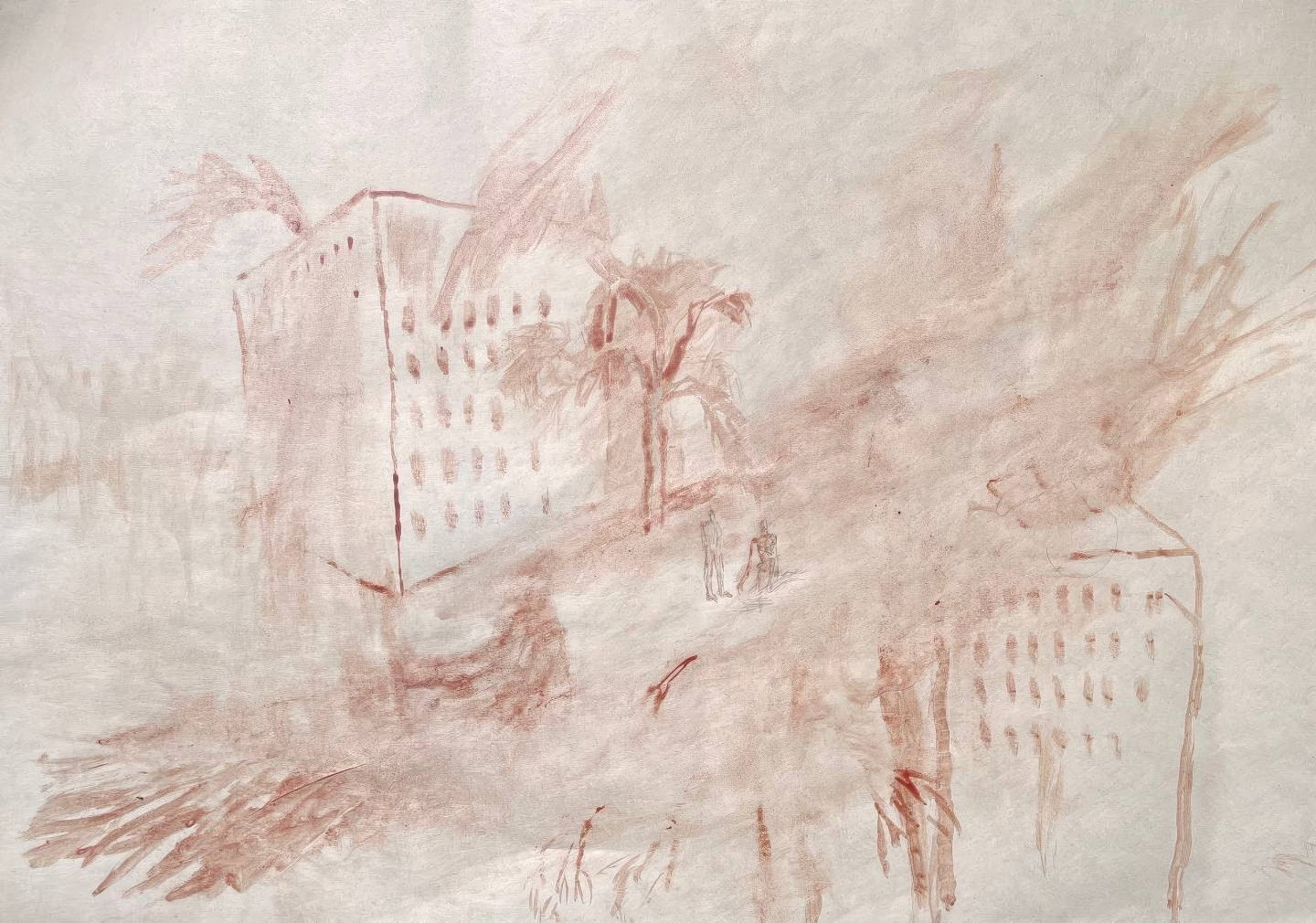

Kyiv 2023. Photo by Oleksiy Radynski.

Around a year ago I published a short essay titled “The Case Against the Russian Federation.” Written during the very first days of the Russian invasion, this text was conceived as a brief outline of decolonial arguments with regard to Russia that seemed to be pretty basic—almost a bunch of truisms. To my surprise, after this text circulated relatively widely, I started to receive feedback saying that it had worked as a kind of eye-opener for many readers, forcing them to think for the first time of the Russian Federation as a colonial modern state. On several occasions, I was even told that the idea of Ukraine being Russia’s colony was something absolutely new for a lot of the audience outside Eastern Europe.

