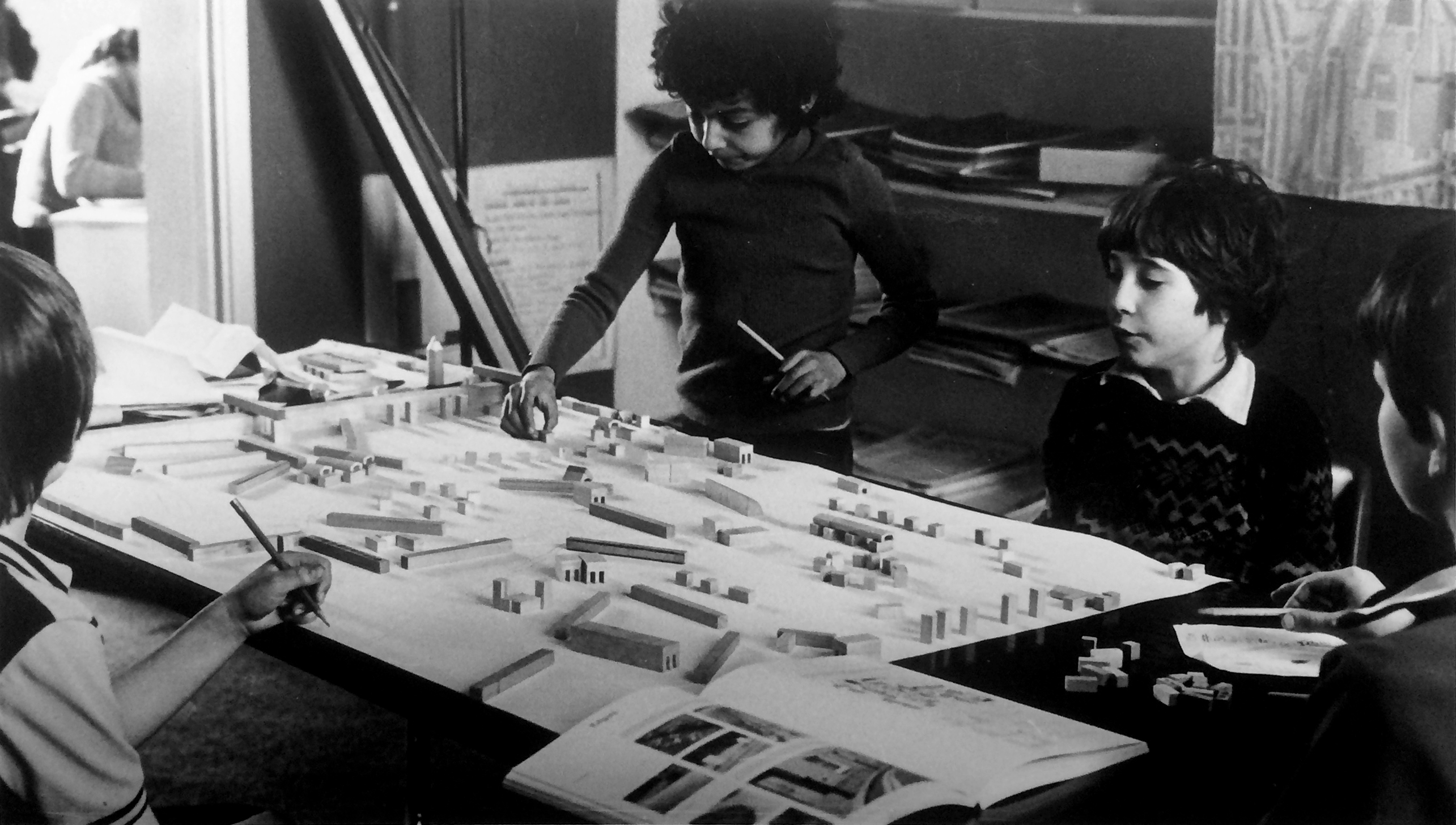

Image via the Indian Express.

There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.

—Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History”

Why are we witnessing a large number of Indians defend and celebrate the Russian invasion of Ukraine? We are a postcolonial nation-state with a long history of colonial domination that has caused irreparable damage to people at large. Despite this, if people cheer for the Russian invasion, it reflects perhaps the latent imperial ambition of Hindu majoritarianism in India and its desire for an “imagined” Hindu Rashtra. In addition to this, the current obsession with the image of a “strong and decisive leader” further cements these celebrations. It seems that urging for and waging war, and the celebration of it, is at the core of national identity. In the context of Britain, the cultural theorist Paul Gilroy has interpreted such aspirations as “after-effects of imperial domination, and responses to the loss of imperial prestige.” They are key components in what Gilroy terms as the “melancholic cultural formations.” And the present-day war on Ukraine by Russia is a classic example of this.

The War of Cultures

The desire for a monoculture is intricately linked to the dream of a “perfect” nation. There are no wars that are not nefarious. And needless to say, war consumes everything along its way. These are often categorized as collateral damages. Despite the sense of unintentionality that the word “collateral” evokes, a close look at the way the mechanisms of war function makes it evident that these claims are made in order to exonerate the perpetrators of destruction from any liability. In other words, wars need to be understood in terms of their mechanistic nature, for their role in spearheading and accelerating the imperial ambitions of majoritarianism of various kind and degree.

Sometimes, wars are not declared, but transmitted as something omnipresent in our lives. For instance, let us consider a manifested form of undeclared war in our context—the destruction of Babri Masjid (1992). A war cry, which still has cataclysmic reverberations in our present. Why did the destruction of a historical monument become the most pleasurable visual metaphor for a large number of Hindus? The answer may lie in the fact that no nationalism can exist outside of cultural insularism or the obsessive desire for territorialization. However, such a love for territory that even expunges the people, culture, and nature is antithetical to democracy as an ideal.

Culture and civilizational claims are the primary rallying point of any territorial imagination, which is what makes a cultural monument the trigger point for the war on people. When the imagined greatness of a past emerges as already lost, political work transforms itself into a war-machine, trapped in desperate, endless attempts to bury the heterogeneity of past. But the war on the past is not an exorcism of its evil spirit; it is the process of transforming oneself into evil incarnate. This incarnation signposts the everyday war that shapes our present-day cultural and political ethos.

The repeated vandalization of Ambedkar statues—a symbol of Dalit reclamation of the public spaces—across India, for instance, is a local manifestation of such internalization of war. As art historian Kajri Jain has noted, the construction of gigantic statues, both religious and “secular”—such as, for instance, the Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel National Memorial—can be read as a violent reassertion by the majoritarian caste groups of their monopoly over public spaces. In that sense, these gigantic statues and monuments are camouflaged forms of war cries. They are erected monumental pillars of the monoculture, challenging the heterogeneity of both past and present. The militarization of everyday life, particularly when associated with the comfort blanket of imagined monoculture, produces constant wars, vandalizations, and furthers the desire to destroy.

The War of Art

German philosopher Walter Benjamin, a direct victim of World War II and the Nazi war machine, in his now canonical essay “Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1935), analyzes the manifesto of the Italian Futurists of 1909, which was one of the most unabashed celebrations of war in the history of Western modern art. Benjamin, in his characteristic style, not only criticized the content of the manifesto as a proto-fascist document, but also was attentive to the language force of the text. A text which thrives on a sense of urgency, a desire for a definitive disruption, a call for catastrophe, as if that is the only way “progress” can progress. Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the author of the manifesto, wrote: “For twenty-seven years we Futurists have rebelled against the branding of war as anti-aesthetic … Accordingly we state … War is beautiful because it establishes man’s dominion over the subjugated machinery by means of gas masks, terrifying megaphones, flame throwers, and small tanks. War is beautiful because it initiates the dreamt-of metallization of the human body. War is beautiful because it enriches a flowering meadow with the fiery orchids of machine guns.”

