prayer pose while wearing a priest’s black garb.

The design of the exhibition, conceived with the multidisciplinary collective Rio Grande, reimagines conventional display methods to better serve an archival and research-intensive show. Avoiding standard wall mounting, the installation features a winding metallic beam that curls and unfurls throughout the space, turning each room into a stage. This playful, tongue-in-cheek structure, developed with the ninety-four-year-old Binga’s input, sometimes suspends works, and at other times guides the viewer physically and visually. Works are not just displayed, here, but elicit a new vitality.

One of the most successful rooms features “Polistiroli” (1971–74), a series of cut-out polystyrene containers originally designed for packaging. Into these voids, Binga inserted magazine clippings of women—images evoking beauty contests, politics, yoga, and self-care. These women appear confined, framed, or in tension with their enclosures. The artist’s friends donated packaging materials, forming what Binga called “affective chains”—an informal participatory process that underscores her collaborative ethos.

In “Euforia,” identity splits and reforms. Embedded in linguistics and semiotics, Binga’s works repeatedly ask: “Am I the object, am I the subject?” In her visual poetry—examples of which are displayed at the end of the exhibition—the artist consistently privileges the feminine; she alters verb conjugations to exclude male forms, introducing what co-curator Kahn describes as “intended errors”—subtle, deliberate disruptions of normative grammar and gender. In its nonlinear format, “Euforia” embraces fragmentation over progression, affect over order.

As such, it refuses closure or resolution. Instead, the show creates space to encounter the artist’s recurring themes: the deconstruction of language, the interrogation of authorship, the tension between subject and object, and a radical embrace of the feminine. For Binga, euforia is not an escape but a declaration of autonomy. It is a form of excess in a world that demands restraint, a feminist assertion of space: linguistic, visual, and bodily.