I have to admit that I’ve been slightly confused by this kind of feedback. It was clear that this wave of reaction towards my text was, to put it mildly, a sign of a long-term, deep-rooted misunderstanding of the Russian Federation on the part of those outside its colonial orbit. It is actually very disturbing that so much effort still has to be put forth to explain that the Russian Federation is a settler-colonial, racist regime that still exploits and exterminates its non-white populations en masse—most recently, by sending disproportionate numbers of its non-Slavic subjects to die in the Ukraine invasion.

If the settler-colonial background of the Russian Federation is not crystal clear by now—at least in intellectual and academic circles—then some uneasy questions arise. For instance: What’s the use of the gigantic apparatus of academic study and analysis of Russia in the West, if it’s been turning a blind eye to Russia’s genocidal settler colonialism for such a long time? In fact, the awakening of this academic apparatus from its enchanted dream about Russia as some kind of distant, mysterious, Eurasian “Other” only happened when Putin started another in his series of brutal wars—this time, so close to the borders of the EU that it finally become impossible to ignore in the First World.

What if this machine of “Russian studies” in the West is actually complicit with the ideological trajectory of the Russian Federation, at least by way of endorsing and promoting the extremely problematic myth of “great Russian culture” as something fundamentally separate from not-so-great Russian politics? Why is it still widely accepted to refer to the construct “great Russian culture” at all (a construct that’s in fact unrelated to the actual merits of the Russian cultural canon, formed in the imperial center), while any talk of “great German culture,” “great British culture,” or “great American culture” inevitably—and rightly—sets off alarm bells, signaling obviously nationalist, imperialist, and supremacist overtones? The answer is: some imperial powers have at least started to engage in the process of reckoning with their brutal pasts, while others—like Russia—still remain in blind denial about their settler-colonial origins. And Western academia had been hugely instrumental in maintaining this blind denial.

Only a year ago, decolonial discourse on the Russian Federation was fairly marginal—largely ignored outside former Russian colonies like Ukraine, or current Russian colonies like Belarus. While important works on the topic emerged from time to time in Western academia, they were mostly ignored by the intellectual mainstream. But now, this discourse is finally gaining global attention. Seminars and conferences on the matter are organized at all levels, from small leftist online reading groups to film programs and art exhibitions, to panels organized by the European Parliament. But anti-colonial thinking and practice with regard to the Russian Federation currently faces a major obstacle: the global decolonial discourse itself still remains largely Western-centric. This discourse is—for a good reason, of course—so focused on the egregious crimes of Western European racialized maritime colonialism that it remains partially blind to other forms of colonial domination that do not fit the established patterns.

For instance, when the metropole and the colony aren’t separated by an ocean—like Moscow and Siberia, for instance—the colonial character of their relationship is far less obvious. Russian resource colonialism is a highly complex and multifaceted system of domination that suppresses both its white and non-white subjects. Facing this complexity, decolonial discourse needs to become more nuanced and sensitive to forms of colonial oppression that do not follow a well-known script.

Over the past year, as a result of Russia’s spectacular military failures in Ukraine and its increasingly disastrous domestic policies, the prospect of a coming collapse of the Russian Federation has become widely debated, not just in Russia itself (where this has been a matter of concern since the early 1990s), but also globally. But what’s misleading about this discussion is that it is carried out in the future tense. The decomposition of a failed federation should not be seen as some kind of projected result of a Russian military defeat or economic chaos. This collapse is not a matter of some distant future—it is happening now before our naked eyes.

What we’re witnessing right now is the third (and potentially final) act of the dissolution of the Russian Empire. The first act started in 1917 with the February revolution, and culminated in Lenin’s decision to accept the independence of some of Russia’s colonies (this list, initially, included Ukraine). The second act unfolded in 1991, with the crumbling of the USSR, which, since Stalin’s time, was nothing but a slightly modernized Russian Empire. The third act started immediately after the Soviet collapse, when the colonized nations that didn’t have their own “socialist republics” within the USSR intensified their anti-colonial efforts against the newly established Russian Federation.

