January 21, 2015, 12am

Artists: Alina and Jeff Bliumis, Chto Delat, Keti Chukhrov, Anton Ginzburg, Pussy Riot, Anton Vidokle, Arseny Zhilyaev

Curated by Boris Groys

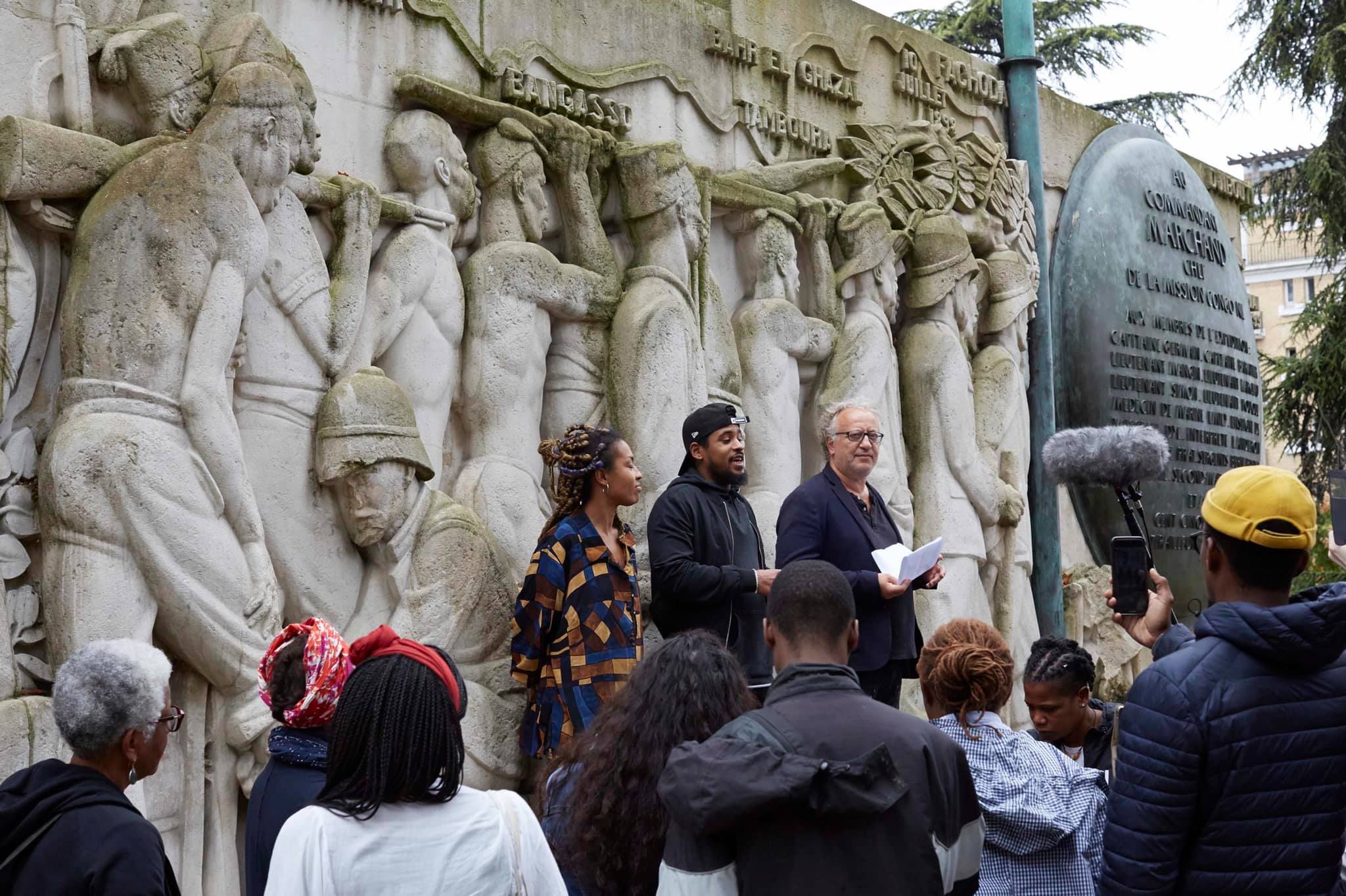

Contemporary Russian artists are still haunted by the specters of communism. On the one hand, they do not want to close the utopian perspective that was opened by the October revolution and art of the Russian avant-garde. But, on the other hand, they cannot forget the long history of post-revolutionary violence, where artists are haunted by these specters in the middle of reality that does not welcome them.

