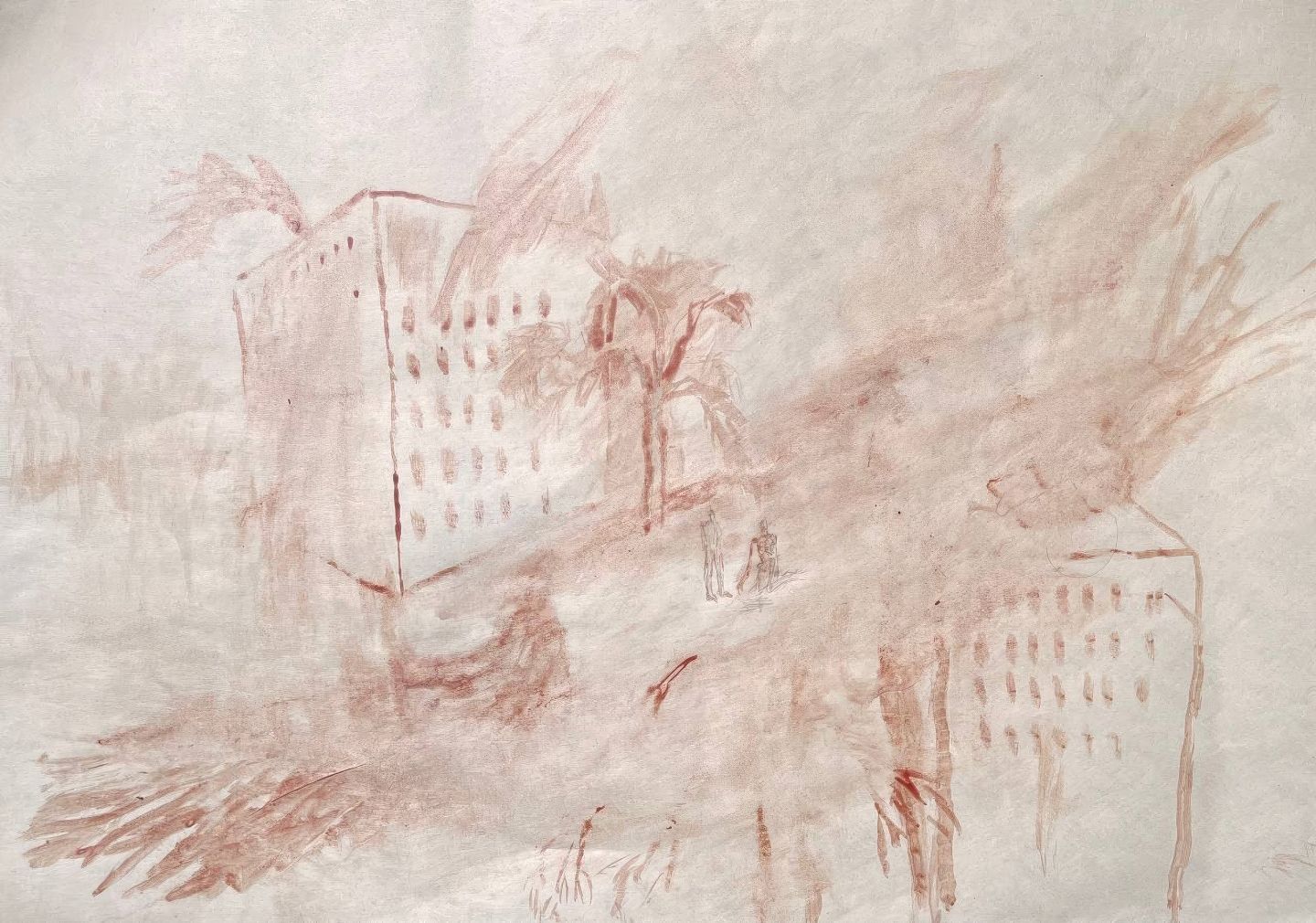

Russian classics. Photo by author.

These days, every statement on the war in Ukraine must be preceded by a disclaimer, namely about geolocation, passport, and alas, blood. I have not lived in Russia for eight years, so I can comfortably condemn the war and Putin’s regime without immediately risking my freedom. But I lived and worked there until 2014, and even if I am not a “Russian curator” anymore (unlike what artnet thinks), I still am a “Russian-born” one; this last part I will not be able to drop ever, as is becoming clear with the war. As the current cultural norm recommends that we “speak for ourselves,” this is what I am doing.

On Facebook, I recently reacted emotionally to the statement that “Russia” bombed the memorial complex at Babyn Yar. I was outraged like millions of other Russians by birth who have all been wanting to scream over the last weeks that this is not the Russia they know and love. So, I wrote that this is Putin’s war, not Russia’s, incurring the justified anger of Ukrainian friends. I of course meant that other, better Russia that doesn’t want Putin, those Russians who are laying low, leaving, and tearing themselves apart over this brutal and delusional war. We all want to say, “This is not us, this is them.” Yet as we are discovering, such differences might not be so important in the face of collective guilt.

