Still from Pedro Pinho, O Riso e a Faca (2025).

When Images Are Not Seen Anymore

Is a film festival still a place where we can ask ourselves: What is an image? What does it mean to see? What kind of experience of vision are we having in this historical moment, at this political conjuncture, in the communities where we live?

Vision, as we know, is a complex experience that combines subjective and objective dimensions. At times, it manages to interrogate—often profoundly—the subject who watches. On the screen, our most intimate fantasies can appear; that is, our internal unconscious formations can come back to us in hallucinatory form from the outside. This is what Lacan meant by “the gaze”: a point of intersection where inside and outside—but also subjective and objective, active and passive, real and imagined—blend into one another until they become indistinguishable.

There was a time when cinema was a space—and an experience—where these questions were asked, or at least addressed. And festivals were occasions in which an interrogation of the image could take place. For Freud, dreams were never about the pure experience of them, but rather about the process of translating them into language during analysis. Likewise, film criticism—in all its forms, from film journals to cineclubs—has for decades served as a way to produce discourses around the experience of the image. It does not paraphrase, explain, or worse, rate films with stars or reductive verdicts, as is common today; rather, film criticism is a way to do something with the words that emerge from the enigmatic experience of questioning and analyzing images.

Nowadays one has the impression that festivals are no longer capable of producing critical discourse around the act of viewing images. At best, they serve as platforms to organize or facilitate an event. We’ve become accustomed to seeing festivals, including Cannes, in the hands of producers—what we might call, paraphrasing Marx, the “collective producer”—intent on promoting their films within the increasingly aggressive geopolitics of entertainment capital.

Films and their owners have carved out and consolidated a market niche, small yet globalized: the so-called “festival film,” with its loyal fanbase. Cannes now represents a market segment with its own production companies, its own distribution channels, even its own dedicated arthouse theaters (we all know what they look like: from New York’s IFC Center and Lincoln Center to Milan’s Anteo—every midsized city in the Western world has one). More recently, streaming services like MUBI and the Criterion Channel, where these films often land after theatrical release, have emerged as part of this market segment. Of course, distinctions remain: American entertainment capital, driven by Sundance and tech companies, is more tightly interwoven with platform capitalism, while French protectionism still reserves a role for exhibitor associations and state funding. But the relationship between images and the discourses surrounding them is becoming increasingly homogenous, no matter where you go.

It’s an illusion to think that festivals “freely” select their films. The process often runs in the opposite direction: it’s the films that make the festivals possible—films seeking visibility and a share of our increasingly scarce and fragmented attention (TikTok and Instagram have largely replaced the time once devoted to watching films). We are not far from what Marx wrote about commodities: they require a “shop window” to be displayed in the marketplace and transformed into money—into value. This is not about assigning blame (What came first, the festival or the audience? The producer or the filmmaker?). Rather, we are confronting a system of interlocking relations that reinforce one another. We need to think ecologically, in terms of an environment, or a structure of the symbolic visual. There are no visionary films stuck at the gates of distribution, waiting to reach an eager public, just as there are no experimental filmmakers denied access to capital. There is no virtuous audience and evil system. High and low feed off one another, often reinforcing one another.

As Julien Rejl, artistic director of the Quinzaine des Cinéastes festival, candidly noted in an insightful interview with Senses of Cinema last year:

[Today,] the subject of the film is widely regarded as its most critical feature. To put it differently, nowadays arthouse cinema is primarily concerned with a reflection on the state of the world or society, and it is encouraged to focus on a specific country, its problems, issues, and crises. But we no longer see the emergence of very strong aesthetics, new forceful cinematic proposals, or filmmakers willing to discuss cinephilia.1

The “festival film”—and the symbolic, industrial, and journalistic ecosystem that supports it—is increasingly centered on content: the “What is it about?” And we might ask what this tells us about a society that has delegated its desire for transformation to entertainment. Even remaining within the realm of aesthetics, the problem is that cinema today tends to focus more and more on objects of reality, as if the image were nothing more than an objective window onto the world, to be filled with “stories” and “content,” the two catch-all terms of contemporary aesthetics.