In his critique of the manifesto, Benjamin noted that such celebration of war by the Futurists is not only indicative of a proto-fascist aesthetical regime, but also reveals its inner logic which celebrates one’s own destruction as the ultimate aesthetical experience—the sublime of the highest order. Benjamin noted, “Humanity that, according to Homer, was once an object of spectacle for the Olympian gods, now is one for itself. Its self-alienation has reached such a degree that it is capable of experiencing its own destruction as an aesthetic enjoyment of the highest order.”

War and Culture

War and the destruction of repositories of culture are intricately connected. War is much more than the mere desire to conquer and occupy. This desire is often fueled by a repulsion towards difference. This is the primary reason that the planned destruction of traces of cultural difference became integral to the war machine globally. We have evidences across geographical areas and historical time periods of such acts of cultural cleansing. We can create an endless list of such destruction from the annals of history—be it the library of Alexandria, the Imperial library of Luoyang, or the Nalanda University, the destruction and conversion of Buddhist monuments in ancient and medieval India, and the Bamiyan Buddhas, to name a few. One of the most telling examples from recent history is the burning of the Jaffna Public Library in 1981 by the Sinhalese militia, which resulted in the destruction of over ninety-seven thousand volumes of books along with numerous culturally valuable and irreplaceable manuscripts. By burning the library, the majoritarian regime aimed to erase the cultural past of the Tamil community, and thereby attempted to push them out of the ambit of history.

The colonization by various European empires also illustrates the fact that such acts involve looting and destruction of cultural properties. The British looting and burning down of the Royal Library of Burma in the late nineteenth century is a case in point. Ironically, some of the artifacts looted by the British army are still displayed as part of the Victoria and Albert Museum collection. The world wars also displayed similar tendencies of willful destruction of repositories of culture. For instance, Poland—a neighboring nation of Ukraine—faced an unconceivable loss of artifacts of its history and culture. The Zaluski library in Warsaw was repeatedly looted and vandalized, first by the Russian occupying forces towards the end of the eighteenth century, and later by Nazi German troops in 1944.

The American invasion of Iraq in 1991 may be the most relevant, recent instance of how war produces devastating and far-reaching impacts on cultural monuments, repositories, objects, and archaeological sites. Legal scholar Marion Forsyth, in her essay “Casualties of War: The Destruction of Iraq’s Cultural Heritage as a Result of U.S. Action During and After the 1991 Gulf War” (2004), noted that prior to 1991, Iraq had one of the most successful cultural property protection schemes in the Middle East. Iraqi national law has considered all immovable and movable antiquities to be owned by the state. The trade in antiquities has been illegal, and it has also been illegal to “break, mutilate, destroy or damage antiquities whether movable or immovable. But once the war destabilized the region, these invaluable artefacts were looted by organized gangs and smuggled into the antique market of Europe and America.”

While assessing the impact of the American invasion on “the cradle of civilization” on behalf of UNESCO, Sue Williams, in her interview with eminent archaeologist John Russell, notes that

The archeological site of Ur of the Chaldees, reputed birthplace of Abraham, was bombed and strafed by Allied aircraft, with over 400 cannon holes reported in the temple tower and at least 4 bomb craters in the site. The unexcavated major site of Tell el-Lahm was trenched and bulldozed by American forces.

A cursory look at the various UNESCO reports on war crimes committed against cultural artifacts and sites reveals the extent of destruction and how war works as an enabler of the illegal global trafficking of artifacts into the international antiques trade. One may go so far as to say that destruction is the business of capitalism and war is its intimate companion, and every destruction opens up multiple market opportunities for capitalists and political opportunities for the capitalist class.

What Remains?

Against these backdrops it may be worthwhile to think about present-day calls to decolonize museums and institutions, particularly in the contexts of erstwhile colonizing/imperial nations. These calls for decolonizing institutions go beyond token gestures of repatriation and restitution to more self-reflexive and critical examination of the culpability of cultural institutions in the imperialist-nationalist-war complex.

So what would a decolonial initiative in India look like? Would we, when the majoritarian Hinduism is clearly on a state-supported warpath towards homogeneity and monoculture, be remotely able to think along the lines of heterogeneity and restoring the ethos of pluralization?

This essay was orignally published in the Indian Express, May 2, 2022 →. Republished with permission.