Rodrigo Roa Duterte, “Speech at Meeting with Local Chief Executives,” Pasay City, February 10, 2020.

My reading of this is indebted to Rosalind C. Morris. See her “Populist Politics in Asian Networks: Positions for Rethinking the Question of Political Subjectivity,” positions 20, no. 1 (Winter 2012): 37–65.

On the constitutive role of files in administration, see Cornelia Vismann, Files: Law and Media Technology, trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young (Stanford University Press, 2008).

This is also what fundamentally distinguishes populist demagoguery from the monumental governmentality of Latin American republicanism or the authoritarian populism some have identified with Thatcherism, both of which partake in the politics of the figure in order to enrich institutional power. That said, if there is an organ of the state that excites the populist demagogue, it is the police—not because the police instantiate the rule of law but because the physical act of policing provides the referent for the populist demagogue’s claim to directly fix society’s problems through his personal force. On the monumental governmentality of Latin American republicanism, see Rafael Sánchez, Dancing Jacobins: A Venezuelan Genealogy of Latin American Populism (Fordham University Press, 2016). On authoritarian populism and Thatcherism, see Stuart Hall et al., Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order (Macmillan, 1978).

Aaron Schuster, “Primal Scream, or Why Do Babies Cry?: A Theory of Trump,” e-flux journal, no. 83 (June 2017) →.

Sánchez, Dancing Jacobins, 145, 259, 290.

One of the first mentions of the “turbulent fifties and early sixties” was in a 1982 speech by then–minister of health and future prime minister Goh Chok Tong. See his “Speech at the Quarterly Luncheon of the General Insurance Association of Singapore,” Singapore, March 10, 1982.

Rene Niehus et al., “Estimating Underdetection of Internationally Imported Covid-19 cases,” medRxiv, February 14, 2020.

