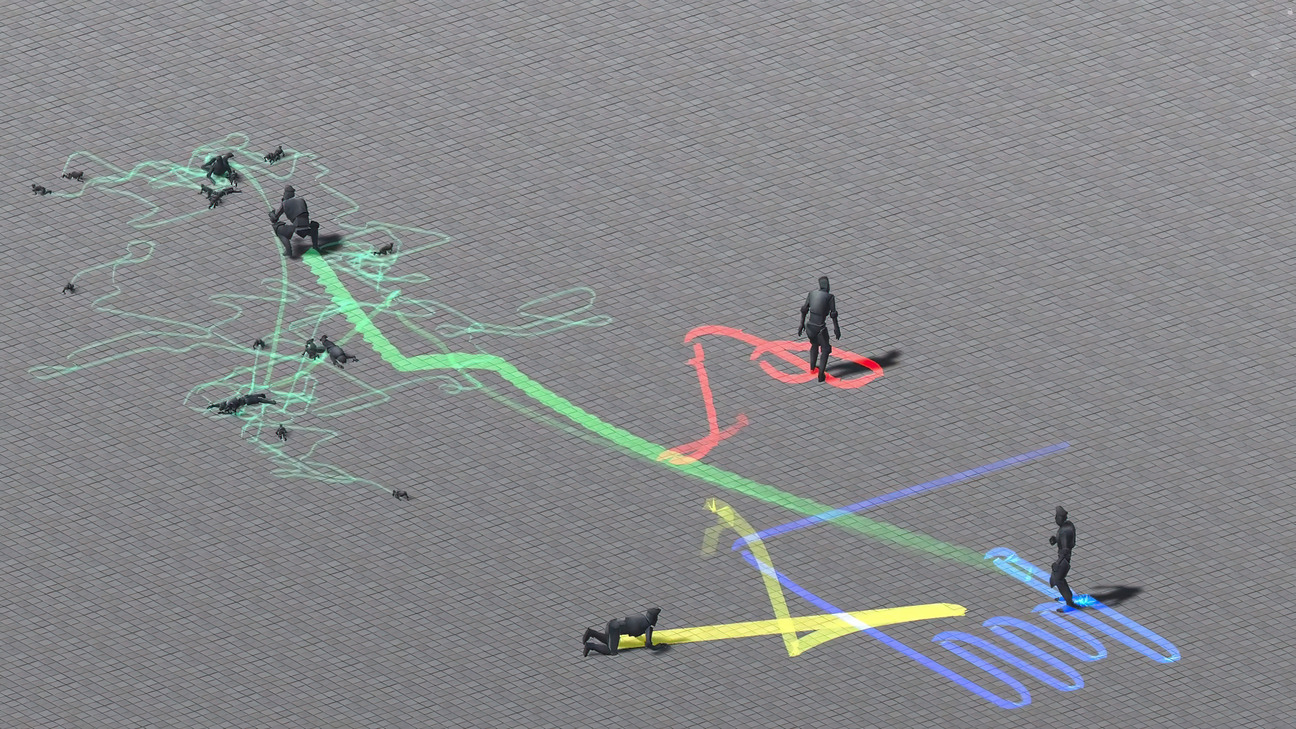

Still from Agnieszka Polska, The Thousand-Year Plan (2021), a two-channel video installation.

Last year we presented several works by Agnieszka Polska at e-flux Screening Room. The screening was followed by an in-depth conversation between the artist and Lukas Brasiskis. The transcript of this conversation was edited for the present publication.

e-flux: You mentioned that it is hard for you to talk about films you made many years ago since you were in a different creative mindset back then. However, I find it fascinating to think about your older and newer works together. There is something consistently distinct in your approach to genre, form, and the questions you explore, even from your earliest films. Could you speak about how you started working with animation and computer-generated images?

Agnieszka Polska: Animation was actually my first medium. I started with traditional animation techniques, such as glass table animation, where you divide frames into layers of content moving at different speeds: what is closest to the viewer moves fastest, what is farthest seems not to move at all. Then I moved to digital animation and later became interested in immersing viewers in my films. I began experimenting with installations and unusual film presentation methods, such as full-dome technology, used in planetariums. Parallel to that, I became interested in different storytelling formats, which led me to writing and directing for cinema and theater.