In contemporary Russia in which the official political and cultural attitudes become increasingly conservative, a new generation of Russian artists continue the tradition of the Russian artistic and political Left: desire to change the reality by means of art, ideals of equality and social justice, radical Utopianism, secularism and internationalism. This exhibition includes the works of artists from Moscow and St. Petersburg who share a critical attitude towards the realities of contemporary Russian life.

Pussy Riot address the power of the Church and its complicity with the state. The group’s famous “Punk Prayer” brought two of its members into prison. The videos of Chto delat thematize the cultural and political issues with which the Left is confronted in the contemporary world. Arseny Zhilyaev supplies an ironical commentary to the contemporary Russian media space in which the sensational news about UFOs and meteorites circulate together with Putin’s quasi-artistic actions, like kissing the tiger and finding the antique amphorae at the bottom of the sea. And in her poetic and poignant video Keti Chukhrov shows the gap between the intellectual attitudes of the Russian leftist activists and their real social behavior.

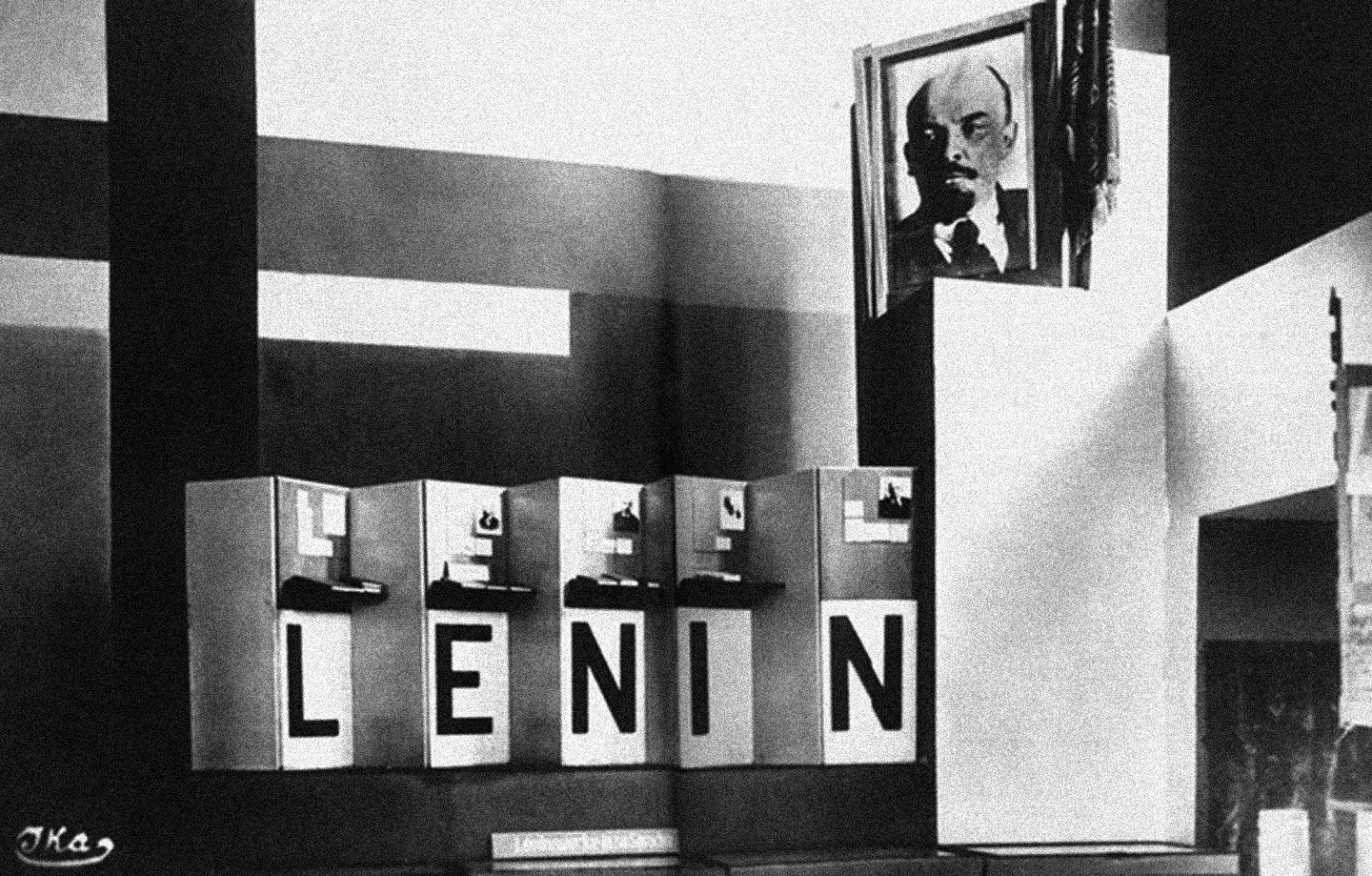

The exhibition includes the works of New York artists of Russian origin who also deal with the heritage of Russian communism. Anton Vidokle rediscovers in his works the radical Utopian projects of the Russian political and artistic avant-garde aiming at creating the world in which men become immortal and at the same time re-united with cosmic life. Anton Ginzburg finds the traces of the gigantic “earthworks” of the Soviet time. And Alina and Jeff Bliumis nostalgically try to reestablish the direct contact with the audience that was lost by art under the conditions of the art market.