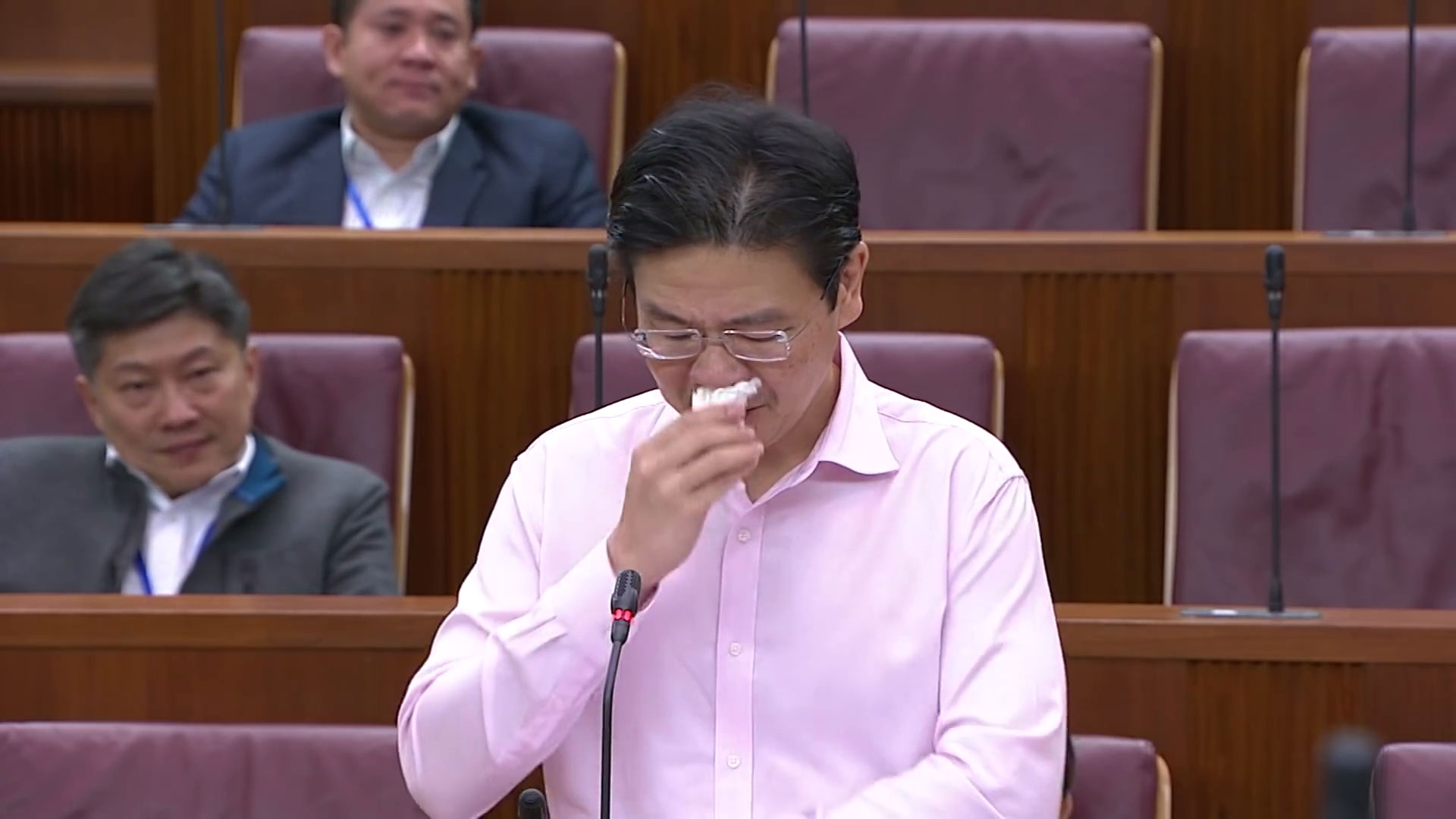

Lawrence Wong, “Speech at the Multi-Ministry Taskforce on Covid-19 Press Conference,” Singapore, March 31, 2020.

Wong, “Speech at the Multi-Ministry Taskforce on Covid-19 Press Conference,” Singapore, April 3, 2020.

The measures that proved the most decisive in Taiwan, one of the countries often brought up as an exemplar of the liberal-democratic approach, were early travel bans, strict quarantine policies, and consolidation of production lines for face masks—not exactly what you would find in the liberal playbook. Meanwhile, in Vietnam, the relative transparency of public data compared to neighboring China has been crucial in allowing the country governed by a one-party state to emerge from their lockdown without any fatalities. See Hsien-Ming Lin, “Lessons from Taiwan’s Coronavirus Response,” East Asia Forum, April 2, 2020; and Minh Vu and Bich T. Tran, “The Secret to Vietnam’s Covid-19 Response Success,” The Diplomat, April 18, 2020.

As poet and playwright Alfian Sa’at expressed in a pithy remark made on Facebook: “For things like ‘pesky’ activists, the government uses sledgehammers, but for things like an actual pandemic where actual lives are at risk, they’re trying to use flyswatters.”

Dewey Sim and Kok Xinghui, “How Did Migrant Worker Dormitories Become Singapore’s Biggest Coronavirus Cluster?” South China Morning Post, April 17, 2020.

Some studies on the rise of the technocratic class within specific national contexts include Garry Rodan, The Political Economy of Singapore’s Industrialization: National State and International Capital (Palgrave Macmillan, 1989); Hong Yung Lee, From Revolutionary Cadres to Party Technocrats in Socialist China (University of California Press, 1991); and Timothy Mitchell, Rule of Experts: Egypt, Techno-Politics, Modernity (University of California Press, 2002).

Lee Kuan Yew, “Speech at Queenstown Community Centre,” Singapore, August 10, 1966.

Augustine Low, “To Be One Step Behind Is to Be One Step Closer to Disaster,” The Online Citizen, April 17, 2020 →.

Lee, “Speech at Meeting with Principals of Schools,” Singapore, August 29, 1966.