To be honest, it’s difficult for me to see one shared element across my films. The limit of the moving image lies in the human eye and ear, the only tools we have to receive it. And for the sake of tricking the eye, in any format you need layers of content moving at various speeds. I think that deconstructing an image, an emotion, a story, into layers—layers as a manifestation of different scales—then endlessly stacking them up into a complex structure is what might be my general method.

As you mentioned, I don’t enjoy talking about my old works. Initially, my films were heavily influenced by art history, exploring what it means to be an artist and the responsibilities that come with it. However, gradually I decided to move away from making films solely for art curators and artists. I became ashamed at the thought that a person without interest in art history might not understand my work.

e-flux: Your installations often feel immersive, not just through the scale of the screen and the sound but also through intersubjective spaces that you create, where images establish direct contact with the viewer. How do you balance immersion with narrative and thematic elements in your films?

AP: My approach combines immersion with a degree of dissociation. On one hand, I aim at creating a charming hallucination, fully capturing the attention of the viewer. But this hallucination is broken by moments of alienation that prevent the work from becoming nihilistic. This balance helps maintain an effective dialogue with the audience. In filmmaking, we might want to follow the psychoanalytical concept of the “good enough mother”: a parent caring enough to comfort their child with the illusion of magic, but not enough to prevent the child from discovering the hollow external world. I’d like to think about the necessity of being a “good enough artist”: acknowledging the external world and the disillusionment that comes from it in one’s practice, without giving up the hallucination of beauty. Moving images can convey empathy, but they have to be balanced to seduce the viewer without making them apathetic. That’s at least what I’m trying to achieve. I see films as units of stored emotions that circulate through society in economic fashion.

e-flux: I would like to ask about detachment in your work because it seems like irony and melancholy are employed very specifically at certain points in your films. I was wondering about that as an artistic tool and maybe as a political tool in your work...

AP: Yeah, definitely. Maybe these are elements that join my works together—the irony and humor mixed with melancholy. It is very much connected to the process of dissociation. A joke is always dissociative, while melancholy drags you into the work. The final edit is about finding the right balance between these two elements.