Gone are the days when a film’s political nature was defined by its gaze, or its form, regardless of subject matter, and sometimes despite the director’s politics. This is why filmmakers like Bresson, Bergman, and Tarkovsky were once embraced by the political left, just as Resnais’s Last Year at Marienbad or John Ford’s The Searchers could become leftist reference points.

Perhaps what has changed is not only the discourse surrounding images, but the image itself. It no longer presents itself to the viewer as an enigma or an oracle, something to be questioned or interpreted. The image has become an extension of our narcissism. It no longer asks questions, but provides solutions. Images have become operational, as Harun Farocki once put it: they perform actions; they are not there to be watched.2 Above all, they affirm our identity and reinforce our power. Rather than dividing us, as questions of unconscious desire do, they confirm and unify. They reassure. Indeed, rather than looking and being looked at, today’s images process data of all kinds, even nonvisual data, to produce a “visualization,” as Ruggero Eugeni has explained in his Algorithmic Capital.3 Despite all the clichés about the “society of the image,” we may in fact be entering an era in which images no longer even desire to be seen. Perhaps the very experience of vision, as we knew it in modernity, is fading away.

Acinema 2025

In “Acinema,” Jean-François Lyotard theorized the existence of an anti-narrative, anti-spectacular form of cinema capable of interrupting the logic of representation, a logic that seeks to subordinate the image to the illustrative demands of staging a text.4 The visual register has to resist the temptation to become merely a tool for translating language into images; this was also a central concern for Godard. The problem with this position, however, is that in cinema the image itself is almost inevitably structured like a language, because it takes the form of an “articulation of images,” akin to linguistic syntax. If image A is followed by image B—as must happen to create the illusion of movement within a sequence—it becomes impossible for the second image not to function, at least minimally, as an interpretation of the first. That is, the second image inevitably reveals something of the first, and not something else: it selects certain signifying elements within image A at the expense of others. In cinema, the visual is always irresistibly drawn toward meaning and signification. To produce a rupture, rather than a surplus of meaning, something in this chain of interpretations and significations must be arrested.

