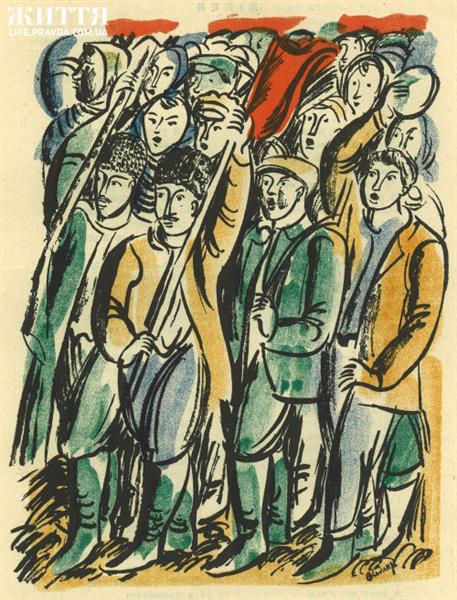

Vasyl Sedlyar, Illustration of Taras Shevchenko, Kobzar (1933)

Anastrophe—“turn up” (Greek ana “up or back” + strephein “to turn”), the antonym of the word “catastrophe” (Greek “turn down”)—is defined in Mikhail Epstein’s Projective Dictionary of the Humanities as “a turn to happiness, social euphoria.”1 “Anastrophe,” Epstein clarifies,

is not just luck. This event is sudden, unstoppable and large-scale, affecting the fate of many people like an earthquake or a volcanic eruption, but with the opposite sign: happiness shaking, happiness eruption. It brings renewal and mass spiritual uplift, although its consequences in authoritarian states can be negative and strengthen totalitarian tendencies (“mass enthusiasm”).2

In nature, Epstein notes, there are no sudden causes of universal happiness, there are no tsunamis with a “+” sign, but anastrophe is not rare in historical life. As examples of anastrophe, he cites Victory Day on May 9, 1945, Gagarin’s flight into space on April 12, 1961, the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, etc.

Recently, a striking example of an anastrophe in the post-Soviet region was Russia’s annexation of Crimea in spring of 2014 (the so-called “Crimea of Ours”), which caused the euphoria of a “happiness eruption” that illuminated the bleak everyday life of the Russian population in an era that Franco “Bifo” Berardi calls “the era of impotence and depression.”

A new powerful anastrophe, provoked by the Putin regime, was the catastrophe of February 24, 2022—the beginning of Putin’s aggression against Ukraine—which, unlike the “Our Crimea” anastrophe, became not only a Russian but a global anastrophe that caused a worldwide wave of mass enthusiasm, a general mobilization in the field of morals. Finally, after many years of ethical instability, or, in Artemy Magun’s terms, ethical negativity,3 the time has come for ethical stability and positivity: good and evil are separated, all significant political subjects are ethically marked as heroes or as villains, and, most importantly, the self-identification of individuals as ethical subjects has acquired a total and universal character. Every politically determined subject, regardless of its political and party orientation, can finally feel him- or herself empowered to fulfill the impossible ethical maxim of Kant’s categorical imperative: act in such a way that the maxim of your will can be accepted as a universal law.

The difference with the ethical anastrophe that occurred after February 24, 2022 is that its main collective affect is not the affect of happiness and joy, but the affect of hatred, or “hatreds,” in the words of the American feminist Zillah Eisenstein,[footnote Zillah Eisenstein, Hatreds: Racialized and Sexualized Conflicts in the 21st Century (Routledge, 1996).] which are found as metastases everywhere, becoming a powerful resource for mass political mobilizations, including racist, nationalist, and sexist ones. Moreover, in the regime of sensuality that is established in the situation of the war in Ukraine, the hatred liberated and legitimized by the war turns out to be a truly general and universal affect that knows no class differences and unites people regardless of their social status, cultural differences, and education. (Recently, I read a Facebook post by a Russian-speaking priest from Italy, who reports that the most common sin that all immigrants from Ukraine and Russia confess to him today is hatred. And this priest admits that he struggles to find words to somehow support people who confess the sin of hatred.)