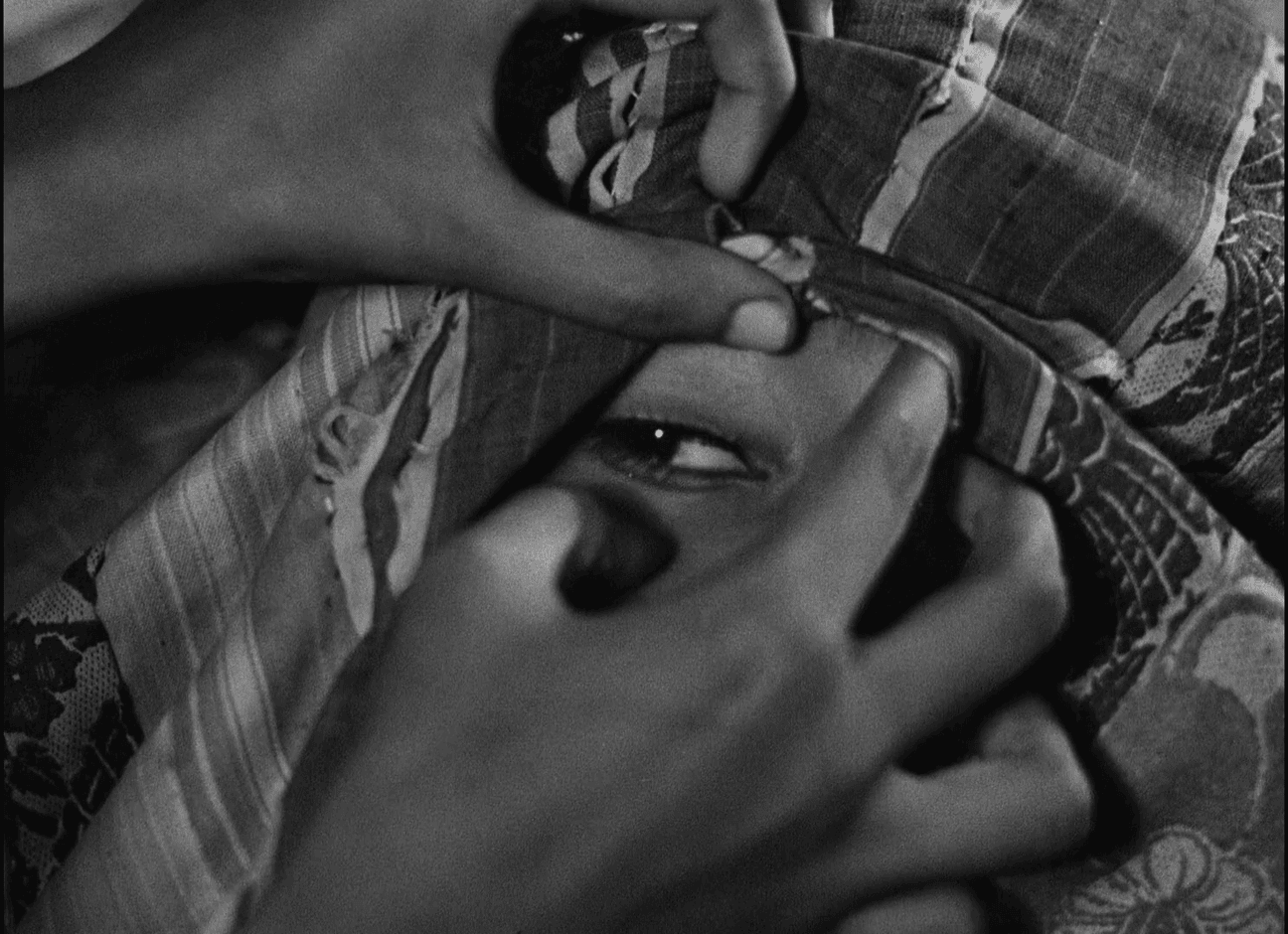

e-flux: It seems that often you invert the cinematic gaze, making it collapse on itself, and, in this way, you make the viewer realize how easily one is manipulated into certain feelings. Could you discuss your approach in terms of the gaze, perhaps also in relation to the techniques of seriality and repetition in your work?

AP: Manipulation is an obvious result of editing, but with new technologies there is a whole new level to it. In my work it is never a manipulation of facts. It is always an affective manipulation, where I impel the viewer to enter certain emotional states. There is poetry, which obviously propels emotions, but there are also direct triggers—like an almost-recognizable sound motif, tunneling movement, gaze into the camera, repetition of choreography and speech—that lock the viewer in a feeling. But I’m not a propaganda creator; my films are nuanced accounts of human experiences in a dynamically changing world, so I introduce moments where this manipulation gets broken and, as you say, the gaze of the viewer is reflected onto them.

For example, in the animation The New Sun, the eponymous character, a child-like star, engages in a highly emotional monologue: “They say if something catastrophic were to happen, all that remained were the words that I spoke to you.” This moment of elation is broken by laughs and swearing from an invisible audience; the charm is broken, the lover is humiliated.

Persuasive technologies are generally not ethical, but I believe it is ethical to use them if they are broken into elements that lead to the viewer’s self-realization. The audience is an intrinsic part of the work—the effect on the audience completes the work.

e-flux: Your works blend documentary and fiction to create a unique reality. Some of your films are based on specific events, but they do not explicitly present them. How do you treat history in your work? Is it less about representing the past and more about appropriating it?

AP: I think my films do represent history, albeit in a special kind of way. For example, The Thousand-Year Plan, a film about the expansion of the electric grid in rural Poland during the 1950s, shows a surprise encounter between communist engineers constructing the power line and nationalistic partisans hiding in the forest. Such a situation didn’t take place to my knowledge, though it is plausible. But these historically accurate characters, backed by extensive research, seem to have a supernatural premonition of the future Information Age. They dream of rivers filled with data and a type of world unity that contradicts their either communist or nationalistic ideas of integration. A thorough study of Eastern European electrification revealed that in fact the whole process had an anarchist quality: it was not as much centrally planned as it was a result of each village self-organizing to get connected to the grid. This factual observation is enclosed in often-fantastical imagery of power literally traveling through the environment.