Lee, “Speech at Queenstown Community Centre.”

Lee, “Speech at Queenstown Community Centre.”

Socialism That Works … The Singapore Way, ed. C. V. Devan Nair (Federal Publications, 1978). For an account of the events leading up to PAP’s resignation from the Socialist International and the publication of this book, see Leong Yew, “Relocating Socialism: Asia, Socialism, Communism, and the PAP Departure from the Socialist International in 1976,” in Dynamics of the Cold War in Asia: Ideology, Identity, and Culture, ed. Tuong Vu and Wasana Wongsurawat (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 73–92.

Goh Keng Swee, “A Socialist Economy that Works,” in Socialism That Works, 78.

Goh, “A Socialist Economy that Works,” 83–4. For an account of how the state’s public housing inscribed homeowners within the wage economy, see Loh Kah Seng, Squatters into Citizens: The 1961 Bukit Ho Swee Fire and the Making of Modern Singapore (NUS Press, 2013).

This also explains the government’s choice of the circuit breaker metaphor. More recently, health minister Gan Kim Yong, in speaking of the phased reopening of the economy at the end of the circuit breaker, compared the process to how, with actual circuit breakers, we have to turn on the switches “slowly, one by one,” in order to locate the source of the electrical fault. Gan Kim Yong, “Speech at the Multi-Ministry Taskforce on Covid-19 Press Conference,” Singapore, May 19, 2020.

See →.

Temasek Holdings has a portfolio valued at US$230 billion, while the amount of reserves managed GIC has been stated to be “well over US$100 billion.” In addition, the Monetary Authority of Singapore holds about US$279 billion in foreign reserves. For an account of transparency issues surrounding Singapore’s government-linked companies, including Temasek and GIC, see Garry Rodan, Transparency and Authoritarian Rule in Southeast Asia: Singapore and Malaysia (RoutledgeCurzon, 2004), 48–81.

Tharman Shanmugaratnam, “Speech at PAP Rally for Bukit Panjang SMC,” Singapore, September 5, 2015; and Tharman, “Speech at PAP Rally for East Coast GRC,” Singapore, September 9, 2015.

Mitchell, Rule of Experts, 5–6.

Mitchell, Rule of Experts, 287.

Manu Bhaskaran and Linda Lim, “Government Surpluses and Foreign Reserves in Singapore,” Academia SG, May 4, 2020 →.

On the definition of risk as calculable uncertainty, see John Maynard Keynes, A Treatise on Probability (Macmillan, 1921).

For an account and critique of the government’s expansion on public healthcare spending in recent years, see Michael Barr, “Singapore: The Limits of a Technocratic Approach to Healthcare,” New Narratif, April 16, 2020 →.

For a reading of how the Singapore state has sought to manage the successive crises of capital without undermining the logic of capital itself, see Ho Rui An, “Crisis and Contingency at the Dashboard,” e-flux journal, no. 90 (April 2018) →.

Geoff Mann, In the Long Run We Are All Dead (Verso, 2017), 7.

Mann, In the Long Run, 12.

As Mann argues, Keynesians understand the exceptionality of bourgeois liberal society through its historical relationship to revolution. He notes that the specific revolutionary history that produced bourgeois liberalism, namely the French Revolution, is one that allegorizes the potential destruction to civilization posed by revolution, especially when left in the hands of the masses. Insofar as preserving civilization is their primary task, Keynesians thus acknowledge and legitimize this history but seek “to render it unnecessary, to ‘revolutionize’ without revolution.” It follows that only a bourgeois liberal society can sustain what is at once an immanent critique of liberalism and of revolution. See Mann, In the Long Run, 21–3, 85.

Keynes, Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, Volume VII: The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (Royal Economic Society, 2013), 136.

Mann, In the Long Run, 229, 276–7.

Mann, In the Long Run, 333–4.

Keynes, Collected Writings, Volume VII, 20.

Mann, In the Long Run, 228.