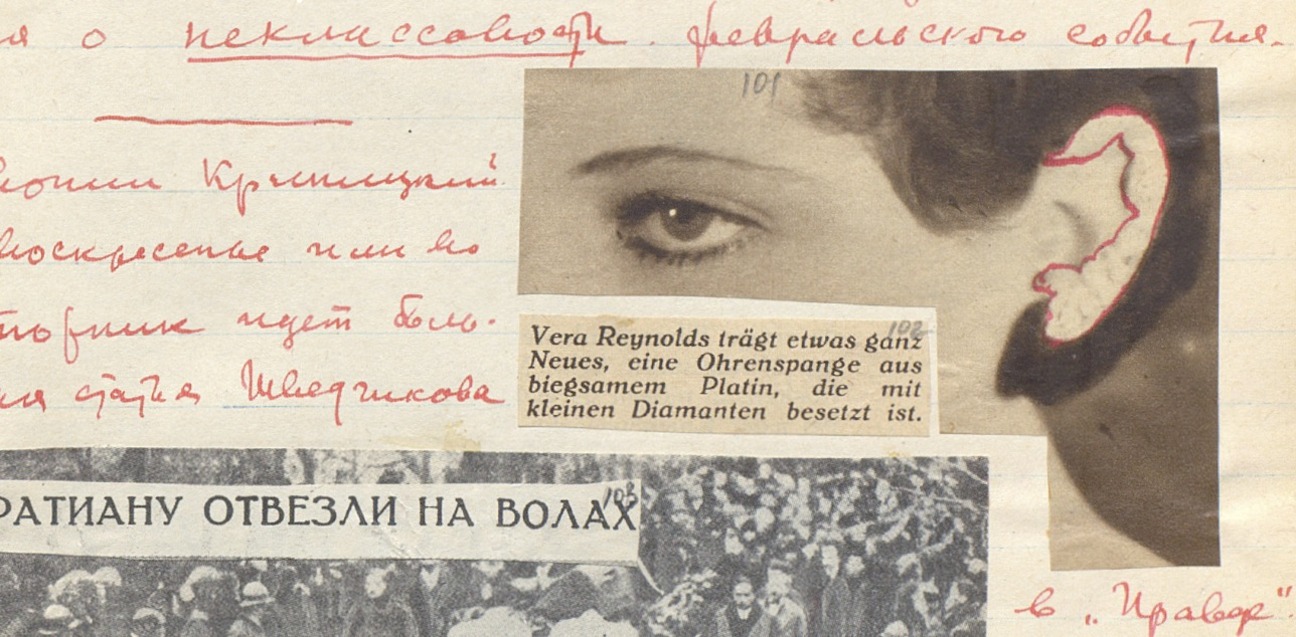

This is why Lyotard realized that a cinema seeking to resist subordination to language cannot but be haunted by a return to the photographic. It is photography—or what Godard described as the pictorial dimension of the image—that cuts the chain of signifiers and replaces the continuity of meaning with the discontinuity of difference.

In Sound of Falling by Mascha Schilinski (competition)—perhaps the biggest surprise of the early days of Cannes this year—we see a girl named Alma looking at a photograph during what appears to be the dawn of the twentieth century. She asks her sister, “But doesn’t she look like Mom?” “No, Alma, that is Mom.” “And the girl below, in her arms—who is she?” “That’s Alma,” the sister replies. We soon learn that Alma was born shortly after the death of a sister who shared her name. In accordance with the custom of the time, the deceased sister’s name was passed on to the newborn. In the photograph, then, Alma sees not only the phantasmatic double of her mother—does that figure resemble her mother, or is she her mother?—but also a phantasmatic double of herself, imagined as dead. Indeed, according to a rather macabre tradition, Alma’s family regularly takes photographs with the dead, posing them as if they were still alive. It is a kind of redoubling of the photographic, not only in the form of the image (life arrested, or death frozen in the guise of eternity) but also in the quasi-embalming of the deceased, as if they continued to live. As Lyotard suggested, the photographic not only disrupts the syntactic articulation of images and the link between the visual and signification; it also introduces the dimension of the phantasmatic, a pretemporal condition in which past, present, and future blur into one another.

Indeed, Sound of Falling is a film in which four temporal axes—the early twentieth century, the immediate period after the Second World War, the late-1970s GDR, and reunified contemporary Germany—echo across one another through four female characters (Alma, Erika, Angelika, and Lenka) and a single geographic location: a farmhouse in the Altmark countryside along the Elbe River (near what would become the East-West border). The film does not follow a vertical narrative structure in which connections between stories unfold linearly (even though some characters appear in multiple timelines); instead, it unfolds elliptically and—here the term is fitting—rhizomatically. What recurs are certain signifiers, such as the phrase “living a life in vain,” and certain gestures, such as Alma’s great-grandmother pinching her hand, which connects spiritually, decades later, to the eel bites that prevent Angelika’s mother from swimming across the Iron Curtain at a pivotal moment in her life.

If Sound of Falling is about memory—and how could it not be, since it spans more than a century—it is not a symbolic or mental memory, but a corporeal and real one. Or rather, a phantasmatic memory, as the film freely shifts between empirically verifiable events—some even historical, like the forced recruitment of soldiers during World War I—and entirely imagined ones that nonetheless appear, paradoxically, even more real. This is no contradiction: in the film, the body is an eminently phantasmatic space. Consider the opening sequence, where Erika, a quiet young girl, pretends to be mutilated. She ties one leg to the other and walks with crutches, attempting to experience what her uncle—who had been deliberately crippled by his parents to avoid conscription—must have felt. The film shows how the pain of that missing limb persists even in its absence, as if the suffering of the body exists not in empirical or biological time, but in a phantasmatic temporality.

Mascha Schilinski, whose debut Dark Blue Girl screened at Berlin in 2017, demonstrates in this second feature not just that she’s found the “right story,” but that she commands a distinctive cinematic language—one shaped not only by her interest in the phantasmatic, but by camera perspectives mediated through obstructions, peepholes, and internal framings that produce a denaturalizing and distancing effect. Sound of Falling, ultimately, is a feminist film—not merely in its subject (the fates of several women over multiple decades, connected yet ultimately isolated), but above all through its phantasmatic language. In this sense, it offers an alternative to the dominant model of militant feminist cinema of recent years—films like Titane and The Substance—by restoring the formal-linguistic dimension to the center of cinematic inquiry. After all, those who have no part in society (something that is true both of sexual difference as well as class antagonism) can only appear as ghosts—that is, as existences yet to come. Which may well be the most essential register of cinema itself.

The other cri de cœur of the early days of Cannes was O Riso e a Faca (literally “The Laughter and the Knife,” though its international title is the equally striking I Only Rest in the Storm) by Portuguese director Pedro Pinho, which screened in the Un Certain Regard section. It’s Pinho’s sophomore fiction feature (he has made several documentaries and shorts), following A Fábrica de Nada, which impressed many at the 2017 Quinzaine des Réalisateurs as one of the most compelling representations of the 2008 economic crisis.

This time, Pinho turns his attention to the contemporary neocolonial condition of an African country—implied to be Guinea-Bissau—seen through the eyes of an outsider: a Portuguese engineer tasked with conducting an environmental impact assessment for a major infrastructure project commissioned by a Brazilian-Chinese multinational. The project, a highway, is set to divide the country in two, connecting the coastal desert to the inland jungle. Yet the protagonist is no typical colonizer, convinced of Western developmental superiority. Rather, he is a leftist, semi-hippie type who wants to “do things right,” show respect for local communities, and critically assess the consequences of European NGO involvement. Sérgio—both the character and the actor, Sérgio Coragem—is portrayed as an anti-establishment figure: he arrives in Guinea-Bissau by car after a long road trip from Portugal and seeks, from the outset, an open, engaged relationship with the local population. At a party, he meets two charismatic locals: the young woman Diara (Cleo Diára) and the queer Gui (Jonathan Guilherme), with whom he enters into a long, tentative game of seduction. Yet the trust they offer him remains partial.

We soon discover that Sérgio’s predecessor—an Italian who had a relationship with a local woman—vanished under mysterious circumstances, and that various players, both international and from the emergent local bourgeoisie, are eager for Sérgio’s report to be completed swiftly and favorably, granting the corporation full freedom to proceed. Sérgio finds himself torn between his vague humanitarian ideals and the internal divisions of Guinean society: while urban youth support the engineering project, the elderly and subsistence farmers in rural areas resist it.

What kind of figure is Sérgio? A well-meaning man caught between forces larger than himself? A hypocrite masking his neocolonialism with ethical posturing? Someone who exoticizes the African country he now inhabits? While Pinho, as in A Fábrica de Nada, skillfully blends polyphonic registers and essayistic inserts (such as the striking moment when a young Guinean nouveau riche explains “primitive accumulation” to Sérgio in a bar), this time the truth is not voiced by Marx but Freud. That is, the truth lies not in what Sérgio says when he works, but what he does in the bedroom—from a remarkable conversation with a sex worker in a brothel (whom he, as a white “ethical” man, wants to save, only to be angrily answered with a monologue on the sexual politics of white neocolonialism) to his seduction attempts toward Diara (and also Gui), who first rebuffs him, then partially reciprocates, ultimately forcing him into a cuckold/voyeuristic position during her sexual encounter with another man.

As Sérgio agonizes over the ethical weight of his complicity in the web of economic and political interests—his subjective position is that of a neurotic, unable to act—politics in the film manifests, above all, as sexual politics, where the truth of desire emerges in all its clarity. In the swirl of parties frequented by NGO expats and the rising local bourgeoisie, Sérgio enters a spiral of ever more transgressive practices of enjoyment, succumbing to his own paralysis. From this, his exclusion from the local network of interests becomes painfully apparent. As if to say: Euro-Chinese neocolonialism can force African nations into an externally imposed and ecologically ruinous path of development, but it can never compel them to ultimately desire it.

Maria Giovanna Vagenas, “Groundbreaking Cinephilia: A Conversation with Julien Rejl, Artistic Director of the Directors’ Fortnight,” Senses of Cinema, no. 107 (November 2023) →.

Harun Farocki, “Phantom Images,” Public, no. 29 (2004).

Ruggero Eugeni, Il capitale algoritmico (Morcelliana, 2021).

Jean-François Lyotard, “Acinema,” in Acinemas: Lyotard’s Philosophy of Film, ed. Graham Jones and Ashley Woodward (Edinburgh University Press, 2017).