The curator Natalia Sielewicz, with whom I collaborated on this film, half-jokingly described the style of this work as “magical socialist realism,” and even though I’m not fond of magical realism, I think she made a point. My work often focuses on revolutionary moments for human and non-human figures who are usually omitted from grand histories. On the other hand, the “magic” comes from not respecting restrictions of linear time, space, and scale.

Then, there is a surreal quality to any historical event. In my other work, The Demon’s Brain (2018), I look at the plight of a fictional medieval messenger working for a salt mine who loses his horse and encounters a demon; the poor boy is instructed that the future of humanity lies in his hands. While bird-like demons and disembodied horse heads flying through the mine corridors may seem unreal, I imagine anyone would be much more aghast reading the actual historical correspondence of a Polish mine owner from the fifteenth century. It describes forests turned to deserts, women naked because of the lack of textiles, people escaping villages in fear of “bad air” (the plague), perpetual choirs of rotating Christian monks singing twenty-four seven.

e-flux: In terms of the current media landscape, what do you think about the role of AI tools in the creative process of reflecting on truth through fiction?

AP: The Book of Flowers (2023), my latest moving-image work, was created with the help of AI-powered tools. I used initial footage of stop-motion animations of flowers from the 1950s, which was then replaced by AI-generated imagery. This process made me realize how easily filmmaking modes will change. I wrote an article for e-flux Notes where I imagined a future with radical personalization of film content: customization in characters, plot points, endings.1 The future of filmmaking might shift towards world-building rather than traditional storytelling.

To me, stable diffusion models are just another tool I use in filmmaking and image production. But when it comes to their philosophical aspect and the question of reflecting on truth—the arrival of the first generated image automatically eradicated any possibility of a “true image” existing again, because unquestionable “truthfulness” ceased to exist. Ursula K. Le Guin wrote on how the telephone is not a medium of human communication; similarly, Artificial Intelligence is not a medium of human knowledge.

e-flux: The Thousand-Year Plan to me looks more narrative and character-centric than your previous works. Do you feel your style of and interests in moving-image making are changing? Have you ever thought about working on a feature narrative film that could be shown in cinemas and presented in film festivals?