Alina and Jeff Bliumis’s work concerns the politics of community, cultural displacement, migration and national identity. Jeff and Alina began their collaboration in 2000. Their work has been exhibited at Denny Gallery, Laurie M. Tisch Gallery, Bronx Museum of the Arts, New York, as well as internationally at Centre d’art Contemporain in Meymac, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, among others.

Keti Chukhrov has authored numerous publications on art theory, culture, politics and philosophy. Her books include To Be—to Perform, Just Humans, and Pound & £—the first in Russian dedicated to Ezra Pound’s works, investigating the interrelation between poetics and politics.Her play, Afghan Kuzminki, was featured at Theatre.doc, in the 2011 Moscow Biennial, and at the Wiener Festwochen in 2013. She most recently participated at the Bergen Assembly by showing her latest video-play, Love Machines. Chukhrovis Associate Professor at the Russian State University for Humanities.

Chto Delat (What is to be done) is a self-organized platform for a variety of cultural activities intent on politicizing knowledge production through redefinitions of an engaged autonomy of cultural practice. The collective’s public debut took place on May 24, 2003, in an action called “The Refoundation of Petersburg,” a response to the 300th anniversary of the city. The still nameless core group then began publishing an international newspaper called Chto Delat?. The name is inspired by an eponymous novel by Nikolai Chernyshevsky about the first Russian socialist workers organizations, and a political pamphlet published in 1902 by Vladimir Lenin.

Anton Ginzburg uses an array of historical and cultural references as starting points for his investigations into art’s capacity to penetrate layers of the past and reflect on the contemporary experience. He has been shown at the first and second Moscow Biennales and the 54th Venice Biennale, as well as the Blaffer Art Museum at the University of Houston, the Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, and the Palais de Tokyo, among others. He is represented in the permanent collections of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Moscow Museum of Modern Art, as well as private collections around the world.

Pussy Riot is a collective of artists and activists. In August 2012, two of its founding members, Nadezhda (Nadya) Tolokonnikovaand and Maria (Masha) Alekhina, were imprisoned following an anti-Putin performance in the Moscow Cathedral of Christ the Saviour and were released in December 2013. In March 2014, the pair announced the opening of the Mordovia office of Zona Prava (Zone of Rights), their organization advocating for transparency and humane conditions within the Russian justice system. The following September they launched their independent news service, Mediazona, which focuses on courts, law enforcement, and the prison system in Russia. Tolokonnikova and Alekhina are the 2012 recipients of the LennonOno Grant for Peace.

Anton Vidokle has most recently exhibited works in the 2014 Montreal Biennale and the 10th Shanghai Biennale. As a founder of e-flux he has produced Do it,Utopia Station poster project, and organized An Image Bank for Everyday Revolutionary Life and Martha Rosler Library. Other works include e-flux video rental and Time/Bank, co-organized with Julieta Aranda; and Unitednationsplaza—a twelve-month experimental school in Berlin as a response to the unrealized Manifesta 6. From 2013–14, Vidokle was a Resident Professor at Home Workspace Program, organized by Ashkal Alwan in Beirut. Vidokle is co-editor of e-flux journal along with Julieta Aranda and Brian Kuan Wood.

Arseny Zhilyaev is an artist who proposes new approaches to the tradition of Soviet museology. This has been a recurrent theme amongst his recent artistic projects, such as Museum of Proletarian Culture: Industrialisation of Bohemia, Tretyakov State Gallery, Moscow, 2012; M.I.R.: Polite Guests from the Future, Kadist Art Foundation, San Francisco and Paris, and others.

Boris Groys is a Global Distinguished Professor of Russian and Slavic Studies at New York University and Senior Research Fellow at the Karlsruhe University of Arts and Design in Karlsruhe, Germany. Groys was curator of the Russian Pavilion at the 54th Venice Biennale and of “Total Enlightenment: Conceptual Art in Moscow” 1960–1990, among other exhibitions. His recent publications include History Becomes Form: Moscow Conceptualism, Going Public, Art Power, and Ilya Kabakov: The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment.