February 11, 2012, 12am

Adam Curtis is not an artist, but a television journalist. Over the last decade, many artists have become interested in his work. Because of this, e-flux and Hans Ulrich Obrist have decided to create a solo show of Adam Curtis’ films—February 11–April 14, 2012―that will include most of his work from 1989 to the present day.

In our current age of uncertainty, both art and journalism are struggling in their different ways to make sense of the present time. This exhibition of Adam Curtis’ works aims to try and break down the divide between art and modern political reportage, to open up a dialogue between the two.

Since the early 1990s Adam Curtis has made a number of serial documentaries and films for the BBC. They are linked through their interest in using the fragments of the past—recorded on film and video―and reassembling them to try and make sense of the chaotic events of the present.

The last twenty years has seen the collapse of many of the grand narratives that drove the world since the Second World War. TV journalism has changed as well, with reporting on events around the world now arriving to us as avalanches of recorded moments, yet carrying little comprehension of what the events mean. Reality slips in and out of focus, much as a fever grips the human mind.

In response to that, Adam Curtis’ films go back into the recent past to tell dramatic stories that lead the viewer to look again at the present day, to help make sense of it. The films are playful with images from the past, mixing journalism with a wide range of avant-garde filmmaking techniques. They also borrow from trash pop and are sometimes silly―but they are also deadly serious in their desire to break through some of the dangerous myths that today’s “avalanche journalism” has created in the modern sensibility. These are myths that those in power attempt to exploit in order to maintain their status at a time when their influence is in decline.

The old idea was that the heart of power was primarily located in the realm of politics. Adam Curtis’ films challenge that notion head-on by demonstrating how power really works in today’s complex society, how it also flows through all sorts of other areas: through science, public relations and advertising, psychology, computer networks, and finance and business.

The show will include these films:

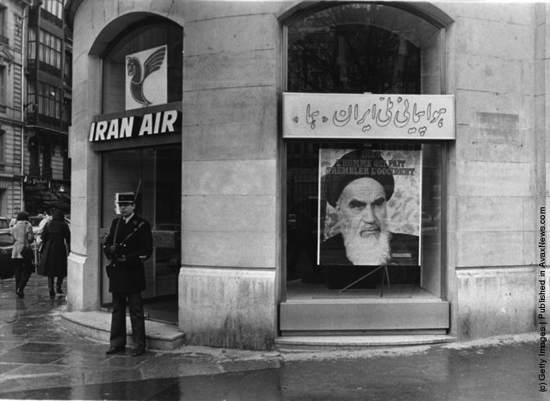

THE ROAD TO TERROR (1989)

An imaginative and playful film which tells the story of two revolutions nearly two hundred years apart―the Iranian Revolution of 1979 and the French Revolution of 1789―and how and why they went in their different ways down the road to terror.

PANDORA’S BOX―SIX FABLES FROM THE AGE OF SCIENCE (1992)

Six one-hour films that together tell the story of how the dream of science possessed politics in the twentieth century. From the RAND Corporation in America in the Cold War―which believed that scientific rationality could manage nuclear apocalypse, to the rise of modern economics―which believed that the rational management of the flows of money in the system could produce heaven on earth. The series shows how science was distorted and corrupted by those in power who asked it to do something it was incapable of doing―making the exercise of power rational.

THE LIVING DEAD—THREE FILMS ABOUT THE POWER OF THE PAST (1995)

This series tells three different stories that together examine how the powerful stories modern societies tell about themselves are constructed—and what is left out and why. The first film is very relevant to today because it tells how the myth of the Second World War that still possesses America and Europe was created—the belief that because it was a Good War it means we are good people. This is the simplistic vision of the world as divided between Goodies and Baddies, a vision that has been used to justify the interventions in Iraq and Libya. But we have forgotten the more complicated bits that had been left out of the story.

THE WAY OF ALL FLESH―THE STORY OF THE UNDEAD HENRIETTA LACKS AND HER IMMORTAL CELLS (1997)

A documentary made in 1997 about the extraordinary story of Henrietta Lacks and the discovery of her cancerous, yet “immortal” cells. It is told with the help of her family.

