[columns]

Convened by

Cao Fei

With films by Fei Yining and Chuck Kuan, Yong Xiang Li, Xin Liu, Zhang Congcong, Haonan Wang, Zheng Yuan; and interviews with the filmmakers by Emma Enderby, Cao Fei, Alvin Li, Lawrence Xiao, Evonne Jiawei Yuan, and Yang Beichen

*Crashing into the Future wraps on Monday, April 5 with a repeat screening of all six films presented in the program.

Various signs around us suggest that we have reached a moment where the contradictions accumulated by our history can no longer be sustained. A sense of déjà vu takes hold. Once again, the uneasy organisms of this planet look up and gaze at the cosmos as they hastily crash into the future...

For this program, I've selected works by video artists from China born in the late 1980s and 1990s. Most of the featured artists studied or lived abroad for some time, and their artistic practices reflect their diverse influences. I have attempted to delineate thematic junctions in their works that, together, constitute a kind of rhizome wherein meaning is produced in the space between the nodes.

1. Monstrosity

Contemporary culture is rife with the figures of ghosts, aliens, chimeras, cyborgs, undead, zombies, and other indescribable organisms and hybrid species. Sometimes these “monsters” are friendly, other times decidedly not. They could be passersby, or our partners; they might even be us. In essence, their stories are fables of humankind’s contradictions—both inner contradictions and contradictions with the world. If these monsters mirror our alienation, they also mirror our transformation, and sometimes our emancipation.

