April 20–September 21, 2025

In a far corner of ILHAM plays Gogularaajan Rajendran’s Coolies’ Chorus (2025), a seventy-minute video in which Indian singers and musicologists coax back into being the tunes once sung on Malay plantations by indentured Tamil workers. Using the posthumously published lyrics and their own expertise in Tamil Nadu’s folk song traditions, the participants attempt to recover the songs’ lost melodic structures, and engage in an often poignant process of informal peer review. “The deceits and tortures they experienced,” remarks one singer, “are all in these songs.”

Rajendran’s simple yet powerful video is among several works in this group show, comprising contributions by twenty-eight artists and collectives, that illuminate the visceral realities of Malaysia’s plantation industry, which emerged during nineteenth-century British rule. Chuah Thean Teng’s landscape painting The Huskers (1980) portrays a lone man in a loincloth, using his body weight to drive a coconut against a pointed stake (the method used to husk coconuts until as recently as 1995, a caption states). In another canvas, a moment of succor disrupts the tedium of a banana plantation: Kuo Ju Ping’s Indian Dancers (1956) shows a group of South Indian women laborers performing a kolattam stick dance, arms aloft and hands swaying.

At another end of the gallery is Izat Arif’s Tuan Tanah (Land Lord) (2025). Ensconced in three obelisk-like structures made from soil are video monitors playing three archival clips related to the Federal Land Development Authority (FELDA), a government agency that began resettling Malaysia’s landless poor into smallholder plantation colonies in 1956, and so helped make the country—as one clip claims—a role model. “You have impressed the entire world with your determination to close the gap between the rich and the poor of your own nation,” says President Lyndon B. Johnson during a visit in 1966. Nearby, another clip suggests that FELDA’s gifting of land to rural settlers was conditional upon their being good citizens (“We human beings are from soil. Thus to the soil we are indebted”).1

This scattered constellation of work serves to center the plantation within Malaysian history—an effect that dovetails with the exhibition’s broader, well-structured goal: to center the plantation within world history. In her 1971 essay about the Caribbean system, “Novel and History, Plot and Plantation,” Sylvia Wynter posits that plantation history is a fiction—a plot authored by the market economy—to be overcome. Invoking Wynter, the wall text opens with a bitter admission of defeat.2 Here, amid the ruins of the “broken world,” inherited artworks corralled from across Southeast Asia and the Americas are positioned much as the literary novel is in Wynter’s essay: as a tool for making the plantation’s master narrative of political economy and human consequences clearer, and for making its “presence strange,” as curator Lim Sheau Yun writes.

Alongside telling the plantation stories of those “planted” in them, this exhibition thickens its plot by highlighting the engineered, uncanny sameness of plantation produce. Corey McCorkle’s Pendulum (2016) comprises a large stalk of Cavendish bananas that, having been tethered to a metal pulley, forms a motionless pendulum above the show’s entranceway: a metaphor for the genetic stasis resulting from the colonial history and cloning of said banana. That the disease-prone fruit will rot over the duration speaks to the pathological perils of monoculture.

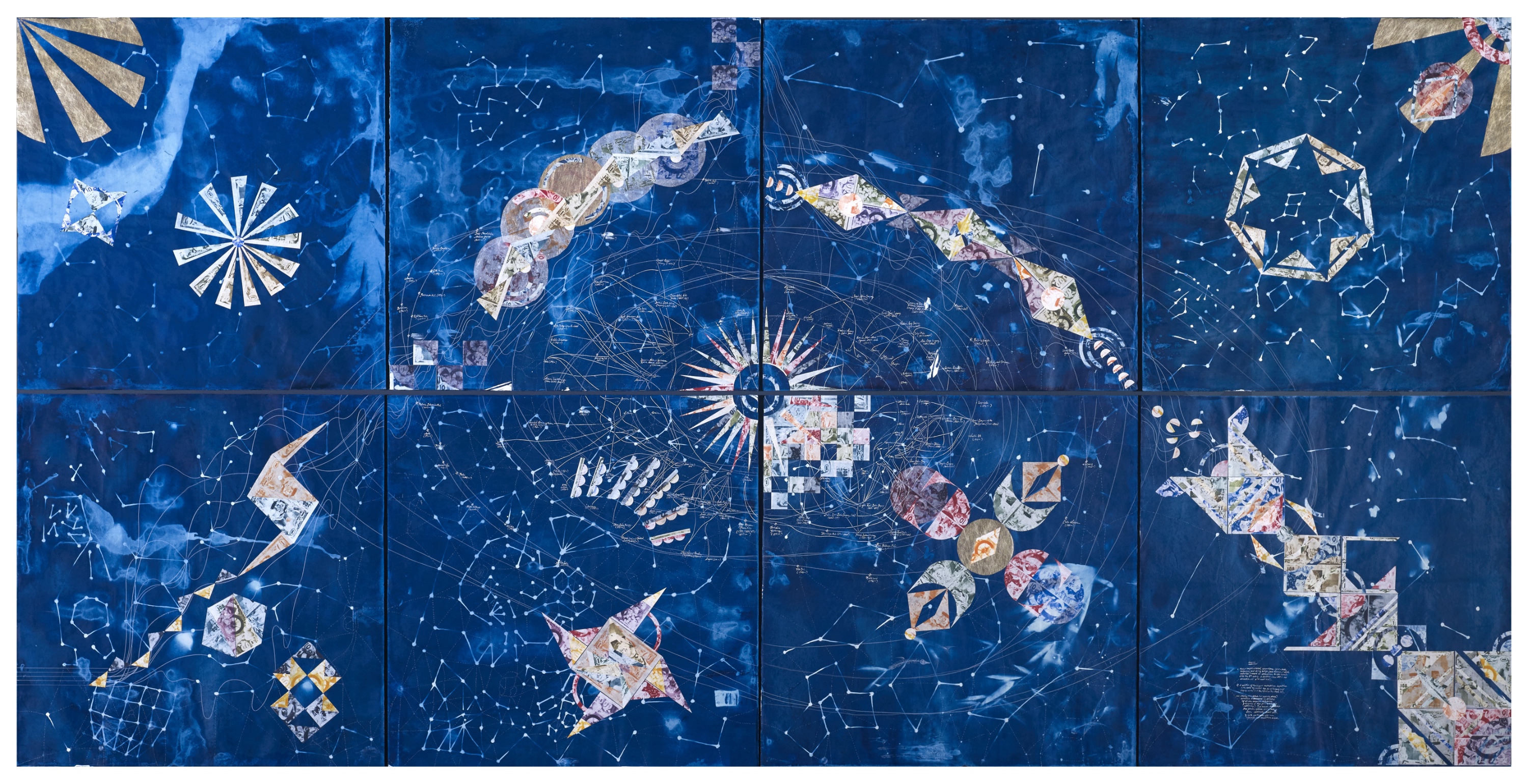

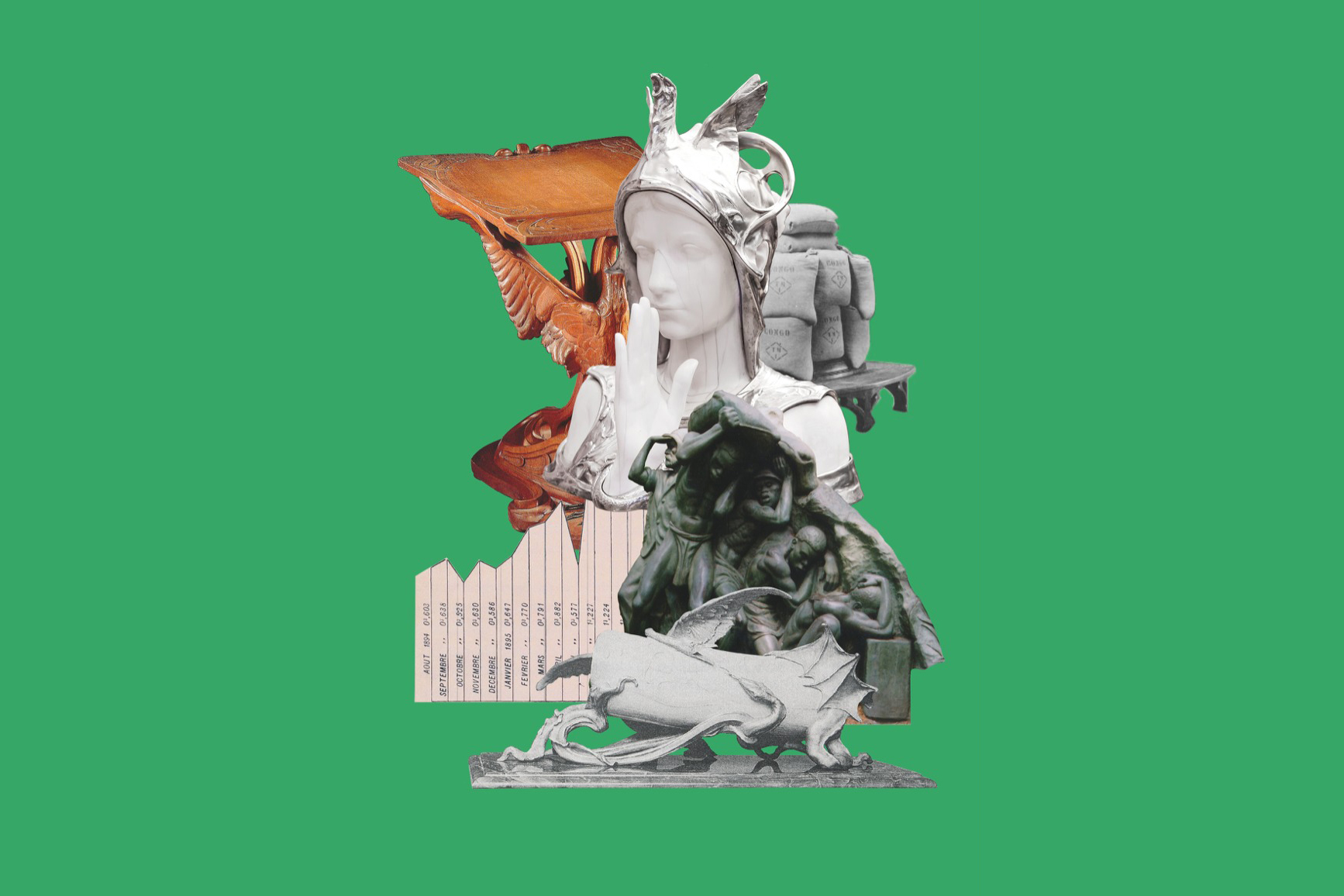

Mounted on opposing walls nearby are a couple of cognitive maps representing the relationship of capital and power with the plantation system. Connie Zheng’s As It Is: Nothing Lasts Forever (2025) charts the linkages between multinationals, joint-stock companies, living beings, crops, and mineral resources traded as commodities since the sixteenth century. Based on ancient Chinese star maps, this gaseous, indigo-blue cosmos—stippled with geometric shapes made from intaglio banknotes and reminiscent of Wassily Kandinsky’s Theosophic abstractions—is dazzling. Conceptually aligning market forces with observable yet baffling celestial events, the work also feels faintly hopeful: the lifelines of many of these corporations peters out into the void. In contrast, Cian Dayrit’s fabric piece Semi-Feudal Order (2025), a digital print of a colonial-era image overlaid with a crude embroidered flowchart, draws us into the terra incognita of the repressive land monopoly. Joining its hierarchy of injustices meted out in haciendas and corporate plantations are slogans such as “Agrarian Revolution is Justice.”

Shifting between the past and present tenses, the abstract and the material, “The Plantation Plot” excels at conjuring a colonial ambience, a sense that the themes raised are part of a single, ongoing story. In addition to evoking the longue durée of the plantation, its enduring logic and universality, it also leaves the viewer with an ineffable, and at times searing, sense of how workers of the recent past were segregated along ethnic lines, overworked, and, once no longer productive, disposed of like “sucked oranges.”3 The exhibition is on shakier ground, though, when it comes to the more-than-human aspects of the plantation system. Scant attention is given to the multispecies ethnography that scholars of the “Plantationocene” so passionately endorse—a symptom, perhaps, of the plantation’s all-conquering, destructive supremacy.4

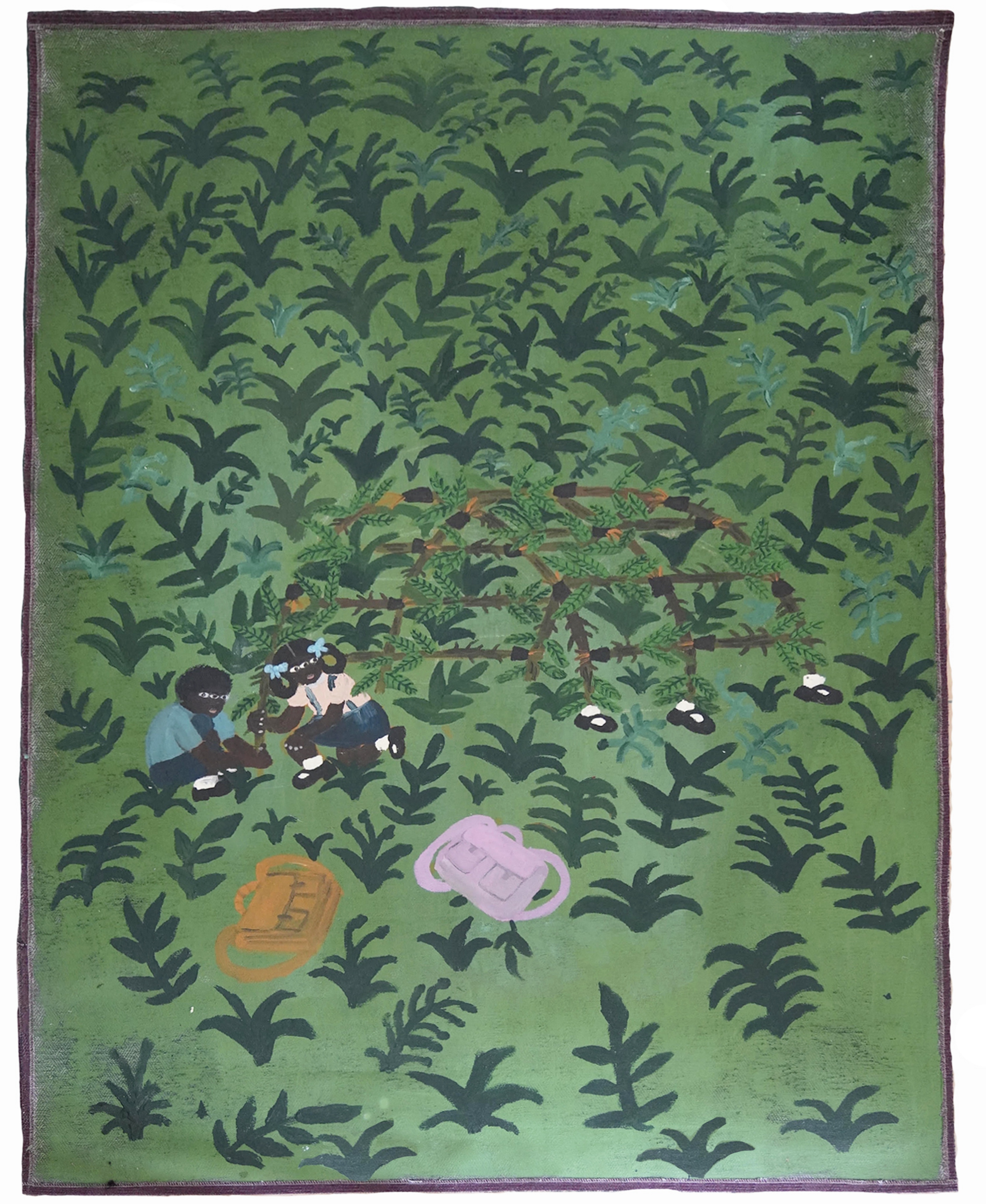

In this context, a couple of counternarratives addressing the affordances and agency of plants and animals feel all the more potent. Injecting some much-needed tenderness into proceedings is Nguyen Phuong Linh’s Memory of the Blind Elephant (2016), an unnerving video work that asks us to sympathize with an elephant chained amid disfigured rubber tree trunks, but the standout works in the “Today will take care of tomorrow” section are the late Inauk S Gullah’s faux-naive paintings, which teem with untrammeled life and rhizomatic abundance. One vividly depicts the thirty-six fruits now extinct due to illegal logging in Sabah (a Malaysian state in northern Borneo); others show weasel-like animals lapping up the blood of a hunter’s kill, or a huntsman traipsing home through wild woods. Most of this exhibition explores what the agricultural plot now is, in both a narrative and a physical sense. In these arboreal paintings, each a lush realm of ecological interdependence, we glimpse what it once was—and could, however unlikely, still be.

Surfacing amid Malaysia’s nascent, postindependence nation-building efforts, this biopolitical sentiment brings to mind Donna Haraway’s comments on the coercive nature of manual farming practices today: “It’s not slavery, but it is the kind of labor force that I associate with plantation conditions.” See “Reflections on the Plantationocene: a conversation with Donna Haraway and Anna Tsing,” Edge Effects and Nelson Institute at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, June 18, 2019, 10.

“The plantation has not merely persisted. It is multiplying under our very noses: in Indonesia and Malaysia, millions of hectares of forests and farmland have been cleared to plant oil palm. If we pull back the lustre of the corporation, what remains is a lumbering and inefficient colossus, profound in its banality and profoundly banal. The plot is written in the horizons of oil palm that line our highways, the gutta percha rubber that fills our root canals, the fruits we buy from the grocery store.” Wall text, ILHAM.

The genealogy of the phrase “sucked oranges” was discussed in May at an exhibition talk at ILHAM on colonialism, class, and caste in plantations with Malaysian economist Professor Jomo K. Sundaram, moderated by Ong Kar Jin. See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xn4POIIOg08. It is also the title of a 1989 anthology, Sucked Oranges: The Indian Poor in Malaysia.

The term “Plantationocene” is used by some scholars to refer to our current geological epoch. By grounding the alteration of landscape in histories of colonialism and plantation agriculture, not the universal agency of humankind, it seeks to evade the imprecision of the more prevalent “Anthropocene.”