THE MAYFAIR SET―FOUR FILMS ABOUT THE RISE OF BUSINESS AND THE DECLINE OF POLITICAL POWER (1999)

Four one-hour films that tell the story of a group of men who met in a gambling club in London’s Mayfair in the 1950s, and how they ruthlessly set out to smash through the cozy partnership of the old British political establishment. In the process, they reawakened the markets, destroyed the traditional management of corporations in America and Britain, and helped create the modern global financial world.

THE CENTURY OF THE SELF (2002)

Four films about how Sigmund Freud’s ideas about the human mind were taken and used to manage the world through advertising, public relations, and politics―in turn bringing us the modern world of hyper-consumerism. Out of this came the idea that would dominate politics in the age of the masses―that the dangerous desires and irrational impulses of individuals could be managed on a large scale by objects that reflected and fulfilled those desires: consumer goods.

THE POWER OF NIGHTMARES (2004)

Three films about the rise of the politics of fear. The films tell the parallel stories of two conservative but revolutionary movements―neoconservatism and modern Islamism. How over the past 50 years they grew up separately, but together, they have unwittingly created today’s climate of apocalyptic fear of the future. The films challenge the dark conspiracy theories of our time and show how politicians simply stumbled on that mood of fear, and then tried to use it to restore their declining power and influence. In the process they inflated that apocalyptic mood even further―and allowed it to run out of control.

THE TRAP―WHAT HAPPENED TO OUR DREAM OF FREEDOM (2007)

Three films that tell the story of the rising belief over the past thirty years that the free market could be applied to all areas of human and social life―and how out of that would be born a new utopia of freedom. The films were made just before the present economic crisis, and argued that this vision of freedom is not only limiting, but had become a terrible trap.

IT FELT LIKE A KISS (2009)

An experimental film―all cut to music―that was at the center of an immersive theatre show made in collaboration with the theatre group Punchdrunk. It is about the years 1958 to 1967, the period of America’s rise to global power. It shows how the seeds of today’s uncertainty and lack of confidence about the future can be found hidden in the fragments of film from that period. The very thing that made America unique and powerful―the belief in free individualism―can, in an age of uncertainty, make you feel weak and powerless.

ALL WATCHED OVER BY MACHINES OF LOVING GRACE (2011)

Three films that challenge the present utopian dreams about computers, and the prevalent belief that they can create an alternative networked world where all hierarchies and systems of power will die away. The films show through three different stories how that belief is an illusion―one that, in reality, helps create the very opposite. It reinforces the growing power of today’s unelected elites in the spheres of business, science, and finance.

Adam Curtis is a documentary filmmaker and journalist. He works for BBC television in London. His films have won many awards―including six BAFTAs. His series The Power of Nightmares was invited to the Cannes Film Festival in 2005. Curtis also writes multi-media political and cultural essays on a BBC website using longer sections of film from the archives―www.bbc.co.uk/adamcurtis,

Special thanks to Adam Curtis, Liam Gillick, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Julieta Aranda, Laura Barlow, Brian Kuan-Wood, Joe Pflieger, Alex Poots, Lorraine Two, Anton Vidokle, and Mila Zacharias.

For further information please contact mila@e-flux.com

Screening Schedule

April 14 – PROGRAMME 3

12pm THE CENTURY OF THE SELF (2002): HAPPINESS MACHINES (PART 1)

1pm: THE CENTURY OF THE SELF (2002): THE ENGINEERING OF CONSENT (PART 2)

2pm: THE CENTURY OF THE SELF (2002): THERE IS A POLICEMAN INSIDE OUR HEADS, HE MUST BE DESTROYED (PART 3)

3pm: NOTE: Screenings end to prepare for the closing event.

5pm: Closing Event: Adam Curtis presents a talk interspersed with film footage. A conversation between Hans Ulrich Obrist and the filmmaker will follow.

[audio 120211_adamcurtis]