Hence the key question of modern ethics in the state of emergency today: should we recognize such an affect as the affect of hatred, generated by war, as evil incompatible with good and the ethical sphere, or, on the contrary, should it be included within the field of ethics and the conditions for its ethical application determined?

Or the same question in the form of an antinomy:

1) Where there is malice and hatred, even if it is “just” hatred, there is not and cannot be virtue and morality.

2) Hatred today is the modern form of morality and doing good today means following the call of one’s hatred.

What solutions to this antinomy are offered by contemporary philosophers who theorize ethical problems?

The solution that seems preferable from the point of view of the humanistic tradition is to restrain affects, passions, and inclinations that are detrimental to ethics and pass over to the “bright side” of reason, logos, and civilization, or, in other words, to bet on the human versus the dehumanized. Today in Ukraine, which is on the “bright side,” this humanistic point is represented, in particular, by the popular Ukrainian philosopher and blogger Andrey Baumeister (his YouTube channel has about two hundred thousand subscribers). Claiming the mantle of Aristotle and neo-Aristotelianism, he offers an ethical philosophy focused on the transition from “just living” (zoe) to “good living” (eu zen), which he defines as the “ethics of goodness.” Virtue ethics involves the rejection of selfishness, mercantilism, and the principle of pleasure. By following it, a person acquires, first, happiness, understood as a civilized way of life, culminating in intellectual life (realized in the pursuit of knowledge) and the formation of “bios philosophicus” and, second, a higher social status (“everyone can become part of one or another elite”).4

For a modern person as a product of mass culture, the implementation of this position will require, according to Baumeister, certain restrictions, even censorship, necessary to comply with the civilizational norm. No one can be exempted from ethical criticism. In Ukrainian society and culture, even such a cult figure as, for example, Taras Shevchenko cannot escape criticism: his poetry, according to Baumeister, contains too much uncivilized hatred and malice. In order for Shevchenko’s Kobzar to be consistent with virtue ethics, it would be necessary, Baumeister argues, to reduce it tenfold and to exclude its most xenophobic and misogynist parts from the school curriculum.5 On the other hand, Russian culture does not deserve total abolition, the image of Russian culture as totally colonial and repressive is a myth, and there are many different stages of interaction in the history of Ukrainian and Russian culture.6

Will the Ukrainian cultural mainstream agree to such measures of ethical self-criticism and self-censorship? Is modern Ukrainian society ready for this “ethics of goodness” in a situation of war with Russia?

Instead of neutralizing and isolating affects, perhaps we should turn to a more modern philosophical methodology for interpreting them, taking into account the situation of the so-called affective turn in the social and human sciences and positively assessing affects as an important sociopolitical factor. A crucial guide in Russian-speaking philosophy is Artemy Magun, who in his recent book From Trigger to Trickster: Negativity in Ethics develops an original version of the “ethics of negativity” or “ethics of evil,” in which the ethical subject is constituted precisely through affect (the temptation of atrocity, “sinfulness”), prompting him to constant ethical reflection and to question himself.7

Contemporary ethics, Magun argues, is a dynamic structure that requires thinking dialectically. Good and evil do not simply oppose each other, but represent a unity of opposites (“are in an intimate relationship”), and, therefore, the new task for ethics is not a matter of good, duty, and virtue, but of one’s own evil.8 An ethics that strives to remain only on one side—the “bright side” (like Baumeister’s “ethics of goodness”)—is not only a utopian but also not an ethical project. In order to take a truly ethical position, to become a moral person (Homo moralis), the subject, according to Magun’s theory, must accept the ineradicability of affect (and malicious intent) in his or her own personality and work with it.

To do this, Magun offers a set of specific practical behavioral recommendations (“communicative attitudes in relation to another”), which should help a subject who is in a state of passion to survive the affect and at the same time not fall (not “plunge,” in the words of Magun) into depression and melancholy, dooming the subject to passivity or hysteria, capable only of pseudo-action and resistance to authority.9

Is it possible to apply the communicative attitudes and methodology of the ethics of negativity to the situation of the war in Ukraine, and can we resolve ethical antinomies with its help? Does it give an answer to the question about the relation of the affect of hatred to ethics, i.e., the question of its ethical relevance? Indeed, among the basic affects that Magun cites as allowing the subject to realize an ethical communicative attitude towards another (anger, anxiety, sadness, compassion), there is no affect of hatred …

The philosophy of feminism is another resource offering a rich engagement with the phenomenon of affect. According to feminist philosopher Judith Butler, an ethics that relies on identity and positivity, like Baumeister’s “ethics of goodness,” cannot in principle qualify as ethical in contemporary culture. Butler calls this stance “moral sadism,” as it requires us to constantly manifest and maintain self-identity and demand that others do the same. As an example of moral sadism, she cites the case of Georg Bendemann’s suicide from Kafka’s story “The Judgment,” in which the father condemns his son to death, sadistically using the mechanism of George’s self-identification as a loving and beloved son, formed by him.10

On the other hand, the problem with theories of ethics based on the concept of negativity, according to Butler, is that they often adhere to a punitive version of the origin of ethics, dating back to Nietzsche, where morality is understood as arising from fear, a reaction to punishment.11 Ethics in this case is born of resentment, a “slave morality” cultivating a sense of guilt as an effect of internalized aggression. In such a theory of ethics, from Butler’s point of view, there is no place for conscience, which she defines as the subject’s ability to independently give an account of oneself.

In order to include the concept of conscience in ethics, Butler argues, an alternative ethics to one based on punishment/repression is needed, such as Adriana Cavarero’s altruistic relationship ethics, in which the main ethical question is “Who are you?,” implying that there is an other who is not known by me.12 In this case, according to Butler, we ask the other questions without expecting an answer that would satisfy us, allowing the question to remain open and, thus, allowing the other to live. In this case, according to Butler, the relation of the subject to other is not determined by resentment, the feelings of anger and hatred.

Is such an altruistic ethics of relations possible in a situation of war? May I ask the question “Who are you?” to my national enemy, who I know for sure is my enemy?

As a feminist friend from the former Yugoslavia wrote to me recently, “For all of us who find or found solace and political wisdom in Butler’s theory of nonviolence, these are trying times. I struggle. I believe in nonviolence as Butler theorizes it. But it’s hard to stand by it when Ukrainians are bleeding. Not because the concepts do not hold when confronted with Putin, but because of how emotions change, and how easy it becomes for us to embrace violence.”

Mikhail Epstein, Проективный словарь гуманитарных наук (Projective Dictionary of the Humanities) (NLO, 2017).

Epstein, Проективный словарь гуманитарных наук (Projective Dictionary of the Humanities).

Artemy Magun, От триггера к трикстеру: Негативность в этике (From Trigger to Trickster: Negativity in Ethics) (Gaidar Institute, 2022.)

Andrey Baumeister, “Чему мы сегодня можем научиться у Аристотеля?” (What Can We Learn from Aristotle Today?), February 6, 2021, YouTube video →.

Andrey Baumeister, “Баумейстер Андрей. Есть ли будущее у наций? Лекция и ответы на вопросы” (Do Nations Have a Future? Lecture and Q&A), January 21, 2022, YouTube video →.

Andrey Baumeister, “Не хотелось бы становиться анти-Россией” (We Wouldn’t Want to Become an Anti-Russia) July 25, 2022, YouTube video →.

Magun, От триггера к трикстеру (From Trigger to Trickster), 93–94.

Magun, От триггера к трикстеру (From Trigger to Trickster), 174.

Magun, От триггера к трикстеру (From Trigger to Trickster), 329–30.

Judith Butler, Giving an Account of Oneself (Fordham University Press, 2005), 46–49.

Butler, Giving an Account of Oneself, 10–11.

Butler, Giving an Account of Oneself, 31.