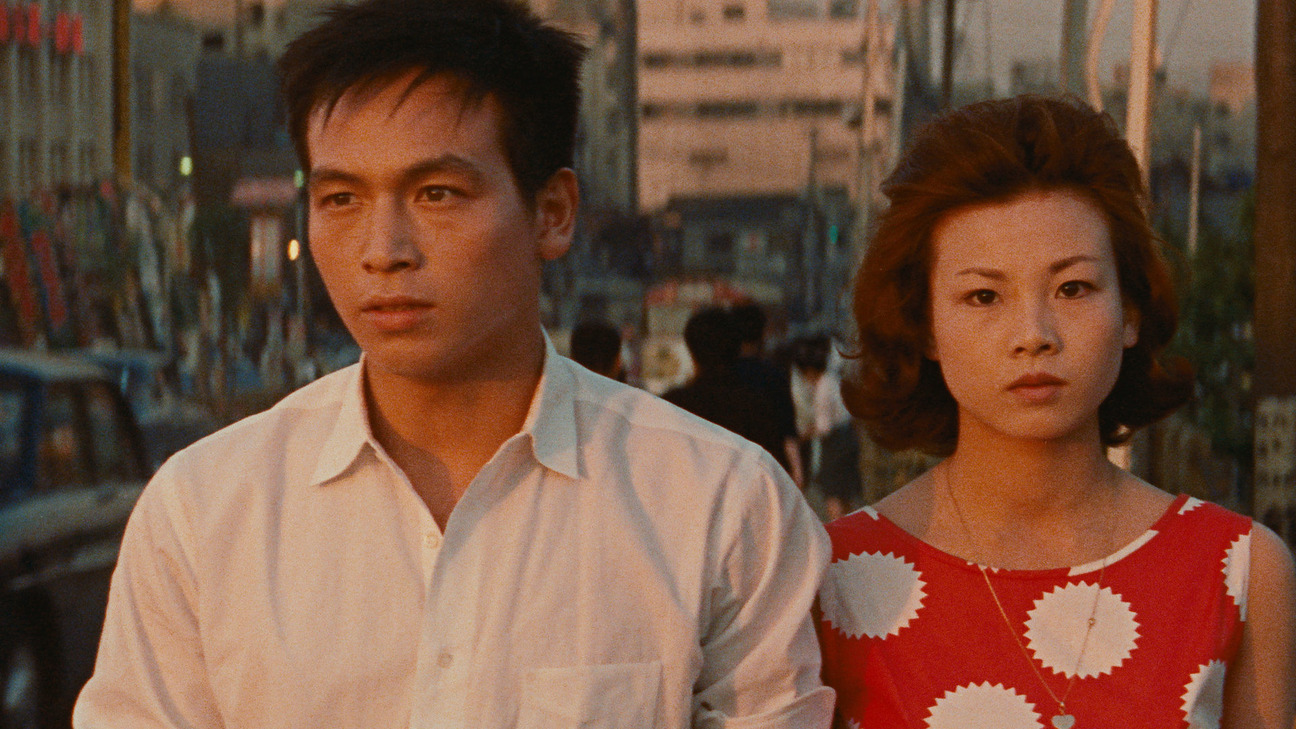

AP: My interests in narrative have been changing already for a while. I debuted a cinematic feature film Hurrah, We Are Still Alive! in 2020, and I have written a second feature-length script. Last year I wrote and directed a theater play. I would like to direct more in the cinema and theater, while continuing to work in the field of visual art.

But honestly, sometimes visual art feels more like a job than a language, and it’s a disheartening feeling. I have a simple, strong need to tell longer stories, to study psychological dimensions of a character, to be granted a longer time to talk to the viewer. A lengthier screening time requires a completely different narrative, and in the last years I indulged myself by constructing long stories. My friend Janek Simon once laughed that we artists are allowed to show a two-hour-long take of a leaf moving in the wind. But the truth is that it’s offensive to let anyone watch a two-hour-long take of a leaf.

e-flux: Has traditional narrative cinema influenced your artistic ideas? Are you personally interested in cinema? If so, who would be your favorite filmmakers?