See →.

This estimation was made by infectious disease specialist Dr. Leong Hoe Nam during a video interview on May 6, 2020. See →.

Angela Mitropoulos, Contract and Contagion: From Biopolitics to Oikonomia (Minor Compositions, 2012), 60, 213.

Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (University of Chicago Press, 1958), 28.

Mitropoulos, Contract and Contagion, 220.

In Marx’s inimitable description, money “differentiates itself as original value from itself as surplus-value, just as God the Father differentiates himself from himself as God the Son, although both are of the same age and form, in fact one single person.” See Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume One, trans. Ben Fowkes (Penguin, 1976), 256.

Sara Webb, “Temasek’s Chief, Ho Ching, Likes to Take Risks,” New York Times, July 27, 2007.

Both Thailand and Indonesia have cited Temasek as a model for incorporating their state assets as a vast holding company. See Suttinee Yuvejwattana, “Thailand Evokes Temasek as Junta Tries to Revive State Firms,” Bloomberg News, November 24, 2016; and Henny Sender, “Indonesia Looks to Set Up Sovereign Wealth Fund,” Financial Times, December 3, 2019.

Neferti X. M. Tadiar, “Life-Times of Disposability within Global Neoliberalism,” Social Text 31, no. 2 (Summer 2013), 27.

One of Temasek’s most controversial acquisitions was its purchase in 2006 of Shin Corporation, owned by the family of then–prime minster of Thailand, Thaksin Shinawatra. Protests and demonstrations erupted after news broke that the sale was tax-exempt. In 2007, Temasek was ruled to have breached Indonesian anti-trust laws after acquiring a substantial share in Indosat, the country’s second-largest telecommunications company. During the subprime mortgage crisis in the United States, GIC was heavily rewarded after it sold about half its holdings in Citigroup following a bailout agreement reached with the US government in 2009. On the fraught acquisitions of Shin Corporation and Indosat, see Beng Huat Chua, Liberalism Disavowed: Communitarianism and State Capitalism in Singapore (NUS Press, 2017), 101. On GIC’s investment in Citigroup, see Rick Carew et al., “Citi Bailout Also Bails Out Singapore Fund,” Wall Street Journal, September 23, 2009.

Mitropoulos, Contract and Contagion, 221.

Danson Cheong, “Parliament: About Half of Dorm Operators Flout Licensing Conditions Each Year, Says Josephine Teo,” Straits Times, May 4, 2020.

For a detailed study on the political economy of low-wage migrant labor in Singapore, see Stephanie Chok, “Labour Justice and Political Responsibility: An Ethics-Centred Approach to Temporary Low-Paid Labour Migration in Singapore” (PhD diss., Murdoch University, 2013).

Rosalind Morris, “Intimacy and Corruption in Thailand’s Age of Transparency,” in OffStage / On Display: Intimacy and Ethnography in the Age of Public Culture, ed. Andrew Shryock (Stanford University Press, 2004), 225–43.

Daniel P. S. Goh, “The Little India Riot and the Spatiality of Migrant Labor in Singapore,” Society & Space, September 8, 2014.

This was proposed by Yeoh Lam Keong, the former chief economist of GIC, during a video seminar on April 26, 2020. See →.

Tadiar, “Life-Times of Disposability,” 23.

As David Harvey, among others, has argued, the postmodern aversion towards representationalism on the assumption that it reconstitutes totality is exactly what feeds into capitalism’s totalization of social life. The task at hand is to understand capital not as a thing, but as a dynamic process of creative destruction, and one can only do so through a representational project that accounts for its internal relations without reducing them to a fixed totality. See David Harvey, The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change (Blackwell, 1989), 338–45.

I would like to thank Arlette Quỳnh-Anh Trần, Zian Chen, Kathleen Ditzig, Tan Biyun, Kenneth Tay, Brian Kuan Wood, and Vivian Ziherl for their comments that have helped to clarify my thinking for this essay.