In fact, since its emergence as a sovereign state in 1991, the Russian Federation had been mired in brutal internal strife, a series of civil and ethnic conflicts that have taken various forms over time (from open civil war in the streets of Moscow in October 1993, to the brutal suppression of Ichkeria during the “Chechen wars,” to the abolition of self-governance in the Federation’s “republics” since the early 2000s). But to prevent this internal strife from consuming the colonized territories still subjugated by the Russian Federation, the Russian government has continuously exported this suppressed violence beyond its own borders: to the territories of its former colonies, first Georgia and then Ukraine. The protracted collapse of the Russian Federation is actually the reality we’ve been living in for decades now, and the invasion of Ukraine is just one of the symptoms of this ongoing cataclysm. In a botched Oedipal logic, the Russian Federation invaded Ukraine because it assumed that this was the last chance to preempt its own demise. Instead, it’s been caught in the quagmire of a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Of course, the prospect of the ultimate demise of the Russian Federation—when seen as a distant possibility and not the ongoing process that it actually is—seems frightening and undesirable to many outside the region. The same was true with the collapse of the Soviet Union, a much more fearsome power structure whose disintegration into fifteen sovereign states was in fact feared and unwanted by its Cold War adversaries (including the White House, which only abandoned its attempts to keep the Soviet Union together—provided that it renounce communist ideology—in late 1991, when the Soviet collapse became obviously unavoidable). Just as with the Soviet disintegration, the demise of the Russian Federation will be ensured by its own internal dynamics and not by some global political masterminds, who seem to be very much unconvinced about the emergence of new decolonized nations in northeast Eurasia.