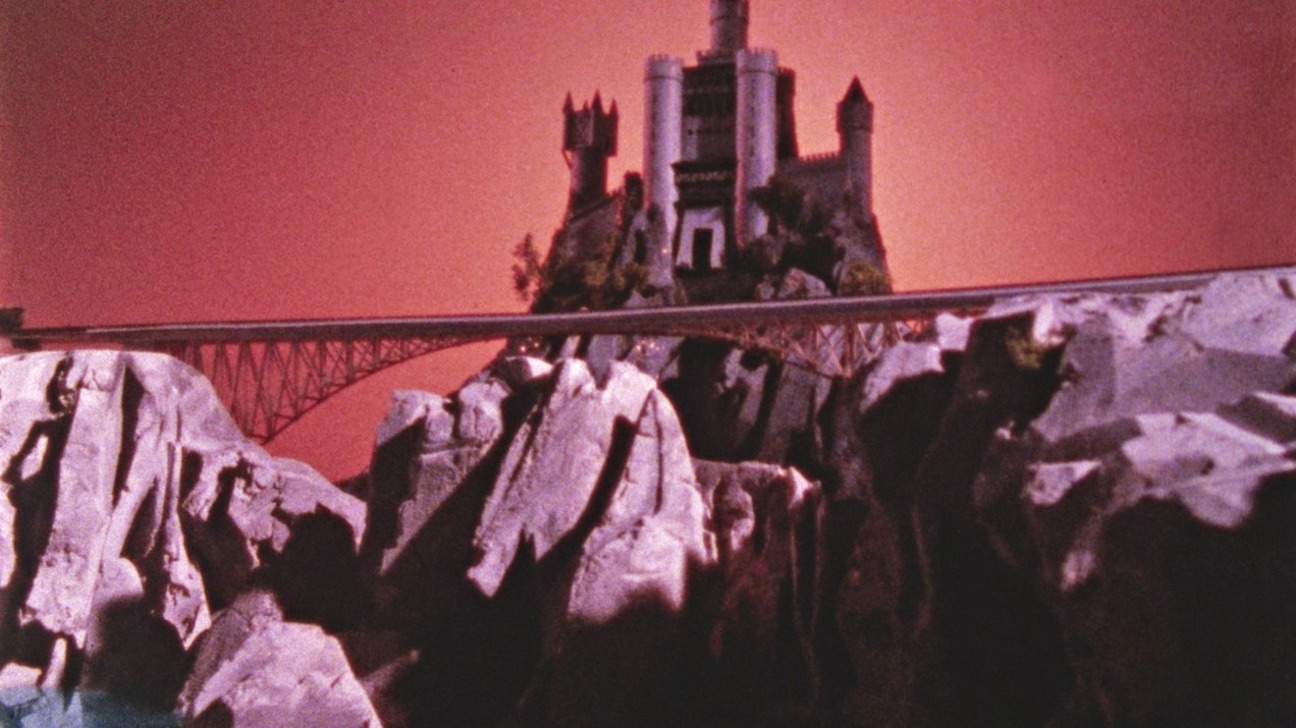

AP: I watch a lot of cinema. I especially value the artistic language of Andrzej Żuławski, Satoshi Kon, David Lynch, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Rainer W. Fassbinder, Andrei Tarkovsky, Alice Rohrwacher, Julia Ducournau. My filmic language was strongly influenced by singular gems such as The Night of the Hunter (1955) or The Swimmer (1968). I’m also inspired by the storytelling of anime, from classics like Evangelion or Berserk, to ongoing productions such as Made in Abyss or Ranking of Kings.

e-flux: You recently premiered a performance titled The Talking Car (2023) that, as I understand from the documentation, also incorporates cinematic elements, with footage projected on a screen playing an integral role in the performance. Could you tell us about the piece and its place in your body of work?

AP: The Talking Car was commissioned by the BoCA Biennale in Lisbon and is now touring theaters in Europe. Throughout the play, the characters are in a vehicle speeding in an unknown direction, exchanging dialogue with the car and with the Futurebaby, a large, digital puppet animated by an actress in real time via face-tracking technology. It is a tragicomedy. I find it quite funny and very depressing. The stage videos you mention, animated by my sister Ewa Polska, serve as a background to the actual car on the stage—one might be reminded of the back-projections of moving roads commonly used for car scenes in early cinema.

My work for the theater extends my investigations of complex systems combining human and non-human agents with socio-technological infrastructures. It’s been a joyful experience to spend so much time with the actors, and a lesson in accepting the unpredictability of live performance.

e-flux: Do you envision a future where the boundaries between theater, cinema, and other visual arts will blur, making the distinction between these art forms less significant?

AP: I think that on the level of content, these boundaries don’t really exist anymore. It’s only the distribution that creates distinctions. I often fantasize about finding a production format that could incorporate the best of both worlds: freedom of artistic expression and ease of funding visual arts; respect for workers and financial transparency of cinematic film. This statement might come as a surprise knowing how badly collaborators can be treated in film, but it’s so much worse in art, where even socially engaged projects rarely credit or sufficiently pay their workers.

But right now, the distribution models seem to be completely incompatible, excluding any possibility of blurring the production boundaries. The cinema industry can’t understand how films can be sold in editions and belong to five individuals or institutions in the world; the art industry can’t understand how films can be restricted for release in limited territories and not belong to the artist. And thinking soberly, how can you believe in the sanity of any of these models?

e-flux: Might you reveal what you are currently working on?

AP: At the moment, I’m working on a short public-space film for the opening of a new venue of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw; I’m re-writing The Talking Car to create a film out of it; and I’m seeking partners to produce my script for a science-fiction period drama about telegraph-line workers in Australia.

See Agnieszka Polska, "Future Paracosms and Their Infrastructures," e-flux Notes, March 7, 2023, e-flux.com/notes/525658/future-paracosms-and-their-infrastructures.