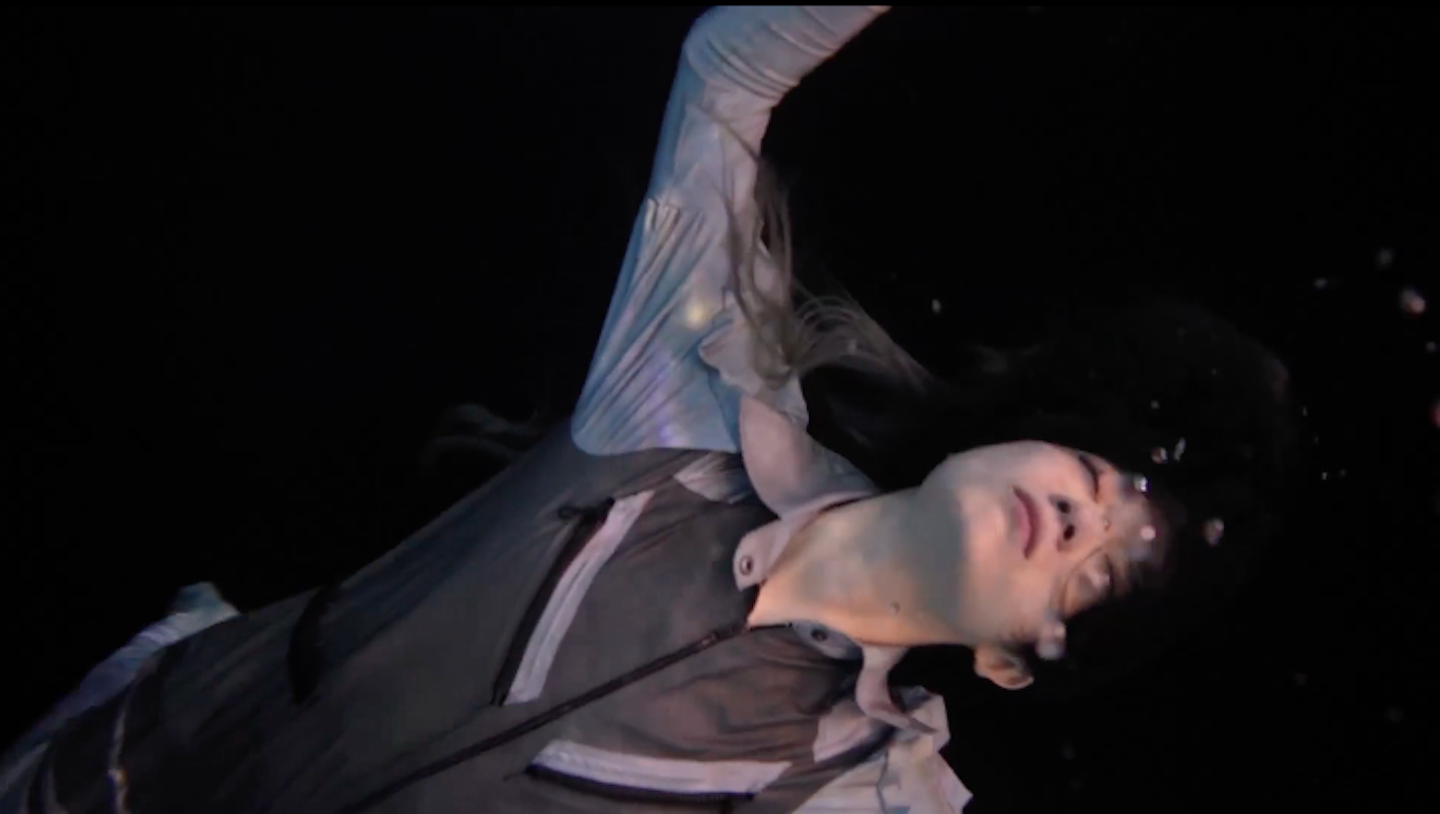

Made during the pandemic in 2020, Yong Xiang Li’s I’m Not in Love (How to Feed on Humans) features the artist himself as a vampire in search for more than just everlasting life. Partly a playful take on contemporary relationships, the video is also a last celebration of vampirism in a seemingly apocalyptic time. In Haonan Wang’s Bubble (2020), foliage sprouts out of and consumes the male protagonist, transforming him into a beast to be consumed in turn by his female lover. Human and beast, desire and hunger, consumer and food become indistinguishable in a cathartic culmination of alienation..

2. Ghost Worker

The New China of post-1949 witnessed an intense drive to shape the image of the worker, with poetry, music, painting, sculpture, and film devoted to celebrating and enshrining the working class. Since China’s economic reforms of 1978, however, the relationships between various social classes in China have been dramatically transformed. With the identity of the worker ruptured and reconstituted, the working class gradually disappeared from political rhetoric—a phenomenon most significant amid the rapid development that globalization wrought on China in the 1990s. Today, the internet service sector spawned by the new economies of artificial intelligence in China has grown into a “labor-intensive” industry. This industry has given rise to food delivery workers, couriers, app-hailed drivers, and various kinds of door-to-door occupations. “Digital labor” gradually became unstable and isolated, a competition of speed between invisible bodies—ghost workers.

Zhang Congcong’s Element (2021) focuses on the relationship between capital and labor, as well as the corporeality of production. In Element, workers don their machine-operator uniforms and go on long, aimless walks by the sea. They take in the ocean breeze and bask in the sun, reminiscent of the leisurely middle-class figures of Georges Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884-86). They are connected by a string of vague actions that can’t quite be called work. Here, Zhang deconstructs the legitimacy of labor and empties its content. Stage after stage, the production chain recalls a mysterious ritual, a whispered code. Zheng Yuan’s Dream Delivery (2018) depicts a group of motorcycle couriers dressed in colorful uniform. The camera pushes and pulls, and pans over them as though in a commercial shoot. Against a backdrop alternating between pastoral park and desert of ancient ruins, they bask in the resplendent sun or fall onto the ground in intoxicated bliss. Through the juxtaposition of interviews, documentary footage, and fiction, the film encapsulates the lived realities of this new type of worker, whose vulnerable body attempts to elude the manipulations of invisible hands.

3. Cosmos in Flux

Philosophical efforts to transcend human limitations and reform the universe—such as those proposed by Russian cosmism or transhumanism—have already become part of an approaching quotidian. Many technologies bear humankind’s insistent belief in transformation and enhancement, and bid farewell to the body, while information becomes the medium by which we consciously intervene in the universe.

Artists Fei Yining and Chuck Kuan’s Breakfast Ritual: Art Must Be Artificial (2019) fades out the human as subject and exhibits a free consciousness dominated by AI, floating in a sea of fragmented memories after stellar cooling, passing through an incorporeal whisper of a dream. Is this the eve of the awakening of AI ideology? If the body can be seen as a proxy, then Xin Liu’s Living Distance (2019-20) removes a tiny part of the body—a wisdom tooth—and sends it into space. The wisdom tooth becomes the protagonist of a melancholy trip around the cosmos, reprising the role of the Soviet space dog Laika. The symbiotic relationship between the physicality of the wisdom tooth and the boundlessness of the universe seems to pay homage to the immortality and eternity sought in cosmism.

—Cao Fei, translated by Mike Fu

Crashing into the Future is a program convened by Cao Fei as the fifth cycle of Artist Cinemas, a long-term, online series of film programs curated by artists for e-flux Video & Film. Crashing into the Future will run for six weeks from February 22 through April 5, 2021 screening a new film each week accompanied by an interview with the filmmakers(s) conducted by Cao Fei and invited guests.