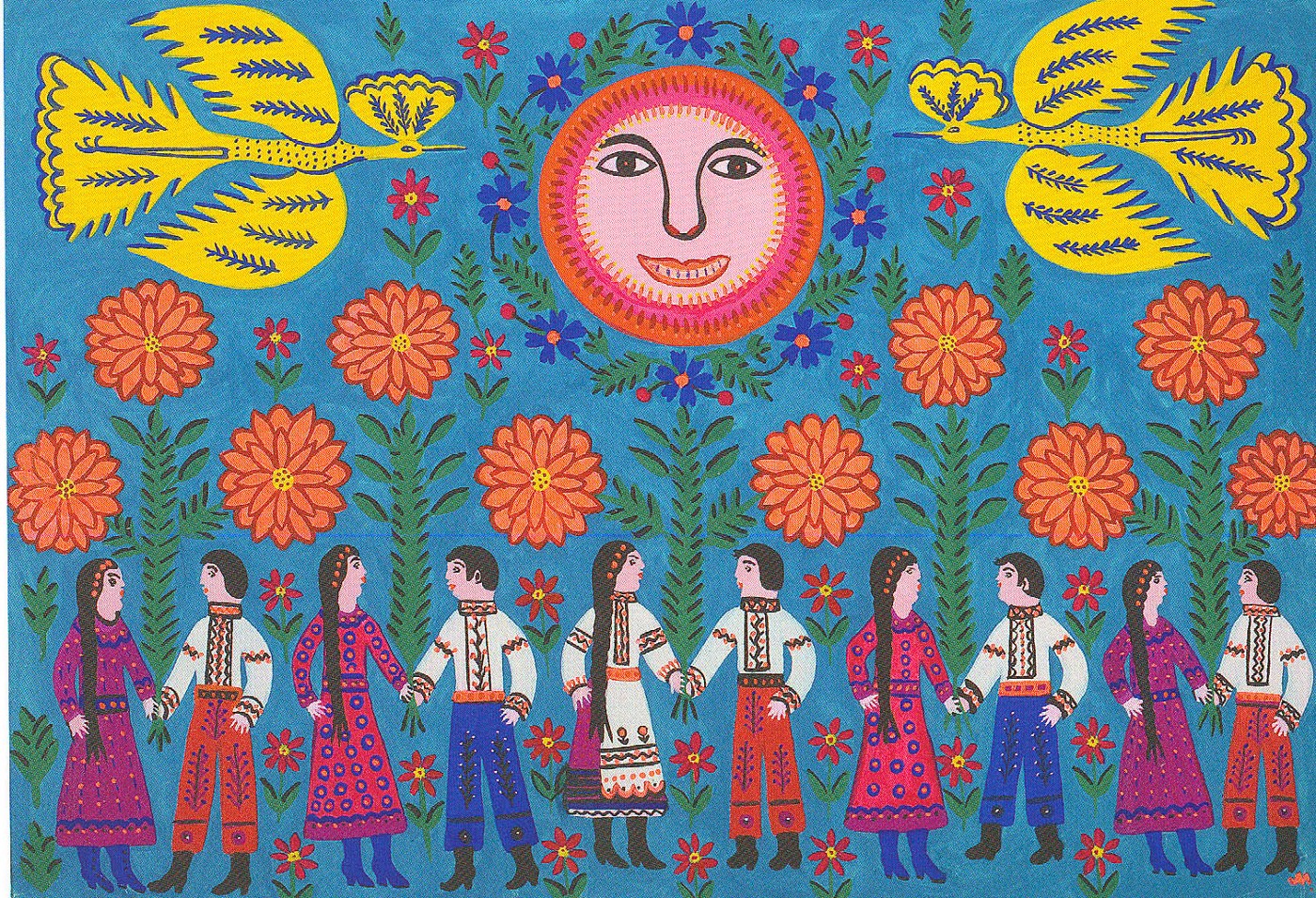

Last year, I was giving a talk to an audience in Germany on Russian colonial tactics towards the non-white peoples who are currently oppressed subjects of the Russian Federation. After my talk, some members of the audience asked confused questions: What kind of non-white peoples in the Russian Federation are you talking about? Are you not aware that Kazakhstan and other “non-Russian” Central Asian republics have been independent from Russia for a long time? Very soon, the West will have to educate itself about dozens and dozens of peoples inhabiting the presumably “white” Russian Federation. To name just a few: the Nenets, the Tatars, the Chuvash, the Bashkirs, the Udmurts, the Kalmyks, the Chechens, the Dagestani, the Buryats, the Sakha (the full list would probably be longer than the word count of this publication allows).

The Russian Federation is an extractivist empire that colonizes and exploits fossil-fuel-rich lands just as it colonizes and exploits its people. In fact, these lands ended up in Russian possession as a result of the brutal extermination of local populations, which was carried out with such ruthlessness that even the basic facts about these massacres have been erased from public knowledge. The most telling—and unspoken—instance is the erasure of any mention of the Indigenous peoples inhabiting the mouth of the Neva River prior to the construction of the imperial capital of St. Petersburg.

The Russian oil and gas that’s been so eagerly consumed by the West actually originate from the unceded lands of Siberia and the Arctic, where Indigenous peoples are subjected to ongoing assimilation and extermination. In that sense, Ukraine has plenty in common with, for instance, the Russian-occupied peninsula of Yamal, which feeds the Russian fossil fuel industry with natural gas. Both Yamal and Ukraine are links in the fossil fuel supply chain that stretches from Russia to the West (the Nord Stream pipeline being just the most notorious part of this supply chain). With global fossil fuel consumption in decline, the Russian Federation is emerging as one of the biggest losers of the ongoing climate crisis, which it very much helped to bring about. The invasion of Ukraine is a desperate attempt to survive this ultimate failure of Russia as the declining raw material appendage of the West.

Russia is an empire that colonizes adjacent lands for resources, but it’s also a resource colony of the West. The inconvenient truth about this invasion is that it was initially largely funded by Western, most notably German, public money in the form of exorbitant fossil fuel revenues paid to the Russian Federation. But on a deeper level, the Putinist regime is in fact very much a product of Western politics. It is an outcome of one of the most profound and uncompromising Westernization processes in Russian history, taking place in the 1990s.

Sadly, this Westernization took the form of perhaps the most extreme fundamentalist market reform in history. In post-Soviet Russia and other post-Soviet republics, conditions in the 1990s seemed ripe to install some of the most free-market regimes ever seen on earth. This was a mode of capitalism completely devoid of any checks and balances (which actually make Western capitalist models at least seemingly viable). Here, market fundamentalists saw a chance to impose a purer capitalism than would ever be possible in the US or elsewhere. The workers’ rights movement was utterly defeated and disoriented, unions were nonexistent, and the ideology of egotism and greed found fertile ground in the population after decades of pseudo-socialist collectivism. The results of this “pure market” model are clearly displayed in the case of the Russian Federation: it swiftly led to monopolistic capitalism coupled with right-wing authoritarianism, then to outright militarized fascism. But the starting point of this trajectory lies in the strategy that the winning side of the Cold War chose to impose on the losers.

The Western policy of assistance to Ukraine is often framed as a matter of solidarity, or even charity. But in fact, in its support of Ukraine, the West is merely trying to fix its own recent catastrophic blunders during the post-Soviet era. It might of course be confusing for many that the white settler empire that is the United States has found itself supporting a decolonial struggle against another white settler empire, the Russian Federation. But in fact, in the case of Russia, the West is not opposing some kind of exotic orientalist Other. It is opposing its own ugly double, which simply took Western racist, extractivist colonialism to its extreme. The demise of the Russian Federation will prefigure the demise of other extractivist empires, and the liberation of their subalterns.