Some people blame all Russians—including those long dead—for the current invasion. As Russia is cut off from the global circulation of capital, calls for cultural boycotts are also heard, and some of them make no distinction between this Russia and that. A recent call came from Ukrainian filmmakers (who are completely right to say that many Russian filmmakers, especially big names, have not had the guts, or the desire, to denounce the war publicly). They demanded a “limit [to] the influence of Russian culture in the world,” the culture that, according to them, “has always been an instrument for legalizing all crimes committed and committed by their authorities [sic].”

Calls to boycott all things Russian now are meant to identify Russia with culture, and to target the whole of it as if it were as powerful as her missiles. Ironically, this fetishizing view of Russian culture is also the position of Putinist propaganda, which has become mainstream. It is difficult to grasp what is toxic here: Russian culture per se, or the pedestal it is being put on, positively or negatively. Still, in some ways, the current culture-blaming is a step forward after the war in Yugoslavia, where the West naively insisted on “culture” as a peaceful tranquilizer, not getting that it was precisely highly culturalized and intellectualized narratives of one’s own cultural exclusivity that were feeding the violence.

Russian intellectuals, formerly known as “intelligentsia,” will have to do a lot of critical introspection if we are to understand how we could have supported this criminal regime while protesting against it. One of the issues that many of us have been raising, even before the war, is how wrong the comfortable discourse—still deployed by many in Russia—of “us” vs. “them” is: semi-Asian dirty village idiots who support Putin vs. a “good” Westernized, cultured elite who would of course never do such a thing. This discourse, which erases the responsibility of those who manage to have money (and therefore education), is crashing as we speak, and this makes it even more painful to see it mirrored in some of the current positions about Russia. This is a racialized narrative, much like the one mobilized by anti-communists in the Cold War and earlier, who camouflaged their contempt for anything to the East of them (which could have been different things, geographically) with political and cultural cliches. It plays into Putin’s hands—himself an elitist with an utter disregard for people and their lives.

The ideology that Putin represents is specific, and it has been brewing for a long time: it is the shape of a particular Russian fascism, adapted to a post-Soviet neoliberal age, fed and armed by extractivist global capitalism, not just popular resentment. Just like historical fascism, it seeped into the cultural world too, under the guise of something especially exotic and original. But most of the time it was ignored. My colleagues and I, when I was still working in Russia, were calling it out long ago, when ultra-right-wing artist Aleksey Belyaev-Gintovt got the Kandinsky Prize from Western jury members, among others. That fascist danger, always roaring close by, was one of the reasons many of us, curators and art historians in Russia, me included, abandoned safe academic activities for daily newspapers, online resources, and magazine writing, where we spoke to hundreds of thousands, also those in power. Not many of my Western colleagues would even consider doing this; not their job. I could not afford to say that.

Still, few in Russia wanted to hear it. People didn’t care so much about the fascist drift of the Russian elite, its deep historical roots, its mobilizing maneuvers. It was easier not to listen and to instead fawn over oligarchs’ yachts. What seems so disturbing now is the ease with which countries and economic and cultural institutions blame an entire country and its entire history, just as they previously could easily look away from these problems or the real divisions in Russian society.

Culture can, and did, feed the war. Culture is not above war; it is a battlefield. In Russian culture, people from all sides of the political spectrum have waged an age-old struggle against violent, repressive autocracy, its chintzy glamorous use of spectacles, its ridiculous level of incompetence, its disregard for human life, and its empty patriotic phrases. I do not think that Chekhov, or Alexander Herzen, or even Shostakovich—who, with a gun to his head, had to publicly swear an oath of loyalty to Stalinism—need me to prove that they were not instruments of the Russian state, which has indeed been almost invariably evil throughout the whole of Russian/Soviet history. Quite the contrary: they are all allies in the struggle against this new incarnation of autocracy, a struggle that must now continue. We all have to reread them, listen to their music, watch humanistic Soviet films again, or for the first time.

As several recent insightful authors have written, the main task ahead is something that could be described as Russia’s decolonization. Russians must finally look at their troubled history of settler colonialism, frontier war, and cultural imperialism, both at home and abroad, to be able to pull out Russian fascism by its roots. They must dissolve the autocracy and admit that this autocratic, elitist Russia itself was always a colonial entity, intent upon enserfing its own population, just as it was displacing, enslaving, and erasing others.

And yes, it is Russia which is bombing Ukraine. And we Russians have to look for another Russia now—maybe in some of its great culture, stripped of its imperial arrogance towards anything with a local accent. Maybe in parts of our political past. Maybe it is in Ukraine now. Or maybe it does not exist yet.